Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Moses Mendelssohn’s Be’ur: Translating the Torah in the Age of Enlightenment

A picture of Moses Mendelssohn displayed in the Jewish Museum, Berlin, based on an oil portrait (1771) by Anton Graff in the collection of the University of Leipzig. Wikimedia

Moses Mendelssohn – Background

Moses Mendelssohn (1729-1786) was an exceptional figure in the eighteenth-century: a leading philosopher of the German Enlightenment who was also an observant Jew. He not only compartmentalized these two identities, but argued that “eternal truths,” accessible to all through reason, were compatible with revealed, historical Judaism. Mendelssohn was raised in Dessau, a small city (now called Dessau-Roßlau) between Leipzig and Berlin, where traditional Jewish learning, combined with exposure to new ideas and publications (such as a new printing in 1742 of Maimonides’s Guide to the Perplexed), laid the foundation for his future career and outlook.

After moving to Berlin, in addition to philosophy and work in the textile industry, he became a literary critic and translator, fully engaged in the cultural trends of his day: the “poet laureate of the Berlin Jewish community.”[1] Mendelssohn turned to Bible translation after 1770, claiming that poor health prevented him from philosophical mediation.

That Mendelssohn began translating Psalms and biblical poetry is not surprising; to engage with poetry was the mark of a German intellectual. But this new translation of the Pentateuch, in his words, would also be a “service” to his children and his nation in many respects: it would provide an alternative to Christian Bibles and the older Yiddish translations, and at the same time, advance the cultural education, the Bildung, of Ashkenazi Jews.[2]

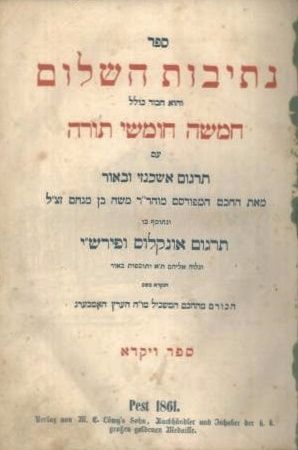

Be’ur

He gave this Pentateuch translation an evocative title, “The Paths to Peace” “Netivot Hashalom,” alluding to a biblical text (Proverbs 3:17) and the liturgy of the Torah service. But it is mainly known by the (prosaic) name Be’ur (“Explanation”), after the explanatory Hebrew commentary that appeared on each page. In keeping with his aesthetic agenda, Mendelssohn highlighted poetic passages in the Pentateuch, such as the Song of the Sea (Exod 15), by including long excurses in the commentary about the poetry.

He gave this Pentateuch translation an evocative title, “The Paths to Peace” “Netivot Hashalom,” alluding to a biblical text (Proverbs 3:17) and the liturgy of the Torah service. But it is mainly known by the (prosaic) name Be’ur (“Explanation”), after the explanatory Hebrew commentary that appeared on each page. In keeping with his aesthetic agenda, Mendelssohn highlighted poetic passages in the Pentateuch, such as the Song of the Sea (Exod 15), by including long excurses in the commentary about the poetry.

To counter-balance these and other innovations, Mendelssohn, in his long introduction, constructed a religious genealogy for his project, invoking Moses, Ezra, the Aramaic Translations (Targumim), the Rabbis, Saadia Gaon, the Masoretes, Maimonides, Elija Levita, and many others. By implication, the modern translator joined those charged with the sacred task of transmitting, explaining, and thereby safeguarding, the Torah.

Features and Style

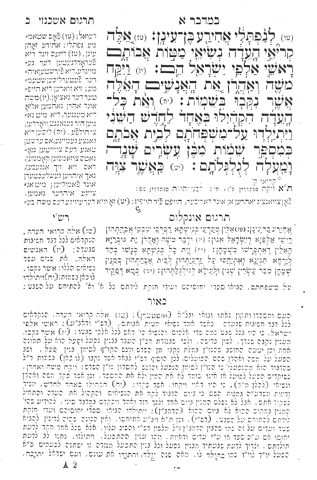

The original page layout, with its four quadrants and all-Hebrew appearance, bore a striking resemblance to the layout of the Miqra’ot Gedolot or Rabbinic Bible. Not only did theBe’ur include Hebrew scripture, it situated the German translation (called Targum Ashkenazi) in the place normally reserved for the Aramaic Targum, as if to co-opt the legitimacy of a venerated ancient translation that had long since become a hermeneutic tool.

Mendelssohn wrote in a style called Jüdisch-deutsch, in which German was transcribed in Hebrew letters. This was a common strategy of maskilim, the representatives of the Jewish Enlightenment, writing for Yiddish-speaking Jews in this transitional period. (Even so, Mendelssohn’s German was too difficult for the average German Jew.)

Mendelssohn inserted question marks and exclamation points into the translation where appropriate, but he also followed the syntax of the cantillation marks, inserting backslashes for softer breaks and colons to mark a pause (etnachta) and end of verse (sof passuq). These latter marks were not imported into the later editions printed in Gothic letters, but they teach us something important about his original intent and method.

The bottom half of the page included commentary (Be’ur) most of which was not composed by Mendelssohn himself, as well as Tikkun Sofrim (Scribal Corrections)[3]For the first time, commentary was designed to explain the decisions of the translator, in particular, where peshat, the simple meaning, diverged from a traditional interpretation. The inclusion of this commentary—as we shall see below—testifies to Mendelssohn’s use of translation to explain the “ways of language,” of both German and Hebrew—the new “paths” to Torah for modern Jews.[4]

The bottom half of the page included commentary (Be’ur) most of which was not composed by Mendelssohn himself, as well as Tikkun Sofrim (Scribal Corrections)[3]For the first time, commentary was designed to explain the decisions of the translator, in particular, where peshat, the simple meaning, diverged from a traditional interpretation. The inclusion of this commentary—as we shall see below—testifies to Mendelssohn’s use of translation to explain the “ways of language,” of both German and Hebrew—the new “paths” to Torah for modern Jews.[4]

Each of these features sought to communicate to Rabbis and traditional Jews that a translation that included German in its pages could remain an authentic, Jewish Bible.

More than Just a Translation

Mendelssohn wanted his translation to be clear, correct, and beautiful. His first priority as a translator was to disambiguate scripture. To this end, he inserted conjunctions and transitional phrases wherever possible and did not hesitate to insert parentheses into the body of the translation.

When did Amram and Yocheved Marry?

A classic example is the opening of Moses’ birth story: “A certain man of the house of Levi went and married a Levite woman” (Exodus 2:1, JPS). Mendelssohn added three words to the beginning of that verse, “Vor einiger Zeit” “some time before.” (He probably borrowed this phrase from the Wertheim Bible (1735) translated by Johann Lorenz Schmidt.[5]) The addition not only lent this important pericope a proper beginning, it clarified the sequence of events, solving a notorious chronological confusion about the marriage of Moses’ parents: if they got married when baby boys were already being thrown into the Nile, why did they not have to hide Aaron, who is the older brother?

The midrash solves this problem by suggesting that the parents had split up and that this verse refers to their remarriage (b.Sotah 12a), but Mendelssohn’s gloss suggests that this marriage actually happened before the decree. He expands on this point in his commentary:

ועל דרך הפשט אין מוקדם ומאוחר בפרשה, כי היה זה קודם גזרת פרעה, וילדה מרים ואהרן, ואחר כן גזר פרעה לאמר כל הבן הילוד היאורה תשליכהו, ותלד הבן הטוב הזה, וכן מתורגם בל”א.

According to the peshat (simple meaning), the order of events in the parasha is not definitive, for this occurred before Pharaoh’s decree, and Miriam and Aaron were born [before the decree], and afterwards, Pharaoh decreed (Exod 1:22): “Every boy that is born you shall throw into the Nile,” and then this beautiful boy was born. This is also the way it was rendered in the German.

The Meaning of “I am not a Man of Words”

When Moses tries to beg off the mission at the burning bush (Exod 4:10), claiming “I am not a man of words,” Mendelssohn first translated literally, “Ich bin kein Mann von Worten” and then added, in parentheses, “das heißt kein guter Redner,” “which means, not a good speaker.”

Variety and High Language

Rather than repeat the same German word for a given Hebrew word whenever it appeared (as in Buber and Rosenzweig’s Leitwort method),[6] Mendelssohn varied vocabulary and preferred fancy words to plain. According to Exod 2:2, Moses’ mother saw that he was tov, rendered by others as “fine,” “good,” or “beautiful” (JPS). Mendelssohn chose “wohlgebildet” (well-formed), reflecting his penchant for multisyllabic words and high diction. Perhaps the alternate meaning of gebildet, civilized or well-educated, also appealed to him.

Another creative touch was to refer to Pharaoh’s daughter as a Prinzessin (Exod 2:5), “princess,” and her maidens as Kammermägde, “chambermaids.” And in a most dramatic vein, he rendered the phrase כי גאה גאה in the Song of the Sea (Exod 15:1)—usually rendered “for he has triumphed gloriously”—as “der hoch erhaben sich zeigt,” “who shows himself highly sublime,” thereby introducing the philosophical concept of sublimity into the Hebrew Bible. These examples reveal that translation could not only clarify, but could also enhance and “improve” the biblical text.

Translating YHWH – The Eternal Being (Der Ewige)

Mendelssohn’s boldest theological move was to paraphrase Exod 3:14: אהיה אשר אהיה (eheye asher eheye) as “Ich bin das Wesen, welches ewig ist,” “I am the Being which is eternal,” and on that basis, to render YHWH, the Tetragrammaton as “Der Ewige,” “The Eternal One.”[7] He justified his choice by way of an amalgam of rabbinic sources and philosophical principles—an explanation later critiqued by Franz Rosenzweig.

Mendelssohn believed that every word in the Torah could and should be clearly translated, and as a philosopher, there was no way he would not take up the ultimate challenge of identifying the essence of the biblical God. Der Ewige had a long afterlife in subsequent German Jewish Bibles and in the siddur.

Commentary: Explanation and Experimentation

Mendelssohn insisted that the published translation include an explanatory commentary. The commentary was a collaborative project, with individual books authored by Mendelssohn’s disciples, the most prominent of whom was Solomon Dubno (though Mendelssohn did write the commentary for the first six chapters of Genesis and most of Exodus). The commentary contains information, grammar lessons, translator’s notes, and a running dialogue with prior exegetes and translators.

Discourse on the Calendar

The passage explaining the simple word “Monat” (month; Exod. 12:2) exemplifies the ways in which the Bible in the Haskalah functioned as a lexicon or textbook, providing Jewish readers with information external to scripture itself.[8]Here, Mendelssohn sees the verse as a pedagogical opportunity to explain the calendar:

החדש – זמן סבוב הלבנה מחדושה כ”ט יום י”ב שעות ותשצ”ג חלקי שעה. קרא חדש ימים או חדש, היום הראשון ממנו יקרא ראש חדש או חודש לבדו, יאמר “חדש ושבת” (ישעיה א:יג) חדשיכם (שם יד). והטעם יום חדוש אור הלבנה.

This month: The time period of the rotation of the moon from renewal to renewal is 29 days 12 hours and 793 parts of an hour.[9] It is called month or month of days, and the first day is called “head of month” or simply “month,” as in “month and Sabbath” (Isa 1:13) or “your months” (ibid v. 14). And the reason is because it is the day in which the light of the moon is renewed.

וזמן תקופת השמש מנקודה אחת בגלגלו עד שובו שנית אל הנקודה ההיא יקרא שנה, ובשנה פעמים שנים עשר חדשי הלבנה ובפעמים שלשה עשר כידוע, כי שנת החמה שס”ה יום וקרוב מרביעית היום.

And the period of time the sun requires from one point in its cycle to its return to the same point is called a year, in a year there are sometimes twelve lunar months and sometimes thirteen, as is known, because the solar year is 365 and almost a quarter days.[10]

Sarah Laughed to Herself

Genesis 18:12 relates that when the matriarch Sarah heard the announcement that she would bear a son at the age of ninety-nine, she “laughed in her heart,” to herself. Mendelssohn’s “da lachte Sarah in ihrem Herzen,” seems straightforward, both accurately reflecting the Hebrew בקרבה and following traditional interpretation (see, e.g., Targum Yerushalmi and Pseudo-Jonathan, ibn Ezra, Radak, Ralbag, etc.). Dubno’s comment begins as if it were an entry in a thesaurus:

והנה לשון צחק יתבאר על ה’ ענינים (ספיעלאן, ספאטטען, לאכען, שימפפען, פרייען) וכן אחד יובן מענינו.

The language of tzachak (laughed) can be explained in five ways (spielen, spotten, lachen, schimpfen, freuen) [=playing, mocking, laughing, insulting, being joyful], and each one is understood from the context.

But the Be’ur proceeds to explain why laughter in one’s mind should still be considered mockery and to explain why this is different than Abraham’s laughter about the same message for the same reason in Gen. 17:17.[11] Thus, the commentary works both to defend the traditional explanation of why Sarah’s laughter, but not Abraham’s, was a form of mockery, while at the same time explaining why the translator did not render Sarah’s laughter with the German word for mockery, but stuck with “in her heart.”

Peshat over Derash

Mendelssohn consulted the full range of commentaries, as well as Yiddish translations, the Luther Bible, as well as other modern German translations. He firmly resisted the historical-critical approaches of his Christian contemporaries such as Johann David Michaelis. But in his Preface, he emphasized one choice above all: whether to translate according to peshat orderash—the simple meaning or the exegetical, Jewish rendering—in cases where the two conflicted:

Everywhere where the ways of peshat and derash parted from one another and varied, I chose in my translation sometimes only the peshat, at other times only the drash, and he [Dubno] explained in his Be’ur why I proceeded that way.[12]

Here, Mendelssohn portrays the modern Jewish Bible translator as akin to a pious exegete, while emphasizing his competency to make difficult translational decisions. Scholars note that modern translators typically gave voice to ambivalence. It was not “methodological wavering,” but an awareness of the “fundamental aporias that structure translation,” in other words, the difficulties inherent to the task of translation.[13]

The Be’ur in Context

Moses Mendelssohn’s approach to translation was motivated by religious needs and cultural desiderata, and by developments internal and external to Jewish society. In the eighteenth century, Jews throughout Western and Central Europe began to reclaim the Hebrew Bible. Ashkenazi Jews had lost access to the Bible in Hebrew; the Torah they studied was mediated by rabbinic commentary and accessed mainly by way of Talmud, or in the case of young children, through repetition or memorization of selected verses. The hope was that engaging with the Hebrew Bible —through scholarship, sermons, visual art, literature, as well as translation—would make it possible for Jews to remain Jews as they entered society at large.

This was also the age of the Christian “Enlightenment Bible,” invented in Germany in the 18th century, which portrayed scripture as “divinely inspired culture” instead of the literal word of God.[14] Mendelssohn modeled his efforts on the Christian translations of Pietism and the Enlightenment such as the Wertheim Bible (1735) and the thirteen-volume translation of Johann David Michaelis[15] (1769-85), which updated the Luther Bible, replacing its “slavish” Hebraisms with a conceptual, scholarly and literary German idiom.

Furthermore, many German intellectuals practiced and theorized about translation; they valued translation philosophically, as a cultural practice that, since Luther, had been constitutive of language and national identity.

Yiddish Precedents for Mendelssohn’s Translation

But Mendelssohn was not the first to produce a modern Jewish Bible translation with a cultural agenda. The credit goes to two Yiddish translators, Jekutiel Blitz and Joseph Witzenhausen, and their publishers, in Amsterdam in the 1670s. The production of these two complete Hebrew Bibles in Yiddish was inspired by the popularity of the Dutch States Bible (1637)—the first Dutch translation from the original languages of scripture–as well as by the growing dissatisfaction with the Old Yiddish Bibles. By the seventeenth century, as Marion Aptroot explains, the Old Yiddish Bibles were no longer adequate, in part because the Yiddish translation vocabulary, chumesh taytsch, had become “not only archaic, but incomprehensible.”[16]

Mendelssohn criticized the language of Blitz’s translation in his Preface; this teaches us that it was still in circulation. The Blitz and Witzenhausen translations, which also claimed to be “clear, correct, and beautiful,” provided a prototype of a modern Jewish vernacular Bible, which Mendelssohn sought to modernize (linguistically) and also traditionalize (through the inclusion of Hebrew scripture, commentary, and Scribal Corrections.)

The Translation Revolution

The most radical feature of the Be’ur, and of the two Amsterdam Yiddish Bibles produced one century earlier, is one that we might not even consider noteworthy: the creation of a one-to-one rendering of the source text in stylistically and syntactically correct prose. Such a work was unprecedented in a society which relied on vernacular Bibles such as the narrative Bible Tsene Rene, or glossaries such as Mirkeves Hamishna, neither of which looked anything like a modern translation. Ancient prohibitions against writing a one-to-one rendering of the Torah (other than the Aramaic Targum Onkelos) had endured into the medieval period. [17]

Influences and Controversies

Mendelssohn’s Pentateuch translation was reprinted numerous times in Germany, since Jews rapidly learned German. In nineteenth-century Eastern Europe it was also widely used in schools set up by the maskilim and also in traditional schools. As a sign of its transitional character, later editions went in two opposing directions: some “secularized” the Be’ur by printing the translation in Gothic and Latin script, removing Hebrew scripture, commentary, and Scribal Corrections, and adding a German-language commentary; others designed a more traditional version by restoring both Rashi and the Aramaic Targum onto the page.

After his death, Mendelssohn’s followers, called “biurists,” applied his method to the other biblical books, creating a new corpus of translations.[18] So great was the impact of this translation that leading Rabbis and scholars of each subsequent generation—Zunz, Philippson, Hirsch, Buber and Rosenzweig and many others—vied to become the “next Mendelssohn” and produce a monumental translation for their time; these too must be counted among Mendelssohn’s legacies.

Among the orthodox Rabbis, Mendelssohn’s Bible was controversial. Samson Raphael Hirsch sharply criticized his use of “The Eternal One” for God, which to him represented the failure of the Haskalah as a whole. A recent article exploring the reception of Mendelssohn among Orthodox Jewish rabbis laments the failure of both ideological Jewish movements to appreciate Mendelssohn’s exemplary contributions:

The earnest Reform Jew found him far too halakhic. The Orthodox had more in common, but steered clear of his loaded legacy. Moses Mendelssohn was off-limits, despite his religious observance and noble efforts to engage Judaism with the modern world.[19]

Mendelssohn is most famous today among scholars of philosophy. The Be’ur is often simplistically referred to as a mere “passport” to the German language, although Mendelssohn’s Hebrew writings and cultural contributions have begun to receive more attention in recent years.

Reclaiming the Bible

In the end, Mendelssohn’s accomplishment as a translator went beyond the three motives he himself expressed: linguistic; pedagogical; cultural. He completed a religious-cultural project in the truest sense, connecting Torah (understood as the core set of Jewish norms, Jewish outlook, Jewish everything) with the language of the Hebrew Bible.

Mendelssohn’s translation, and those of his successors, sought to reclaim and elevate the status of the Hebrew Bible—not only to enable Jews to retain their connection to the Torah as they entered modern society, but also to showcase the Hebrew Bible as a great work of Jewish literature and, indeed, world literature.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

January 24, 2017

|

Last Updated

March 13, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Abigail Gillman is Associate Professor of Hebrew, German and Comparative Literature at Boston University and Acting Director of its Elie Wiesel Center for Jewish Studies. She holds a Ph.D. in Germanic Languages and Literature from Harvard and a B.A. in Literature from Yale. She is the author of Viennese Jewish Modernism: Freud, Hofmannsthal, Beer-Hofmann, and Schnitzler, and A History of German Jewish Bible Translation.

Essays on Related Topics: