Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Psalm 104 and Its Parallels in Pharaoh Akhenaten’s Hymn

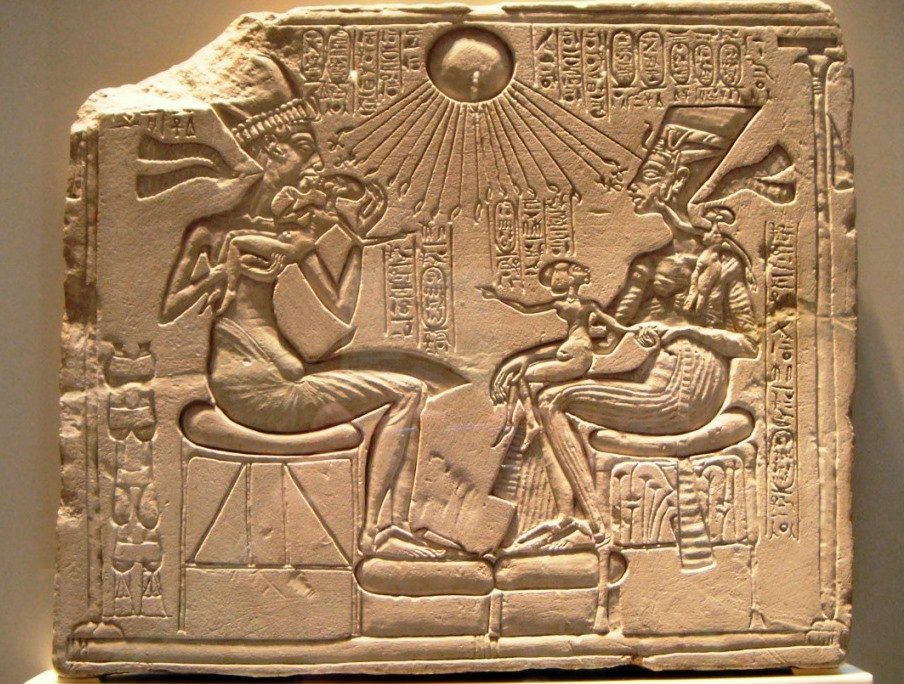

Relief of Akhenaten and Nefertiti praying to Aten, 1372-1355 B.C.E. Wikimedia

Psalm 104, a relatively long psalm of 35 verses, is comprised of five sections:[1]

A. God in Heaven (vv. 1–4)—The opening paragraph describes God in heaven, clothed in glory and majesty and wrapped in a robe of light, spreading the heavens like a tent cloth. God sits upon the clouds, the winds, and the heavenly waters, making the wind and the fiery flames his emissaries. This segues into the creation of the terrestrial world, the theme of the next section.

B. Creation of land and water (vv. 5–9)—God establishes the foundation of the earth and covers much of it with deep water. Unlike Genesis 1, the process is combative: God’s blast and thunder causes the waters, which had been standing over the mountains, to flee, and then God sets boundaries for them, so the water will not again overwhelm the dry land.

C. Life on earth (vv. 10–19)—Using the ocean waters as a segue, the psalm continues with how God makes freshwater spring forth, allowing the animals to drink and the birds to live beside them in the trees (vv. 10–12). The fresh water runs down the mountains, sates the earth, allowing grass to grow for cattle to eat, and agriculture for humans, who produce wine, oil, and bread (vv. 13–15). Trees drink up the water and birds nest within them (vv. 16–17), while wild goats live on mountains and rock-badgers in their crags (v. 18). The section ends with the reference to the sun and moon in the heavens, and how these determine times on earth (v. 19).

These first three sections move from God dwelling in heaven, to God’s creation of the world, separating water and land, providing water to enable life on earth,[2] culminating in humanity. These themes are all known from other places in the Bible.[3] Similarly, the theme of God’s conflict with the primordial sea is an instance of the common ancient Near Eastern trope known as the “war against chaos (Chaoskampf),” found in several passages in the Bible, such as this verse from Psalms:

תהלים עד:יג אַתָּה פוֹרַרְתָּ בְעׇזְּךָ יָם שִׁבַּרְתָּ רָאשֵׁי תַנִּינִים עַל־הַמָּיִם אַתָּה רִצַּצְתָּ רָאשֵׁי לִוְיָתָן תִּתְּנֶנּוּ מַאֲכָל לְעָם לְצִיִּים.

Ps 74:13 It was You who drove back the sea with Your might, who smashed the heads of the monsters in the waters, it was You who crushed the heads of Leviathan, who left him as food for the monsters of the sea.[4]

The sun and moon determining time on earth is also a biblical trope, appearing most famously in chapter 1 of Genesis (v. 14).[5]

D. Night Is Dangerous, Day Is Hopeful (vv. 20-30)

The psalm’s fourth section takes a dynamic look at life on earth not through landscape, but through the variable of time. Following up on the reference to the lunar and solar cycles in the previous verse, it contemplates nighttime as a time for the prowling of dangerous animals:

תהלים קד:כ תָּשֶׁת חֹשֶׁךְ וִיהִי לָיְלָה בּוֹ תִרְמֹשׂ כָּל חַיְתוֹ יָעַר. קד:כא הַכְּפִירִים שֹׁאֲגִים לַטָּרֶף וּלְבַקֵּשׁ מֵאֵל אָכְלָם.

Ps 104:20 You bring on darkness and it is night, when all the beasts of the forest stir. 104:21 The lions roar for prey, seeking their food from God.

While this motif is unusual for the Bible, it has a particularly close parallel in one ancient Egyptian poem called the Great Hymn to the Aten, written by Pharaoh Akhenaten[6] (1353-1336 B.C.E.), the world’s first monotheist.[7] The hymn praises the divine sun disk Aten, the one true God according to Akhenaten’s theology,[8] and as such, describes the perils of the night, when the Aten is absent. Note the hymn’s parallels to the verses in the psalm, down to specific reference to lions:

13–23 When you set in the western lightland, Earth is in darkness in the condition of death. The sleepers are in their chambers, heads covered, one eye does not see the other. Were they robbed of their gods under their heads, they don’t notice it. Every lion comes from its den, all the serpents bite. Darkness is a grave, Earth is in silence: Their creator has set in his lightland.

The parallels between the Psalm and the Hymn, are also evident in the following passages of each. The Psalm next speaks about day as a time of vibrant activity:

תהלים קד:כב תִּזְרַח הַשֶּׁמֶשׁ יֵאָסֵפוּן וְאֶל מְעוֹנֹתָם יִרְבָּצוּן. קד:כג יֵצֵא אָדָם לְפָעֳלוֹ וְלַעֲבֹדָתוֹ עֲדֵי עָרֶב.

Ps 104:22 When the sun rises, they (=the beasts) come home, and couch in their dens. 104:23 The human then goes out to his work, to his labor until evening.

Similarly, the next section of the Aten Hymn speaks about daytime activity, including even a reference to people going to work:

Aten Hymn 24–33 At dawn you have risen in the lightland and are as radiant as the sun disk of daytime. You dispel the dark, you cast your rays, the Two Lands are in festivity daily. Humans awake, they stand on their feet, you have roused them. They wash and dress, their arms in adoration of your appearance. The entire land sets out to work, all beasts browse on their herbs, trees, herbs are sprouting.[9]

Since, in the hymn’s theology, the sun disk is coterminous with the deity, the setting of the sun leaves the world godless, but the rising of the sun the next morning brings the earth back under divine protection.

The American Egyptologist James Henry Breasted (1865–1935), who wrote his dissertation in Germany (and in Latin!) on Pharaoh Akhenaten, drew attention more than a century ago to striking parallels between the Great Hymn and Psalm 104.[10] A close comparison shows that there are (a) a large number of shared motifs (b) in the same order, including (c) some motifs that are not found anywhere else in the Bible. Given that the hymn is earlier than Psalms, this would then be a clear case of borrowing by one of the biblical authors.

Further Parallel Themes

In addition to the shared description of night as a time of danger, and day as a time of activity, the texts share several other themes:

How Many Are Your Deeds!

Following the night-day passage, the Psalmist offers an exclamation of praise:

תהלים קד:כד מָה רַבּוּ מַעֲשֶׂיךָ יְ־הוָה כֻּלָּם בְּחָכְמָה עָשִׂיתָ מָלְאָה הָאָרֶץ קִנְיָנֶךָ.

Ps 104:24 How many are your deeds, O LORD! You have carried them all out with wisdom; the earth is full of Your creations.

We see a very similar praise in the Aten Hymn:

Aten Hymn 63–67 How many are your deeds, though hidden from sight, O Sole God beside whom there is none (nn ky wpw ḥr.f)! You made the earth following your heart when you were alone, with people, herds, and flocks!

Indeed, the Great Hymn goes farther than the psalmist in this passage, in declaring Aten to be the only god in existence.[11]

The Sea

Next the Psalm describes God’s relationship with the sea and its creatures:

תהלים קד:כה זֶה הַיָּם גָּדוֹל וּרְחַב יָדָיִם שָׁם רֶמֶשׂ וְאֵין מִסְפָּר חַיּוֹת קְטַנּוֹת עִם גְּדֹלוֹת. קד:כו שָׁם אֳנִיּוֹת יְהַלֵּכוּן לִוְיָתָן זֶה יָצַרְתָּ לְשַׂחֶק בּוֹ.

Ps 104:25 There is the sea, vast and wide, with its creatures beyond number, living things, small and great. 104:26 There go the ships, and Leviathan that You formed to sport with.

This too parallels the Aten Hymn:

Aten Hymn 39–44 Ships fare north, fare south as well, every road lies open when you rise. The fish in the river dart before you your rays are in the midst of the sea.

Dependent on God

The psalm continues by describing how God’s creations are dependent on God’s presence and support:

תהלים קד:כז כֻּלָּם אֵלֶיךָ יְשַׂבֵּרוּן לָתֵת אָכְלָם בְּעִתּוֹ. קד:כח תִּתֵּן לָהֶם יִלְקֹטוּן תִּפְתַּח יָדְךָ יִשְׂבְּעוּן טוֹב.

Ps 104:27 All of them look to You to give them their food when it is due. 104:28 Give it to them, they gather it up; open Your hand, they are well satisfied;

Here too, the Aten Hymn has a parallel, though referring to people as opposed to animals:

Aten Hymn 72–73 You set every man in his place, you supply his needs; everyone has his food, his lifetime is counted.

God’s Absence is Death, Presence Is Life

The section ends with the theme with which it opened, God’s absence and presence:

תהלים קד:כט תַּסְתִּיר פָּנֶיךָ יִבָּהֵלוּן תֹּסֵף רוּחָם יִגְוָעוּן וְאֶל עֲפָרָם יְשׁוּבוּן. קד:ל תְּשַׁלַּח רוּחֲךָ יִבָּרֵאוּן וּתְחַדֵּשׁ פְּנֵי אֲדָמָה.

Ps 104:29 Hide your face, they are terrified, take away their breath, they perish and turn again into dust; 104:30 send back your breath, they are created, and you renew the face of the earth.

Since the Aten Hymn envisions the sun disc as Aten, this theme appears in the hymn as well:

Aten Hymn 112–113 When you dawn, they live; when you set, they die.

All these parallels lead to the conclusion that Psalm 104 bears the strong imprint of Akhenaten’s hymn.[12] Biblical scholars and traditional readers are often wary of claims of direct borrowing, usually for different reasons. In this case, though, Paul Dion makes the most important comment:

There is simply no alternative explanation for the concentration of contacts between these two poems heaped up in vv. 19-30; the[se] comparisons speak for themselves.[13]

The dependence of the psalm on the Great Hymn explains the emphasis on the blessedness of day as opposed to the frightening nature of night.[14]

The Theology of Akhenaten

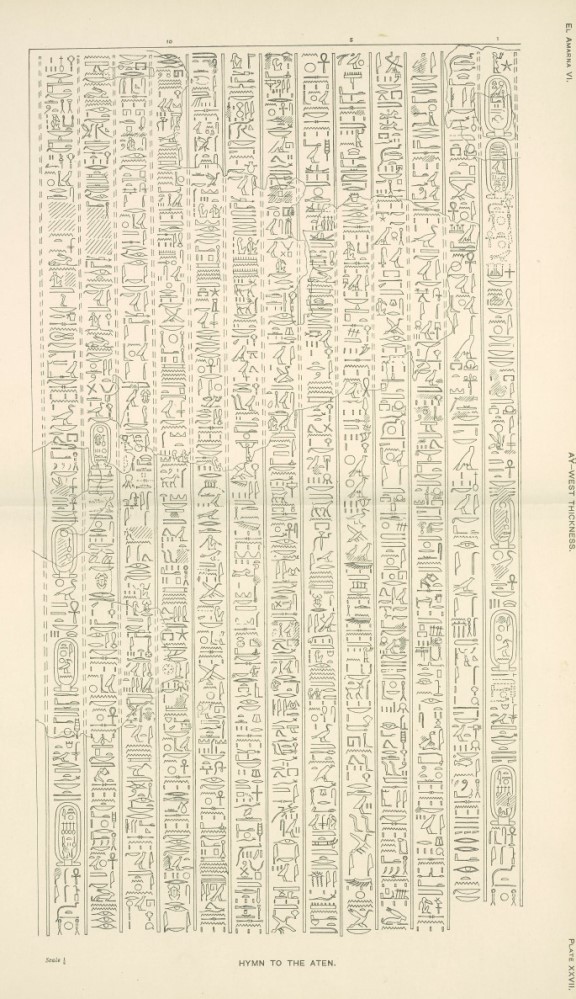

Spread over thirteen columns of hieroglyphic text, the Great Hymn of the Aten was discovered in Amarna, ancient Akhet-Aten “the horizon of Aten,” the new capital founded by Akhenaten, in the tomb of a man named Ay.[15]

|

|

The poem revolves around three large themes: (a) visibility, (b) daily creation, and (c) energy. It tackles first the perennial problem of god’s transcendence and immanence by asserting that although the Aten is far off, its rays reach down and are upon earth. This image is captured visually in the innovative way the Aten is depicted in Amarna art: as having hands reaching down to touch its worshipers – Akhenaten, Nefertiti, and their family.[16]

Akhenaten, Nefertiti and three daughters beneath the Aten, Museum Berlin, Wikimedia

Akhenaten, Nefertiti and three daughters beneath the Aten, Museum Berlin, Wikimedia

Since the sun disk is the one and only God, at sunset, everything falls asleep, and the earth seems dead. This radical notion is not part of traditional Egyptian thought, according to which every night, the sun travels through the duat (underworld), avoiding the attempt of the great serpent Apep to stop him from rising. The sun succeeds in rising the next morning with the help of Osiris, the king of the underworld, who was the god responsible for regeneration and rebirth.

In short, standard ancient Egyptian religion was far from monotheistic. The sun gods—there were more than one of them—were powerful, but not all powerful, and if Ra was busy in the duat at night, there were plenty of other gods to look after the earth at that time. Indeed, Osiris was believed to use his rejuvenating powers at night, allowing the cosmos to recharge for the following day. But for Akhenaten, the absence of Aten meant the total absence of divinity. The forces of life come only from the Aten, and in its absence, the earth was silent and dead.

At the same time, without divine control, the forces of chaos are unleashed – the lions and the serpents – which both exemplify and symbolize the lack of ma‘at (mꜣʿt, justice and order) in the world absent the Aten.[17] At the end of the hymn, Akhenaten will call himself “the king who lives by ma‘at,” and here he shows that without the Aten, no ma‘at is possible.

Indeed, Akhenaten was so radical in his monotheism that he seems to have objected to the word netjer “god” as a category. Egyptian writing normally has signs called “determinatives” or “classifiers” at the end of words, which provide information about the word just written. Normally any god’s name would be followed by the netjer sign the classifier for “god,” but in all inscriptions at Amarna, including the Great Hymn, it is never used, even for the Aten. As the Israeli Egyptologist Orly Goldwasser observed, in Akhenaten’s theology there simply is no category “gods.”[18]

Elsewhere in the Psalm, we may also see glimmer of Akhenaten’s theology:

Humanity

Psalm 104 speaks about people, using universalist terms like אָדָם and אֱנוֹשׁ as opposed to “your people Israel” or some such locution. Akhenaten’s worldview, as expressed in the hymn, is deeply universalist.[19] While Akhenaten does see a unique role for himself, the son of the god, and for his queen Nefertiti (see image above), he does not seem to think that the Aten has a closer relationship with Egypt than with any other people or land:

Aten Hymn 81–91 You made the earth following your heart when you were alone, with people, herds, and flocks, all upon earth that walks on legs, all on high that fly on wings. The foreign lands of Syria and Nubia, the land of Egypt. Everyone has his food, his lifetime is counter. Their tongues differ in speech, their characters likewise, their skins are distinct, for you distinguished the people.

Thus, the hymn and psalm are both universalistic, albeit in different ways.

Water

The psalm references fresh water multiple times, whether pouring down a mountain or coming up from springs. Notably, Akhenaten focuses many lines on water, and, in keeping with his universalist outlook, praises the Aten both for how the Egyptians get water from the Nile (which they believed came from the netherworld), and how other peoples get water from rain (the Nile from the sky, as it were):

Aten Hymn 77–90 You made the Nile in the netherworld, you bring him when you will, to nourish the people, for you made them for yourself. Lord of all, who toils for them, Lord of all lands who shines for them, sun disk of daytime, great in glory! All distant lands, you keep them alive. You made a heavenly Nile descend for them; he makes waves on the mountains like the sea, to drench their fields with what they need. How efficient are your plans, O Lord of eternity! A Nile from heaven for foreign people and for the creatures in the desert that walk on legs, but for Egypt the Nile who comes from the netherworld.

For an Egyptian, it is a remarkable act of divine grace that the Aten created a “heavenly Nile,” a Nile in the sky, to drip down water on the people elsewhere, including those not fortunate enough to have a normal Nile River in the ground.[20]

How Did It Get to Israel?

Immediately after his death, Akhenaten’s ideas were banned, and his city, artistic style, god, were permanently abandoned, and his name erased from history. Archaeologists rediscovered him in the late 19th century. So how could the Great Hymn have reached Israelite poets of centuries later? There are two possibilities.

Perhaps Akhenaten’s ideas actually lived longer in Egypt than we think, with underground Atenists perpetuating the faith. If this was the case, then maybe the Hymn lasted there long enough to hitch a ride out of Egypt with the Israelites a century or two later. The most famous adherent of this view is Sigmund Freud, but this theory suffers from too many historical problems to see it as a probable explanation.[21]

The alternative is to posit that Atenist theology and literature reached Canaan even during Akhenaten’s own lifetime. Indeed, Egypt ruled Canaan during the time of Akhenaten, so this is very possible. One piece of evidence for this hypothesis is a letter from Abi-Milku of Tyre to Akhenaten (El-Amarna letter 147), which opens with a hymn of praise to the king:[22]

To the king, my lord, my god, my Sun: Message of Abi-Milku, your servant. My Lord is the sun, the one who has gone forth over the lands day after day. Like the mark of the sun, his good father who enlivens, with his good breath and returns with his north wind, he one who has placed all of the lands at rest with strength of might, who thundered[23] in heaven like Ba’al.

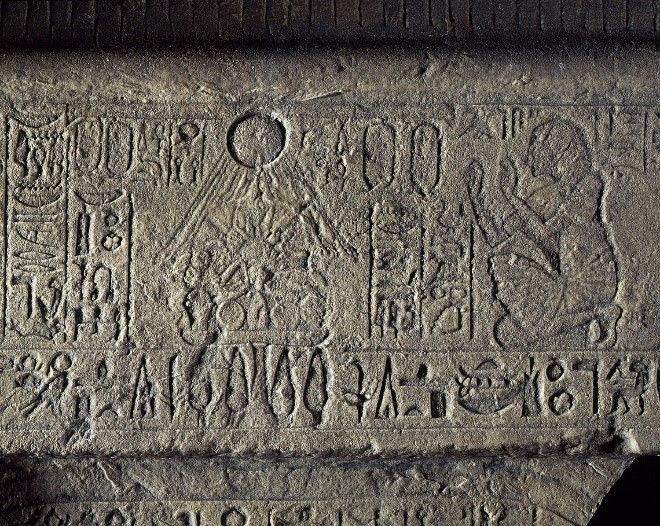

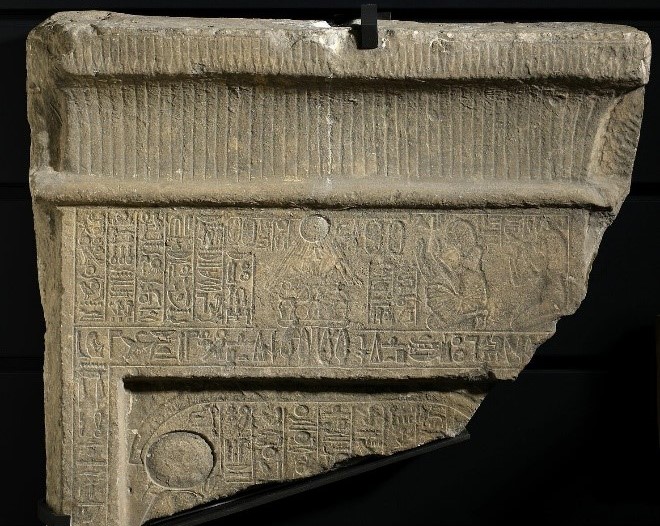

This poem is striking similar to a short hymn found within Amarna itself, in the tomb of a man named Pa-neḥesy,[24] whose inscription is now in the Louvre:

|

|

Adoration of Horakhty when he rises in his horizon, who gives his beauty to the whole land: ‘One lives after he has given his rays, and the land is bright at your birth every day, in order to cause all he created to live’.[25]

It thus seems probable that Akhenaten’s imagery, and likely even the Hymn itself, circulated in Canaan from the fourteenth century, presumably in translation. These texts and ideas made their way into Israelite circles in the following centuries, but by that time they were not identified as “Egyptian.”

E. Blessing for God and Earth: The Israelite Ending (vv. 31–35)

In addition to copying Aten imagery, Psalm 104 utilizes Semitic images and phraseology in its praise of God in all sections other than section four.[26] This Israelite nature of the psalm stands out in the final section, in which the psalmist arrives at the main point, the praise due God because of nature.

תהלים קד:לא יְהִי כְבוֹד יְ־הוָה לְעוֹלָם יִשְׂמַח יְ־הוָה בְּמַעֲשָׂיו.

Ps 104:31 May the glory of the LORD be forever! May the LORD rejoice in His works!

The psalmist then describes how the earth trembles when God looks upon it, and finally concludes on a personal note:

תהלים קד:לג אָשִׁירָה לַי־הוָה בְּחַיָּי אֲזַמְּרָה לֵאלֹהַי בְּעוֹדִי. קד:לד יֶעֱרַב עָלָיו שִׂיחִי אָנֹכִי אֶשְׂמַח בַּי־הוָה. קד:לה יִתַּמּוּ חַטָּאִים מִן הָאָרֶץ וּרְשָׁעִים עוֹד אֵינָם בָּרֲכִי נַפְשִׁי אֶת יְ־הוָה הַלְלוּ יָהּ.

Ps 104:33 I will sing to the LORD as long as I live; all my life I will chant hymns to my God. 104:34 May my prayer be pleasing to Him; I will rejoice in the LORD. 104:35 May sinners[27] disappear from the earth, and the wicked be no more. Bless the LORD, O my soul. Hallelujah.

The ending here is distinctly Israelite, and fits into the world of the psalms, in which the speaker petitions God directly, hoping the prayer will be heard. This Israelite imagery and framing masks the Egyptian origins of its core.

The Great Hymn of Rosh Chodesh

In Philip Glass’s opera Akhnaten, the Great Hymn is performed by the king himself; it is the one piece in the opera that is performed in the audience’s language, rather than the original languages, such as ancient Egyptian.[28] Once the hymn ends, an off-stage chorus performs excerpts from Psalm 104 in Hebrew. The screen then shows the words: “Egypt’s legacy in music and prose extends to the words of Psalm 104.” We can be more specific: Akhenaten’s legacy lives on in these words, found in the Bibles of all Jews and Christians, and recited by Jews around the world every Rosh Ḥodesh (New Moon), for which Psalm 104 serves as the song of the day.[29]

Appendix

The Great Hymn to the Aten (Assmann trans.)

Song 1: The Daily Circuit

Morning – beauty

Aten Hymn 1–5 Beautifully you rise in heaven’s lightland, living Aten, who allots life. You have dawned on the eastern horizon and have filled every land with your beauty.

Noon – dominion

Aten Hymn 6–12 You are beauteous, great, radiant, high over every land; your rays embrace the lands to the limit of all you have made. Being Re‘, you reach their limits and bend them down for the son whom you love. Though you are far, your rays are on earth; though one sees you, your strides are hidden.

Night – chaos

Aten Hymn 13–23 When you set in the western lightland, earth is in darkness in the condition of death. The sleepers are in their chambers, heads covered, one eye does not see the other, were they robbed of their gods under their heads, they don’t notice it. Every lion comes from its den, all the serpents bite. Darkness is a grave, Earth is in silence: Their creator has set in his lightland.

Morning – rebirth

Aten Hymn 24–44 At dawn you have risen in the lightland and are as radiant as the sundisk of daytime. You dispel the dark, you cast your rays, the Two Lands are in festivity daily. Humans awake, they stand on their feet, you have roused them. They wash and dress, their arms in adoration of your appearance; the entire land sets out to work. all beasts browse on their herbs, trees, herbs are sprouting; birds fly from their nests, their wings raised in adoration of your ka. All flocks frisk on their feet, all that fly up and alight, they live when you dawn for them. Ships fare north, fare south as well, every road lies open when you rise. The fish in the river dart before you – Your rays are in the midst of the sea.

Song 2: Creation

The child

Aten Hymn 45–54 [You] who make seed grow in women, who make water into men, who vivify the son in his mother’s womb, who soothe him to still his tears, you nurse in the womb. You giver of breath, to nourish all that he made. When he comes from the womb, to breathe, on the day of his birth, you open wide his mouth and supply his needs.

The chicken in the egg

Aten Hymn 55–62 The chicken in the egg: It speaks in the shell; You give it break within it to sustain it. You have fixed a term for it to break out from the egg. When it comes out from the egg, to speak at its term, it already walks on its legs when it comes forth from it.

Cosmic creation – multitude and diversity

Aten Hymn 63–76 How many are your deeds, though hidden from sight, O Sole God beside whom there is none! You made the earth following your heart when you were alone, with people, herds, and flocks; all upon earth that walks on legs, all on high that fly on wings, the foreign lands of Syria and Nubia, the land of Egypt. You set every man in his place, you supply his needs; everyone has his food, his lifetime is counted. Their tongues differ in speech, their characters likewise; their skins are distinct, for you distinguished the people.

The Two Niles

Aten Hymn 77–90 You made the Nile in the netherworld, you bring him when you will, to nourish the people, for you made them for yourself. Lord of all, who toils for them, Lord of all lands who shines for them, Sundisk of daytime, great in glory! All distant lands, you keep them alive; you made a heavenly Nile descend for them. He makes waves on the mountains like the sea, to drench their fields with what they need. How efficient are your plans, O Lord of eternity! A Nile from heaven for foreign people and for the creatures in the desert that walk on legs, but for Egypt the Nile who comes from the netherworld.

Song 3: Transformations: God, Nature, and the King

The Seasons

Aten Hymn 91–95 Your rays nurse all fields, when you shine, they live and grow for you. You made the seasons to foster all you made, winter, to cool them, summer, that they taste you.

Transformations in Heaven and on Earth

Aten Hymn 96–105 You made the sky far to shine therein, to see all that you make, while you are One, risen in your form of the living sundisk, shining and radiant, near and far. You make millions of forms from yourself alone, towns, villages, fields, road and river. All eyes behold you upon them, when you are above the earth as the disk of daytime.

The king, the unique knower

Aten Hymn 106–110 When you are gone there is no eye – whose eyesight you have created in order not to look upon yourself as the sole one of your creatures – but even then you are in my heart, there is no other one who knows you, only your son, Nefer-kheperu-Re Sole-one-of-Re (=Akhenaten), whom you have taught your ways and your might.

Time – Acting and Ruling

Aten Hymn 111–127 The earth comes into being by your hand as you made it, when you dawn, they live, when you set, they die; you yourself are lifetime, one lives by you. All eyes are on beauty until you set, all labor ceases when you rest in the west; but the rising one makes firm [every arm] for the king, and every leg moves since you founded the earth. You rouse them for your son who came from your body, the king who lives by ma‘at, the lord of the Two Lands, Nefer-kheperu-Re Sole-one-of-Re, the son of Re who lives by ma‘at, the lord of crowns, Akhenaten, great in his lifetime, and the great Queen whom he loves, the lady of the Two Lands Nefertiti, who lives and rejuvenates forever, eternally.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

July 1, 2022

|

Last Updated

December 25, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Aaron Koller is professor of Near Eastern studies at Yeshiva University, where he is chair of the Beren Department of Jewish Studies. His last book was Esther in Ancient Jewish Thought (Cambridge University Press), and his next is Unbinding Isaac: The Akedah in Jewish Thought (forthcoming from JPS/University of Nebraska Press in 2020); he is also the author of numerous studies in Semitic philology. Aaron has served as a visiting professor at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem and held research fellowships at the Albright Institute for Archaeological Research and the Hartman Institute. He lives in Queens, NY with his wife, Shira Hecht-Koller, and their children.

Essays on Related Topics: