Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Symposium

Psalm 137:9 - A Verse to Criticize

Personal Preface: The Difficulty with Dispassionate Analysis of Horrific Texts

Many believe that scholars of antiquity, including biblical scholars, are supposed to be objective, and that they should convey the meaning of the past to the present generation dispassionately. For me this is impossible when exploring texts such as Psalm 137:9, one of the most horrific biblical texts, which to paraphrase Alice (of Alice in Wonderland), only gets worse and worse the more deeply it is examined.

Given that the Bible functions as a source of inspiration, it is not sufficient to ask the typical scholarly questions about this verse—what the text meant in context, how v. 9 fits in the broader psalm, what the psalm’s structure is, when and why Psalm 137 was written, how its sentiments relate to other ancient psalms from this period, etc.—all the sorts of questions that biblical scholars are taught to ask. Nevertheless, the immediate horror of the verse does not obviate the need to ask these questions, some of which I explore below.

Composition History

Scholars debate the compositional history of Psalm 137, and how its final verses relate to the larger whole. Many, quite plausibly to my mind, suggest that vv. 1-6 comprised the original psalm, to which the last three verses have been appended. The evidence for this is suggestive, but not definitive. Vv. 1-6 must derive from the post-exilic period—Babylon is שָׁ֣ם, “there,” implying that the author is already back in Judah. On the other hand, the raw sentiments of vv. 7-9 imply a setting soon after the Babylonian exile.[1] In other words, vv. 7-9 likely existed as part of (separate) composition, written in the Babylonian exile, and they were later appended to vv. 1-6 of the psalm, resulting in the current nine verse psalm incorporated in the Psalter.

Yet, vv. 7-9 are now well-integrated into the psalm, through the repetition of the root ז-כ-ר, “to remember.” In its current form the psalm suggests that God must remember (ז-כ-ר) and punish Babylonian babies in return for “our” remembering Zion so very effectively: v. 1, בְּזָכְרֵ֗נוּ אֶת־צִיּֽוֹן (as we remembered Zion) and v. 6, תִּדְבַּ֥ק־לְשׁוֹנִ֨י ׀ לְחִכִּי֮ אִם־לֹ֪א אֶ֫זְכְּרֵ֥כִי (let my tongue stick to my palate if I cease to remember you). Additionally, in its final form, Ps 137 is a measure for measure (מידה כנגד מידה) psalm, as is made explicit in v. 8b, which leads right into v. 9: אַשְׁרֵ֥י שֶׁיְשַׁלֶּם־לָ֑ךְ אֶת־גְּ֝מוּלֵ֗ךְ שֶׁגָּמַ֥לְתְּ לָֽנוּ׃, “a blessing[2] on him who repays you in kind what you have inflicted on us.” The root ג-מ-ל is used in the Bible to express measure for measure retribution.

אַשְׁרֵ֤י שֶׁיֹּאחֵ֓ז וְנִפֵּ֬ץ אֶֽת עֹ֝לָלַ֗יִךְ אֶל הַסָּֽלַע Lexical Observations

The Use of the Word אשרי

Verse 8b lexically and syntactically prepares us for v. 9. It begins as well with אַשְׁרֵ֤י, a strong exclamatory form, which may be rendered as “O for the happiness of!” or “Blessings upon!” Elsewhere, אַשְׁרֵ֤י expresses joy for those who are saved by God (e.g. Deut 33:9), patiently wait for God’s deliverance (e.g. Isa 30:8), follow the path of the righteous (e.g. Ps 1:1), trust in God (e.g. Ps 34:9), reside in the Temple (e.g. Ps 84:5) or have lots of children (e.g. Ps 127:5).

Like the אַשְׁרֵ֤י of 8b, the same word in 9 is followed by the (late Biblical Hebrew) relative particle שֶׁ (rather than the earlier אֲשֶׁ֖ר), an imperfect (future) verb (שֶׁיְשַׁלֶּם שֶׁיֹּאחֵ֓ז) and a third person singular pronoun (לָ֑ךְ and the suffix of עֹ֝לָלַ֗יִךְ). This connects verses 8 and 9, thereby anchoring v. 9 well into the psalm.[3]

Seizing and Dashing

Uniquely in the Bible, v. 9 uses in conjunction the two verbs א-ח-ז, “to seize” and נ-פ-צ, “to smash or dash.” Seizing is not sufficient, smashing is not sufficient—both of these actions need to be accomplished for true happiness or blessing (אַשְׁרֵ֥י) to reign.

Furthermore, the second verb נ-פ-צ is in the pi‘el conjugation. It is not the case, as so many might have been taught in Hebrew school, that the main function of the pi‘el is to intensify the qal. One function of the pi‘el is “pluralising,” namely indicating “the action…involves either multiple subjects or objects.”[4] In other words, the pi‘el of נ-פ-צ draws a picture of fragmentation; it is not just that the babies are smashed, but that this dashing results in shattered baby fragments.

Children or Babies

It is hard to determine exactly what age range עֹלָלַ֗יִךְ designates, though Lamentations 4:4, עוֹלָלִים שָׁאֲלוּ לֶחֶם (“little children beg for bread”), suggests that these are not babes, but old enough to speak, likely toddlers. Thus, grasping them and smashing them again and again against a rock would require significant effort, and extreme callousness, as they are old enough to understand what is being done to them, and old enough to ask for mercy.

The Rock: A Geographical Location

The final word of the psalm is marked as definite (הַסָּֽלַע)—literally, “the rock.” Yet, English and Hebrew use definite articles such as “the” very differently. Furthermore, does the singular סלע indicate one rock, or is it being used generically or collectively, as “rocks”? These different possibilities are reflected in various translations, e.g. the JPS translates, “and dashes them against the rocks!” while the NRSV renders, “and dash them against the rock!”

To complicate matters even further— הַסָּֽלַע is known as a geographical location in Edom—The Rock. Near there, according to 2 Kings 14:7, the Judean King Amaziah massacred 10,000 Edomites; according to the parallel version in 2 Chr 25:12,

וַעֲשֶׂ֨רֶת אֲלָפִ֜ים חַיִּ֗ים שָׁבוּ֙ בְּנֵ֣י יְהוּדָ֔ה וַיְבִיא֖וּם לְרֹ֣אשׁ הַסָּ֑לַע וַיַּשְׁלִיכ֛וּם מֵֽרֹאשׁ־הַסֶּ֖לַע וְכֻלָּ֥ם נִבְקָֽעוּ:

Another 10,000 the men of Judah captured alive and brought to the top of Sela. They threw them down from the top of Sela and every one of them was burst open.

Thus, this psalm may conclude with a macabre pun: the Babylonian children are being smashed to pieces either on (a/the) rock(s) or at Sela, an important site of their Edomite allies.[5] A smashing baby pun!

Parallel Language with Jeremiah

A careful look at the uses of the vocabulary of v. 9 elsewhere in the Hebrew Bible brings us to Jeremiah 50-51, a long oracle against Babylon, which at some point originally concluded the book.[6] Most significantly, about half of the uses of the verb נ-פ-צ are found in Jeremiah 51:20-23:

נא:כ מַפֵּץ־אַתָּ֣ה לִ֔י

כְּלֵ֖י מִלְחָמָ֑ה

וְנִפַּצְתִּ֤י בְךָ֙ גּוֹיִ֔ם

וְהִשְׁחַתִּ֥י בְךָ֖ מַמְלָכֽוֹת:

נא:כא וְנִפַצְתִּ֣י בְךָ֔ ס֖וּס וְרֹֽכְב֑וֹ

וְנִפַּצְתִּ֣י בְךָ֔ רֶ֖כֶב וְרֹכְבֽוֹ:

נא:כב וְנִפַּצְתִּ֤י בְךָ֙ אִ֣ישׁ וְאִשָּׁ֔ה

וְנִפַּצְתִּ֥י בְךָ֖ זָקֵ֣ן וָנָ֑עַר

וְנִפַּצְתִּ֣י בְךָ֔ בָּח֖וּר וּבְתוּלָֽה:

נא:כג וְנִפַּצְתִּ֤י בְךָ֙ רֹעֶ֣ה וְעֶדְר֔וֹ

וְנִפַּצְתִּ֥י בְךָ֖ אִכָּ֣ר וְצִמְדּ֑וֹ

וְנִפַּצְתִּ֣י בְךָ֔ פַּח֖וֹת וּסְגָנִֽים:

51:20 You are My war club,

[My] weapons of battle;

With you I clubbed nations,

With you I destroyed kingdoms;

51:21 With you I clubbed horse and rider,

With you I clubbed chariot and driver,

51:22 With you I clubbed man and woman,

With you I clubbed graybeard and boy,

With you I clubbed youth and maiden;

51:23 With you I clubbed shepherd and flock,

With you I clubbed plowman and team,

With you I clubbed governors and prefects.

The vocabulary overlap between our psalm’s last three verses and Jeremiah 50-51 suggests that the author of Ps 137:7-9 likely knew Jeremiah 50-51, and based his addition, imprecating Babylon and Edom, on these chapters.[7] In other words, the images he uses and develops are traditional, and he is not at all original; like many ancient authors, in the Bible and elsewhere, he reuses earlier sources.

Smashing Babies in the Bible

Our authors’ dependence on the passage in Jeremiah likely explains why he pairs‘עולל with נ-פ-צ, rather than the expected ר-ט-ש, the more common verb used for describing smashed toddlers:

2 Kings 8.2

וַיֹּ֣אמֶר חֲזָאֵ֔ל מַדּ֖וּעַ אֲדֹנִ֣י בֹכֶ֑ה וַיֹּ֡אמֶר כִּֽי־יָדַ֡עְתִּי אֵ֣ת אֲשֶׁר־תַּעֲשֶׂה֩ לִבְנֵ֨י יִשְׂרָאֵ֜ל רָעָ֗ה מִבְצְרֵיהֶ֞ם תְּשַׁלַּ֤ח בָּאֵשׁ֙ וּבַחֻֽרֵיהֶם֙ בַּחֶ֣רֶב תַּהֲרֹ֔ג וְעֹלְלֵיהֶ֣ם תְּרַטֵּ֔שׁ וְהָרֹתֵיהֶ֖ם תְּבַקֵּֽעַ:

“Why does my lord weep?” asked Hazael. “Because I know,” he (=Elisha) replied, “what harm you will do to the Israelite people: you will set their fortresses on fire, put their young men to the sword, dash their little ones in pieces, and rip open their pregnant women.”

Hosea 14:1

תֶּאְשַׁם֙ שֹֽׁמְר֔וֹן כִּ֥י מָרְתָ֖ה בֵּֽאלֹהֶ֑יהָ בַּחֶ֣רֶב יִפֹּ֔לוּ עֹלְלֵיהֶ֣ם יְרֻטָּ֔שׁוּ וְהָרִיּוֹתָ֖יו יְבֻקָּֽעוּ:

Samaria must bear her guilt, for she has defied her God. They shall fall by the sword, their infants shall be dashed to death, and their women with child ripped open.

Nahum 3:10

גַּם־הִ֗יא לַגֹּלָה֙ הָלְכָ֣ה בַשֶּׁ֔בִי גַּ֧ם עֹלָלֶ֛יהָ יְרֻטְּשׁ֖וּ בְּרֹ֣אשׁ כָּל חוּצ֑וֹת וְעַל נִכְבַּדֶּ֙יהָ֙ יַדּ֣וּ גוֹרָ֔ל וְכָל גְּדוֹלֶ֖יהָ רֻתְּק֥וּ בַזִּקִּֽים:

Yet even she was exiled, she went into captivity. Her babes, too, were dashed in pieces at every street corner. Lots were cast for her honored men, and all her nobles were bound in chains.

Isaiah 13:16

וְעֹלְלֵיהֶ֥ם יְרֻטְּשׁ֖וּ לְעֵֽינֵיהֶ֑ם יִשַּׁ֙סּוּ֙ בָּֽתֵּיהֶ֔ם וּנְשֵׁיהֶ֖ם (תשגלנה) [תִּשָּׁכַֽבְנָה]:

And their babes shall be dashed to pieces in their sight, their homes shall be plundered, and their wives shall be raped.

In Kings and Hosea, the graphic parallel of ripping babies out of pregnant women is used, and in Isaiah—also an oracle against Babylon—the horrific element of לְעֵֽינֵיהֶ֑ם, “in their sight” is added. Some modern scholars, viewing such smashed baby verses as a group, suggest that they partake in a common literary trope that would not have been distressing to those who heard it. I find this suggestion apologetic and even offensive. Do such images ever lose their power?

Ancient Near Eastern Context

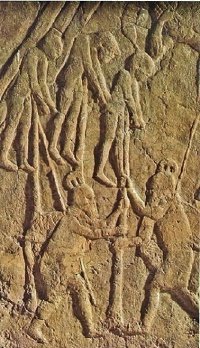

Lachish Relief. Bottom center detail of ME 124906 in the British Museum

In theory, our psalm’s last verse could be softened by seeing how ancient Israel’s neighbors, in particular the Assyrians, used gory images in both art and literature. For example, the Lachish reliefs, now in the British Museum, in depicting the Assyrian’s conquest of Lachish in 701 BCE, show three naked, impaled Judeans—a cruel warning to those who might rebel. In another relief, also from Sennacherib’s palace, heads lie in a heap near scribes, calmly recording the events of the day.

The Assyrian literary descriptions match the reliefs:

I cut their throats like lambs. I cut off their precious lives (as one cuts) a string. Like the many waters of a storm, I made (the contents of) their gullets and entrails run down upon the wide earth. My prancing steeds harnessed for my riding, plunged into the streams of their blood as (into) a river. The wheels of my war chariot, which brings low the wicked and the evil, were bespattered with blood and filth. With the bodies of their warriors I filled the plain, like grass. (Their) testicles I cut off, and tore out their privates like the seeds of cucumbers.[8]

Another text says, quite poetically,

With their blood, I dyed the mountain red like red wool.[9]

Yet, these Assyrian texts do not really soften our psalm’s final verse, for they do not typically emphasize brutal treatment of children; if anything, these texts highlight the Bible’s distinct fascination with this topos.[10]

Conclusion: Two Senses of the Phrase “Bible Critic”

Too often people accuse me of being a “Bible critic” because I engage in historical-critical research on the Bible. But in that phrase, “critical” does not mean to criticize, but to examine in a free and independent fashion, without particular religious preconceptions.[11] Thus, my main goal in using the tools of historical-critical methodology is to understand the Bible, in its wonderful and extensive variety—the good and bad, the beautiful and the ugly, within its ancient contexts.

But at times I am also a Bible critic, criticizing what the Bible says—and I would like to criticize Psalm 137:9 with all my heart, soul, and being. Applying critical tools to understand it well shows that it is even worse than it seems:

- It is worse than the Assyrian texts to which it is often compared,

- It makes a bad pun while discussing smashing toddlers to pieces,

- It exalts this action in the same way that elsewhere the Bible lauds having lots of children or following the divine path (אשרי).

Heaven help us all if we ignore the savageness of this text, and instead discuss it only as historical-critical philologists, in a dispassionate manner.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

February 28, 2015

|

Last Updated

February 12, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Marc Zvi Brettler is Bernice & Morton Lerner Distinguished Professor of Judaic Studies at Duke University, and Dora Golding Professor of Biblical Studies (Emeritus) at Brandeis University. He is author of many books and articles, including How to Read the Jewish Bible (also published in Hebrew), co-editor of The Jewish Study Bible and The Jewish Annotated New Testament (with Amy-Jill Levine), and co-author of The Bible and the Believer (with Peter Enns and Daniel J. Harrington), and The Bible With and Without Jesus: How Jews and Christians Read the Same Stories Differently (with Amy-Jill Levine). Brettler is a cofounder of TheTorah.com.

Essays on Related Topics: