Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Tarshish: The Origins of Solomon’s Silver

Nora Stone, a 9th cent. B.C.E. Phoenician inscription found in Sardinia. Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Cagliari. Olaf Tausch, Wikimedia Commons

When Solomon constructs the Temple, he makes many of the implements out of gold (1 Kgs 7:48–50).[1] Although he does not use silver, he has plenty of it stored along with the surplus gold in the Temple treasury:

מלכים א ז:נא וַתִּשְׁלַם כָּל הַמְּלָאכָה אֲשֶׁר עָשָׂה הַמֶּלֶךְ שְׁלֹמֹה בֵּית יְ־הוָה וַיָּבֵא שְׁלֹמֹה אֶת קָדְשֵׁי דָּוִד אָבִיו אֶת הַכֶּסֶף וְאֶת הַזָּהָב וְאֶת הַכֵּלִים נָתַן בְּאֹצְרוֹת בֵּית יְ־הוָה.

1 Kgs 7:51 When all the work that King Solomon had done in the House of YHWH was completed, Solomon brought in the sacred donations of his father David—the silver, the gold, and the vessels—and deposited them in the treasury of the House of YHWH.

Similarly, when Solomon builds his palace, we hear of only golden objects (1 Kgs 10:16–18).[2] The text explains that Solomon had so much silver, that it was barely considered precious:

מלכים א י:כא וְכֹל כְּלֵי מַשְׁקֵה הַמֶּלֶךְ שְׁלֹמֹה זָהָב וְכֹל כְּלֵי בֵּית יַעַר הַלְּבָנוֹן זָהָב סָגוּר אֵין כֶּסֶף לֹא נֶחְשָׁב בִּימֵי שְׁלֹמֹה לִמְאוּמָה.

1 Kgs 10:21 All King Solomon’s drinking vessels were of gold, and all the vessels of the House of the Forest of Lebanon were of pure gold; none were of silver—it was not considered as anything in the days of Solomon.[3]

Israel does not have silver or gold mines, so where does Solomon get this surplus of precious metals?

Where Is all This Gold and Silver From?

The book of Kings notes several sources for Solomon’s gold and silver:

A. Gifts from foreign visitors—When the Queen of Sheba comes, she brings gold with her, among other gifts (1 Kgs 10:10)[4]—and this is just one example of a more general phenomenon:

מלכים א י:כד וְכָל הָאָרֶץ מְבַקְשִׁים אֶת פְּנֵי שְׁלֹמֹה לִשְׁמֹעַ אֶת חָכְמָתוֹ אֲשֶׁר נָתַן אֱלֹהִים בְּלִבּוֹ. י:כה וְהֵמָּה מְבִאִים אִישׁ מִנְחָתוֹ כְּלֵי כֶסֶף וּכְלֵי זָהָב וּשְׂלָמוֹת וְנֵשֶׁק וּבְשָׂמִים סוּסִים וּפְרָדִים דְּבַר שָׁנָה בְּשָׁנָה.

1 Kgs 10:24 All the world came to pay homage to Solomon and to listen to the wisdom with which God had endowed him; 10:25 and each one would bring his tribute—silver and gold objects, robes, weapons and spices, horses and mules—year after year.

This fits a well-known pattern of giving precious gifts between royal parties in the ancient Mediterranean and Near Eastern societies during the Late Bronze Age.[5]

B. Tribute—Subject peoples would pay taxes or tribute:

מלכים א י:יד וַיְהִי מִשְׁקַל הַזָּהָב אֲשֶׁר בָּא לִשְׁלֹמֹה בְּשָׁנָה אֶחָת שֵׁשׁ מֵאוֹת שִׁשִּׁים וָשֵׁשׁ כִּכַּר זָהָב. י:טו לְבַד מֵאַנְשֵׁי הַתָּרִים וּמִסְחַר הָרֹכְלִים וְכָל מַלְכֵי הָעֶרֶב וּפַחוֹת הָאָרֶץ.

1 Kgs 10:14 The weight of the gold which Solomon received every year was 666 talents of gold, 10:15 besides what came from tradesmen, from the traffic of the merchants, and from all the kings of Arabia and the governors of the regions.

A classic example of this is the tribute Hezekiah pays to Sennacherib, mentioned both in the Bible (2 Kgs 18:13–16) and in Sennacherib’s prism.

C. Foreign Trade—Solomon’s ally, the Phoenician Hiram, king of Tyre (in modern Lebanon), imports gold from a place called Ophir, in Arabia or Africa, using a fleet of ships ostensibly embarking from Solomon’s Etzion-geber port (near Eilat) in the Gulf of Aqaba/Red Sea:

מלכים א י:יא וְגַם אֳנִי חִירָם אֲשֶׁר נָשָׂא זָהָב מֵאוֹפִיר הֵבִיא מֵאֹפִיר עֲצֵי אַלְמֻגִּים הַרְבֵּה מְאֹד וְאֶבֶן יְקָרָה.

1 Kgs 1:11 Moreover, Hiram’s fleet, which carried gold from Ophir, brought in from Ophir a huge quantity of almug wood and precious stones.

Later in the chapter, we hear of Solomon’s own Tarshish fleet, bringing back gold and silver once every three years:

מלכים א י:כב כִּי אֳנִי תַרְשִׁישׁ לַמֶּלֶךְ בַּיָּם עִם אֳנִי חִירָם אַחַת לְשָׁלֹשׁ שָׁנִים תָּבוֹא אֳנִי תַרְשִׁישׁ נֹשְׂאֵת זָהָב וָכֶסֶף שֶׁנְהַבִּים וְקֹפִים וְתֻכִּיִּים.

1 Kgs 10:22 For the king had a Tarshish fleet on the sea, along with Hiram’s fleet. Once every three years, the Tarshish fleet came in, bearing gold and silver, ivory, apes, and peacocks. [6]

The verse describes a joint venture between Solomon and Hiram working together to import precious metals along with other luxury goods to the Levant, in return for whatever these ships brought with them to export.[7] But what is the meaning of the term “Tarshish fleet”?

A Tarshish Fleet?

William Foxwell Albright (1891–1971), the great American archaeologist, argued in a 1941 article[8] that the term Tarshish is not meant as a geographical marker, describing where the ships go, but is an adjective describing what kind of ships Solomon had:[9]

It is highly probable that Tarshish was a Phoenician word meaning “mine” or “smelting plant”[10]… The expression ʾonî taršîš “tarshish-fleet,” is very interesting and may now be explained as meaning “refinery fleet,” i.e., a fleet of ships which brought the smelted metal home from colonial mins.[11]

A similar approach, albeit with a different translation of the term, was put forward by Mordechai Cogan in his commentary on the passage, who argues that both texts about Hiram’s expeditions are referring to the same fleet:

The designation “Tarshish Fleet” in no way implies that Solomon was involved in Tyre’s Mediterranean trade. Most agree that in the present context, the reference is to a type of ship, rather than to a particular destination—thus, a large oceangoing vessel. Influencing this judgement is the cargo of monkeys and peacocks, pointing in the direction of Africa rather than the Mediterranean.[12]

Further support of this view can be found in later in Kings:

מלכים א כב:מט יְהוֹשָׁפָט (עשר) [עָשָׂה] אֳנִיּוֹת תַּרְשִׁישׁ לָלֶכֶת אוֹפִירָה לַזָּהָב וְלֹא הָלָךְ כִּי (נשברה) [נִשְׁבְּרוּ] אֳנִיּוֹת בְּעֶצְיוֹן גָּבֶר. כב:נ אָז אָמַר אֲחַזְיָהוּ בֶן אַחְאָב אֶל יְהוֹשָׁפָט יֵלְכוּ עֲבָדַי עִם עֲבָדֶיךָ בָּאֳנִיּוֹת וְלֹא אָבָה יְהוֹשָׁפָט.

1 Kgs 22:49 Jehoshaphat constructed Tarshish ships to sail to Ophir for gold. But he did not sail because the ships were wrecked at Ezion-geber. 22:50 Then Ahaziah son of Ahab proposed to Jehoshaphat, “Let my servants sail on the ships with your servants”; but Jehoshaphat would not agree.[13]

One problem with translating tarshish as a type of vessel is that the book of Chronicles, in a retelling of Kings, clearly understands Tarshish as a toponym:

דברי הימים ב ט:כא כִּי אֳנִיּוֹת לַמֶּלֶךְ הֹלְכוֹת תַּרְשִׁישׁ עִם עַבְדֵי חוּרָם אַחַת לְשָׁלוֹשׁ שָׁנִים תָּבוֹאנָה אֳנִיּוֹת תַּרְשִׁישׁ נֹשְׂאוֹת זָהָב וָכֶסֶף שֶׁנְהַבִּים וְקוֹפִים וְתוּכִּיִּים.

2 Chron 9:21 The king’s fleet traveled to Tarshish with Huram’s servants. Once every three years, the Tarshish fleet came in, bearing gold and silver, ivory, apes, and peacocks.

The German Bible scholar Wilhelm Rudolph (1891–1987) argues that Chronicles misunderstood the term in Kings:

The original text (=1Kgs 10:22) says “the King had a Tarshish-Fleet on the sea,” where “tarshish-ship” is a term of quality… it does not mean that the ship actually goes to Tarshish… as the Chronicler misunderstood here. The reference is surely to the trips to Ophir (compare the imported products).[14]

These scholars are trying to make the account of Solomon’s Tarshish fleet work with the earlier description of a Red Sea fleet, and the mention of items of African origin. And yet, whether or not the Phoenicians had a Red Sea fleet, they certainly had one in the Mediterranean, which was their main source of income.

It seems more likely, therefore, that Tarshish is a toponym somewhere on the coast of the Mediterranean, as it is elsewhere in the Bible. This is how Chronicles as well as most interpreters throughout history have understood the term in this verse.

What Do We Know about Biblical Tarshish?

The most famous biblical reference to Tarshish appears in the book of Jonah. After YHWH commands Jonah to go to Nineveh in Assyria to convince them to repent, Jonah decides he does not want to fulfill this mission, and so he runs away:

יונה א:ג וַיָּקָם יוֹנָה לִבְרֹחַ תַּרְשִׁישָׁה מִלִּפְנֵי יְ־הוָה וַיֵּרֶד יָפוֹ וַיִּמְצָא אָנִיָּה בָּאָה תַרְשִׁישׁ וַיִּתֵּן שְׂכָרָהּ וַיֵּרֶד בָּהּ לָבוֹא עִמָּהֶם תַּרְשִׁישָׁה מִלִּפְנֵי יְ־הוָה.

Jonah 1:3 Jonah, however, started out to flee to Tarshish from YHWH’s service. He went down to Jaffa and found a ship going to Tarshish. He paid the fare and went aboard to sail with the others to Tarshish, away from the service of YHWH.

The implication is that Jonah is sailing to a place that is as far away as he (or the reader) can imagine. This fits with what the account of Solomon’s Tarshish fleet (1 Kgs 10:21) implies, that a round-trip merchant expedition to Tarshish took around three years. This also clearly implies access to Tarshish from the Mediterranean.

A Source for Silver: Jeremiah

Jeremiah’s taunt of idol worshippers, in which he mentions Tarshish as the source of silver (and perhaps gold), confirms that it was a place to acquire precious metals :

ירמיה י:ט כֶּסֶף מְרֻקָּע מִתַּרְשִׁישׁ יוּבָא וְזָהָב מֵאוּפָז מַעֲשֵׂה חָרָשׁ וִידֵי צוֹרֵף...

Jer 10:9 Silver beaten flat, that is brought from Tarshish, and gold meuphaz, the work of a craftsman and the goldsmith’s hands…

According to this verse, silver comes from Tarshish. The origin of the gold is less clear, and it depends on the meaning of the word מֵאוּפָז, meuphaz:

From Uphaz—Reading the text as is, the gold comes from an unknown place called Uphaz.[15]

Gold Plate—Some emend the text to say זהב מופז,[16] without the aleph, which would mean “gold plate,” though Shadal (Samuel David Luzzatto, 1800–1865) notes that it would be strange to have the gold worked before it arrived at the palace.[17]

Hendiadys—Others emend the text to read זהב ופז, a hendiadys meaning “gold and fine gold,” i.e., lots of gold,[18] though it is difficult to understand why the two letters, mem and aleph, would have been added.

From Ophir—Targum Jonathan reads וְדַהֲבָא מֵאוֹפִיר and the Syriac Peshitta reads ודהבא מן אופיר (ܘܕܗܒܐ ܡܢ ܐܘܦܝܪ), both meaning “gold from Ophir.”

If this latter reading is correct, it would fit with the dichotomy in 1 Kings mentioned above, that Ophir was famous for its gold and Tarshish for its silver.

Phoenician Silver Trade: Ezekiel

From Ezekiel’s “lament over Tyre,”[19] describing the greatness of Tyre before it was destroyed by the Babylonians, we learn that, at least in the decades before Ezekiel’s time, the Phoenicians of Tyre imported silver to the Levant from Tarshish, with their Tarshish ships:

יחזקאל כז:יב תַּרְשִׁישׁ סֹחַרְתֵּךְ מֵרֹב כָּל הוֹן בְּכֶסֶף בַּרְזֶל בְּדִיל וְעוֹפֶרֶת נָתְנוּ עִזְבוֹנָיִךְ.... כז:כה אֳנִיּוֹת תַּרְשִׁישׁ שָׁרוֹתַיִךְ מַעֲרָבֵךְ וַתִּמָּלְאִי וַתִּכְבְּדִי מְאֹד בְּלֵב יַמִּים.

Ezek 27:12 Tarshish traded with you because of your wealth of all kinds of goods; they bartered silver, iron, tin, and lead for your wares…. 27:25 The Tarshish ships were in the service of your trade. So you were full and richly laden on the high seas.

According to this, until Nebuchadnezzar’s conquest of Tyre, Phoenician ships would bring silver and other metals from Tarshish into the Levant. While Ezekiel is probably describing the reality in the 7th century B.C.E., Tyre had likely been involved in this trade at least as far back as the 8th century B.C.E., perhaps even earlier.

Tarshish in the Nora Stone

The trade connection between Tyre and Tarshish appears in “the Nora Stone,” a 9th century B.C.E. Phoenician stela engraved upon a 1.05-meter limestone slab (KAI 46).[20] The stela was found in 1773, near the archaeological site of Nora in Sardinia, in a secondary use context (i.e., as part of the building of another structure).

The letters are easy to read, but as there are no spaces or dividers marking words, the interpretation of this stone, especially its ending, is debated. Here is one possible reading with accompanying translation:

...בתרשש וגרש הא בשרדנ שלמ הא שלמ צבא מלכת נבנ ש בנ[21] נגר לפמי.

…to Tarshish. And he was driven to Sardinia. He is safe. Safe is the crew (or army) of the Queen.[22] [This] structure that the official built is dedicated to Pumi.

This short text is likely a thanksgiving inscription put up by a Tyrian official in gratitude for the ship having survived some dangerous event[23]—note the use of the word shalom twice. The final word, לפמי, could be a dedication to the Phoenician god Pumy, or may reflect the writing of the steal by an official of King Pumy.[24]

The final word of the otherwise missing opening line בתרשש “at/from Tarshish” seems to tell us either where they were headed or where they were coming from. They ended up in Sardinia, because they were driven out of somewhere, perhaps Tarshish, or perhaps some earlier port on the way to Tarshish. This confirms the biblical material that implies that Tarshish was part of the Phoenician trade circuit. But where more precisely is Tarshish was located?

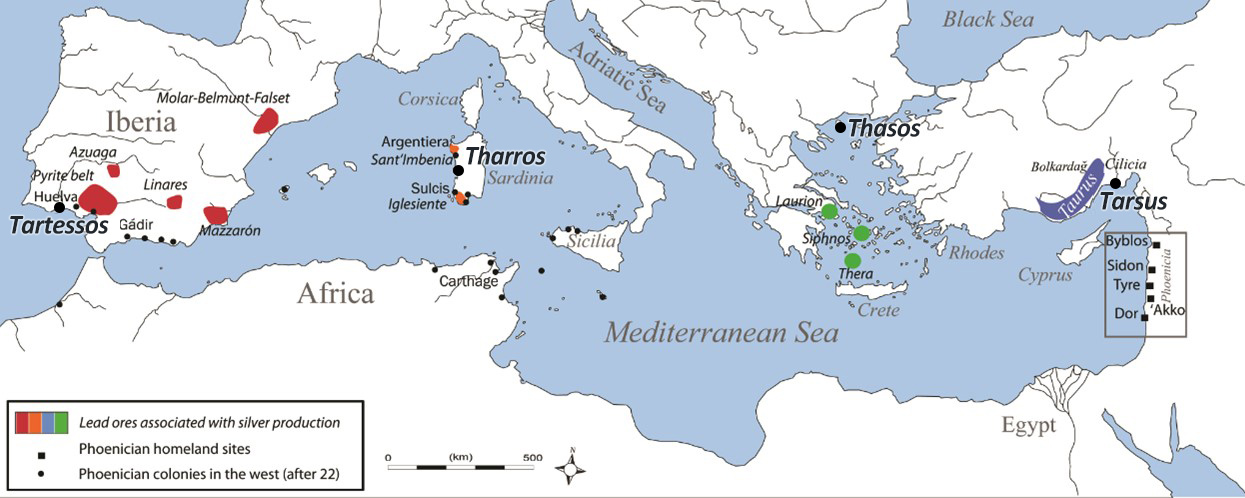

Many places in the ancient Mediterranean had names that sound like Tarshish. Including: Tarsus in Anatolia, Thasos in the Aegean, Tharros in Sardinia and Tartessos in Iberia [25] Looking at silver deposits in the ancient Mediterranean world and comparing them to the silver caches from the Iron Age Levant helps us locate this Tarshish.

Silver’s Fingerprint

Silver is produced from silver-rich lead deposits. Extracting silver from the lead is a two-step process: First, the lead-silver alloy must be separated out from the ore deposit, and then the silver needs to be separated from the lead and other accompanying metals.[26]

The chemical makeup of each deposit is distinct. Since silver is a result of extracting the metal from lead ore, every piece of silver has a small percentage of lead that remains from the lead ore. Lead (Pb 82) has four stable isotopes, and the ratio of the various isotopes in any given lead deposit is like a fingerprint, telling us the age of the ore (namely when the ore was formed), and of the accompanying silver in the ore. Since the lead deposits formed at different times, the composition of each, and the ratio of isotopes differ in each ore.

Silver, in the form of rods, cut ingots, and scrap silver served as a means of currency and exchange in the southern Levant, since the Middle Bronze Age.[27] This is evidenced by a total of 40 different silver hoards, found in various locations in this region.[28] The Levant, however, has no lead deposits, and thus any silver found in archaeological hordes must have been imported. The main silver-rich lead deposits in the Mediterranean and Near East were in Iran, Turkey, Aegean islands, Greece, Sardinia, and Spain.

Silver-rich lead ore deposits in the Mediterranean. Illustrations by Svetlana Matskevich

Silver-rich lead ore deposits in the Mediterranean. Illustrations by Svetlana Matskevich

When the Mycenean Empire collapsed at the end of the Late Bronze Age (ca. 1200 B.C.E.), the international trade network of the Mediterranean collapsed as well. This led to a shortage of silver in the southern Levant that lasted for two centuries.[29] Silver hoards from several contexts in the southern Levant (Megiddo, Beth Shean, Tel Keisan and Ashkelon) contained silver mixed with copper, evidence of this silver shortage. Pure silver in hoards is evident again only from the mid 10th century B.C.E., implying that silver was again being imported into the Levant.

Isotopic analysis of the many silver objects that were found from this period (mid-10th cent. B.C.E.) in the Land of Israel, in Dor and Akko, point to Turkey and Sardinia as the origin point of the silver.[30] This would suggest that Tarshish in Kings was either Tarsus in the Taurus mountains of Anatolia (modern Turkey) or perhaps Tharros on Sardinia.

The ʿEin Hofez Hoard: Isotope analysis shows that the silver originated in Spain. Image courtesy of the Collection of Israel Antiquities Authority by Warhaftig Venezian (photographer).

The ʿEin Hofez Hoard: Isotope analysis shows that the silver originated in Spain. Image courtesy of the Collection of Israel Antiquities Authority by Warhaftig Venezian (photographer).

In the 9th century, the main source of silver for the Levant switched to Spain, and remained there for the next two centuries (9th–8th centuries). Among the silver objects that came from Spain were a silver hoard from ʿEin Hofez (near Yokneam), a hoard from Tel ʿArad, and the largest hoard ever discovered in the Near East, from Eshtemoʿa, which included 23 kilograms of silver.[31]

Based on these findings, the Tarshish as the source of Phoenician silver in Jeremiah (10:9) and Ezekiel (27:12, 25), quoted above, refers to Tartessos on the Iberian Peninsula, as many scholars have suggested.

Notably, whereas Genesis 10:4 describes an Aegean Tarshish, which might imply Thasos as Tarshish, the silver from the southern Levant in the 10th–8th centuries does not come from there.

How Many Tarshishes?

The story of Solomon and Hiram’s joint ventures to Tarshish are set in the late tenth century, when the primary sources for silver in the southern Levant were Turkey and Sardinia. How does this fit with the references to silver from Tarshish in later biblical sources, which probably refer to Spain?

Many answers to this question are possible. We already mentioned above that tarshish could have been the name of the fleet, only later becoming the name of the site(s) from which silver was imported. Another possibility is that Tarshish in the Bible refers to multiple places. The Tarshish in the story of Solomon and Hiram refers either to Tarsus in Turkey or Tharros in Sardinia, while Jeremiah and Ezekiel are speaking of Tartessos in Spain. Perhaps the Phoenicians brought the name with them to Spain when they began exploiting new silver ores.

Finally, it is also possible that a later scribe, writing the story of Solomon and Hiram’s fleet travelling to get silver, projected the reality of his own time onto Solomon’s. While in the tenth century, the Phoenicians were travelling to Turkey and Sardinia, this scribe assumed that they were travelling to Tartessos in Iberia, as they did in his day, and thus mistakenly called Solomon and Hiram’s merchant ships the Tarshish fleet.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

March 1, 2022

|

Last Updated

November 29, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Tzilla Eshel is a lecturer at Haifa University's Zinman Institute of Archaeology, where she completed her M.A. (summa cum laude) and Ph.D. Her dissertation deals with the provenance of silver hoards from the Bronze and Iron Ages, and she has authored several articles dealing with the ancient use of silver.

Essays on Related Topics: