Edit article

Edit articleSeries

The 220-Year History of the Achaemenid Persian Empire

Room 52, in the British Museum with the Cyrus Cylinder created 539–538 BC. Wikimedia

Cyrus the Anointed of YHWH

The Bible is not generally complimentary when it comes to foreign kings. Cyrus the Great (d. 530 B.C.E.), the Persian king who ended the domination of Judah by Babylon, is a notable exception. Deutero-Isaiah, the anonymous prophet of the exilic period, declares that Cyrus is YHWH’s “anointed one” (mashiach)—a term generally reserved for Israelite kings such as Saul and David:

ישעיה מה:א כֹּה אָמַר יְ-הוָה לִמְשִׁיחוֹ לְכוֹרֶשׁ אֲשֶׁר הֶחֱזַקְתִּי בִימִינוֹ לְרַד לְפָנָיו גּוֹיִם וּמָתְנֵי מְלָכִים אֲפַתֵּחַ לִפְתֹּחַ לְפָנָיו דְּלָתַיִם וּשְׁעָרִים לֹא יִסָּגֵרוּ.

Isa. 45:1 Thus said YHWH to Cyrus, his anointed one — whose right hand He has grasped, treading down nations before him, ungirding the loins of kings, opening doors before him and letting no gate stay shut:

Deutero-Isaiah continues and waxes poetic about Cyrus:

ישעיה מה:ב אֲנִי לְפָנֶיךָ אֵלֵךְ וַהֲדוּרִים (אושר) [אֲיַשֵּׁר] דַּלְתוֹת נְחוּשָׁה אֲשַׁבֵּר וּבְרִיחֵי בַרְזֶל אֲגַדֵּעַ. מה:ג וְנָתַתִּי לְךָ אוֹצְרוֹת חֹשֶׁךְ וּמַטְמֻנֵי מִסְתָּרִים לְמַעַן תֵּדַע כִּי אֲנִי יְ-הוָה הַקּוֹרֵא בְשִׁמְךָ אֱלֹהֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל.

Isa 45:2 I will march before you and level the hills that loom up; I will shatter doors of bronze and cut down iron bars. 45:3 I will give you treasures concealed in the dark and secret hoards — So that you may know that it is I YHWH, the God of Israel, who call you by name.

Here, YHWH promises to make Cyrus a successful conqueror, adding the (doubtful) claim that Cyrus and the whole world (v. 6) will then recognize that Cyrus’ power is from the God of Israel.

Cyrus Commands the Rebuilding of the Temple

Historically speaking, what Cyrus thought about the God of Israel—if he thought about him at all—is unknown, but in the Bible, Cyrus recognizes YHWH and fulfills his commands.

Cyrus Servant of YHWH (Chronicles)

The book of Chronicles ends with a version of Cyrus’ famous proclamation allowing the Jews to return to Jerusalem and rebuild the Temple; in this version, Cyrus explicitly acknowledges YHWH:

דברי הימים ב לו:כג כֹּה אָמַר כּוֹרֶשׁ מֶלֶךְ פָּרַס כָּל מַמְלְכוֹת הָאָרֶץ נָתַן לִי יְ-הוָה אֱלֹהֵי הַשָּׁמַיִם וְהוּא פָקַד עָלַי לִבְנוֹת לוֹ בַיִת בִּירוּשָׁלִַם אֲשֶׁר בִּיהוּדָה מִי בָכֶם מִכָּל עַמּוֹ יְ-הוָה אֱלֹהָיו עִמּוֹ וְיָעַל.

2 Chron. 36:23 Thus said King Cyrus of Persia: “YHWH God of Heaven has given me all the kingdoms of the earth, and has charged me with building Him a House in Jerusalem, which is in Judah. Any one of you of all His people, YHWH his God be with him and let him go up.”

Build the Jerusalem Temple and the Persians Will Pay For It (Ezra)

The book of Ezra describes Cyrus’ order that the Temple in Jerusalem should be rebuilt and that the Persians would pay for it:

עזרא ו:ג בִּשְׁנַת חֲדָה לְכוֹרֶשׁ מַלְכָּא כּוֹרֶשׁ מַלְכָּא שָׂם טְעֵם בֵּית אֱלָהָא בִירוּשְׁלֶם בַּיְתָא יִתְבְּנֵא אֲתַר דִּי דָבְחִין דִּבְחִין… ו:ד …וְנִפְקְתָא מִן בֵּית מַלְכָּא תִּתְיְהִב. ו:ה וְאַף מָאנֵי בֵית אֱלָהָא דִּי דַהֲבָה וְכַסְפָּא דִּי נְבוּכַדְנֶצַּר הַנְפֵּק מִן הֵיכְלָא דִי בִירוּשְׁלֶם וְהֵיבֵל לְבָבֶל יַהֲתִיבוּן וִיהָךְ לְהֵיכְלָא דִי בִירוּשְׁלֶם לְאַתְרֵהּ וְתַחֵת בְּבֵית אֱלָהָא.

Ezra 6:3 In the first year of King Cyrus, King Cyrus issued an order concerning the House of God in Jerusalem: “Let the house be rebuilt, a place for offering sacrifices… 6:4 …The expenses shall be paid by the palace. 6:5 And the gold and silver vessels of the House of God which Nebuchadnezzar had taken away from the temple in Jerusalem and transported to Babylon shall be returned, and let each go back to the temple in Jerusalem where it belongs; you shall deposit it in the House of God.”

Although archaeology has discovered no text in which Cyrus actually speaks about Yehud (Judah) or the Jerusalem Temple, the attitude described here is reminiscent of that which we find in the Cyrus Cylinder, an Akkadian text written on behalf of Cyrus that describes his conquests as well as his domestic policy, according to which the nations he freed from their previous conquerors would be permitted to return to their homes and worship their gods as they saw fit.

The great historian of the Persian Empire, Pierre Briant (b. 1940), has this to say on the subject:

[T]he political and religious restoration of a city or community was accompanied by the return—absolutely essential to the repatriated people—of the statues of the god that had previously been deported to the former conqueror’s capital. It was exactly this that Cyrus did in Babylon. The “exceptional” character of the actions taken by Cyrus on behalf of Jerusalem thus arises only from the narrowly Judeocentric perspective of our sources.[1]

A Note about Our Sources for the Persian Period

The primary sources of information that scholars use to reconstruct the Persian period come, ironically, from the camp of Persia’s enemies, Greek historians who wrote about the exploits of the Persian kings.[2] In addition, we have documents such as the Cyrus Cylinder and Darius’ Behistun Inscription, as well as archaeological finds such as palaces, temples, tablets, etc., that help us understand matters from the Persian side.[3] We also have pieces of information from biblical texts about certain kings and policies.

No one source paints the whole picture of whatever event or era it describes, and certainly every historical account has its biases and inaccuracies. The job of the critical scholar is to gather all information possible, evaluate each source based on its date and likely bias, compare and contrast, sift what seems historical from what seems fanciful or polemical, and try to reconstruct the past to the best of his or her ability. Although historians debate certain details, the overall contours of Persian history are more-or-less agreed upon.[4]

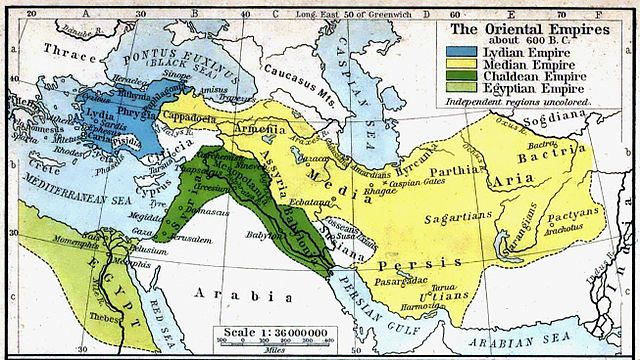

The Four Kingdoms on the Eve of Cyrus’ Conquests

In the year 549 B.C.E., four powers dominated the Ancient Near East; two large kingdoms (Egypt and Lydia) and two vast empires (Babylonia and Media).

- Egypt – With its capital in Sais in the Nile Delta, Egypt was ruled by the penultimate Pharaoh of the 26th (Saite) dynasty, Amasis II (570-526 B.C.E.).

- Lydia – A kingdom covering the western half of Anatolia (Turkey), with its capital in Sardis. It was ruled by King Croesus (560-546 B.C.E.), famous for his wealth.

- Babylonia/Chaldea – Under king Nabonidus (556-539 B.C.E.), Babylonia ruled from the city of Babylon (southern Iraq) in the east, up through Assyria (northern Iraq and Syria) and down through Lebanon, Israel, and Judah in the West.

- Media – The largest of the four, with its capital in Ecbatana,[5] King Astyages (585-550 B.C.E.) ruled from Bactria in the east (Turkmenistan), through Parthia, Persia (Iran), and Armenia, up to Cappadocia (eastern Turkey) on the border of Lydia in the west.

Two Vassal States

Babylonia and Media had vassal states that were loosely part of their respective empires and paid tribute while maintaining their own king and quasi-independent status. Two example of such vassal states are:

Elam/Susiana (to Babylonia) – a polity long tied to Persia,[6] with its capital in Susa (=Shushan; eastern Iran, bordering on Iraq). The (final) king’s name may have been Ummanish.[7]

Persia (to Media) – Centered in the city of Anshan (lower Iran). The king of this polity, Cyrus II, was the maternal grandson of King Astyages of Media.[8]

Cyrus’ Meteoric Rise

The world changed in 549 B.C.E., when Cyrus rebelled against his grandfather and won. Whether Cyrus was particularly charismatic, a political dynamo, a military genius, or some combination thereof is unknown, but his small polity defeated the army of the great Median Empire handily, and many in the Median army quickly joined him. Famously, he allowed his grandfather to live out the rest of his life on a royal pension.

Conquest of Lydia

With the new Persian Empire sitting on his border, Croesus of Lydia attacked Cyrus.[9] After a protracted war, Lydia’s capital city, Sardis, fell in 546 B.C.E.; King Croesus was taken prisoner and Lydia was added to the Persian Empire.

Conquest of Elam – Reunifying Persia

Having defeated Lydia, Cyrus turned his attention to the “reunification” of Persia. He conquered Elam, taking its capital, Susa in 540 B.C.E., effectively removing it from the orbit of the Babylonian empire and making it part of his new Persian-Median empire. (We have no knowledge of what happened to the last Elamite king.)

The Conquest of Babylon

Cyrus invaded Babylonia proper in 539 B.C.E., defeating Nabonidus and his Babylonian army at the battle of Opis (Baghdad). The city of Sippar fell without even a skirmish and Babylon followed suit after a brief siege.

Nabonidus or Belshazzar?

Nabonidus does not appear to have been in the city at the time of its capture (sources are unclear on this point), which is likely why the famous scene in Daniel has his son, Belshazzar, and not him feasting on the night Babylon was taken. The author of Daniel mistakenly believes Belshazzar to have been the king:

דניאל ה:א בֵּלְשַׁאצַּר מַלְכָּא עֲבַד לְחֶם רַב לְרַבְרְבָנוֹהִי אֲלַף וְלָקֳבֵל אַלְפָּא חַמְרָא שָׁתֵה. ה:ב בֵּלְשַׁאצַּר אֲמַר בִּטְעֵם חַמְרָא לְהַיְתָיָה לְמָאנֵי דַּהֲבָא וְכַסְפָּא דִּי הַנְפֵּק נְבוּכַדְנֶצַּר אֲבוּהִי מִן הֵיכְלָא דִּי בִירוּשְׁלֶם וְיִשְׁתּוֹן בְּהוֹן מַלְכָּא וְרַבְרְבָנוֹהִי שֵׁגְלָתֵהּ וּלְחֵנָתֵהּ…. ה:ל בֵּהּ בְּלֵילְיָא קְטִיל בֵּלְאשַׁצַּר מַלְכָּא(כשדיא) [כַשְׂדָּאָה].

Dan 5:1 King Belshazzar gave a great banquet for his thousand nobles, and in the presence of the thousand he drank wine. 5:2 Under the influence of the wine, Belshazzar ordered the gold and silver vessels that his father Nebuchadnezzar[10] had taken out of the temple at Jerusalem to be brought so that the king and his nobles, his consorts, and his concubines could drink from them.… 5:30That very night, Belshazzar, the Chaldean king, was killed.

Capture of Nabonidus

Nabonidus was captured soon after the city fell, and the Babylonian Empire became part of Cyrus’ Persian Empire. Persian sources claim that the citizens of Babylon preferred Cyrus to Nabonidus and opened the gates for him but this is likely propaganda. Either way, Cyrus’ conquest put an end to Babylonia’s century of empire and self-rule.

Cambyses II and the Conquest of Egypt

Cyrus never conquered the fourth great kingdom of the ANE, Egypt. His final campaign, launched in 530 B.C.E., was against the Massagetae of Central Asia (modern day Uzbekistan), and he died during this campaign. His son, Cambyses II (530-522 B.C.E.), launched a campaign against Egypt in 525 B.C.E, ruled by the final Pharaoh of the Saite dynasty, Psamtik (or, in its Greek form, Psammetichus) III.

Psamtik III engaged the Persians in what is known as the (first) battle of Pelusium (525 B.C.E.), in the Sinai wilderness, and lost.[11] He retreated to Memphis, the ancient capital of northern Egypt, which was then taken after a moderate siege. In keeping with his father’s practice, Cambyses did not execute the captured monarch, but did have himself crowned Pharaoh, ending the reign of the Saite dynasty.

Cambyses and the Jews of Elephantine

Although Cambyses is not mentioned in the Bible, he comes up in the petition of the Jews of Elephantine to Bagoas, the Persian governor of Judea, written in 407 B.C.E. (discussed later in the section on Darius II). The Jewish temple of Elephantine had been destroyed, and as part of their request to receive permission to rebuild it, they claim that the temple had stood from even before Cambyses conquered Egypt, and that whereas he destroyed a number of Egyptian temples, he allowed the Jewish one to remain standing.[12]

Darius’ Coup

In 522 B.C.E., Cambyses was called back to the capital because of a rebellion in Persia itself. On the way back, during a skirmish in Syria, he was injured in the leg, and died of gangrene. His brother, Bardiya (Smerdis in Greek sources), inherited the throne. However, his reign was not to last.

During this time, a charismatic and powerful general named Darius son of Hystaspes publicly claimed that “the real Bardiya” had been murdered by a magus named Guamata, and that the latter was now posing as Bardiya. Darius also claimed that he (Darius) was of royal blood, and that his ancestor Achaemenis (from which the name of the dynasty, “Achaemenid,” derives) was also the ancestor of Cyrus, making Darius a distant cousin of the royal family. As such, Darius “took it upon himself” to rid the kingdom of the fraudulent Bardia (really Guamata) and successfully took the throne himself.

It seems more than likely that this entire claim was invented to give Darius an excuse to take power, and that, in reality, he was the usurper who killed the son of Cyrus and Cambyses’ legitimate successor. Whatever the truth may be, the royal family for the next two centuries of Persian rule were descendants of Darius and are referred to as Achaemenids, after the “common” royal ancestor of Darius and Cyrus.

Darius’ Rule

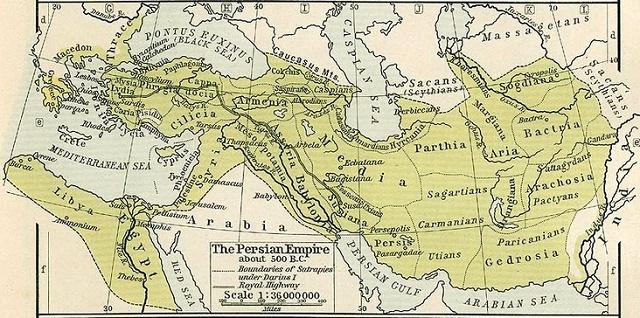

Darius I, also known as Darius the Great, ruled the Persian Empire for 36 years (522-486 B.C.E.). The beginning of his reign was filled with rebellions that he needed to put down, but after this, he had extended the reach of the Persian Empire on all sides, from the Indus River on the east to Sudan and Macedonia on the west.

His powers of organization matched his military prowess, and it was under his rule that the division of the empire into satrapies (districts ruled by governors called “satraps”) was finalized. Darius also built royal residences in two Persian cities, Susa (Shushan) and Persepolis, to replace the Median city Ecbatana as capitals.

Darius Rebuilds the Temple and the Persians Pay for It (Ezra)

The Bible knows Darius as the king during whose reign the rebuilding of the temple was completed, and thus he is mentioned fondly (Hag. 1:15, Ezra 4:5, 24). In fact, the book of Ezra describes Darius’ enthusiastic acceptance of Cyrus’ decree endorsing the rebuilding of the Jerusalem Temple:

עזרא ו:ז שְׁבֻקוּ לַעֲבִידַת בֵּית אֱלָהָא דֵךְ פַּחַת יְהוּדָיֵא וּלְשָׂבֵי יְהוּדָיֵא בֵּית אֱלָהָא דֵךְ יִבְנוֹן עַל אַתְרֵהּ. ו:ח וּמִנִּי שִׂים טְעֵם לְמָא דִי תַעַבְדוּן עִם שָׂבֵי יְהוּדָיֵא אִלֵּךְ לְמִבְנֵא בֵּית אֱלָהָא דֵךְ וּמִנִּכְסֵי מַלְכָּא דִּי מִדַּת עֲבַר נַהֲרָה אָסְפַּרְנָא נִפְקְתָא תֶּהֱוֵא מִתְיַהֲבָא לְגֻבְרַיָּא אִלֵּךְ דִּי לָא לְבַטָּלָא….

Ezra 6:7 Allow the work of this House of God to go on; let the governor of the Jews and the elders of the Jews rebuild this House of God on its site. 6:8 And I hereby issue an order concerning what you must do to help these elders of the Jews rebuild this House of God: the expenses are to be paid to these men with dispatch out of the resources of the king, derived from the taxes of the province of Beyond the River, so that the work not be stopped…

Darius even curses anyone who tries to stop this initiative.

עזרא ו:יא וּמִנִּי שִׂים טְעֵם דִּי כָל אֱנָשׁ דִּי יְהַשְׁנֵא פִּתְגָמָא דְנָה יִתְנְסַח אָע מִן בַּיְתֵהּ וּזְקִיף יִתְמְחֵא עֲלֹהִי וּבַיְתֵהּ נְוָלוּ יִתְעֲבֵד עַל דְּנָה. ו:יב וֵאלָהָא דִּי שַׁכִּן שְׁמֵהּ תַּמָּה יְמַגַּר כָּל מֶלֶךְ וְעַם דִּי יִשְׁלַח יְדֵהּ לְהַשְׁנָיָה לְחַבָּלָה בֵּית אֱלָהָא דֵךְ דִּי בִירוּשְׁלֶם אֲנָה דָרְיָוֶשׁ שָׂמֶת טְעֵם אָסְפַּרְנָא יִתְעֲבִד.

Ezra 6:11 I also issue an order that whoever alters this decree shall have a beam removed from his house, and he shall be impaled on it and his house confiscated. 6:12 And may the God who established His name there cause the downfall of any king or nation that undertakes to alter or damage that House of God in Jerusalem. I, Darius, have issued the decree; let it be carried out with dispatch.

The book of Ezra’s hyperbolic description of Darius’ enthusiastic support of the Temple underlines how fond the biblical authors were of the king who allowed the Temple to be rebuilt.

Xerxes the Great

Invasion of Greece

The rule of Darius’s son and successor, Xerxes (Ahasuerus in Hebrew, 486-465), is most significant historically because of his attempt to conquer Greece. In command of an enormous army, Xerxes first won a victory in Thermopylae against the combined Greek forces of a few hundred men led by King Leonidas of Sparta (480 B.C.E.).[13] The bulk of the Greek forces retreated to the bay of Salamis, and surprisingly defeated Xerxes and his Persian forces in a naval battle. Although the defeat was not substantial, militarily speaking, it was the first chink in the Persian army’s reputation. One of the final lines in Megillat Esther is possibly a satirical wink at Xerxes’ failed attempt to conquer Greece.

וַיָּשֶׂם הַמֶּלֶךְ (אחשרש) [אֲחַשְׁוֵרוֹשׁ] מַס עַל־הָאָרֶץ וְאִיֵּי הַיָּם:

King Ahasuerus imposed tribute on the mainland and the [Greek] islands.

Xerxes’ failed attempt to conquer Greece mobilized the Greek city-states and seems to have been a catalyst for Greek military power. This began with the formation of the Delian league under Athens, a group of Greek islands and city-states who launched small attacks against Persia’s Ionian (=Greek) holdings. Although these attacks had little immediate effect on Persia, this trend led to the eventual consolidation of Greek power, culminating in the Greek conquest of Persia a little more than a century later.

The Harem

Xerxes’ empire remained more or less the same as that of Darius, his father. Also, like his father, Xerxes built up the Persian capitals, including a new palace in Persepolis called “the Harem,”[14] since it housed his many wives. Xerxes’ opulent court is also the setting of the book of Esther, and its focus on the harem of Ahasuerus (בית הנשים, 2:11) is likely inspired by some knowledge of this tendency on the part of Persian kings in general, perhaps even Xerxes in particular.

Problem with Jews

Xerxes is mentioned in the book of Ezra as a king during whose time some sort of accusation was leveled against Judah, but we do not know the details:

עזרא וּבְמַלְכוּת אֲחַשְׁוֵרוֹשׁ בִּתְחִלַּת מַלְכוּתוֹ כָּתְבוּ שִׂטְנָה עַל יֹשְׁבֵי יְהוּדָה וִירוּשָׁלִָם.

Ezra 4:6 And in the reign of Ahasuerus, at the start of his reign, they drew up an accusation against the inhabitants of Judah and Jerusalem.

Assassination

Xerxes was assassinated in 465 B.C.E. The plot seems to have been hatched by a high-ranking official, Artabanus, but why he did so and how the plot unfolded is lost in the dramaticized versions preserved by the Greeks. Megillat Esther’s story of Bigtan and Teresh’s attempted assassination of Xerxes (2:21-23) may be inspired by knowledge of Xerxes’ demise.

Artaxerxes I

Although Xerxes had three sons from his wife Amestris (Hystaspes, Darius, and Artaxerxes), the youngest ended up with the throne. Artaxerxes took the throne as a boy and had a long rule (465-424 B.C.E.). Like his grandfather Darius, he faced a number of rebellions throughout the empire. Especially taxing was a ten-year rebellion in Egypt (464-454) in addition to the usual skirmishes with Athens.

Ezra’s Mission to Enforce the Laws of the Torah

According to the book of Ezra, fifty years after the rebuilding of the Temple (516 B.C.E.), in the fifth year of his reign, Artaxerxes I gives funds to Ezra and his followers to return to Judah, to appoint judges, and to enforce the laws of the Torah (Ezra ch. 7):[15]

עזרא ז:כא וּמִנִּי אֲנָה אַרְתַּחְשַׁסְתְּא מַלְכָּא שִׂים טְעֵם לְכֹל גִּזַּבְרַיָּא דִּי בַּעֲבַר נַהֲרָה דִּי כָל דִּי יִשְׁאֲלֶנְכוֹן עֶזְרָא כָהֲנָה סָפַר דָּתָא דִּי אֱלָהּ שְׁמַיָּא אָסְפַּרְנָא יִתְעֲבִד….ז:כג כָּל דִּי מִן טַעַם אֱלָהּ שְׁמַיָּא יִתְעֲבֵד אַדְרַזְדָּא לְבֵית אֱלָהּ שְׁמַיָּא דִּי לְמָה לֶהֱוֵא קְצַף עַל מַלְכוּת מַלְכָּא וּבְנוֹהִי….ז:כה וְאַנְתְּ עֶזְרָא כְּחָכְמַת אֱלָהָךְ דִּי בִידָךְ מֶנִּי שָׁפְטִין וְדַיָּנִין דִּי לֶהֱוֹן דאנין [דָּאיְנִין] לְכָל עַמָּה דִּי בַּעֲבַר נַהֲרָה לְכָל יָדְעֵי דָּתֵי אֱלָהָךְ וְדִי לָא יָדַע תְּהוֹדְעוּן.

Ezra 7:21 I, King Artaxerxes, for my part, hereby issue an order to all the treasurers in the province of Beyond the River that whatever request Ezra the priest, scholar in the law of the God of Heaven, makes of you is to be fulfilled with dispatch… 7:23 Whatever is by order of the God of Heaven must be carried out diligently for the House of the God of Heaven, else wrath will come upon the king and his sons… 7:25 And you, Ezra, by the divine wisdom you possess, appoint magistrates and judges to judge all the people in the province of Beyond the River who know the laws of your God, and to teach those who do not know them.[16]

Nehemiah Sent to Rebuild the Wall

In the book of Nehemiah, we are told that Artaxerxes had a Judean high official (a royal eunuch) named Nehemiah who upon hearing of how Jerusalem was in ruins, falls to weeping. Artaxerxes notices that his trusted servant is sad and asks him what is wrong, and Nehemiah tells him about his homeland and asks for permission to go to Judah and repair the city. The king, with his consort seated at his side, agrees to this:[17]

נחמיה ב:א וַיְהִי בְּחֹדֶשׁ נִיסָן שְׁנַת עֶשְׂרִים לְאַרְתַּחְשַׁסְתְּא הַמֶּלֶךְ… ב:ד וַיֹּאמֶר לִי הַמֶּלֶךְ עַל מַה זֶּה אַתָּה מְבַקֵּשׁ וָאֶתְפַּלֵּל אֶל אֱלֹהֵי הַשָּׁמָיִם. ב:ה וָאֹמַר לַמֶּלֶךְ אִם עַל הַמֶּלֶךְ טוֹב וְאִם יִיטַב עַבְדְּךָ לְפָנֶיךָ אֲשֶׁר תִּשְׁלָחֵנִי אֶל יְהוּדָה אֶל עִיר קִבְרוֹת אֲבֹתַי וְאֶבְנֶנָּה.

Neh 2:1 In the month of Nisan, in the twentieth year of King Artaxerxes… 2:4 The king said to me, “What is your request?” With a prayer to the God of Heaven, 2:5 I answered the king, “If it please the king, and if your servant has found favor with you, send me to Judah, to the city of my ancestors’ graves, to rebuild it.”

Artaxerxes then agrees to send Nehemiah as governor of Judea, and he proceeds to rebuild the wall around the city.

Although both the story of Nehemiah and Ezra are almost certainly heavily embellished, these accounts show that the biblical authors looked kindly on this king of Persia, seeing him as a political and even religious ally. Artaxerxes is the last Persian king mentioned by the Bible.

Xerxes II – Artaxerxes I’s Failed Successor

Artaxerxes I died in 425 B.C.E., and the succession after him was a mess. He had one son with his queen, who was crowned Xerxes II, but he was assassinated while drunk by his half-brother Sogdianus after only 45 days on the throne. Sogdianus, however, was unable to gather sufficient support, and another half-brother, Ochus, took the throne, ruling under the royal name Darius II.

Darius II and the Rebellion in Egypt

Little is known about Darius II’s reign (423-405/4 B.C.E.). Some highlights are his putting down a rebellion in Media in 409 B.C.E., and his joining with Sparta against Athens in an attempt to squash Athenian power. The Persian forces were led by one of Darius II’s son’s, Cyrus the Younger. It was during Darius II’s reign that Egypt finally launched a successful rebellion (411-404 B.C.E.), declaring itself independent under the founder and only ruler of the 28th dynasty, Pharaoh Amarteus (404-398 B.C.E).

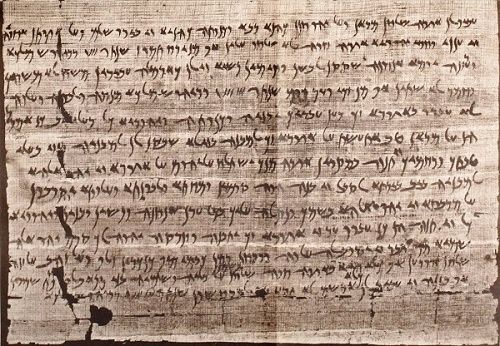

The Passover Letter to the Jews in Elephantine (Yeb)

In a letter dated to year 5 of Darius II (419 b.c.e.), a Judean official named Hananiah reports to the Jews in Elephantine that King Darius himself urges them to keep the Festival of Unleavened Bread properly:

Now, this year, the fifth year of King Darius, word was sent from the king to Arsa[mes saying, “Authorize a festival of unleavened bread for the Jew]ish [garrison]. …Be (ritually) clean and take heed. [Do n]o work [on the 15th or the 21st day, no]r drink [beer, nor eat] anything [in] which the[re is] leaven [from the 14th at] sundown until the 21st of Nis[an. For seven days it shall not be seen among you. Do not br]ing it into your dwellings but seal (it) up between these date[s. By order of King Darius. To] my brethren Yedoniah and the Jewish garrison, your brother Hanani[ah].

It is difficult to believe that Darius II was specifically concerned with chametz on Pesach, but it seems likely that the authorities in Jerusalem held a certain amount of authority over Jews in the empire, and used this authority to enforce a Jewish practice they wished emphasized.[18]

Destruction of the Jewish Yahu (=YHWH) Temple in Elephantine

As mentioned above, the Jews of Elephantine had their own temple. In the 14th year of Darius II (409 B.C.E.), while the Persian satrap Arsames was absent from Egypt helping Darius II put down rebellions in other places, the Egyptians appealed to the local Persian magistrate, Vidranga, asking him to destroy the Jewish Temple in Elephantine. This he did, sending his own son, Naphaina, commander of the local garrison, to carry out the attack. The Egyptian appeal was likely instigated by the priests of the ram-headed god, Khnum, because of the animal sacrifice practiced in the Jewish temple.[19]

The Jews of Elephantine wrote a letter to Bagoas, the Persian satrap of Yehud province (Judea), dated to 407 B.C.E., asking him to help them get permission to rebuild their temple. They also wrote to Sanballat, the satrap of Samaria (and a Samaritan himself), to Sanballat’s two sons Deliah and Shelemiah, who governed along with him, as well as to the high priest of the Temple in Jerusalem, Johanan ben Eliashib, with the same request for help. The Jews of Elephantine received a response from Deliah and Bagoas:

You may say in Egypt before Arsames about the Altar-house of the God of Heaven which was built in Elephantine the fortress formerly before Cambyses, (and) which that wicked Vidranga demolished in the year 14 of King Darius: to (re)build it on its site as it was formerly and they shall offer the meal-offering and the incense upon that altar just as formerly was done.

Two things are worth noting. First, the satraps of Judea and Samaria appear to be able to tell the satrap of Egypt what is permissible and expected with regard to the Jews in his province. Second, permission to rebuild the temple did not come with permission to offer animal sacrifices, ostensibly to avoid offending the Khnum priests again. This point is emphasized in yet another letter, likely to Arsames, governor of Egypt, that “sheep, ox, and goat are not made there as burnt-offering, but [only] incense [and] meal offerings.”[20] The temple was rebuilt but was destroyed again soon after, during the period of Egyptian independence from Persia.

The Early to Mid-4th Century B.C.E. Persia:

A Brief Overview

Artaxerxes II

Darius II’s son and heir, Artaxerxes II (404-358 B.C.E.) was unable to turn his attention to Egypt for a while, since his brother, Cyrus the Younger, rebelled against him with the help of Greek mercenaries. The rebellion lasted three years, and Cyrus the Younger was killed in 401 B.C.E.

For the next few years, Artaxerxes II fought an extended battle against the forces of the Spartan king, Ageselius, in his attempt to retake much of the Aegean holdings that had been lost to Persia over the years. This confrontation ended in a Persian victory. Artaxerxes II was only partially successful in his attempts to retake Egypt, however, which remained quasi-independent of Persia.

Artaxerxes III

Artaxerxes II was succeeded by his eldest son, Artaxerxes III (351-338). His rule began with revolts in Asia Minor, Phoenicia, and Cyprus, but the most significant event was when Pharaoh Nectanebo II (360-342 B.C.E.), the last native king of Egypt, declared Egypt to be entirely free of Persia. It was during this Pharaoh’s rule that the Jewish temple in Elephantine was permanently destroyed, to make way for an expansion to the neighboring temple of Khnum.

After dealing with the other rebellions, Artaxerxes III led a campaign to reconquer Egypt in 343-342 B.C.E. The battle was fought in the same place where Cambysus II conquered Egypt from Psamtik III two centuries earlier, and is, thus, also known as the (second) Battle of Pelusium (343 B.C.E.). Nectanebo escaped to Nubia, and Artaxerxes III marched into Memphis, had himself crowned as Pharaoh, and installed a Persian satrap as governor. He thereby reclaimed Egypt as a Persian province for the first time since his grandfather, Darius II, had lost it sixty years earlier.

At the same time that Artaxerxes III was consolidating his power in Persia, Philip II of Macedon (359-336 B.C.E.) was consolidating his power over Greece. The clash of these two kingdoms under the rule of their respective successors would end the Persian Empire and initiate the Greek or Hellenistic period.

Artaxerxes IV

Artaxerxes III had a powerful vizier named Bagoas.[21] At some point, the vizier found himself at odds with his king, and, in order to protect himself and his position, he assassinated Artaxerxes III and most of the royal family, placing the youngest son Arses on the throne, who took the name Artaxerxes IV. He ruled for two years (338-336 B.C.E.), but when Bagoas got wind of Artaxerxes IV’s plan to kill him, he had the young monarch assassinated and put the deceased monarch’s cousin, Darius III, on the throne in his stead.

Darius III, Alexander the Great and the Fall of Persia

Darius III (336-330 B.C.E.) was the final king of the Persian Empire. In 334, Alexander the Great (356-323 B.C.E.), who had taken over the Macedonian-Greek kingdom after his father’s assassination in 336 B.C.E., crossed the Dardenelles and landed in Turkey. The next few years was a sequence of alternating battles and peace negotiations.

The most decisive battles were the Battle of Granicus in northwestern Turkey (334 B.C.E.), the Battle of Issus in southern Turkey on the Mediterranean coast (333 B.C.E.), and the Battle of Gaugamela in Iraq (331 B.C.E.). Although Darius III’s troops outnumbered those of Alexander, each of these battles—and many others—were won by the Macedonian Greeks.

Throughout this period of slow conquest, province after province surrendered to Alexander and the Macedonian Greeks. In 332 B.C.E., Tyre and Gaza were taken in sieges, leaving the road to Egypt open, and Egypt surrendered soon afterwards.

Surrender of Judea to Alexander

At this time, Judea also switched from being a Persian province into being a Greek one, which it would remain until the Maccabee revolt in 167 B.C.E. Whether Alexander took any notice of Judea, we don’t know, but Josephus tells a story about Alexander’s visit to Jerusalem and how enthusiastic he was about seeing Jadua, the high priest, whom, he claimed, had appeared to him in a dream in Macedonia, telling how he could succeed in conquering Asia (Ant.11:325-339). Alexander then grants the Jews permission to continue worshipping as they always had. This apocryphal story, with some alterations, eventually made its way into rabbinic literature as well, though the high priest changes from Jadua to Shimon HaTzadik (b. Yoma 69a).

Conquest of Babylonia, Persia, and Media

By 331 B.C.E., Alexander had taken Babylon and Susa. In 330 B.C.E., after the Battle of the Persian Gate in which he defeated the Persian forces under General Ariobarzanes, Alexander took Persepolis, and had the city destroyed. By this time, Darius III, who had led the defeated Persian army in the Battle of Guagemela, had fallen back to the old Median capital, Ecbatana. But the officials at Ecbatana, having heard that Alexander was welcoming Persians who switched sides, assassinated him.

Artaxerxes V Bessus and the End of an Independent Persia

The leader of the conspiracy, Bessus, had himself crowned King of Persia under the name Artaxerxes V (330-329 B.C.E.), but the Persian Empire as such had already been lost. Unlike some of the other conspirators, Artaxerxes V decided to stand against the Greeks, and he led a rebellion against Alexander a year later in Bactria and was captured and executed. With that final defeat, Persia was no longer independent. If we count from Cyrus’ conquest of Media to the death of Artaxerxes V, the Achaemenid Kingdom lasted 220 years.

Throughout this period, Jews continued to live in the diaspora, in Babylonia, Persia, and Egypt, while others returned to Judah and rebuilt the homeland. With the coming of the Greeks, Judaism would enter the Hellenistic period along with the rest of the known world.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

March 12, 2017

|

Last Updated

March 16, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Rabbi Zev Farber is the Senior Editor of TheTorah.com, and a Research Fellow at the Shalom Hartman Institute's Kogod Center. He holds a Ph.D. from Emory University in Jewish Religious Cultures and Hebrew Bible, an M.A. from Hebrew University in Jewish History (biblical period), as well as ordination (yoreh yoreh) and advanced ordination (yadin yadin) from Yeshivat Chovevei Torah (YCT) Rabbinical School. He is the author of Images of Joshua in the Bible and their Reception (De Gruyter 2016) and editor (with Jacob L. Wright) of Archaeology and History of Eighth Century Judah (SBL 2018).

Essays on Related Topics: