Edit article

Edit articleSeries

The Significance of Kol Nidre: A Footnote

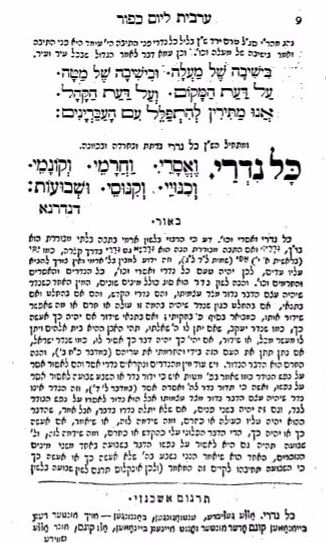

Yom Kippur Kol Nidre prayer Cantor Avraham Feintuch כל נדרי - חזן אברהם פיינטוך

_____________________

The Kol Nidre is one of the most beautiful and most peculiar prayers in all of Jewish liturgy.[1] On the Eve of Yom Kippur it captures the imagination of millions of Jews all over the world. The fact that the Eve of Yom Kippur, the holiest day in the Jewish calendar, is referred to as “Kol Nidre,” indicates its great significance.

The Meaning of Kol Nidre

But what is Kol Nidre? “All vows,” so the text says, “from this Yom Kippur until the next, may they be deemed absolved, annulled, and abandoned.” How odd, how irritating to enter the holiest day of the year with a proposition such as this! Are we setting ourselves up in advance so as to be able to break all our promises? The text is so disturbing that many traditional Machzorim immediately introduce a reassuring footnote: Don’t worry, it is not what you think!

Solutions in Footnotes

According to the fine print of the traditional “Rödelheim Machzor”, these words only concern personal vows and intentions. Kol Nidre, it explains in a footnote, is not about annulling actual promises to others, but refers only to the person who says the prayer.[2] More common is the not-much-less apologetic reading of Kol Nidre as an interaction only between man and God – as in this footnote to the prayer: “This utterance relates solely to vows made to God, and in no sense obligations entered into between man and man.”[3] At times the footnote is an actual warning: “We ask our readers not to misunderstand the meaning of this formulation.”[4]

Remarkably, the holiest moment of the Jewish year seems to begin with a footnote. This is certainly not the case in all Machzorim. But even where there is no explicitly apologetic note, there is often a great need for clarification.

In the Machzor of the Rabbinical Assembly (the rabbinic organization of the Conservative Movement), the footnote simply became part of the English translation: “All vows, renunciations, bans, oaths, formulas of obligation, pledges, and promises that we vow or promise to ourselves and to God.”[5] God, though, is actually not mentioned in the Kol Nidre.

Something here does not add up. Jews are at the conclusion of the ten Days of Awe, of teshuvah, return, of judgment and truth. The synagogue and the Torah scrolls are dressed in white, everyone is ready to fast—and then the prayer book begins with a disclaimer that the most important prayer does not really mean what it seems to say.

A Problematic Prayer Throughout Jewish History

The Kol Nidre prayer was always a riddle and the resentment it provokes is old. The earliest references to the prayer come from the geonic period (Amram, 9th century). Already then, there were attempts to abolish the prayer because of its distressing content. Scholars of the “holy academy” had called it a “foolish custom” [6](מנהג שטות). But Kol Nidre was not so easily done away with. It was instead adjusted: Where once the promises and obligations from the previous year were made void, since the 12th century according to Ashkenazi Machzorim, the promises and obligations for the following year are to be annulled. That change intended to prohibit a retroactive understanding of the prayer which was considered disturbing.[7] But the adaptation hardly makes the text easier to swallow, all the more since the past tenses of the verbs (“that we have vowed” etc.) remained unchanged. In spite of severe critique from leading authorities of Judaism Kol Nidre has stayed.

Christian accusations

Christians have taken Kol Nidre as proof for not trusting Jews swearing an oath. Thus Johann Andreas Eisenmenger states in his Entdecktes Judenthum (“Judaism Unmasked”) from 1700:

Because of such an absolution and remission of an oath, I say that Jews are accused by many of being freed from all false oaths that they swear.[8]

Eisenmenger cites Samuel Friederich Brentz (apparently a convert) who had written:

With regard to their oaths one needs to know that the Jews have a peculiar prayer in which they allow themselves to commit perjury against the Goyim, that is, against the Christians. And this prayer they say with great reverence. (…) its name is Kol Nidre.[9]

Jews were aware of these accusations and the continuing risk of Kol Nidre. Samson Raphael Hirsch, the leading voice of German orthodoxy in the 19th century, cancelled Kol Nidre during his tenure in Oldenburg, but it reentered the service after a short time.[10] Abraham Geiger, the harbinger of Reform Judaism, rephrased the text: “all my transgressions and the transgressions of this congregation (כל־פשעי ופשעי הקהל הזה): they shall be removed and made null.”[11]

This alternate version, however, did not successfully replace the original. Until today, many Reform communities still sing the Kol Nidre, albeit sometimes adjusted and freely translated. In the end Kol Nidre has persisted and remained a universal tradition up until today wherever there is a Jewish community--Orthodox, Conservative or liberal communities.

A Group Phenomenon

How did a prayer about annulling vows become so central? It seems that Kol Nidre has taken on a life of its own. The meaning of the words no longer plays an important role. But it is known that Kol Nidre has come to represent collective effervescence, when a group comes together with the same thought to perform a particular action. At no other moment during the Jewish year do so many Jews gather together. Even those who typically refrain from visiting synagogues all year, find their way to a service.

Already in antiquity, which one too often imagines as completely Orthodox, Yom Kippur managed to attract those who otherwise did not keep the commandments. The Jewish philosopher and theologian Philo of Alexandria observed that the fast day of Yom Kippur was respected not only by pious people, but also by those “who otherwise do not lead active religious lives.”[12]

Collective effervescence — as the French sociologist and son of a rabbi, Émile Durkheim (1858-1917) has shown – is a key element of religion.[13] It is in the group that Jews show solidarity and cohesion. Possibly no other religion does this so consistently through liturgy as Judaism. Jews can and will only say many prayers when they are part of a group, a minyan. Jews don’t say Kol Nidre in solitude.

Lost in the Melody and Archaic Sounding Language

Kol Nidre is tantalizing. First, the chazan sings it quietly, then louder, then increasingly louder, three times. All vows, obligations and oaths are annulled. Its language is alluring. Practically all communities recite Kol Nidre in Aramaic, not in Hebrew (with the exception of one sentence in the middle of the prayer). Even to those who do not have command of the language, it points out that something here is different, this is not the standard repertoire of Jewish liturgy.

The Kol Nidre prayer is alienating. But it is also mesmerizing. The foreign sounding Aramaic and Hebrew allows for the possibility of experiencing not just the actual meaning, but also the sound of the words and fill them with new meaning. The haunting melody of Kol Nidre is old. In the Jewish tradition it is even considered a misinai niggun: a melody from Mount Sinai.[14] Independent of content, Kol Nidre, recited and sung in a full synagogue, is a call for attention unparalleled in Jewish culture.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

October 10, 2016

|

Last Updated

November 23, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. René Bloch is Professor of Jewish Studies at the University of Bern (Switzerland), where he holds a joint appointment in the Institute of Jewish Studies and the Institute of Classics. He obtained his Ph.D. (Dr. phil.) as well as his “habilitation” from the University of Basel. Bloch’s most recent publications include: “Bringing Philo Home: Responses to Harry A. Wolfson’s Philo (1947) in the Aftermath of World War II,” “Dying in Egypt: Philo’s Joseph as a Cosmopolitan Citizen,” and “Jüdische Bibelkritik in Antike und Mittelalter: Von Philon von Alexandrien bis Spinoza.”

Essays on Related Topics: