Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Tips for the Passover Seder

123rf

Seder Night: Memory and History

Memories, old and new—Over the ages, the seder has forged memories, personal, cultural and social, and has been influenced by new memories over time. Memory does not have to entail historical accuracy. The importance is the meaning of the “memory” בְּכָל דּוֹר וָדוֹר “in every generation.” —Aren Maeir

Memory and Joseph’s Bones: Who is the Serah in your family?—According to Exodus (13:19), the last task Moses had to accomplish before leaving Egypt was to find and bring Joseph’s bones with the Israelites on their journey to the Promised Land, to fulfill the brothers’ oath (Genesis 50:25). The midrash embellishes this with a story of how Moses could not locate the bones until Serah the daughter of Asher, an ancient woman who alone survived of those who left Canaan, informs him that the Egyptians sunk Joseph’s coffer to the bottom of the Nile, whereupon Moses summons it to rise to the surface and the Israelites can leave.[1]

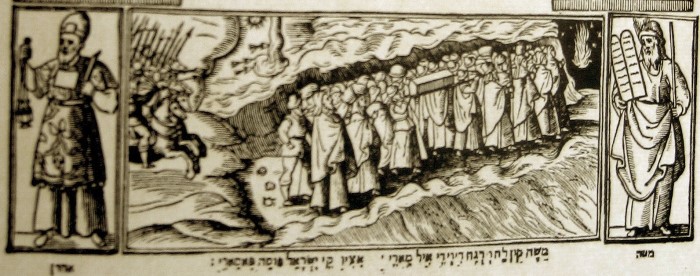

Joseph’s coffin at the center of the splitting sea. (Venice Haggadah, 1609)

Joseph’s coffin at the center of the splitting sea. (Venice Haggadah, 1609)

This should encourage each of us to wonder: Who, like Serah, is the repository of memory and continuity in your family?—Rachel Adelman

Between the seder and Thanksgiving—I would advise not associating historicity with the exodus. The story is part of our collective memory. It is similar to Thanksgiving. Only 65 people were on the Mayflower but today 330 million people celebrate as if they, or their ancestors, had been on the Mayflower. I celebrate the seder as an expression of our collective memory, and what connects me to my Judaism. Not historicity but collective memory is the glue. — Rami Arav

Reliving the story, like a movie—Though I am an archaeologist, one thing that we do not do at the seder, is talk about archaeology, history, or academic biblical scholarship. Think of movies. When we watch a movie, we are all in on the story-line of the movie. We might even pause the movie, and ask the person we might be watching the movie together with about lacunas in the plot (this is what ba'alei midrash were doing). But we are all in. We are fully engaged and voluntarily put our critical thinking aside. Why do we do this? Because that is what watching a movie is all about! If we start asking critical questions (“But how does he fly like that?”; “But how do they breathe in outer space?”; “But how did he not get shot with all those bullets flying?”) we are missing out on the entire experience of watching a good movie. And that experience can be incredibly powerful. So for us, the seder is not the time to engage with the past in a critical, scientific manner but to relive the story of the Exodus in an embodied way. We do this verbally, by retelling the narrative, but also physically by eating the foods, drinking the wine, and enacting the various rituals which over the past two millennia have developed into the seder we have today. — Yonatan Adler

National heritage and academic insights—The historical accuracy of the exodus narrative is not something I would insist on, as I see its main value as a national heritage. Nevertheless, I encourage critical questions (=those I can answer!) about the Haggadah and the Pesach narrative, so that I find myself talking about the development of midrashim or about Egyptian records of Semites coming to / leaving Egypt etc., following the interests of the family. — Ruth Fidler

Modern History

Women’s stories—One of the unique features of Pesach is that כולנו מסובין, we are all gathered together. Pesach encourages us to consider questions of inclusivity, especially of those who didn't always have a place around the table. I try to find ways to include women and women's stories, such as a passage I composed along with Tamar Duvdevani about the four daughters alongside that of the four sons.[2] — Dalia Marx

The Holocaust—“You are the third generation to follow your grandparents, who came out of the valley of death, the hell on earth called Auschwitz,” we tell our children. “They were among the small remnant, and they made the State of Israel their home. That is our exodus. Enemies have always risen up to destroy us, but never before was there a systematic enterprise for the wholesale murder of all Jews such as the Nazis devised. And none were there to save them. You too shall tell this to your sons and daughters—the fourth generation.” — Cynthia Edenburg

Aciman’s Memoir and the modern exodus from Egypt—We read selections from André Aciman, Out of Egypt: A Memoir (1994), especially the final chapter, “The Last Seder,” with his vivid description of April 1965, when the author and his family left Egypt during Passover. Aciman describes how, upon concluding the seder that evening, the extended family walked to the Corniche (the main promenade in Alexandria), for one final stroll along the Mediterranean coast. Aciman writes that even then, as a 14-year-old boy, he knew, “I would always remember this night.” And then the last line of the book, with reference to the other (i.e., non-Jewish) people out for their evening stroll, who “would never, ever know, nor even guess, that this was our last night in Alexandria.” — Gary A. Rendsburg

Born in British Mandate Palestine—I was born in Palestine, before the State of Israel was established, and I remember life under a foreign rule and the struggle for living in our own independent country. For me, the seder evening is an opportunity to bless the fact that we live in our own free country, with our children and grandchildren around our table, in spite of all the different and difficult problems our young Israeli society faces. — Yairah Amit

Haggadot

Geniza Haggadah—We like to use the Haggadah from the Cairo Geniza, representing the early liturgical customs of the land of Israel, and discuss how this differs from the Haggadah that we are used to, and how it developed over time. (As this version is missing the songs at the end, we add those back in.) — Marc Brettler & Tova Hartman

Sarayevo Haggadah—I have a replica copy of a Haggadah that survives as a relic from Spain prior to 1492, which I bought in Sarayevo in the 1970s. It is almost identical to the modern Haggadah in its text and is illustrated beautifully. — Rami Arav

Amsterdam Haggadah—Most evident are beautiful haggadot, one of the few Jewish texts that have been calligraphed and illustrated since medieval times. Our collection includes facsimiles of the Sarajevo Haggadah (late 14th century) and the Amsterdam Haggadah of 1712, The Moss Haggadah (1990), and the Passover Haggadah Graphic Novel (2019). —Adele Berlin

Goldschmidt Haggadah: History of the text—We like to review details about the development of the Haggadah from its pristine format to its present form. E. Daniel Goldschmidt’s הגדה של פסח ותולדותיה [The Passover Haggadah: Its Sources and History] is excellent for this.[3] — Emanuel Tov

Yosef Yerushalmi’s Haggadah and History is a marvelous resource for the seder. We often select pages from this photographic history of the Haggadah to illustrate how the Haggadah mirrored the history of the times in which it was written. A nice example is the depiction of the four sons as contemporary political leaders in the Arthur Szyk Haggadah from the 1930s. Hitler is obvious, but guess which one is FDR. — Steve Bayme

The Kibbutz Haggadah —Our family version of Hallel is a spring-theme sing along, continuing the kibbutz tradition of re-introducing the seasonal-agricultural aspects into Pesach. The Kibbutzim created their own Haggadot, a central example of which is that of Kibbutz Beit Hashitah, created and illustrated by David Alef in 1940, which became the official Haggadah of the movement until 1977. Alongside the traditional readings, this Haggadah, and others like it, contains narrations from the Torah as well as contemporary texts and songs, and illustrations of kibbutz life.

The spirit of the kibbutzim Haggadah is alive in my family, and allows us, as secular Jews, to celebrate the beauty and hope of springtime, and the human aspiration for freedom. — Yael Avrahami

Engaging with Art

Facsimiles—Prior to the seder, we gather facsimiles of medieval Haggadot so we can discuss their illustrations.[4] — Sara Offenberg

Show and tell—In honor of the visual learners among us, we usually devote a stretch of one seder to having each participant share the different illustrations s/he has in the Haggadah s/he has chosen, and talking about how the narrative can be variously interpreted by way of images. — Sam Fleischacker

Art as midrash—We use art throughout the ages to discuss how various generations have viewed this text, and how we, like these artists, bring our own assumptions/experiences/biases when reading a text and then interpret the text to fit into our lives (similar to what midrash does). It’s a great intro into the concept that there isn’t an “objective reading” of the passages. — Sara Tesler

Intersection of art and text—Every year, we go through a different set of illuminated Haggadot, and we discuss the intersection of art and text.

|

.jpg?alt=media&token=a23fe326-9432-40b6-aaf3-38cd8a959af9) |

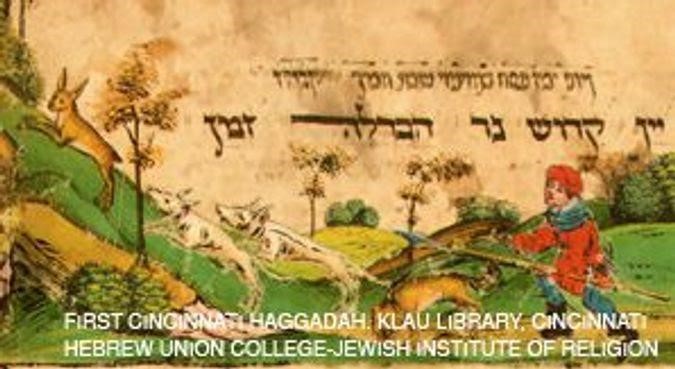

| The rabbit hunt image is meant to represent the proper order of blessings for the kiddush, called יקנה"ז (yaknehaz). This is our children’s favorite. First Cincinnati Haggadah, Germany, 1480–1490. (Klau Library, HUC-JIR). | The passage is about marror, bitter herbs, illustrated with a picture of a woman. It is a displeasing association.[5] “Tegernsee Haggadah” 15th cent. Bavaria. Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munchen. Nli.org.il |

Comparing Sephardi and Ashkenazi practices —In 2020, during COVID, we had seder with just the two of us—the kids were asleep. Each of us took a different facsimile of a Haggadah manuscript, one Sephardi and the other Ashkenazi, and compared. It didn't hurt that the marginal drawings were amazing! — Phil Lieberman & Yedida Eisenstadt

Artifacts—What makes our seder especially meaningful is not words or actions but special objects, more than just those on the seder plate. Our most precious object is a hand-made, beautifully etched silver wine cup, from my great-great-grandfather. It does not stand quite level, dented, they told us, in the 1905 Kishinev pogrom (my grandparents, with my mother and two siblings, came to America in 1906 from what is now Moldova). My grandfather drank his wine from this cup at the seders, but we use it for Elijah’s cup. Indeed, for us Pesach is a holiday of enduring objects. —Adele Berlin

Preparing for the Seder, Educational Strategies

Color-coded Haggadah art project—I wrote out the entire Haggadah on 1 huge piece of paper, 7 x 4 feet. (I needed to go to a specialty store to buy a massive roll in that size). Then each section is color coded based on the development of the Haggadah, historical additions, connection to the Talmud (shows both Rav and Shmuel’s opinions of שבח “praise” and גנאי shame). It gives the participant a “big picture” of the Haggadah instead of getting lost on the page. We hang it on the wall so everyone can follow together; the kids have stood there staring at it and can see the Haggadah as a unified intentional text. — Sara Tesler

Homework—In preparation for the seder, adults and kids are assigned to write a diary entry of someone leaving Egypt—either imagining themselves there or taking the role of someone else, famous or not. Then during the seder people share their writing at appropriate times/intervals. — Aaron Koller & Shira Hecht-Koller

Prepared questions/answers—Ask each individual or family to bring an appropriate question to the seder (preferably with an answer). — David J. Zucker

Divrei Torah—We have a series of short divrei Torah prepared for different points in the seder, especially involving visuals from Egypt or old haggadot. As these are repeated, we suspect that someday someone will remember them. — Aaron Koller & Shira Hecht-Koller

Quiz of Redemption—Before searching for the afikomen, Prof. Gary Gilbert, the host of the seder I attend, gives a multiple choice “quiz of redemption,” with all sorts of interesting little tidbits about Passover. Because they are about the history of the Jews and the development of the ritual, oddball choices are sometimes correct. It is really hard! We go over the answers together and laugh, even when we receive a very poor grade. — Tammi Schneider

Escape room—In recent years, we have been using an “escape room” type game (available commercially) during the seder. — Yigal Levin

Game show—During the meal we’ve used a Jeopardy-style game show. —Aaron Koller & Shira Hecht-Koller

Dress up—When our children were small, we went along with my uncle’s project (Dr Aharon Ellern, RIP) of dressing them up as Israelites in the Exodus. It certainly helped liven up the story for them. — Ruth Fidler

Managing expectations— Plan for a realistic length of the seder and try to ratchet down your expectations of “this year it really will be meaningful.” — David J. Zucker

Seder Plate and Foods

Real pesach lamb—I believe the Pesah was meant to be, and to remain, a home or localized offering and that we miss something palpable with only symbols. I grill a cut of lamb, place it at the center of the seder plate, and we eat it before Maggid, with the blessings for the Chag and the Pesah from the Tosefta Pesachim 10:13.[6] — David Bernat

Good sized lamb, Aleppo tradition—On the seder plate (ke`ara) set according to the ARI (Isaac Luria), pride of place is given to a good-sized lamb shank. The charoset is made from crushed date, with cinnamon, wine, and nuts. —Jack Sasson

Orange on the seder plate—I always place an orange on the seder plate. According to one version of the urban legend, this is in response to someone who asserted to Susannah Heschel that a woman belongs on the bimah as much as an orange belongs on the seder plate. — Marvin Sweeney

Seder Plate on the head, a Moroccan custom—From my (Moroccan) husband’s side, at the beginning of the seder the person leading the seder picks up the Seder Plate and holds it above the head of each participant, turning it in circles like a halo while all sing the following words: בִּבְהִילוּ יָצָאנוּ מִמִּצְרַיִם, לְשָׁנָה הַבָּאָה בִּירוּשָלָיִם “we left Egypt in a rush; next year in Jerusalem.” Someone else does it for him as well, and if someone is pregnant she gets a double reading. (The tune has 3 variants, and we use all of them in turn.) — Nili Wazana

Karpas Deluxe—We have an elaborate karpas course, following the view (Rambam, etc.) that karpas should be more than a כַּזַּיִת “an olive’s worth.” The karpas then stays out on the table throughout maggid, so no one complains about hunger. Examples of karpas dips:

- Celery dipped in salt water

- Strawberries dipped in chocolate

- Artichokes and asparagus dipped in garlic mayo

- Carrots dipped in almond butter [peanut butter for kitniyot eaters]

- Peppers dipped in guacamole

- Baby red potatoes dipped in pesto

- Bananas in chocolate spread

- Kale dipped in balsamic vinaigrette

- French fries in ketchup

- Beet chips in Caesar dressing

- Edamame in soy sauce (for kitniyot eaters)

This both allows for a minute of halakha review each year, when we look at the sources about karpas, and more importantly allows maggid to be done without pressure. — Aaron Koller & Shira Hecht-Koller

Shaping the matzah, Aleppo tradition—The middle matzah of the yaḥatz is cut into the shape of the Hebrew letters dalet (gematria value of 4) and a vav (gematria value of 6), symbolizing דוד (David), as well as the 10 plagues, 10 commandments, 10 sefirot, etc. — Jack Sasson

Biblical foods—My menu this year is foods of the Tanakh. Red Bean Stew, Egyptian style Tilapia, Salad of cuke, leek, and melon (Numbers 11), and quail, with sweets inspired by Shir HaShirim and Kamanu/Kavanu type charred cakes for/of the Queen of Heaven (per Jeremiah 7:44 and Mesopotamian evidence). — David Bernat

Afikomen slung on the shoulder, Aleppo tradition—Before reciting the haggadah: The afikomen is placed in a large cloth. It is slung over the left shoulder sequentially of each participants who recites: משׁארתם צררת בשׂמלתם על־שׁכמם ובני־ישׂראל עשׂו כדבר משׁה (Exod. 12:34 ) . Each needs to answer two questions posed in Arabic: “Where are you from?” (normally “from Egypt”) and “Where do you go?” (normally “to Jerusalem”). Kids have fun with this one. — Jack Sasson

A cane and a sash—In some Mizrahi communities, one of the children is given a cane, and a sash that is tied around the waist, as a theatrical nod to Exodus 12:11. The napkin with the afikomen is then slung over the shoulder to be carried until needed at the close of the meal. He/She is asked “Where have you come from?” Answer “From Egypt.” “And where are you going?” “To Jerusalem.” “And what do you sing on the way?” The answer is the Mah Nishtanah. — Steven Golden

Eating the shankbone, Aleppo tradition—Before the main meal, pieces from the shankbone are shared with the participants. An egg, dipped in saltwater is eaten by each, זכר לקרבן חגיגה “in memory of the chagigah offering” —Jack Sasson

The Golden Kneidlach—My sister always makes the kneidlach (matzah balls) and puts something sweet in one of them, a piece of raisin, a piece of a beet, etc. Whoever finds it wins a reward, usually a box of chocolates. (We look forward to this the entire year.) — Shlomit Bechar

Mah Nishtana Alternatives

Polyglot—We have people say Mah Nishtana in any language they’re even passingly familiar with. This year I think we have Arabic, Italian, French, Aramaic, Yiddish, and Latin represented.[7]— Aaron Koller & Shira Hecht-Koller

The Three Questions—Along with the regular Mah Nishtana, the four questions recited by the youngest child who can, we have someone else sing what seems to be the original Mah Nishtana, the three questions, about dipping twice, only matzah, and roasted meat.[8] The answers are found in the passage later in the haggadah, in which Rabban Gamaliel states that on this night we need to speak of the three mitzvot, the paschal lamb (answering question 3), the matzah (answering question 2), and marror (answering question 1). — Zev Farber

The Five Questions—We use the Mishnah manuscript from the Cairo Genizah, which has the regular four questions everyone says, plus the one about meat.[9] — Aaron Koller & Shira Hecht-Koller

Questioning the questions—After reading the four questions, I like to ask people at the table what they mean? Think about all of them, it’s not so easy to explain them! — Emanuel Tov

Thought Questions on the Haggadah

I like asking thought questions. Here are some favorites:

- How are the four cups used as a structuring device for the Seder?

- What are the three stages in the transformation of the meaning of the matzah as the Seder progresses?

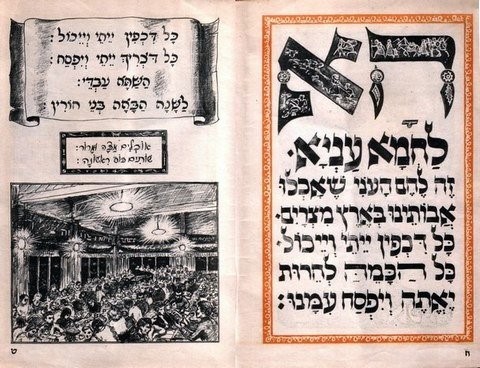

- How many interpretations of הָא לַחְמָא עַנְיָא are plausible?

- Is the Aramaic of the Haggadah such as הָא לַחְמָא עַנְיָא and that found in אֶחָד מִי יוֹדֵעַ to enhance understanding or to enhance the rhyme scheme?

- Which is the better way to begin with degradation and end with exaltation, the Moses centered: “we were slaves in Egypt” or the Abraham centered “our ancestors were worshippers of foreign gods”? Or, put another way, what is the greater Jewish revolution: from polytheism to monotheism, or from slavery to freedom?

- How many aspects of the Haggadah can be subsumed under the rubric from slavery to freedom?

- Do the four children represent moral types or intellectual types? What is the relationship between them?

- Why is the role of Moses virtually eliminated from the Haggadah. Is this comparable to the elimination of his role in the Song at the Sea? Is it like the elimination of Nebuchadnezzar from Eichah and the downplaying of David in the Amidah?

Maggid, Telling the Story

Gomel—It has been a rough few years. This year, our first all-around-the-table seder in four years, we'll begin by reciting gomel, the blessing thanking God for preserving our lives. — Fran Snyder

Parent-child retelling—Before maggid, we pause and one by one, each parent tells the story of Pesach to his/her children adjusted to their age. The older grandchildren may turn their historical questions to grandpa. I got the idea from my rabbi, Rabbi Shlomo Riskin. — Dudu Cohen

Women’s participation—Much of the procedure for Seder Night is equally incumbent on women as men; Sefer ha-Hinukh (some others disagree) maintains that this includes the mitzva of וְהִגַּדְתָּ לְבִנְךָ “and you shall tell your child” (Exod 13:8). Thus, we involve women equally with men in all the readings and rituals of the Seder. — Norman Solomon

Everybody reads—We appoint a master, or more often mistress, of ceremonies, for organizing the Seder. The haggadah is read piece by piece by each person at the seder, including children, according to their order of sitting at the table (apart from the Ma Nishtana, reserved for all children present together). — Athalya Brenner-Idan

Freedom—Reflecting on the statement that we would still be slaves in Egypt, I ask each person to reflect on what freedom means to them. In what way are we free today and in what way are we not? — David Steinberg

Personal answers—We break up into transgenerational chevrutot (or small groups) and give our own, personal answers to the questions of the four children. — Elsie Stern

Reading Exodus—On the second night, instead of reciting the Maggid, we tell the story of the exodus, something that the Haggadah forgets to do, with special attention to Exodus 12. — Shaye J.D Cohen. My father also had this custom, which we continue. —Naomi Koltun-Fromm

Slavery in Joseph’s Time—The Haggadah focuses on Israel’s bondage in Egypt, beginning with Exodus 1, but when we look earlier in Genesis, we can see that its seeds are in the Joseph story, when Joseph enslaves the Egyptians. Already, in this story, Joseph must request permission to leave, and the family seems to be stuck in Egypt. I like to talk about this backstory and consider what it means. — Philip Kahn

Sitting elsewhere—For maggid, we move away from the table and recline comfortably on the couches to tell the story. It is more natural for conversation and removes the food pressure. — David Bar-Cohn

Compare commentaries—Since different people have different Haggadot with different commentaries, this sometimes leads to discussion. — Yigal Levin

Arabic recitation—In Halab [Aleppo] and Beirut, several sections of the Haggadah were repeated in Arabic—almost always at least the הא לחמא עניא (“this is the bread of affliction”) and עבדים היינו לפרעה (“we were slaves to Pharaoh”) —Jack Sasson

Humor—I like to include humor, especially from my late father, Rabbi Abraham Kellner z”l. On the passage יָכוֹל מֵראשׁ חֹדֶשׁ, which discusses whether the story of the exodus should be told to the child at the beginning of the month, on the day before the seder, or on the seder itself, he used to say that this passage relates to how rabbis would post sources for their Shabbat ha-Hagadol lectures. Those who were capable scholars would post them early; those who only repeated what they had learned would post them that morning, and those who truly had nothing to say would only announce them at the lecture itself. — Menachem Kellner

Reflections on Arami Oved Avi

Not the Plain Meaning—The Haggadah departs from the plain meaning of the biblical text. Perhaps the most significant example is אֲרַמִּי אֹבֵד אָבִי (arami oved avi, Deut 26:5) which in the Torah means “my father (=Jacob) was a wandering Aramean,” but in rabbinic midrash is understand as “an Aramean (=Laban) tried to kill my father (=Jacob), an embellishment of the story that is absent from the Torah.[10] — Jonathan Ben-Dov

Influence of Aramaic—The rabbis rereading doesn’t work in biblical Hebrew, where oved means “wanderer” or “nomad.” The translation “destroy” would only suggest itself to speakers of Aramaic, like the rabbis. — Rami Arav

Pro-Egypt, anti-Syria Polemic—Why do the rabbis re-read this passage to claim Laban as having been more murderous than Pharaoh – he wanted to “eradicate everyone,” not just first-born Israelites. Louis Finkelstein suggests that Laban represents Seleucid Syria, during the period of its rivalry with Ptolemaic Egypt over control of the Land of Israel.[11] If so, this would make this a political, pro-Egyptian midrash and one of the oldest in the Haggadah, dating from the 3rd century B.C.E.— Mordechai Cogan

Demonization—We discuss the problem of demonization, in the light of the rabbis re-reading of this text, which makes Laban out to be much worse than in the Torah.[12] — Naomi Graetz

The Biblical Verses in Maggid

Responsive derashot—For the “go forth and learn” derashot, we have one person read the verse from the Torah and another the derashot, which depicts in a concrete way how the rabbis are rereading the verses which originally mean something else. — Zev Farber

Beginning and ending in Israel—The story of Israel’s exile in Egypt and the exodus are told according to a narrative pattern that is widespread in the ancient Near East and in the Bible. A hero is compelled to go into exile; during the exile a deity assures the hero that he/she/they can return home; the return is beset by troubles; but the hero returns home to a respectable position and founds or renews a cult, acknowledging the deity’s support.[13] What this means for the story of Israel is that the exodus begins and ends in the Land of Israel—from the life of Jacob in Canaan through the resettlement of Canaan after the exodus. — Ed Greenstein

Free will—Maimonides’ Haggadah text lacks the derasha:

וַיֵּרֶד מִצְרַיְמָה – אָנוּס עַל פִּי הַדִּבּוּר.

“He went down to Egypt”—forced by the word [of God].

In his commentary on the Haggadah, called Zevah Pesah, Isaac Abravanel asked why Rambam’s text lacks this text, and answers that Maimonides could not have included those words since he held that free will was a great ikkar, a pillar of the Torah, and a fundamental teaching of Judaism.[14] The answer shows that Abravanel was an honest (if often annoyed) reader of Maimonides. — Menachem Kellner

The 10 Plagues and 250 Plagues

Choose your plague—Each person at the table picks a plague and describes what they imagine it felt like. Another way to do this is through charades. — David Steinberg

The Abbreviations: Humor—My father asked: Why did R Yehudah use the abbreviations דְּצַ"ךְ עַדַ"שׁ בְּאַחַ"ב for the 10 plagues? He answered with a story: As a young man, R. Yehudah could not afford to go home from yeshiva for Pesach and was farmed out for the seder to a notoriously stingy member of the community. When the baʿal habayit (householder) asked why R. Yehudah was using abbreviations instead of the full list, R. Yehudah explained that if he took a drop out of his cup of wine for each plague, he would not be left with enough wine on which to make a blessing. — Menachem Kellner

Only ten plagues—The ten plagues are biblical, but what is being taught by listing them? Perhaps the list, as well as R. Yehudah’s mnemonic, דְּצַ"ךְ עַדַ"שׁ בְּאַחַ"ב, are meant as a polemic against those midrashim that multiply the number of plagues. At our seder, we do not recite the 50/200/250 midrashim.[15] — Steven Golden

Sages one-upping each other—Puzzling out what’s behind the midrashic selections included in the first half of the Haggadah can engage every seder participant. An easy one to decipher is the “I can do you one better” competition between the Sages, who calculated the number of punishments brought upon the Egyptians at the Sea of Reeds – 50, 200, 250. All incredibly high and very unreal! — Mordechai Cogan

Describing new plagues—My son-in-law brought us a custom from his family. When reading about how the rabbis expanded the plagues to include 50, 200, and then 250, each person at the table has to suggest their own expansion. Over the years, some examples have been the plague of constant sneezing, the plague having to speak backwards, and the plague of having an unlimited supply of very good jellybeans (think of the stomach aches). — Zev Farber

End of Maggid

Triptych Symbolism—When we arrive at the part explaining why we eat pesach, matzah, and marror, we depict Miriam as the bitter marror, Moshe the leader as Matzah, and Aaron the priest as Pesach.[16] — Naomi Graetz

Blessings for redemption past and future—While our Haggadot generally print the conclusion of maggid as if it were one long blessing, it is really two. The first is:

...אֲשֶׁר גְּאָלָנוּ וְגָאַל אֶת־אֲבוֹתֵינוּ מִמִּצְרַיִם, וְהִגִּיעָנוּ הַלַּיְלָה הַזֶּה לֶאֱכָל־בּוֹ מַצָּה וּמָרוֹר.

…who redeemed us and redeemed our ancestors from Egypt, and brought us to this night to each matzah and marror.

The second begins,

כֵּן ה' אֱלֹהֵינוּ וֵאלֹהֵי אֲבוֹתֵינוּ יַגִּיעֵנוּ לְמוֹעֲדִים וְלִרְגָלִים אֲחֵרִים הַבָּאִים לִקְרָאתֵנוּ לְשָׁלוֹם...

So shall the LORD our God and God of our fathers bring us to other holidays and festivals that shall come upon us in peace…

Both blessings appear in Mishnah Pesachim 10:6. The first is that of Rabbi Tarfon, and it concentrates on the present. The second is that of Rabbi Akiva, and it concentrates on the messianic future (and the rebuilding of the Temple). While they are combined here, they express different conceptions of the Seder and, furthermore, of the meaning of Redemption. To emphasize this, I pause after completing the first before continuing with the second. — Ishay Rosen-Zvi

The End of the Seder

Protecting the home with Afikomen, a Transylvanian custom—Following the meal, we break the afikomen, wrap a piece of it in a napkin, and place it behind the mirror until it is disposed of (together with a single hamantash to be kept specifically for that) in the next years burning of chametz. Keeping the afikomen is supposed to a segulah to protect the house. The custom comes from my grandfather’s home in Transylvania before the Holocaust. — Sara Offenberg

No spilling of wrath—I do not say the passage, שְׁפֹךְ חֲמָתְךָ אֶל־הַגּוֹיִם אֲשֶׁר לֹא יְדָעוּךָ “pour out your wrath on the nations who know you not” (Jer 10:25 [=Ps 89:6–7]). I understand the cathartic value of the passage in times of great persecution, but in our day, I consider it morally wrong as well as educationally unsound to recite this passage at the seder. — Zev Farber

Not in keeping with the seder’s spirit—We did not include this in our Haggadah, as Hakham Isaac Sassoon explains in his introduction to the siddur, “Shefokh very likely owes its formal absorption into the ashkenazic rite to… unspeakable tragedy and a very specific type of culturally-conditioned reaction. In any case, shefokh seems extraneous to hazal’s Haggadah which narrates the Exodus story and gives thanks. Calling down vengeance, whether on Egyptians or any other enemies past or present, jars with their seder.”[17] — Steven Golden

The Great Hallel—We recite Psalm 136, known in Jewish tradition as “the Great Hallel,” responsively, with one leader reciting the variable halves of each verse and the rest of the celebrants responding with the fixed refrain at the end of each verse, כִּי לְעוֹלָם חַסְדּוֹ, “His steadfast love endures forever.” This is likely how it was originally recited in biblical times. — Shalom Holtz

The fifth cup—In our family we do a fifth cup. Thus, at the end of the second part of Hallel, we say the blessing on the wine and drink. Then we do so again after Hallel HaGadol. We started doing this for Soviet Jewry in the 1970s, but it also seems to be how the Haggadah is actually set up, with a cup of wine after each praise section.[18] — Edwin Farber

The Songs

Arabic “Who Knows One,” Aleppo tradition—Among the songs sang toward the end is one in Arabic, min yi`lam wamin yidri ("Who might know and explain"?) giving a count from one to 13, in increasing tempo (my sister was a whiz on that one). Differences: for 2, Moses and Aaron; 7, blessings for wedding; 13, bar mitzvah.—Jack Sasson

Animal noises—My wife likes to have each person make the appropriate noise in Chad Gadya: goat, cat, burning stick, etc., as each character appears in the song. — Edwin Farber

Correcting the goat’s grammar—The late Professor Moshe Goshen [Professor of Semitic Languages at the Hebrew University, among other credentials] once toyed with the idea of asking an Aramaic expert to produce a normative version of Chad Gadya based on proper Aramaic grammar. Any takers? — Jonathan Ben-Dov

Warsaw Yiddish song—Our family custom, from the Warsaw (Wurtzelman) side, is to end the seder with a Yiddish song similar to Chad Gadya, called Der Eppel Vil Nisht Fallt “The Apple Won’t Fall.” My mother would also throw crumbled matzah at everyone afterwards, I was never sure why (to simulate the apple falling at the end?). Certainly the kids always love that part, and stay up till the end to do it. — Edwin Farber

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

April 4, 2023

|

Last Updated

October 9, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Staff Editors — Every essay published on TheTorah.com undergoes multiple rounds of editing by at least three part- or full-time editors. This process ensures that the scholarship is accessible to a broad readership while preserving academic rigor. Our editors help shape the narrative arc, incorporate primary sources in Hebrew and English, and maintain consistency of style across the site. A Staff Editors attribution may indicate an essay based on an author’s work, co-authored with our staff, or written entirely in-house. To see our editorial team, visit academictorah.org.

Essays on Related Topics: