Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Tzaraat as Cancer

123rf

A Medical Explanation of Tzaraat Not Leprosy

Scholars have long recognized that the King James translation of tzara’at as leprosy (Hansen’s disease),[1] which derives from the LXX’s Greek term lepra (meaning “scaly or rough skin”), is implausible.[2]

Leprosy is generally a scarring illness that leaves the victim permanently disfigured. The symptoms of Hansen’s disease differ radically from those of tzara’at. This contrasts sharply with the picture drawn in the parasha in which a person with tzaraat could achieve a complete remission and re-enter the camp without any residual evidence of the antecedent skin condition.

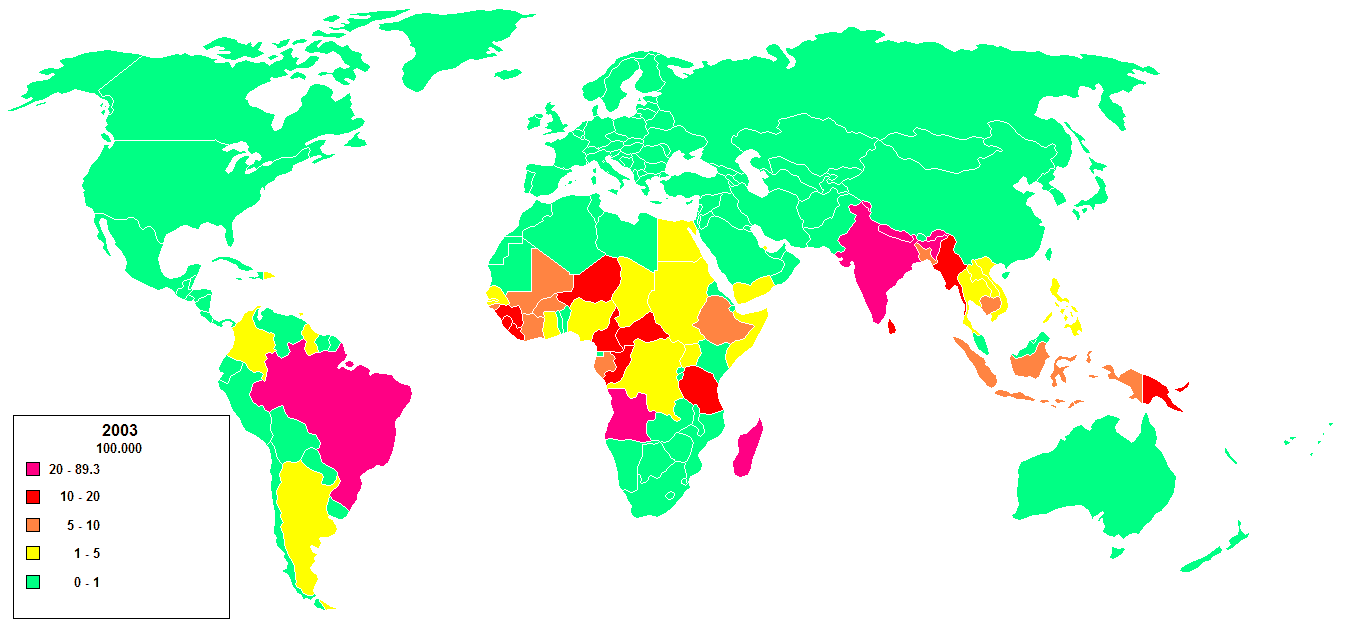

The global epidemiology of Hansen’s disease suggests that its incidence in most of the Middle East is close to zero, thus ancient Israelites would not have encountered it. This is especially true since recent studies suggest that leprosy was only introduced to the Middle East with in the last 2,000 years.[3]

Melanoma

I suggest that the symptoms of biblical tzaraat fit melanoma, a serious form of skin cancer. This is based on three key features:

- In a warm climate with a high degree of exposure to sunlight, melanoma should have been fairly common; the high ambient sun exposure in this region would have put Israelites at substantial risk of skin cancer.[4]

- Melanoma is a very serious condition with a high mortality rate, which would have provoked dread.[5] It is likely that anyone who thought he or she was afflicted would have sought “medical” help and followed through with any therapeutic plan. As Siddartha Mukhergee demonstrates in The Emperor of all Maladies, the ancients were familiar with cancer and recognized its lethality.[6]

- Melanoma can be treated, and current immunotherapy can achieve a complete remission in patients with metastatic disease without surgical intervention and, thus, no permanent physical scar. Although a favorable outcome for patients with melanoma using treatments available three millennia ago was probably rare, the verses that describe the purification of the metzora, the one afflicted with tzaraat, take for granted the possibility of complete remission without any residual damage.

Diagnosing Melanoma Then and Now

Medically, melanoma is often described by the acronym, ABCDE:

A, Asymmetric skin lesion

B, Border of the lesion is irregular

C, multiple Colors are a common aspect of melanoma

D, lesions larger than 6 mm in Diameter are more likely to be melanomas

E, melanomas Enlarge or Evolve in appearance over time or can be Elevated

While one is hard-pressed to make complete sense in medical terms of the description of tzaraat as it is presented in the text of Leviticus, many of these characteristics feature prominently in the description of the skin problem in Leviticus 13, a condition that warranted intense scrutiny.

- Asymettric (A) – Tzaraat can assume the irregular shape of a swelling (שאת), scab (ספחת) or bright spot (בהרת; 2).

- Border (B) -The lesion could look like the scar of a burn (צרבת המכוה; verse 28), suggesting that the border was not smooth.

- Colors (C) – Tzaraat is described as white (לבנה; v. 4) or somewhat reddish (אדמדמת; v. 19).

- Colored hairs (C) – The hairs ranging in color from black to yellow to white is consistent with melanocytes being the cell of origin of the lesion. (Melanocytes are derived from stem cells that reside at the base of the hair follicle and produce the pigment that is incorporated into the skin and hair. Malignant transformation of melanocytes is the pathophysiological basis of melanoma.)

- Size (D) – There is no size criterion in chapter 13 (so no correspondence on this account but no contradiction either necessarily).

- Elevated (E) – Although the text does not describe elevated lesions, tzaraat was not flush with the skin and initially was depressed, either deep (עמוק; v. 4) or lower (שפל; 20), than the surface of the skin.

- Evolve (E) – Tzaraat could evolve over time and either spread (פרחת) or recede in intensity (כהה; v. 21).

The kohen (priest) documented serial changes in the size, shape, inflammation, and hair color of the lesion and based his disposition of the metzora based on these findings.

The Quarantine

The need to quarantine the metzora (person suffering from tzaraat) during the evaluation period, and banishment from the camp if specific criteria were met, might justifiably be taken as evidence in support of an infectious cause for tzaraat, a condition that was considered contagious. Melanoma, like all cancers, is not communicable and does not require isolation. Nevertheless, the need for quarantine may not be out of fear for bystanders contracting the illness (note that the kohen does not seem to be worried about himself when he examines the person’s skin). Rather, it may be based on the perception that the sufferer was tame’ (impure) and that his or her presence was therefore disruptive to the holiness (kedusha) of the camp/village/city.

The Kohen’s Treatment of Melanoma

It is worth noting that under no circumstances does the kohen excise the lesion. This is significant since surgery is not appropriate for patients with advanced metastatic disease (it is the standard of care for lower stage melanoma, but that is not what the Torah is describing). Instead, the kohen watches the cancer and offers hope for remission in the future, which is consistent with current standard of care for patients with disseminated melanoma, namely modulation of the immune system.[7]

Stated differently, all conditions can have rare spontaneous remissions. If the immune system is responsible for controlling melanoma and checkpoint inhibitor therapy potentiates the response, it is plausible, albeit rare, that melanoma could regress on its own, which is the best that could have been expected in ancient times.

Caveat: Ancient Versus Modern Diagnostic Criteria

A note of caution is warranted when reading modern medicine into tzaraat. Just as the Torah is not a history text by modern standards, it would be anachronistic to apply current diagnostic categories in defining the nature of tzaraat. The ancients were excellent empirical scientists and accurately described many diseases such as diabetes, venereal disease, and gout.[8] However, their theoretical framework and etiological explanations are worlds apart from our understanding of disease. The kohen was not a subspecialist in oncology or infectious disease. Modern notions of contagiousness, infection, and cancer cannot be superimposed on theories of disease that were current in the ancient Near East. Nevertheless, I want to apply our ideas about disease to the parasha and find meaning for us.

A Theological Explanation of Tzaraat as Cancer versus Infection

Like all cancers, melanoma originates from a specific cell, the melanocyte, which has escaped normal controls on proliferation (called “clonal expansion”). It is the cumulative result of genetic risk-factors and lifelong environmental exposures. As a doctor, I do not bring in higher powers into consideration nor do I attribute fault to the patient with melanoma. What about the Torah?

Survey of Peshat Explanations

The text in Tazria does not associate tzaraat with sin. Many contemporary scholars emphasize this fact, highlighting that the absence of a causative sin is consistent with other components of the Priestly material in Leviticus, in which the conditions causing impurity are seen as coming from God, and are part of the natural order.[9]

Moreover, Yitzhaq Feder has emphasized Leviticus’ treatment of tzara’at is part of a broader polemic in which the priests were trying to wean the people away from a pagan view of nature, to counter the notion that impure states imply sinfulness. By so doing, their pedagogical objective was to curtail the reliance on magical practices that people would adopt to protect themselves against illness and disaster.[10]

Rabbinic Interpretation: Lashon Ha-Ra

Nonetheless, based on the text in Deuteronomy 24 in which the management of tzaraat by the kohen is juxtaposed to the command to remember what happened to Miriam—recalling the account in Numbers 11 in which she is afflicted with tzaraat for slandering Moses—the rabbinic consensus is that tzaraat is penalty for slander (motzei shem ra):[11]

דברים כד:ח הִשָּׁ֧מֶר בְּנֶֽגַע־הַצָּרַ֛עַת לִשְׁמֹ֥ר מְאֹ֖ד וְלַעֲשׂ֑וֹת כְּכֹל֩ אֲשֶׁר־יוֹר֨וּ אֶתְכֶ֜ם הַכֹּהֲנִ֧ים הַלְוִיִּ֛ם כַּאֲשֶׁ֥ר צִוִּיתִ֖ם תִּשְׁמְר֥וּ לַעֲשֽׂוֹת: כד:טזָכ֕וֹר אֵ֧ת אֲשֶׁר־עָשָׂ֛ה יְקֹוָ֥ק אֱלֹהֶ֖יךָ לְמִרְיָ֑ם בַּדֶּ֖רֶךְ בְּצֵאתְכֶ֥ם מִמִּצְרָֽיִם:

Deut 24:8 In cases of a skin affection be most careful to do exactly as the Levitical priests instruct you. Take care to do as I have commanded them. 24:9 Remember what Yhwh your God did to Miriam on the journey after you left Egypt.

Maimonides unequivocally articulates this relationship: “All agree that leprosy is a punishment for slander” (Guide to the Perplexed III:47).

Rethinking the Cause and Effect of Lashon Hara and Tzaraat

However, just as we need to rethink that the skin condition known as tzaraat is leprosy, we need to rethink its rabbinic association with slander. Without minimizing the importance of slander, lashon hara (think of how quiet Shabbat lunches would be if we took it seriously), it is important to look at the Bible’s understanding of the relations between afflictions and sins.

In places, the Bible recognizes physical affliction as a punishment for sin. The case of Miriam, discussed above, is a prime example. This is seen as well in King Uziah’s affliction as described in 2 Chron 26:19:

דברי הימים ב כו:יז וַיָּבֹ֥א אַחֲרָ֖יו עֲזַרְיָ֣הוּ הַכֹּהֵ֑ן וְעִמּ֞וֹ כֹּהֲנִ֧ים׀ לַי-הֹוָ֛ה שְׁמוֹנִ֖ים בְּנֵי חָֽיִל: כו:יח וַיַּעַמְד֞וּ עַל עֻזִּיָּ֣הוּ הַמֶּ֗לֶךְ וַיֹּ֤אמְרוּ לוֹ֙ לֹא לְךָ֣ עֻזִּיָּ֗הוּ לְהַקְטִיר֙ לַֽי-הֹוָ֔ה כִּ֣י לַכֹּהֲנִ֧ים בְּנֵי אַהֲרֹ֛ן הַמְקֻדָּשִׁ֖ים לְהַקְטִ֑יר צֵ֤א מִן הַמִּקְדָּשׁ֙ כִּ֣י מָעַ֔לְתָּ וְלֹֽא לְךָ֥ לְכָב֖וֹד מֵיְ-הֹוָ֥ה אֱלֹהִֽים: כו:יט וַיִּזְעַף֙ עֻזִּיָּ֔הוּ וּבְיָד֥וֹ מִקְטֶ֖רֶת לְהַקְטִ֑יר וּבְזַעְפּ֣וֹ עִם הַכֹּהֲנִ֗ים וְ֠הַצָּרַעַת זָרְחָ֨ה בְמִצְח֜וֹ לִפְנֵ֤י הַכֹּֽהֲנִים֙ בְּבֵ֣ית יְ-הֹוָ֔ה מֵעַ֖ל לְמִזְבַּ֥ח הַקְּטֹֽרֶת: כו:כ וַיִּ֣פֶן אֵלָ֡יו עֲזַרְיָהוּ֩ כֹהֵ֨ן הָרֹ֜אשׁ וְכָל־הַכֹּהֲנִ֗ים וְהִנֵּה ה֤וּא מְצֹרָע֙ בְּמִצְח֔וֹ וַיַּבְהִל֖וּהוּ מִשָּׁ֑ם וְגַם הוּא֙ נִדְחַ֣ף לָצֵ֔את כִּ֥י נִגְּע֖וֹ יְ-הֹוָֽה: כו:כא וַיְהִי֩ עֻזִּיָּ֨הוּ הַמֶּ֜לֶךְ מְצֹרָ֣ע׀ עַד י֣וֹם מוֹת֗וֹ וַיֵּ֜שֶׁב בֵּ֤ית החפשות הַֽחָפְשִׁית֙ מְצֹרָ֔ע כִּ֥י נִגְזַ֖ר מִבֵּ֣ית יְ-הֹוָ֑ה…

2 Chron 26:17 The priest Azariah, with eighty other brave priests of Yhwh, followed him (=King Uzziah) in[to the Temple] 26:18 and, confronting King Uzziah, said to him, “It is not for you, Uzziah, to offer incense to Yhwh, but for the Aaronite priests, who have been consecrated, to offer incense. Get out of the Sanctuary, for you have trespassed; there will be no glory in it for you from Yhwh God.” 26:19Uzziah, holding the censer and ready to burn incense, got angry; but as he got angry with the priests, tzaraat broke out on his forehead in front of the priests in the House of Yhwh beside the incense altar. 26:20 When the chief priest Azariah and all the other priests looked at him, his forehead was inflicted with tzaraat, so they rushed him out of there; he too made haste to get out, for Yhwh had struck him with a plague. 26:21 King Uzziah was a metzorauntil the day of his death. He lived in isolated quarters as a leper, for he was cut off from the House of Yhwh…

Although the Bible often understands illness as a key component of divine retribution, it never links a particular punishment to a single sin. The great rebukes (tochachot) in Leviticus 26 and Deuteronomy 28 catalogue horrible afflictions, but nowhere suggest one-to-one correspondence between illness to transgression.

Implications of Tzaraat as Cancer: A Torah Perspective with a Modern Twist

We instinctively recognize that it is wrong to blame any affliction on a specific sin. Consider for example, the revulsion we feel when people attribute the Holocaust to faulty mezuzot or assimilation. Our revulsion derives in part from the demystification of disease in modern society as a result of our ever-improving scientific understanding of the pathogenesis of nearly all medical conditions. That being said, what might be the implications of viewingtzaraat as an infection versus cancer, namely melanoma?

The Pathogenesis of Infectious diseases Versus Cancer

Infectious diseases such as pneumonia, septic arthritis, or encephalitis are caused by discrete agents that are usually external to the person. They can be bacterial (S. pneumonia), viral (West Nile), fungal (Candida) or protozoan (Trypanosome). There is an identifiable culprit(s) for the clinical condition. In contrast, cancer is an internal biological process that arises from abnormal cell proliferation, the very basis of life itself. Normal cell division for growth and adequate replacement of senescent cells is essential for body homeostasis.

There are numerous overlapping systems in place to ensure a proper balance between cell proliferation, growth, and death in all body organs (including cell cycle regulators and tumor suppressor genes). Cancer represents a breakdown in which proliferation becomes autonomous and unchecked. Cancer reflects a complex interaction between genetic susceptibility factors, environmental triggers, and disease modifiers. In truth, this applies to all disease.

How should we apply this shift in the understanding of tzaraat, from infection to cancer? All of us, myself included, are uncomfortable saying that a person got cancer, or any illness—because he or she committed such-and-such sin. This is especially the case in circumstances where it is inconceivable that there can be any fault, such as the diagnosis of leukemia in a toddler. Nevertheless, for many of us, our religious point of view makes it difficult to accept that what happens in the world is random or determined entirely by material forces.

Two Models of How to Think about Tzaraat Theologically

The classic view of tzaraat as an infection (leprosy) as a punishment for slander, lashon hara, fosters the worldview that a specific disease is punishment for a particular sin (Model 1). Outsiders may feel empowered to interpret the “religious” significance of other people’s suffering. They may harshly interpret the illness as a punishment for the other’s moral failing.[12] People who become sick may then be subject to public scrutiny and held responsible for their condition. They may become isolated because of social concerns about moral “contagiousness” or “impurity.” This only adds emotional pain to their physical suffering. Such a view of sin and punishment, lacking any compassion, was evident, with great harm, in the early years of the HIV epidemic.

A different way of thinking about God’s role comes from viewing tzaraat as a form of cancer. Cancer is an illness tied to the way we are all internally wired to survive. Since it comes from internal issues (abnormal cell proliferation) instead of external sources (e.g., contagious bacteria), it can inspire private introspection (Model 2). Rambam describes tzaraat is an אות ופלא, “a sign and wonder” amongst Israel (Mishneh Torah, Laws of Leprosy 16:10).[13]

Balancing the Two Biblical Models

Model 1 is consistent with the non-priestly texts, like the Miriam and Uzziah stories, which link tzaraat to a specific transgression. In contrast, the Priestly code in Leviticus, in which tzaraat is viewed as part of the natural order that originates with God, is more consistent with Model 2.

Human suffering, unfortunately, comes in many forms, including illness. As in much of Jewish thought, we encounter two conflicting world views about the origin of illness and suffering, and we are challenged to find a balance between them. Navigating safe passage between these two models may provide an approach to illness and suffering that enables a religious consciousness to embrace modern sensitivities.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

April 13, 2016

|

Last Updated

March 12, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Chaim Trachtman is an adjunct professor of pediatrics at the University of Michigan. He is on the board of Yeshivat Maharat and is editor of Women and Men in Communal Prayer: Halakhic Perspectives (KTAV, 2010).

Essays on Related Topics: