Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Why the Bible Is Mute about Qos, the Edomite God

Head of a horned goddess from Horvat Qitmit (probably Qos’ consort wife), now at the Israel Museum. Wikimedia adapted.

The Edomites appear often in the Bible. Moreover, the Torah describes Esau, Jacob’s twin brother, as עֵשָׂו אֲבִי אֱדוֹם “Esau the ancestor of the Edomites” (Gen 36:43).[1] And yet, the Bible says nothing, positive or negative, about Edomite religion, and never mentions their god, Qos/Qaus (קוס; the pronunciation is debated and may have changed over time).

This stands in contrast to the Moabite deity Kemosh, the Ammonite deity Molech/Milkom, the (Midianite?) deity Baʿal-peor, and the Canaanite deities Baʿal (=Adad) and Ashtoret, all of whom are mentioned in the Bible. Is this just a mere coincidence or are the biblical scribes purposefully avoiding Qos?

Qos in Epigraphy and Archaeology: A Short History

The name Qos is first attested in Egyptian temple inscriptions dating to the late Bronze Age, in names like qśrʿ , meaning “Qos protects / is my Shepherd, Friend,” parallel to biblical רעואל Reʿuel, “El is a Friend.” Another such name qśnrm “Qos is Exalted,” and there are others, though the exact reading and meaning is debated. These names probably indicate Edomite tribal groups bearing this name, if not worshipping this deity.[2]

Starting in the eighth century B.C.E., inscriptions mention Qos as the patron deity of the Edomite people,[3] and attest Edomite personal names that contain this deity’s name; this is especially true of Edomite kings and officials. For example, two Edomite kings mentioned by Assyrian inscriptions, Qausmalak “Qaus is King” and Qausgabri “Qaus is Mighty,” contain the theophoric element Qos. Qausgabri is most likely the same “Qwsgbr the king of Edom” mentioned in a bulla found at Edom.

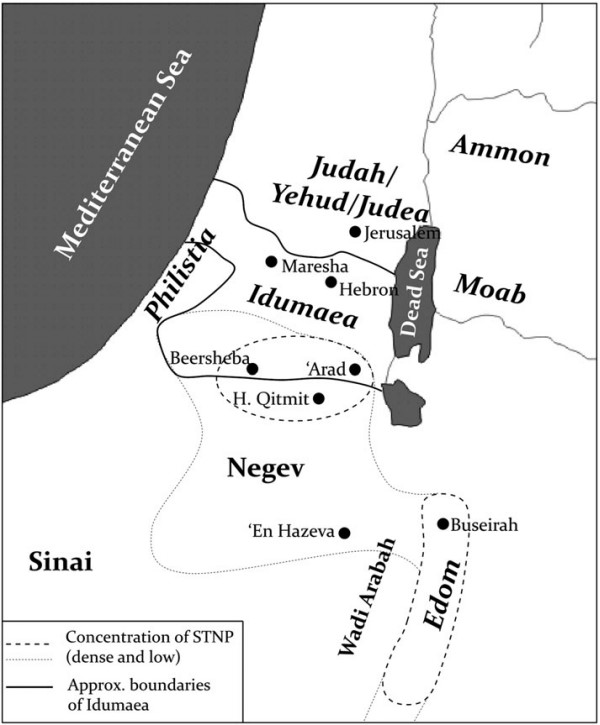

Qos/Qaus was worshipped in the Judaean Negev during the 7th–6th centuries B.C.E., a period which saw strong social and commercial links between the Negev and Edom.[4] The name Qos/Qaus appears in a short epigraphic text found at Horvat ‘Uza, where we find the phrase והברכתך לקוס “and I bless you by Qos.”[5] The name is also found in Horvat Qitmit, an open-air shrine most likely devoted to this deity, where there are two similar broken לקוס (“by Qos”) phrases.[6] These may be the oldest references to the deity not in a personal name. Another open-air shrine was excavated at ‘En Hazeva in the northern Arabah, though the evidence for this as an Edomite shrine is inconclusive.

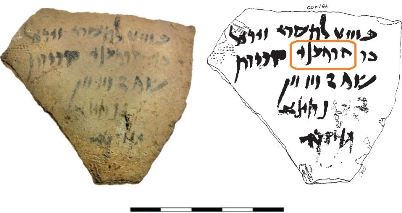

A receipt for barley written on an Idumaean ostracon from Horvat Nahal Yatir. It reads: ב5 לתשרי זידאל בר קוסעני קודות ש ס 26 [...] נתינא מנקדה “On the 5th of Tishrei, Zaydiʾel son of Qosʿany [=Qos answers], in possession. B(arley), 26 s(eah). [...] Netynaʾ Maqqedah.”[8]

During the Persian and Hellenistic periods, the cult of Qos reached its peak, spearheaded by the migration of Edomite people to the southern hills of former Judah, a region now known by the Greek name of Idumaea.[7] Centuries later, Qos was worshiped by the Nabataeans of southern Transjordan and some northern Arabian groups. Qos disappears from our records in the first centuries C.E.

Edomite Theophoric names in the Bible

Some biblical names have the element of Qos in them, calling attention to the Edomite origins or religious affiliation of their bearers.[9]

Barkos (ברקוס)—literally “son of Qos” in Aramaic, appears once in the Bible, as the name of a head of a family of Judahite temple slaves that returned from the Babylonian captivity (Ezra 2:53; Neh 7:55). The same name appears on a Persian period Aramaic ostracon in Beersheba, and in an inscription from 6th/5th century B.C.E. Babylon (Akkadian ba-ar-ḳu-su).[10]

Kushaiah (קושיהו)— father of Ethan, a Merarite Levite who accompanies the ark of God on its return to Jerusalem (1 Chr 15:17).[11] The name may include both the theophoric element Qos[12] as well as YHWH, perhaps reflecting a syncretistic “Qaus is YHWH.”[13] Some scholars dismiss this understanding on the grounds that Qos is supposedly never spelled with š,[14] but the fact that the name qsmlk (“Qos is/has become king”) is written in at least one text as qšmlk, negates this objection.[15]

Obed Edom (עבד־אדום)—This name is given to four separate biblical characters:

- Obed Edom the “Gittite,” to whose house David brought the ark of God (2 Sam 6:10-12; 1 Chron 13:13-14);

- Obed Edom ben Jeduthun, a Levite that served as gatekeeper and musician before the ark of God in David’s times (1 Chron 15:18, 21, 24-25; 16:5, 38);

- Obed Edom, whose descendants are listed as temple gatekeepers in 1 Chron 26:4, 8, 15 (this may be the same person in the previous listing);

- Obed Edom, who lives during Amaziah’s reign, this time taking care of the temple treasures when Jehoash king of Israel pillaged the temple (2 Chron 25:24).

The name parallels the Yahwistic עובדיה Obadiah (Servant of Yah), and is an oblique reference to Qos. While the name means “servant of Edom,” it should likely be understood as “the servant of [Qos, the god/lord of] Edom.”[16]

Veiled Biblical References to Qos

Two biblical texts contain oblique references to Qos, playing on graphemic and phonetic similarities with the name of the Edomite god.

El-Qom/El-Qos in Proverbs

The first may be hidden behind a scribal error:

משלי ל:כט שְׁלֹשָׁ֣ה הֵ֭מָּה מֵיטִ֣יבֵי צָ֑עַד וְ֝אַרְבָּעָ֗ה מֵיטִ֥בֵי לָֽכֶת׃ ל:ל לַ֭יִשׁ גִּבֹּ֣ור בַּבְּהֵמָ֑ה וְלֹא־יָ֝שׁ֗וּב מִפְּנֵי־כֹֽל׃ ל:לא זַרְזִ֣יר מָתְנַ֣יִם אֹו־תָ֑יִשׁ וּ֝מֶ֗לֶךְ אַלְק֥וּם עִמֹּֽו׃

Prov 30:29 There are three that are stately of stride, four that carry themselves well:30:30 The lion is mightiest among the beasts, and recoils before none; 30:31 The greyhound, the he-goat, the king whom none dares resist. (NJPS)

The last phrase is very difficult, and some other translations are “and the king when he harangues his people” (NJB) and “and a king whose troops are with him” (NKJV).

Given the graphic similarity between the final mem and samekh, Theodor Vriezen suggested long ago reading ומלך אל קוס עמו “and the king with whom the god Qos is.”[17] The original meaning—perhaps the proverb itself originated in an Edomite context—was lost either because of Judean objections to referencing this deity positively or out of a later scribes’ ignorance of the meaning of Qos.

“Qos Shall Pass” in Lamentations

Another possible veiled reference appears to be an ironic usage:

איכה ד:כא שִׂ֤ישִׂי וְשִׂמְחִי֙ בַּת־אֱדֹ֔ום יֹושַׁבְתִּי בְּאֶ֣רֶץ ע֑וּץ גַּם־עָלַ֨יִךְ֙ תַּעֲבָר־כֹּ֔וס תִּשְׁכְּרִ֖י וְתִתְעָרִֽי׃ ס

Lam 4:21 Rejoice and exult, fair Edom, who dwell in the land of Uz! To you, too, the cup (kos) shall pass, you shall get drunk and expose your nakedness. (NJPS)

Gard Granerød of the Norwegian School of Theology, suggests that the biblical author is here playing with the written and oral similarities between the words כוס (cup) and the god קוס (Qos),[18] making a veiled reference to the Edomite god Qos, along the lines of “To you, too, may Qos pass by!”,[19] or even the more threatening, “Just as YHWH did this to us, soon Qos will turn to you and do this as well.”

Why Is the Bible Coy about Qos?

Considering the great popularity of Qos, especially in late Iron Age Judah and Persian Period Yehud, why do the biblical authors limit references to Qos to Edomite names or hidden word plays?

Several scholars have suggested that the cults of YHWH and Qos presented similar features or that, even, both deities originated from common roots.[20] Like Jacob and Esau, YHWH and Qos grew up together, so to speak. Both gods are first attested in Egyptian inscriptions dating to the late second millennium B.C.E., when the Egyptians encountered clans or tribes in the southern arid belt of the Levant (Negev, Edom) bearing those names.[21]

But even accepting the close affinity between Israel and Edom, and that both deities emerged from similar social and geographical backgrounds, it is clear that YHWH and Qos were, from the beginning, different deities. Thus, I believe the idea that Qos and YHWH are the same deity to be mistaken.

A Persian Period Cultural Clash

Instead, I suggest that the issue may have been the growing popularity of the Qos cult in Idumaea during the Persian and Hellenistic periods, in the former territory of Judah. The population of Idumaea was a multicultural society, with Edomites, Arabs, Judahites and others coexisting peacefully, if not mixing each other. The popularity of Qos clashed with the notions of robust monotheism and ethnic purity of the priestly circles of Yehud, especially since Qos was now being worshipped in what was once Judaean territory.[22]

The Persian Period book of Chronicles tells about how the Judaean king Amaziah brings “gods” from Edom (referred to here with the archaic term “sons of Seir”):

דברי הימים ב כה:יד וַיְהִ֗י אַחֲרֵ֨י בֹ֤וא אֲמַצְיָ֨הוּ֙ מֵֽהַכֹּ֣ות אֶת־אֲדֹומִ֔ים וַיָּבֵ֗א אֶת־אֱלֹהֵי֙ בְּנֵ֣י שֵׂעִ֔יר וַיַּֽעֲמִידֵ֥ם לֹ֖ו לֵאלֹהִ֑ים וְלִפְנֵיהֶ֥ם יִֽשְׁתַּחֲוֶ֖ה וְלָהֶ֥ם יְקַטֵּֽר:

2 Chron 25:14 After Amaziah returned from defeating the Edomites, he had the gods of the men of Seir brought, and installed them as his gods; he prostrated himself before them, and to them he made sacrifice. (NJPS)

Map of Edom and Idumaea from the Iron Age to the Roman period. (STNP = Southern Transjordan Negev Pottery.)

Notably, the earlier book of Kings, which was Chronicles primary source, does not have this story in the parallel text (2 Kings 14:7). This would suggest that the Persian Period author of 2 Chronicles 25:14 is here reflecting the situation of his own time, when worship of Edomite deities in Yehud was common.

As such, Qos became a direct competitor to YHWH. Paralleling the absence of Qos, the books of Ezra and Nehemiah are notorious for the lack of references to the Idumaean population, a historical amnesia that is more eloquent given the frequent allusions to the Arabs, their other (certainly not friendly) neighbors living south of Yehud.[23]

Idumaeans in the Temple

Judean animosity to any reference to Qos may also be connected to conflicts over the presence of Edomites holding temple cultic positions in Persian Period Jerusalem.

Edomites worshipping YHWH would be nothing new. In the (early) book of Samuel, Doeg the Edomite, one of Saul’s servants, encounters David when the latter is seeking refuge in the priestly city of Nob:

שמואל א כא:ח וְשָׁ֡ם אִישׁ֩ מֵעַבְדֵ֨י שָׁא֜וּל בַּיֹּ֣ום הַה֗וּא נֶעְצָר֙ לִפְנֵ֣י יְ־הוָ֔ה וּשְׁמֹ֖ו דֹּאֵ֣ג הָאֲדֹמִ֑י אַבִּ֥יר הָרֹעִ֖ים אֲשֶׁ֥ר לְשָׁאֽוּל׃

1 Sam 21:8 Now one of Saul’s officials was there that day, detained before YHWH; his name was Doeg the Edomite, Saul’s chief herdsman. (NJPS)[24]

Even though Doeg ends up executing the priests on Saul’s orders, the fact that he is at the priestly center at all implies he is a YHWH worshipper, though not a cultic official. In the book of Chronicles, however, Obed Edom and Kushaiah (see above) are described as holding cultic positions in king David’s times and later.

Again, that the Persian Period book of Chronicles places such people in Davidic times implies that the author is trying to explain the existence of such people in his own time by providing them with pedigreed eponymous ancestors.[25] As Chronicles would not easily admit the existence of Edomite cultic personnel in the Jerusalem Temple, he transforms these non-Israelite characters into pious Levites.[26]

The influx of people with Edomite pedigree in cultic positions was likely a source of discord for the authors of Ezra and Nehemiah, leading to a deliberate literary oblivion in which the only clue about the characters’ original background were their theophoric names.

Ignoring Idumaea and Qos: A Strategic Decision

In sum, political conflict between Judeans and Idumaeans in the Second Temple period, living together and competing for the same territory, brought about the biblical authors’ selective memory when it came to their unnamed and undiscussed neighbors and co-workers. These “hidden polemics,” by no means limited to the conflicts between Judeans and Idumaeans,[27] included ignoring the great Idumaean deity Qos, well known to the Judean scribes, and all but absent from their writings.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

December 20, 2022

|

Last Updated

March 25, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Juan Manuel Tebes is Professor at the Catholic University of Argentina, current Director of its Center of Studies of Ancient Near Eastern History, and Researcher at the National Research Council of Argentina (CONICET). He is Co-Editor of the Ancient Near East Monographs (Society of Biblical Literature) and former Editor-in-Chief of the scholarly journal Antiguo Oriente. Tebes has participated in archaeological expeditions in Jordan, Israel, and Turkey, and has also been research fellow at many institutions. He has recently published, with Christian Frevel, the collection of papers The Desert Origins of God: Yahweh’s Emergence and Early History in the Southern Levant and Northern Arabia (special volume of Entangled Religions 12/2; Bochum: Ruhr-Universität Bochum, 2021).

Essays on Related Topics: