Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Fire Pans in the Bible and Archaeology

High Priest Offering Incense on the Altar, illustration from Henry Davenport Northrop, “Treasures of the Bible,” published 1894. Wikimedia

Fire Pans in the Tabernacle and the Temple

The Hebrew word firepan (maḥtah, pl. maḥtot) derives from the root ח.ת.ה/י, which means “to take away/snatch up” or “to rake,”[1] usually as a reference to coals:

משלי ו:כז הֲיַחְתֶּה אִישׁ אֵשׁ בְּחֵיקוֹ וּבְגָדָיו לֹא תִשָּׂרַפְנָה.

Prov 6:27 Can a man rake embers into his bosom without burning his clothes?[2]

Thus literally, a maḥtāh is an object with which one moves or heaps coals or other burning embers, like a shovel or a pan.[3] We find several different maḥtot in the Bible:

Golden Maḥtot for lamps—Golden maḥtot are among the implements associated with the golden candelabra (menorah) of the Tabernacle:

שמות כה:לח וּמַלְקָחֶיהָ וּמַחְתֹּתֶיהָ זָהָב טָהוֹר.

Exod 25:38 and its tongs and fire pans of pure gold.[4]

The classical commentators (ad loc.) debate whether these were used to scrape away the ashes (Rashi), to hold the new oil and wick (ibn Ezra), or to gather and carry away the old oil and wick (R. Abraham ben HaRambam). Whatever they were used for, the lamps of the Jerusalem Temple also had them:

מלכים א ז:מט וְהַפֶּרַח וְהַנֵּרֹת וְהַמֶּלְקַחַיִם זָהָב. ז:נ וְהַסִּפּוֹת וְהַמְזַמְּרוֹת וְהַמִּזְרָקוֹת וְהַכַּפּוֹת וְהַמַּחְתּוֹת זָהָב סָגוּר

1 Kgs 7:49 and the petals, lamps, and tongs, of gold; 7:50 the basins, snuffers, sprinkling bowls, ladles, and fire pans, of solid gold. [5]

Copper (or bronze) maḥtot for the main altar—Other maḥtot were accoutrements of the Tabernacle’s main altar, a large wooden edifice overlaid with copper, upon which animal sacrifices were burnt:

שמות כז:ג וְעָשִׂיתָ סִּירֹתָיו לְדַשְּׁנוֹ וְיָעָיו וּמִזְרְקֹתָיו וּמִזְלְגֹתָיו וּמַחְתֹּתָיו לְכָל כֵּלָיו תַּעֲשֶׂה נְחֹשֶׁת.

Exod 27:3 Make the pails for removing its ashes, as well as its scrapers, basins, flesh hooks, and fire pans — make all its utensils of copper.[6]

Their exact use is not specified, though here most commentators agree that their purpose was to scrape away the old coals and carry them away.[7] Rashi further claims (ad loc.) that they were also used to carry coals from the outer altar into the Tabernacle to place on the golden incense altar (or to be used in the Yom Kippur incense ritual, see below), as per the conception found in rabbinic sources (e.g., m. Yoma 4:3–4, t. Yoma 2:11).

Gold and silver maḥtot for the incense altar (Mishnah)—Notably, the Torah never says that the golden incense altar had maḥtot (Exod 30:1–10, 37:25–29). Nevertheless, the Mishnah (2nd cent, C.E.) takes this for granted (m. Tamid 5:5, 6:2):

מי שזכה במחתה נטל מחתת הכסף ועלה לראש המזבח ופנה את הגחלים הילך והילך וחתה ירד ועירן לתוך של זהב…

Whichever [priest] was chosen for the fire pan, took the silver fire pan and went to the top of the altar. He would clear away the coals this way and that, and scoop them up. Then he would descend and pour them into the golden [firepan]….

מי שזכה במחתה צבר את הגחלים על גבי המזבח ורדדן בשולי המחתה…

Whichever [priest] was chosen for the fire pan made a heap of the cinders on the top of the altar and then spread them about with the end of the fire pan….

Here the fire pans are not copper but silver and gold, to match the precious metals that coated the incense altar. [8] Other than that, they appear to function just like the maḥtot of the outer altar.[9]

Maḥtot for offering incense—A third use of maḥtot is for carrying and offering burning incense. For example, Leviticus 16:12 describes a Tabernacle ritual performed by the high priest on the Yom Kippur (the Day of Atonement):

ויקרא טז:יב וְלָקַח מְלֹא הַמַּחְתָּה גַּחֲלֵי אֵשׁ מֵעַל הַמִּזְבֵּחַ מִלִּפְנֵי יְ־הוָה וּמְלֹא חָפְנָיו קְטֹרֶת סַמִּים דַּקָּה וְהֵבִיא מִבֵּית לַפָּרֹכֶת. טז:יג וְנָתַן אֶת הַקְּטֹרֶת עַל הָאֵשׁ לִפְנֵי יְ־הוָה וְכִסָּה עֲנַן הַקְּטֹרֶת אֶת הַכַּפֹּרֶת אֲשֶׁר עַל הָעֵדוּת וְלֹא יָמוּת.

Lev 16:12 And he shall take a panful of glowing coals scooped from the altar before YHWH, and two handfuls of finely ground aromatic incense, and bring this behind the curtain. 16:13 He shall put the incense on the fire before YHWH, so that the cloud from the incense screens the cover that is over the Testimony, lest he die.

Although the Torah does not specify which altar the coals should be taken from, the Talmud (b. Yoma 45b) claims it is not the incense altar but the outside altar. Either way, the fire pan here functions as a utensil that can carry burning embers from one place to another, in this case to bring coals burning incense into the inner sanctum.[10]

Thus, fire pans can be as implements for altars, to place or remove coals, or as objects for offering incense in their own rights. This latter usage plays a prominent role in two Priestly stories in the Torah.

Nadav and Avihu’s Firepan Offering

In the story describing the death of Aaron’s two sons, Nadav and Avihu, upon bringing the “strange fire” as an offering,[11] we are told:

ויקרא י:א וַיִּקְחוּ בְנֵי אַהֲרֹן נָדָב וַאֲבִיהוּא אִישׁ מַחְתָּתוֹ וַיִּתְּנוּ בָהֵן אֵשׁ וַיָּשִׂימוּ עָלֶיהָ קְטֹרֶת וַיַּקְרִבוּ לִפְנֵי יְ־הוָה אֵשׁ זָרָה אֲשֶׁר לֹא צִוָּה אֹתָם.

Lev 10:1 Now Aaron’s sons Nadav and Avihu each took his fire pan, put fire in it, and laid incense on it; and they offered before YHWH alien fire, which He had not enjoined upon them.[12]

Nadav and Avihu use portable fire pans to carry burning embers and incense, to bring an offering (ק.ר.ב) to God. Although God rejects this particular “strange fire,” such a method of offering incense was clearly considered legitimate, as we can see from the collection of firepan incidents in Numbers 16–17.

The Fire Pans of Aaron and the 250 Chieftains

In the Korah story, fire pans appear prominently three separate times. The story begins when 250 chieftains of the nation, led by the Levite Korah, challenge the authority of Moses and Aaron, claiming instead that cultic leadership should be available to all Israelites (Num 16:2–3).[13] Moses responds by devising a test according to which each person would offer incense to YHWH on a portable firepan:

במדבר טז:ו זֹאת עֲשׂוּ קְחוּ לָכֶם מַחְתּוֹת… טז:ז וּתְנוּ בָהֵן אֵשׁ וְשִׂימוּ עֲלֵיהֶן קְטֹרֶת לִפְנֵי יְ־הוָה מָחָר וְהָיָה הָאִישׁ אֲשֶׁר יִבְחַר יְ־הוָה הוּא הַקָּדוֹשׁ…

Num 16:6 Do this: Take fire pans… 16:7 and tomorrow put fire in them and lay incense on them before YHWH. Then the man whom YHWH chooses, he shall be the holy one….

The next day, Moses reiterates what those taking part in the test should do:

במדבר טז:יז וּקְחוּ אִישׁ מַחְתָּתוֹ וּנְתַתֶּם עֲלֵיהֶם קְטֹרֶת וְהִקְרַבְתֶּם לִפְנֵי יְ־הוָה אִישׁ מַחְתָּתוֹ חֲמִשִּׁים וּמָאתַיִם מַחְתֹּת וְאַתָּה וְאַהֲרֹן אִישׁ מַחְתָּתוֹ.

Num 16:17 Each of you take his fire pan and lay incense on it, and each of you bring his fire pan before YHWH, two hundred and fifty fire pans; you and Aaron also [bring] your fire pans.”

The trial then takes place to disastrous effect for the 250 challengers (the sign // marks where the intervening non-Priestly text is being skipped):

במדבר טז:יח וַיִּקְחוּ אִישׁ מַחְתָּתוֹ וַיִּתְּנוּ עֲלֵיהֶם אֵשׁ וַיָּשִׂימוּ עֲלֵיהֶם קְטֹרֶת וַיַּעַמְדוּ פֶּתַח אֹהֶל מוֹעֵד וּמֹשֶׁה וְאַהֲרֹן. // טז:לה וְאֵשׁ יָצְאָה מֵאֵת יְ־הוָה וַתֹּאכַל אֵת הַחֲמִשִּׁים וּמָאתַיִם אִישׁ מַקְרִיבֵי הַקְּטֹרֶת.

Num 16:18 Each of them took his fire pan, put fire in it, laid incense on it, and took his place at the entrance of the Tent of Meeting, as did Moses and Aaron. // 16:35 And a fire went forth from YHWH and consumed the two hundred and fifty men offering the incense.

According to the story, the incense was offered in portable fire pans carried by each of the participants and brought forward as an offering (ק.ר.ב), likely involving a lifting up motion of offering. (Incense rituals included lifting the smoking fire pans up, thus bringing them near before God and making the ritual perceptible.[14] )

Turning the Fire Pans into Plating

The Torah continues with God instructing Moses to tell Elazar the priest to use these fire pans as plating for the altar:

במדבר יז:ד וַיִּקַּח אֶלְעָזָר הַכֹּהֵן אֵת מַחְתּוֹת הַנְּחֹשֶׁת אֲשֶׁר הִקְרִיבוּ הַשְּׂרֻפִים וַיְרַקְּעוּם צִפּוּי לַמִּזְבֵּחַ.

Num 17:4 Elazar the priest took the copper (or “bronze”) fire pans which had been used for offering by those who died in the fire; and they were hammered into plating for the altar.

Here we learn that the pans are made of copper or bronze, like the maḥtot of the large altar.[15]

Aaron’s Fire Pan

In the following story, the people complain about Moses and Aaron causing the death of “God’s people.” As a result, a plague breaks out as a punishment, and in response, Moses instructs Aaron:

במדבר יז:יא קַח אֶת הַמַּחְתָּה וְתֶן עָלֶיהָ אֵשׁ מֵעַל הַמִּזְבֵּחַ וְשִׂים קְטֹרֶת וְהוֹלֵךְ מְהֵרָה אֶל הָעֵדָה וְכַפֵּר עֲלֵיהֶם.

Num 17:11 Take the fire pan and put on it fire from the altar. Add incense and take it quickly to the community and make expiation for them.[16]

This too shows that offering incense to YHWH on a portable fire pan is legitimate, at least as long as Aaron is offering it with the consent of God or Moses—since Aaron’s offering successfully stops the plague.

Early History of Fire Pans

What are maḥtot exactly? Thanks to archaeology, we have a very good idea of what these ritual fire pans looked like and how they functioned.

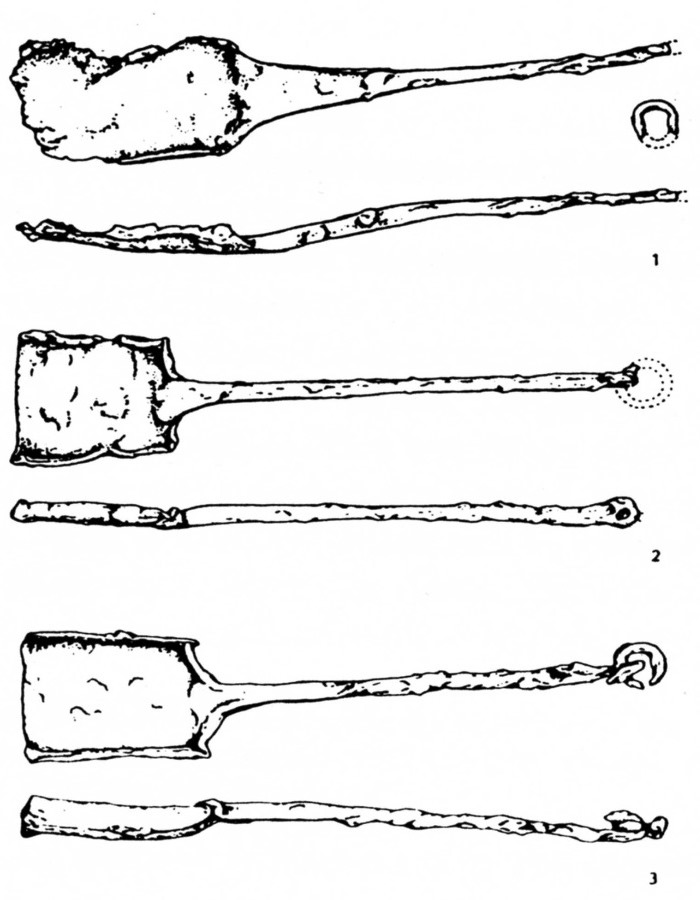

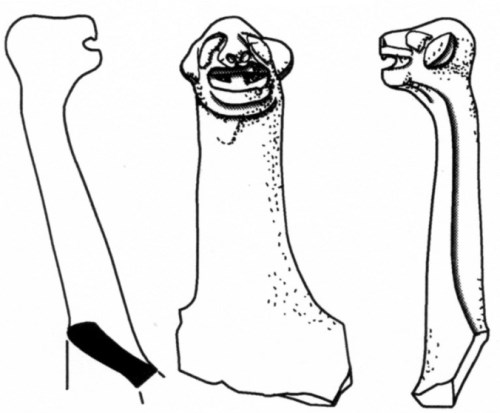

Fig.1: Clay fire pan from Tel Ahmar in Syria, after Mazzoni, S. 2000. Handled pans from Ebla… in: Dittmann, R. et al. (eds.), Variatio Delectat (AOAT 272). Münster: Fig. 22

Fig.1: Clay fire pan from Tel Ahmar in Syria, after Mazzoni, S. 2000. Handled pans from Ebla… in: Dittmann, R. et al. (eds.), Variatio Delectat (AOAT 272). Münster: Fig. 22

Fire pans were made of clay, metal, and stone.[17] They first appear in the late third and early second Millennia B.C.E. (Fig. 1). Rectangular, metal fire pans with long handles are known from Late Bronze Age Cyprus and Sardinia in contexts that suggest shoveling coals. They also appear in Israel at Megiddo and Beth Shemesh. In the Iron Age such fire pans are found in Cyprus and near the altar at Tel Dan (Fig. 2).[18]

Not every vessel with traces of burning was used for incense. Various vessels were used for cooking of food, to provide light, as portable heaters, etc. That said, the use of incense was widespread in the ancient world and would have been one of the main purposes for fire pans, and not only for those who could afford exotic imports. Local plants could be used and not just expensive myrrh and frankincense.

|

|

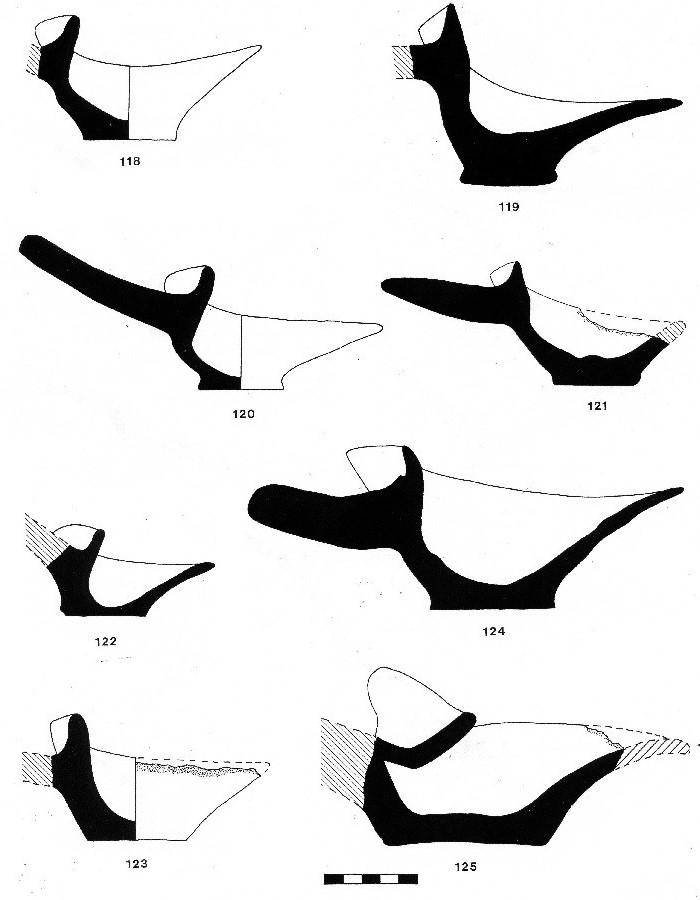

| Fig. 2: Fire pans from the Temple of Dan, After Biran 1992:165. Courtesy of David Ilan, Nelson Glueck School (HUC) | Fig. 3: Aegean fire pans from Aya Irini, Second Millennium BCE, after Georgiou 1983: Pl. 6. Von Zabern Verlag |

In the second millennium B.C.E., the Aegean world manufactured hundreds of a certain type of fire pan called a “scuttle,” i.e., “a shallow wheel made cup with a handle that is attached to the lip and indents it.”[19] They are found in Crete, the Greek islands, mainland Greece, Western Anatolia and Cyprus (Fig. 3). Four scuttles found in Crete were noted as having coals inside. Some were found in temples at Kephala and Kommos implying a ritual function.[20]

Many fire pans were found in 6th–4th centuries B.C.E. Cyprus. (Fig. 4).[21] During this period the shape varies, from rounded to flat bases. Again, many were found in sacred precincts, especially near altars. Some are charred. They were probably used to burn incense in rituals and later broken and deposited in pits (bothroi). The handles sometimes have finials of animal heads – especially rams.

|

|

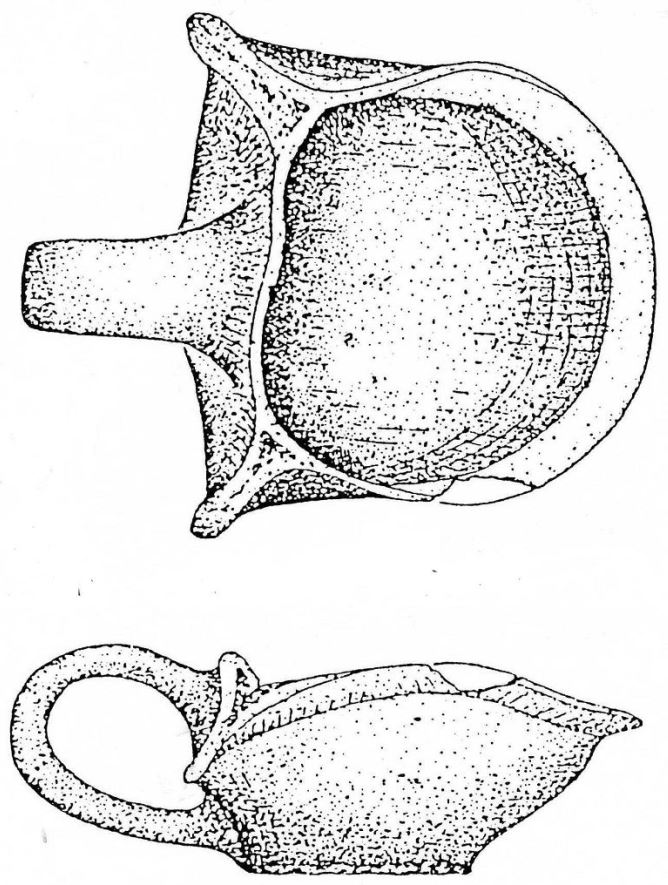

| Fig. 4: Cypriot fire pans, after Buchholtz 1994: Figs. 2c, 8f. | Fig. 5: Fire pan bowl with a handle, after Bennett, E.L. and Blegen, C.W. 1955. The Pylos Tablets TA712. Princeton: 82. |

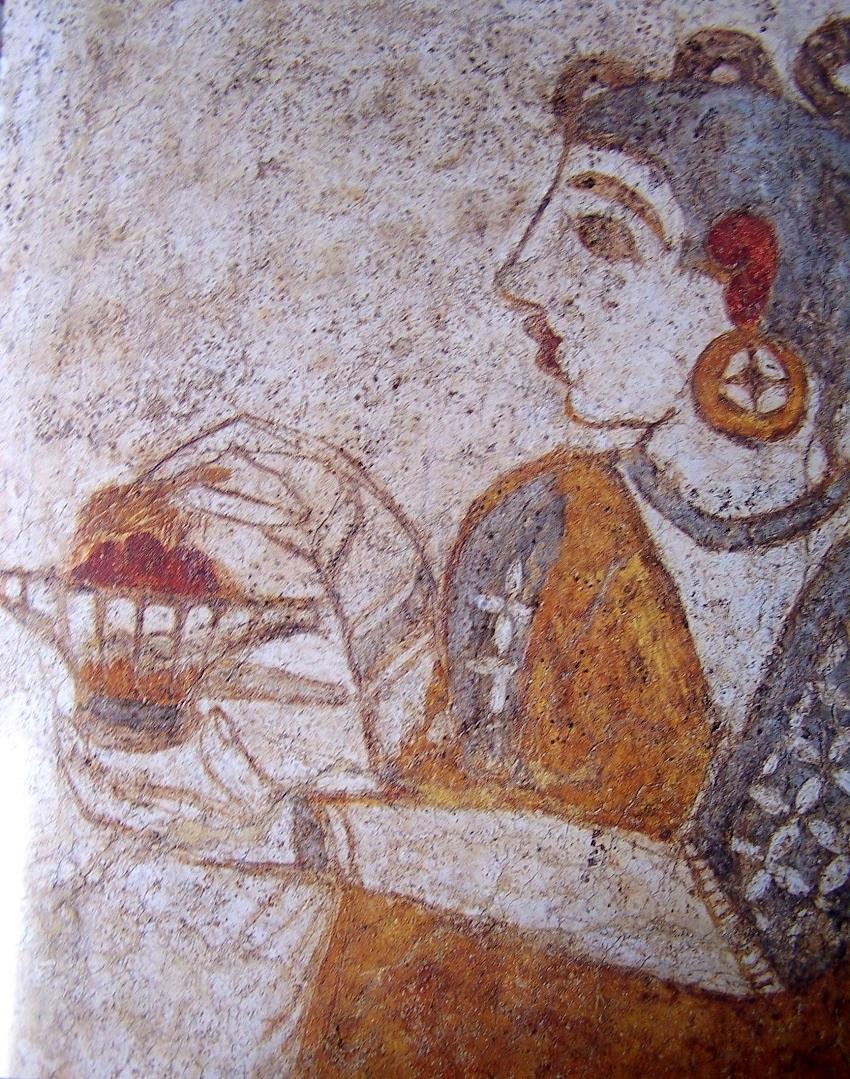

Fire pans are documented in texts from Pylos (Fig. 5). A fresco from Thera/Akrotiri shows a woman (priestess?) holding a fire pan, which seems to have glowing coals inside (Fig. 6). She is sprinkling some substance upon the coals, perhaps crocus stamens.[22]

Fig. 6: Thera/Akrotiri scene of a priestess (?) sprinkling incense on a fire pan with glowing coals, after Doumas 1992: Pl. 24 Idryma-theras.org

Fig. 6: Thera/Akrotiri scene of a priestess (?) sprinkling incense on a fire pan with glowing coals, after Doumas 1992: Pl. 24 Idryma-theras.org

The Fire Pans of Yavneh

This survey above gives us a sense of fire pans in the Aegean world, but what about the Levant?

During my excavation of Yavneh, in a Philistine Iron Age II favissa (repository pit or genizah [23]), my team and I found mysterious vessels together with a host of cultic objects (clay and stone altars, cult stands, burnt and broken bowls and chalices): lamp-shaped bowls with an attached handle (Fig 7). The bowls could be solid or, less commonly, perforated (Fig 8).

|

|

| Fig. 7: Fire pan from Yavneh. Note the marks of burning inside. Photo R. Kletter. | Fig. 8: Perforated fire pan from Yavneh. Photo R. Kletter. |

We estimate that there were about 60 such vessels in the pit (Fig 9 – shown vertical, it was roughly diagonal when attached to the bowl). The handles of these objects vary: some are vertical loop handles, others are horizontal and either hollow or solid. Three handles show schematic animal faces (Fig. 10).

|

|

| Fig. 9: Drawing by Yulia Rodman. | Fig. 10: A box with fragments of fire pans as found in the pit. The grey surface color comes from the layer of ash, in which the fragments have been found. Photo R. Kletter |

Such vessels were practically unknown in in the southern Levant before. Only a few comparisons are documented in Philistine sites and in the Edomite favissa at En Ḥaṣevah.[24]

Some of the vessels show traces of burning, usually inside the bowl and outside at the base. The sections of the fragments indicate thermal shock, not just superficial surface discoloration. The pattern of burning suggests that the vessel held hot coals, and that they were used as a shovel to scrape coals in a sliding movement, that is, to move fire from place to place.

They could also be used as incense burners. (Although in our analysis of the two fire pan samples, no traces of incense were found, this does not mean they weren’t used for incense, since the incense would have been placed on top of the coals, not in direct contact with the clay vessels.)

It is not surprising that the Yavneh vessels show affinities to the common Levantine and Cypriot Iron Age lamps with rounded/flattened bases, as both were used for holding burning fuel or embers.[25] The holes at the base were pierced from inside (another indication that the inside of the bowl was the “working” part), probably to enhance air supply for the coals.

Maḥtot in Art and Interpretation

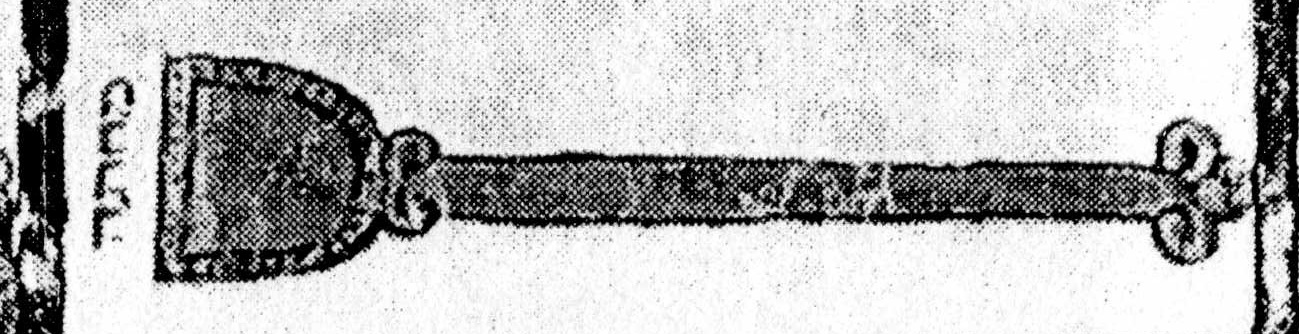

In late antiquity (3rd–6th cent. C.E.), rectangular maḥtot are common in Synagogue art.[26] (Fig. 11) At Sepphoris the maḥtāh is gray (hinting that it is a metallic vessel), with dark red spots, apparently meant to represent burning coals. Although this was not the only kind of fire pans used during this period, as both round and rectangular clay fire pans—with remnants of lids—were found in Sepphoris,[27] rectangular metal fire pans like the ones in the pictures were found in various excavations from this period (Bethsaida, the Cave of Letters [with traces of burning], and Sepphoris).[28] (Fig. 12)

.jpeg?alt=media&token=c5303482-3985-4448-af9c-8f39d9a21c8f) |

|

| Fig. 11: Rectangular fire pan from Hamat Tiberias, after Freund 1999: Fig. 5. Courtesy of Rami Arav | Fig. 12: Metal fire pan from Bethsaidah, after Freund 1999: 34, Fig. 22a. Courtesy of Rami Arav |

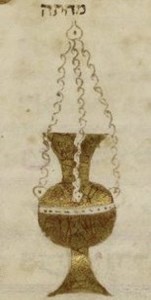

Something changes however in the art during the 10th–15th centuries C.E. When we look at frontispieces of Jewish manuscripts showing the maḥtôt of the Tabernacle/ Temple (Fig. 13), we begin to see two styles of fire pan imagery: The most common depiction is of open pans, resembling the synagogue art discussed above, but sometimes the fire pans are depicted as closed vessels carried by chains.

Fig. 13: Detail from Hebrew manuscript with a fire pan on the left, after Reval-Neher 2005: Fig. 32

Fig. 13: Detail from Hebrew manuscript with a fire pan on the left, after Reval-Neher 2005: Fig. 32

This new way of depicting the Tabernacle / Temple fire pans has its origins in the fact that, in the Byzantine Period, fire pans went from being open vessels with handles to closed, cup-like censers, with chains, [29] the later type still in use today (Fig. 14).[30] Later artists, who no longer knew the ancient fire pans, depicted the biblical heroes with closed incense censers of the type found since the Byzantine period (Fig 15).

Biblical Fire Pans and the Yavneh Repository Pit

Many scholars date the Priestly stories in the Torah to the Persian period, making them substantially later than the Yavneh repository pit; but fire pans kept their characteristics for a long time.

The biblical sources do not specify exact shapes for the maḥtot; both round and rectangular fire pans existed since early times, and the Bible may not distinguish based on shape. Though the Yavneh fire pans find close parallels in the Aegean World and Cyprus, their shape is also related to Levantine and Cypriot lamps, which were open at the top. When we look at the Yavneh fire pans, we can beautifully picture what is happening in the stories about Korah and Nadab and Abihu.

Nadav and Avihu and the 250 chieftains lift up their burning maḥtot towards God. They held open fire pans, of the type found at Yavneh—not closed vessels of the Byzantine and later type—and God replies by pouring fire from above on them. It is a symmetric picture, with two opposing movements.

This picture became obscured when some later interpreters viewed the biblical fire pans through the prism of what they were familiar with. Luckily, archaeology allows us to turn back the clock and understand what the biblical authors were envisioning.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

July 3, 2019

|

Last Updated

April 8, 2024

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Footnotes

Dr. Raz Kletter is Docent for Near Eastern Archaeology and Member of CSTT/ANEE in Helsinki University. Before that he was senior excavating archaeologist, and head of the SPR Unit in the Israel Antiquities Authority, and a lecturer at Haifa University. He holds a Ph.D. in archaeology from Tel Aviv University and has led a number of archaeological excavations, including that of Yavneh. Among his publications The Judean Pillar Figurines and the Archaeology of Asherah (1996), Economic Keystones. The Weight System of the Kingdom of Judah (1998), Yavneh I-II. The Excavation of the “Temple Hill” Repository Pit and the Cult Stands (with Irit Ziffer and Wolfgang Zwickel, 2010, 2015), and most recently, Archaeology, Heritage and Ethics in the Western Wall Plaza, Jerusalem (2019).

Essays on Related Topics: