Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Looking Through the Window: A Gendered Motif

Naomi Cassuto, Sippur bemisparayim (Paper cuts) Jerusalem, 2017

The window is a recurrent motif in art from antiquity to the present. On one hand, the window allows and sometimes invites the outsider or viewer to intrude into the private space of someone else and satisfy their curiosity or even prurient interest. On the other hand, it allows someone cloistered inside to look out to see the real world, to become enlightened. Both of these are at play in the story of Isaac and Rebekah’s move to Gerar.

Abimelech Sees Isaac and Rebekah Through the Window

Isaac and Rebekah move to the city of Gerar because of a famine, and, as his father did before him (Gen 20:1-18), Isaac tells Abimelech that Rebekah is his sister and not his wife. Unlike in the case of Abraham and Sarah, however, Abimelech does not immediately take Rebekah, and the couple live together peacefully, and even become complacent, until:

בראשית כו:ח וַיְהִי כִּי אָרְכוּ לוֹ שָׁם הַיָּמִים וַיַּשְׁקֵף אֲבִימֶלֶךְ מֶלֶךְ פְּלִשְׁתִּים בְּעַד הַחַלּוֹן וַיַּרְא וְהִנֵּה יִצְחָק מְצַחֵק אֵת רִבְקָה אִשְׁתּו.

Gen 26:8 When some time had passed, Abimelech king of the Philistines looked through the window, and he saw Isaac being playful (the Hebrew is a word play on his name) with his wife Rebecca.

Whose window was Abimelech looking through? The story is ambiguous on this point.

Isaac and Rebekah’s Window

Rashi (1040-1105) believes that Abimelech was actually peeping into their window at their private quarters and that the couple were being intimate:

וישקף אבימלך – ראהו משמש מטתו.

Abimelech looked – he saw him having sex.[1]

Shadal (1800-1865) also reads the verse to mean Isaac and Rebekah’s window, but assumes that Abimelech was not peeping, but rather that the window was easily accessible to anyone on the street and Abimelech just happened to see them:

מצחק את רבקה אשתו – מעשי געגועים שאין אדם כשר עושה עם אחותו (אך אין להאמין שהיה יצחק משמש מטתו במקום שהיה אפשר ליושבי בית אחר או לעוברי דרך לראותו בעד החלון).

Being playful with his wife, Rebekah – frolicsome behavior that a decent person does not do with his sister (but it is impossible to believe Isaac was having sex in an easily visible place such that someone sitting in his own house or passing by on the street could see through the window).[2]

Abimelech’s Window

The verse could also be read to imply that Abimelech saw them through his own window. For example, in his JPS commentary (ad loc.), Nahum Sarna (1923-2005) writes:

The definite article suggests a specific window, most likely the one in the outer court of the royal palace, at which the king showed himself to the people on ceremonial occasions.

Yehuda Kiel (1916-2011), in his Daat Miqra commentary (ad loc.), comes to the same conclusion:

בעד החלון סובל שתי פירושים: האחד בעד חלון ביתו=ארמונו, והאחר בעד חלוק ביתו של יצחק…. והכינוי מלך פלשתים בא להטעם שההשקפה היתה מארמון ביתו.

“Through the window” can be interpreted in two ways: One way is “through the window of his house=palace,” the other is “through the window of Isaac’s house.” … The use of the modifying phrase “king of the Philistines” comes to clarify that the looking was done from [Abimelech’s] own house/palace.

This possibility is strengthened when we remember that palaces are large, with large windows, often high up. Thus, Abimelech would have had a grand view of many houses.[3] In his Midrash Sekhel Tov (ad loc.), R. Menachem ben Shelomo (12th century) supports this idea by noting that the verb used regarding Abimelech’s looking, וישקף, often has the connotation of looking down:

אין השקפה אלא מלמעלה למטה

The term hashkafa always implies from above to below.[4]

This same point is made in modern lexica such as BDB, which translates the verb as “look out and down” and HALOT which translates “look down from above.”

Both Windows

Some commentators have expressed ambivalence regarding which window the verse refers to, and read the phrase as referring to both windows. For example, in his commentary on Genesis (ad loc.), Hermann Gunkel writes:

The—very idyllic—scene is probably to be envisioned as follows. Isaac and Abimelech live across from each other on a narrow alley where one can see from the window of one house into the other.

The combo interpretation is beautifully illustrated in Naomi Cassuto’s paper cut (see above) where we see Abimelech looking through the window at the couple modestly embracing within their own tent.

Legal Implications

Rabbinic literature (m. Baba Batra 3:7) discusses the legal implications of making or enlarging a window over a neighbor’s courtyard, and it deals with the very concern dealt with in Gunkel and Naomi Cassuto’s interpretation:

לא יפתח אדם לחצר השותפין פתח כנגד פתח וחלון כנגד חלון

In a joint courtyard, a person may not make a door facing another person’s door or a window facing another window.

The concern here is that such an opening would infringe on a neighbor’s right to privacy, a concept known in Rabbinic literature as “damage through seeing” [5](היזק ראייה). The Rabbis were concerned with the distinction of the public (רשות הרבים) and private (רשות היחיד) domains and how they impinge upon each other.[6]

Male Motif – Window Allows One to Learn the Truth

Which window Abimelech used to see in to Isaac and Rebekah may be a logistical question, but the story actually makes use of an additional motif prominent in biblical texts, namely, using a window to see out.

For example, Proverbs 7:6-23 describes a prostitute’s seduction of a foolish young man. The whole exchange is being watched by the narrator of Proverbs who describes what he sees:

משלי ז:ו כִּי בְּחַלּוֹן בֵּיתִי בְּעַד אֶשְׁנַבִּי נִשְׁקָפְתִּי.

Prov 7:6 From the window of my house through my lattice I looked out,

ז:ז וָאֵרֶא בַפְּתָאיִם אָבִינָה בַבָּנִים נַעַר חֲסַר לֵב.

7:7 and I saw among the simple, noticed among the youths, a lad devoid of sense.

ז:ח עֹבֵר בַּשּׁוּק אֵצֶל פִּנָּהּ וְדֶרֶךְ בֵּיתָהּ יִצְעָד.

7:8 He was crossing the street near her corner, walking toward her house.

Here, the narrator, looking out his window, sees the truth of what is happening whereas the naïve young man passing by the house of the married woman—perhaps a prostitute—has no idea. The narrator uses this knowledge to inform the reader of the dangers of the “seductive woman” he witnessed through his window.

Similarly, Abimelech’s use of the window reflects a positive motif. His look through the window is enlightening, since once he sees Isaac and Rebekah being playful he realizes that he has been tricked and understands the complete picture, preventing him from committing adultery. Thus, for Abimelech, the window is empowering, granting him access to new and correct knowledge of the world outside his palace.

The Female Version

In both the Abimelech story and the Proverbs passage, the person who learns the truth by looking through his window is a man. The motif, however, works the opposite way when it is used for women, where it highlights an inside-outside dichotomy, namely, the woman’s passivity and her inability to get the full picture of what is occurring in the bright space of the outside world just by peering through the window from the shadow of her home.

The female version of the window motif found literary expression in the biblical portrayals of three aristocratic women looking out at a man’s world, but not fully aware of the implications of what it holds in store for them.

Sisera’s Mother

The book of Judges tells the story of Israel’s war with Jabin, king of the Canaanite city Hazor, and his powerful general Sisera. The prophetess Deborah and her chosen military commander, Barak ben Avinoam, lead the battle, and Sisera’s army is defeated. Judges 5 records a song sung by Deborah about this battle, including a final description of the scene in which the mother of Sisera (Judges 5:28-31) is waiting for her heroic son to come home. As she waits, she is sitting in her house, and looking anxiously out the window:

שופטים ה:כח בְּעַד הַחַלּוֹן נִשְׁקְפָה וַתְּיַבֵּב אֵם סִיסְרָא בְּעַד הָאֶשְׁנָב מַדּוּעַ בֹּשֵׁשׁ רִכְבּוֹ לָבוֹא מַדּוּעַ אֶחֱרוּ פַּעֲמֵי מַרְכְּבוֹתָיו.

Judg 5:28 Through the window she peered Sisera’s mother whined behind the lattice: “Why is his chariot so long in coming? Why so late the clatter of his wheels?”

Unsure why the army has not yet returned, and unwilling or unable to face the possibility that it is because they were defeated, she tells herself that his tarrying is a result of being busy dividing the spoils of victory. In fact, Sisera has been killed by Yael, which will probably leave his mother forsaken in her old age.

Michal the Daughter of Saul and the Wife of David

This motif is also found with Michal, the daughter of King Saul and wife of King David, living in the royal palace in Jerusalem. In the story, David is bringing the Ark of the Covenant from the house of Oved Edom the Gittite to Jerusalem. The previous attempt to bring the ark to Jerusalem failed, as God got angry at one of the participants and struck him down, and thus David himself is managing the proceedings and showing as much joy as possible. Michal, however, sees the matter differently.

שמואל ב ו:טז טז וְהָיָה אֲרוֹן יְהֹוָ-ה בָּא עִיר דָּוִד וּמִיכַל בַּת שָׁאוּל נִשְׁקְפָה בְּעַד הַחַלּוֹן וַתֵּרֶא אֶת-הַמֶּלֶךְ דָּוִד מְפַזֵּז וּמְכַרְכֵּר לִפְנֵי ה’ וַתִּבֶז לוֹ בְּלִבָּהּ.

2 Sam 6:16 “As the Ark of the Lord entered the City of David, Michal, daughter of Saul, looked out of the window and saw King David leaping and whirling before the Lord; and she despised him for it.”

As she looks out of the window, Michal, the daughter of the previous king, sees her husband, the current king, dancing in the street half naked like a commoner and chastises him for it. She does not understand her husband’s religious fervor, and David responds harshly. The story ends on a sad note, by reporting that Michal died childless (2 Sam 6:23), perhaps implying the practical termination of their union.

Jezebel the Queen Mother

The third lady partaking in this motif is Jezebel the Phoenician wife of King Ahab and the queen mother of King Joram. When Joram’s general, Jehu, leads a coup against him, he heads to the king’s palace in Jezreel and assassinates him on the road, after which he enters the city, where the queen mother is also staying. The story notes:

מלכים ב ט:ל וְאִיזֶבֶל שָׁמְעָה וַתָּשֶׂם בַּפּוּךְ עֵינֶיהָ וַתֵּיטֶב אֶת-רֹאשָׁהּ וַתַּשְׁקֵף בְּעַד הַחַלּוֹן.

2 Kings 9:30 When Jezebel heard of it, she painted her eyes with kohl and dressed her hair, and she looked out of the window.

Jezebel sees what is happening, and after beautifying herself, calls him a traitor. But Jehu is more than a mere traitor; he is the new anointed king. As one of his first acts, Jehu then has Jezebel thrown out that same window, her body left for the dogs.

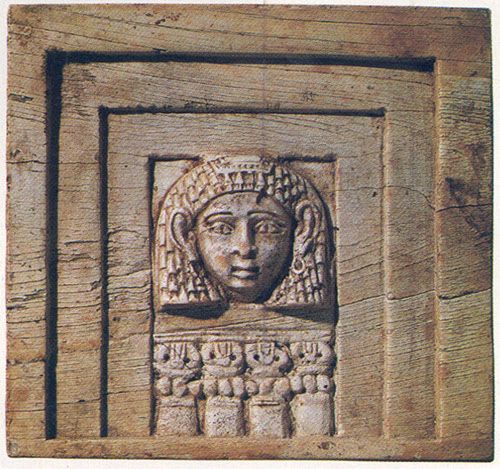

An Ivory “Woman in the Window”

The prophet Amos refers to the use of ivory to decorate palaces in 9th century Israel:

עמוס ג:טו וְהִכֵּיתִי בֵית הַחֹרֶף עַל בֵּית הַקָּיִץ וְאָבְדוּ בָּתֵּי הַשֵּׁן וְסָפוּ בָּתִּים רַבִּים נְאֻם ה’.

Amos 3:15 I will wreck the winter palace together with the summer palace; the ivory decorated homes[7] shall be demolished and the great houses shall be destroyed — declares the Lord.

עמוס ו:ד הַשֹּׁכְבִים עַל מִטּוֹת שֵׁן וּסְרֻחִים עַל עַרְשׂוֹתָם וְאֹכְלִים כָּרִים מִצֹּאן וַעֲגָלִים מִתּוֹךְ מַרְבֵּק.

Amos 6:4 They lie on ivory beds, lolling on their couches, feasting on lambs from the flock and on calves from the stalls.

Amos is specifically pillorying the wealthy people’s use of luxury items while the poor remain downtrodden. One such ivory product has been uncovered in archaeological excavations in Samaria are decorative plaques with ivory inlay. These items were popular throughout the Levant during this period. The ones found in Samaria likely reflect local production.[8]

Several of these plaques illustrate the iconographic motif of the “Woman in the Window.”[9]She is depicted as an aristocratic lady, neither a goddess nor a cultic prostitute, bedecked with wig and jewelry, an image that is found around the eastern Mediterranean area.

Symbolically, the Woman in the Window was protected from the outside world by the double or triple inset of the window frames—reminiscent of picture frames—above a four-columned balustrade, associated with palatial architecture.

The Window as an Expression of Distance

The biblical stories use the window motif to underline the aloofness of these aristocratic women. Unlike men such as Abimelech and the narrator of Proverbs 7, who gain the full picture of reality by peering through their windows, the women who peer at the outside world through the window are unable to comprehend fully the reality that would soon affect them directly.

Afterword

Using the Window: Gender Neutral?

Although the “looking through the window” motif has a stark male-female dichotomy, when used more broadly, even female characters make active use of windows to positive effect.

Saving Joshua’s Spies (Rahab)

Before crossing the Jordan River to attack the city of Jericho, Joshua sends two spies. The locals become aware of the spies, and they hide in the house of the prostitute Rahab, who turns out to be sympathetic to the Israelite cause and agrees to save them in exchange for a promise that she and her family would not be harmed in the subsequent assault. Luckily, Rahab lives in a house attached to the city wall, and she has a window to the outside:

יהושע ב:טו וַתּוֹרִדֵם בַּחֶבֶל בְּעַד הַחַלּוֹן כִּי בֵיתָהּ בְּקִיר הַחוֹמָה וּבַחוֹמָה הִיא יוֹשָׁבֶת.

Josh 2:15 She let them down by a rope through the window — for her dwelling was within the city wall where she lived.

Rahab uses her window to the outside as a way of communicating with the Israelites outside the wall and saving herself and her family.

This case shows the very different use the biblical story makes of the window. Rahab is a woman, and, as we’ve seen, windows in biblical stories are used to paint the woman in a negative light, to emphasize the distance between what she sees and the reality of the man’s world. Here, however, Rahab is not looking out a window, but actively lowering men out the window and communicating with them. Thus, her use of the window does not mark her as aloof or passive; instead, she dominates the story entirely, and succeeds in fooling the king of Jericho and negotiating with the leader of the Israelite—all from her window.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

November 15, 2017

|

Last Updated

February 5, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Aaron Demsky is Professor (emeritus) of Biblical History at The Israel and Golda Koschitsky Department of Jewish History and Contemporary Jewry, Bar Ilan University. He is also the founder and director of The Project for the Study of Jewish Names. Demsky received the Bialik Prize (2014) for his book, Literacy in Ancient Israel.

Essays on Related Topics: