Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Niddah (Menstruation): From Torah to Rabbinic Law

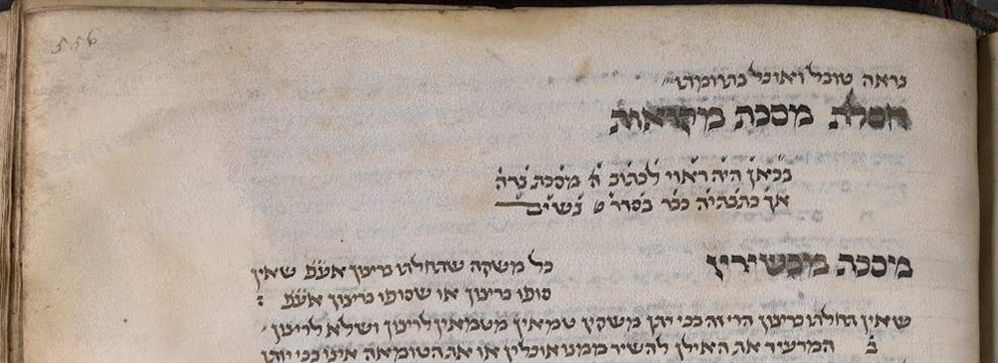

The laws of Niddah – Seder Birkat ha-mazon. Zürich, Braginsky Collection, B351, f. 10v Hamburg and Altona, copied and illustrated by Jakob ben Juda Leib Schammasch · 1741

Biblical law deals with the phenomenon of a woman’s menstrual cycle in two different thematic contexts:

1. Priestly impurity laws (Lev 15);

2. Sexual prohibitions (Lev 18:19 and 20:18).

1. Niddah in the Context of Purity

The former focuses on the impurity (tum’ah) associated with genital fluids of both men (semen) and women (blood).[1] Men and women experiencing such genital emissions are considered to become impure (tame’) themselves, as well as a source of transmitting impurity to another person through various kinds of contact, including sexual contact.

This sort of impurity can be described as “ritual impurity,” since there are no overt moral concerns involved.[2] Rather, men and women experience genital emissions regularly, as part of their biological and sexual lives.

The text does not forbid contact with these fluids; it merely lays out the nature of the impurity contracted, how long it lasts, and how to become purified:

ויקרא טו:יט וְאִשָּׁה כִּי תִהְיֶה זָבָה דָּם יִהְיֶה זֹבָהּ בִּבְשָׂרָהּ שִׁבְעַת יָמִים תִּהְיֶה בְנִדָּתָהּ וְכָל הַנֹּגֵעַ בָּהּ יִטְמָא עַד הָעָרֶב… טו:כדוְאִם שָׁכֹב יִשְׁכַּב אִישׁ אֹתָהּ וּתְהִי נִדָּתָהּ עָלָיו וְטָמֵא שִׁבְעַת יָמִים וְכָל הַמִּשְׁכָּב אֲשֶׁר יִשְׁכַּב עָלָיו יִטְמָא.

15:19 When a woman has a discharge, her discharge being blood from her body, she shall remain in her impurity seven days; whoever touches her shall be unclean until evening…. 15:24 And if a man lies with her, her impurity is communicated to him; he shall be unclean seven days, and any bedding on which he lies shall become unclean.

The text does not prohibit a man having sex with a menstruant; it notes instead that such contact causes the man to contract the same sort of impurity as the woman has (i.e., he has the impurity of niddah for seven days).

Maintaining the Purity of the Sanctuary (Mishkan)

This text is concerned about the possible profanation of the sanctuary if an impure person were to appear there and come in contact with the holy. For this reason, until they are purified, people who experience these various emissions or who come in contact with these fluids are temporarily excluded from the sanctuary/Tabernacle (mishkan), since contaminating the place where God dwells would be a severe offense:

ויקרא טו:לא וְהִזַּרְתֶּם אֶת בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל מִטֻּמְאָתָם וְלֹא יָמֻתוּ בְּטֻמְאָתָם בְּטַמְּאָם אֶת מִשְׁכָּנִי אֲשֶׁר בְּתוֹכָם.

Lev 15:31 You shall put the Israelites on guard against their impurity, lest they die through their impurity by defiling My Tabernacle which is among them.

Consequently, this biblical chapter’s primary concern is with processes of ritual purification to allow people eventually to approach the sanctuary again; much of the chapter is comprised of these rituals.

2. Niddah as a Sexual Prohibition

Leviticus 18 and 20 are concerned with sexual transgression and maintaining Israel’s status as holy and permitted to live on God’s land. Their focus is upon Israel as a people and not upon the sanctuary. Sex with a menstruating woman is listed as one of many forbidden sexual acts, punishable in Lev 20 by “extirpation” (karet) from “among their people.”

ויקרא יח:יט וְאֶל אִשָּׁה בְּנִדַּת טֻמְאָתָהּ לֹא תִקְרַב לְגַלּוֹת עֶרְוָתָהּ.

Lev 18:19 Do not come near a woman during her menstrual impurity to uncover her nakedness.

ויקרא כ:יח וְאִישׁ אֲשֶׁר יִשְׁכַּב אֶת אִשָּׁה דָּוָה וְגִלָּה אֶת עֶרְוָתָהּ אֶת מְקֹרָהּ הֶעֱרָה וְהִיא גִּלְּתָה אֶת מְקוֹר דָּמֶיהָ וְנִכְרְתוּ שְׁנֵיהֶם מִקֶּרֶב עַמָּם.

Lev 20:18 If a man lies with a woman in her infirmity and uncovers her nakedness, he has laid bare her flow and she has exposed her blood flow; both of them shall be cut off from among their people.

While Lev 18:19 does draw on the language of impurity,[3] the differences in the legislative tone and legal treatment of menstruation between Leviticus 18 and 20 on one hand and Leviticus 15 on the other are palpable. In Leviticus 15, the Sanctuary (whether the wilderness Tabernacle or the Jerusalem Temple) is the institutional reference point, and polluting the Sanctuary is the only serious concern expressed. The sexual transgressions of Lev 18 and 20, on the other hand, are not dependent on any institutional context; they are categorically prohibited.

Priestly Purity vs. People’s Holiness

Biblical scholars explain the difference between the two contexts as a difference of sources. The Priestly source (P), of which Leviticus 15 is a part, is concerned about purity and the sanctuary, whereas the (later) Holiness source (H), of which both Leviticus 18 and 20 are part, is concerned about the sanctity of the people. Accordingly, both sources have different goals, and in cases such as this, different legislation.[4]

The talmudic rabbis, of course, treat the Torah as a unitary corpus. Their treatment of niddah, which shifts over time, reflects this tension between primarily seeing the laws as regulating purity (with P) or as regulating sex (with H).

The Order of Purities – The Mishnah’s Approach to Niddah

The Mishnah, the earliest rabbinic collection of rabbinic halakhic teachings, places the laws of menstruation, found in Tractate Niddah,[5] in its Order of Toharot (טהרות) “Purities,” along with other relevant tractates, such as Zavim on male genital fluids, and Mikva’ot on the construction and rabbinic institutionalization of the mikvah (ritual bath), to name but a few.[6]

The Mishnah is thus categorizing the laws of niddah in the manner of the Priestly text in Leviticus 15 by making impurity the organizational context for hilkhot niddah (“the laws of the menstruant woman”).[7] For the Tannaim (the rabbinic sages of the period of the Mishnah), the observance of ritual impurity and purification constituted an essential part of their halakhic piety, and niddah, just like the biblical zav, was part of that.[8]

At the same time, the Tannaim did not ignore the sexual prohibitions associated with niddah, found in the Holiness legislation in Leviticus 18 and 20, and the centrality of this aspect of the niddah laws began to gain prominence in halakhic discourse during this period.

Sexual Transgression – The Talmud’s Approach to Niddah

By the time the sages formulated and redacted the gemara, i.e., the traditions of the Amoraim and their discussions as they are organized in the Talmud, the sexual prohibition had become by far the dominant theme.[9] In fact, the only tractate in the mishnaic Order of Toharot that even has a talmudic discussion accompanying it is Tractate Niddah,[10] perhaps because the purity laws were no longer relevant by this time. And thus, by the time of the Amoraim, the discourse about niddah shifts from the Priestly emphasis on purity to the Holiness emphasis on sex.[11]

Eliding the Categories

The rabbis understand the two halakhic realms of sexual prohibition and ritual impurity to be interdependent. Therefore, they often apply their innovative rulings to both aspects of niddah laws, regardless of where they learn these innovations from. The elision of these two realms leads to an important change in how the prohibition of sex with a niddah is conceptualized.

The Prohibition of Sex with a Menstrually Impure Woman

The Mishnah assumes that women must go to the mikvah before they resume sexual relations with their husbands.[12] This is based on a number of assumptions that are not in the Torah.

- Washing for purification – the rabbis assume that women must wash (ר.ח.צ) in water to purify themselves after niddah (Lev 15:16, m. Mikva’ot 8:1,5), just as the Torah requires a man to do after ejaculation and a woman after sex with her husband (Lev 15:18, m. Mikva’ot 8:4). But such a requirement is never stated explicitly in the Torah with regard to menstruation.[13]

- Mikvah – The rabbis assume this washing must be in a mikvah though the Torah never says this.[14]

Purification Required for Sex?

Even if we assume that Leviticus 15 wishes women to immerse in a mikvah as part of purification, which is doubtful from a biblical perspective, this would be part of a Priestly purification ritual, to allow her to come in contact with holy objects and the sanctuary. In other words, immersion would remove her state of impurity, which began with her menstruation.

In contrast, the prohibition in Leviticus 20 is not about “menstrual impurity” but about sex with a menstruant woman, and thus, the text emphasizes the taboo of contact with her blood: “he has laid bare her flow and she has exposed her blood flow” [15] (אֶת מְקֹרָהּ הֶעֱרָה וְהִיא גִּלְּתָה אֶת מְקוֹר דָּמֶיהָ). Once the blood has cleared, it would seem that the husband and wife are permitted to resume sexual relations.

Once the rabbis connected the two systems into one, however, the prohibition against sex with a menstruant woman was transformed into one against sex with a woman with the status of menstrual impurity.[16] With that, the idea of mikvah making a woman pure for her husband was created.

Appendix

Checking for Blood and the Use of Cloths

A subtler example of how practices surrounding the prohibition of sex with a niddah were transformed by concepts originally connected with purity laws can be seen in the development of the rabbinic requirement for a woman to check whether she is menstruating.

Mishnah Niddah opens with the concern that a woman may have begun her menstrual period without having realized it—the Torah expresses no such concern—and consequently may have touched Temple-related food items in the meantime. But if this is the case, how far back should we apply this “retroactive impurity” and declare the holy food that she has touched to be impure?[17]

Hillel suggests that all the holy food is impure going back to the last time she checked (or “took notice,” פקידה) to see if she was menstruating, even if it was days earlier.[18] The Mishnah does not explain what such a notice taking entails, but the implicit expectation is that a woman would be checking herself consistently to see if she was menstruating, and thus protect the holy Temple-food under her care from possible impurity.

Checking Before Sex

Unsurprisingly, the Mishnah records that certain women began checking before sex as well (m. Niddah 2:1):

הצנועות מתקנות להן שלישי לתקן את הבית.

Modest women use a third [wiping cloth][19](before sex) to “make sure their house is in order.”

The practice makes intuitive sense, since if a woman is taught to be concerned about touching holy food while unknowingly a niddah, should she not worry that she may unknowingly have sex while a niddah? In fact, by the end of the Mishnaic period, this custom of modest women turned into a rabbinic requirement parallel to the requirement to check before touching holy food (m. Niddah 1:7):

ופעמים צריכה להיות בודקת בשחרית ובין השמשות ובשעה שהיא עוברת לשמש את ביתה.

[A woman] must check herself twice daily: in the morning and at dusk, as well as whenever she prepares herself for intercourse with her husband.

This Mishnah, which reflects a later stage of halakhic development than 2:1, treats all these checks as rabbinic requirements.[20] We see here a multi-stage process: What was once only a purity-based concern, retroactively making holy Temple-food impure, developed into a concern about sexual transgression for some women, and the practice of checking for blood before working with holy food inspired the practice of checking before sex. Eventually, both were established in Mishnah Niddah 1:7 as parallel halakhic requirements.

Post-Coital Wiping Cloths

In discussing Hillel’s rule that impurity is extended retroactively to the most recent check, the Mishnah adds a mitigating factor (m. Niddah 1:1):

והמשמשת בעדים הרי זו כפקידה

And if a woman has intercourse using wiping-cloths, this is like as a check.

The phrasing “like a check” (כפקידה) makes it clear that checks for holy food and “wiping-cloths” for sex are different. A later Mishnah (Niddah 2:1) explains what “intercourse using wiping-cloths” means:

דרך בנות ישראל משמשות בשני עדים אחד לו ואחד לה.

It is the way of Jewish women to use two wiping cloths (after sex), one for her and one for him.[21]

Why would they use wiping cloths after intercourse? The next Mishnah (2:2) explains that they are used to determine whether the couple unintentionally had sex while she was menstruating:

נמצא על שלו טמאין וחייבין קרבן נמצא על שלה אותיום טמאין וחייבין קרבן נמצא על שלה לאחר זמן טמאים מספק ופטורים מן הקרבן:

If [blood] appears on his cloth, they are both impure and required to offer a sacrifice. If [blood] appears on hers [after wiping] immediately, they are both impure and required to offer a sacrifice. If [she only wiped] later, they are both possibly impure and exempt from offering sacrifices.

This explanation is surprising. If transgression is the concern, then the woman should be required to check before, something that this same mishna claims only “modest women” would do (as we have seen above). Moreover, designing an entire halakhic practice just to determine whether a person accidentally sinned in the past is unusual. Consequently, this explanation seems like a post-facto rationalization.

Instead, I suggest that the wiping cloths were originally unconnected to niddah. Rather, they were used to wipe off semen since contact with semen makes a person impure (Lev 15:16-18),[22] and it would need to be completely removed before going to mikvah.

A strong piece of evidence that this is the original point of the wiping comes from Mishnah Mikva’ot 8:4:

האשה ששמשה ביתה וירדה וטבלה ולא כבדה את הבית כאילו לא טבלה בעל קרי שטבל ולא הטיל את המים כשיטיל את המים טמא.

A woman who had sex (lit. “served her house”) and goes to immerse herself but has not cleaned out her vagina – it is as if she has not immersed. A man who has ejaculated and immerses himself but did not urinate [in between], when he urinates he is impure

The practice noted in Mishnah Niddah (2:1) of using wiping cloths immediately after sex likely reflects the same concern as this Mishnah, to remove all traces of semen before immersion.

Thus, the Mishnah (Niddah 1:1) teaches that even though the woman was not using a wiping cloth to check for blood but merely to clean herself of semen, this would count as a check (כפקידה), and the lack of blood on the wiping cloth would be evidence that she had not begun menstruating by that point.

As the relative importance of the purity laws and the sexual laws regarding niddah began to shift, this practice of “intercourse using wiping cloths,” which was originally connected to purity laws, was reinterpreted as relevant to the prohibition of sex during menstruation, even though the only connection the Mishnah could find was the counter-intuitive “checking to see if they had transgressed.”

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

April 18, 2018

|

Last Updated

April 12, 2024

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Footnotes

Prof. Charlotte Elisheva Fonrobert is Associate Professor of Jewish Studies in the Department of Religious Studies at Stanford University and is (returning) Director of Stanford’s Taube Center of Jewish Studies. She received her Ph.D. from Berkeley GTU, Center for Jewish Studies. She is the author of Menstrual Purity: Rabbinic and Christian Reconstructions of Biblical Gender, and co-editor of The Cambridge Companion to the Talmud and Rabbinic Literature and Talmudic Transgressions.

Essays on Related Topics: