Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Relating Truthfully to Morally Problematic Torah Texts

Decorated initial-word panels: on f.11 two citations from Deuteronomy 1:5 and 4:44, on f. 12, the beginning of Maimonides’ introduction to his Mishneh Torah with a citation from Psalms 119:6. Image taken from Lisbon Mishneh Torah, 1450 – 1474. British Library Harley Collection

Morally Problematic Laws

The problem of unjust or immoral laws in the Torah and halacha is pervasive. This is true of any legal system that continues over time in radically different cultures. The Torah in particular contains quite a number of laws that are problematic for later readers.[1]

The mitzvah of cherem, i.e., the requirement to slaughter the entire population of Canaanites and Amalekites, is a clear example of such a problem (Deut 7:2, 20:16-18, 1Sam 15). Another is capital punishment for religious infractions (Exod 31:14, Num 15:35), including the stoning to death of a young maiden at the door of her father’s house for the crime of premarital relations (Deut 22:21).[2]

We find similarly problematic laws in rabbinic tradition as well, such as the prohibition to ever free one’s gentile slave (b. Berachot 47b) or the mitzvah to kill heretics by pushing them down a well, codified by Maimonides (Mishneh Torah, “Laws of Murder and Protection of Life,” 4:10):

המינים, והם עובדי עבודה זרה מישראל, או העושה עבירות להכעיס אפילו אכל נבילה או לבש שעטנז להכעיס הרי זה מין, והאפיקורוסין, והן שכופרין בתורה ובנבואה, מישראל, מצוה להרגן, אם יש בידו כח להרגן בסייף בפרהסיא הורג, ואם לאו יבוא עליהן בעלילות עד שיסבב הריגתן. כיצד, ראה אחד מהן שנפל לבאר, והסולם בבאר, קודם ומסלק הסולם ואומר לו הריני טרוד להוריד בני מן הגג ואחזירנו לך, וכיוצא בדברים אלו.

Sectarians, that is, Israelite worshipers of foreign gods, or one who transgresses commandments defiantly, even if he [merely] eats non-kosher meat or wears shaatnez defiantly, this is a sectarian. Heretics, that is, those who deny [the divine origin of] the Torah or the Israelite prophets – it is a mitzvah to kill them. If one has the power to kill them with a sword in public, he should kill him. If not, he should sneak up on him until he can cause them to be killed. How? If he sees one of them has fallen into a pit, and there is a ladder in the pit, he should remove the ladder and tell him “I need to get my son off of a roof, then I will return it,” and similar strategies.[3]

Invoking Meta-Halachic Principles

The rabbis of the Talmud inherited the written Torah and even much of the Oral Torah (halacha), at least in broad strokes. Aware that these corpora contained morally problematic requirements, the Rabbis devised a series of “second order” principles, which they used to modify primary legislation on an ethical basis, and to govern the relationships of Jews to those outside the bond of faith or peoplehood. These are now frequently termed “meta-halachic” principles, a term coined by Eliezer Goldman (1918-2002).[4] These principles include:

1. משום איבה mishum eiva (“on account of hatred”) — This principle was invoked to avoid carrying out actions that though halachically correct, would offend people or cause strife.[5] Halacha forbids a Jewish woman being a wet-nurse or a midwife for gentile babies, but the rabbis permitted this anyway to avoid getting the gentiles angry (b. Avodah Zarah26a). Similarly, Jews are not supposed to treat animals owned by non-Jews, they should do so anyway to avoid getting gentiles angry (b. Baba Metzia 32b).

2. דרכי שלום darkei shalom (“the ways of peace”) — This is the inverse principle to mishum eiva: we require certain behaviors, even if they are not what pure halacha would like or demand, to avoid quarrels or make people feel good. We allow needy idolaters to gather gleanings (m. Gittin 5:8),[6] and we greet them (m. Shevi’it 4:3)[7] even though this may prompt them to invoke their gods, all in the interest of peace.

3. תקון עולם tiqqun olam (“establishing the world aright”) — This is, in its strict sense, an “extra-legal” measure introduced within the community to avoid impossible situations. The rabbis forbade paying exorbitant ransoms for Jewish captives, to avoid encouraging brigands (or governments) to kidnap more Jews. Similarly, they forbade breaking captives out of captivity so as not to cause a backlash against other captives, like keeping them in chains (m. Gittin 4:6).[8] In recent times, this same term has become widely used, especially but not exclusively by liberal Jews, in a much broader sense, to articulate Jewish responsibility toward the world in general.

4. דרכי נועם darkei noam (“the ways of pleasantness”)[9] — The rabbis use this to avoid insisting on certain strict legal practices if they have unpleasant consequences. For example, Beit Shammai and Beit Hillel debate about whether certain widows need to perform chalitzah (the ritual that dissolves a levirate bond with her late husband’s brother) or not.[10] The Talmud asks what should be done with a woman who remarried thinking that she does not require chalitzah, but is then told that she does according to one of these authorities (b. Yebamot 15a).

הכי קאמר: הנך צרות דב”ה לב”ש היכי נעביד להו? ליחלצו, מימאסי אגברייהו! וכי תימא לימאסן, דרכיה דרכי נועם וכל נתיבותיה שלום.

This is the meaning [of the objection “what shall we do”]: How shall we, according to Beth Shammai, proceed with those rivals [who married in accordance with the rulings] of Beth Hillel? Should they be asked to perform the chalitzah, they would become despised by their husbands (for having been bound to another man while he was married to her); and should you say, “Let them be despised,” [it could be retorted:] “Her [the Torah’s] ways are ways of pleasantness and all her paths are peace.”

5. 'קדוש ה Kiddush Hashem (“sanctifying God’s name”) — This refers to behaving in such a manner as to bring credit to God, even when not halakhically required. The Talmud records a discussion in a baraita of how to handle a case in which a Jew and a gentile are in litigation against each other (b. Bava Qama 113a):[11]

ישראל וכנעני (אנס) שבאו לדין, אם אתה יכול לזכהו בדיני ישראל – זכהו ואמור לו: כך דינינו, בדיני כנענים – זכהו ואמור לו: כך דינכם, ואם לאו – באין עליו בעקיפין, דברי ר’ ישמעאל; ר”ע אומר: אין באין עליו בעקיפין, מפני קידוש השם.

Where a suit arises between an Israelite and a heathen, if you can justify the former according to the laws of Israel, justify him and say: “This is our law”; so also if you can justify him by the laws of the heathens justify him and say [to the other party:] “This is your law”; but if this cannot be done, we use subterfuge to circumvent him. This is the view of R. Ishmael, but R. Akiva said that we should not attempt to circumvent him on account of the sanctification of the Name.

The Talmud points out that the implication of R. Akiva’s statement is that it would be all right to defraud this gentile if it weren’t for the need to sanctify God’s name, and thus, we see what ethical hitch this principle has come to solve.

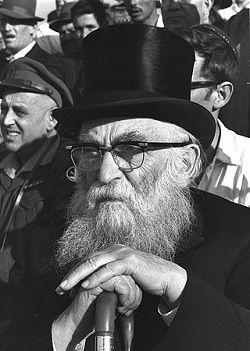

Meta-Halacha as an Ideal, Not a Concession: R. Isser Yehudah Unterman

The late Chief Rabbi of Israel, Isser Yehudah Unterman (1886-1976), viewed these meta-halakhic principles as follows:

The laws of darkei shalom flow from the moral fount of the holy Torah whose “ways are the ways of pleasantness and all her ways are peace” (Proverbs 3:17); they were instituted by our sages of old in their great wisdom and are obligatory upon all of us. They have the power to determine the interpretation of halacha and to permit things that the sages forbade. We find that they even permitted transgression of some Torah prohibitions mishum eiva, though with regard to the sabbath they permitted only transgression of rabbinic law … unless the situation was dangerous [in which case it overrides even Torah law].[12]

In R. Unterman’s interpretation, דרכי שלום and the associated concepts of משום איבה and דרכיה דרכי נועם are not merely concessions, but principles for determination and modification of existing laws. That is, halacha itself is in certain circumstances defined by the overriding moral imperative to seek peace and avoid conflict and causing pain.

Do these pragmatic principles and applications of abstract values, then, more or less solve the ethical conundrums inherent in halacha as implied by R. Unterman? I am afraid not.

Still on the Books Means Still from God

As noted above, the laws remain on the books, and this includes their very unpleasant theoretical applications and philosophical underpinnings. For example, even though halakhic authorities are in agreement that nowadays we should not be killing heretics, this is only because of a legal loophole: in the best of worlds, so to speak, we should be doing just that. Are we really looking forward to the time when the shekhina (divine presence) will again be manifest so that we can allow them to die in pits? Do we hope for the reestablishment of the Sanhedrin so we can again stone Sabbath violators and wayward maidens to death? I imagine most of us would not be looking forward to such a world.

Moreover, if we affirm that the problematic verses and halakhot all come literally and directly from God to Moses, how does it help to say that we can devise sundry principles and midrashic reinterpretations to avoid having to actually carry them out. Does God want us to carry them out, at least in theory? Does God really want us to wiggle our way out of them?

Finally, we should note the limited practical effect of this kind of apologetic approach; it leaves open the possibility that one day somebody—a Baruch Goldstein or a Yigal Amir—will notice what is written, and will act upon its plain sense. Criticism will be muted, because the rabbis and yeshiva teachers themselves, have not confronted the morally problematic nature of texts and guided their students on how to handle them.

These are all serious problems.

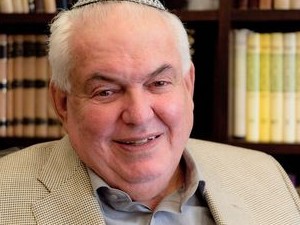

R. David Hartman – The Need for Natural Morality

Few have struggled with the moral conflict between tradition and modernity more boldly than the late R. David Hartman. In a passionate address to the Jerusalem Fellows’ Colloquium on 28 December 1995 he reflected upon the assassination of Prime Minister Yitzchak Rabin on 4 November that year by Yigal Amir, a young man raised in some of the finest Israeli religious institutions:

I am not calling for religious neutrality. I am calling for alternative passions… As a Jewish philosopher I feel this intuitively, and I know it is correct, without a posek, without a Rambam, without anything.

I am straight with you – I have no authoritative position in the tradition to validate this. What validates this is my own sense of human decency… I want to get away from needing validations, or foundational texts, in order to confirm moral intuitions. I believe that moral intuitions grow from some sort of decency…

So people ask me, “What is the foundation for your morality? What is the source of it?” I have no source, I don’t know. It is the accumulated experience of what decent people around the world have come to understand what civilized behavior is all about. I have no other source. A posek? A Shakh?[13] No. I don’t have to look at books to find out what a decent person is about …

…[T]he meaning of being a religious Jew in the modern world is to live with the risks of living with numerous vocabularies and multiple frames of reference. There is no more security.[14]

This quotation fits the model that Hartman has developed at length in numerous books and articles: a theory of “two covenants.” One, the creation covenant, was made with all humanity; it depends on some sort of innate, natural law, written in people’s hearts. The second, at Sinai, was with Israel only, and is based on a revealed code of law that supplements, rather than displaces, the innate understanding of right and wrong on which the first covenant is based. The Sinai covenant cannot supersede the creation covenant, and thus we must modify or protest any halakhot (=Sinai covenant) that contradict natural morality (=creation covenant).

Unethical Sacred Literature?

This may justify Hartman in living in two worlds at once, what he calls “alternative channels of value,” a world of ethics and a world of halacha, but it does not resolve our problem. Most significantly, for our purposes, Hartman – and he realized this – has not solved the basic question, which is how to continue reading texts as sacred literature when we reject them from an ethical perspective. What he has done is to show us in theory—and during his lifetime by personal example—how to acknowledge and live with the problem.

Avoiding Self-Deception and Reformulating Our Doctrines

It may be that earlier generations, when interpreting texts against their plain sense or divining legal loopholes that made such texts inapplicable, thought they were revealing their “true meaning.” This possibility has been closed to us by the development of historical-critical methods of textual study, which suggest that these true meanings are later interpretations and do not reflect these texts’ earliest meanings. And yet, to maintain or fealty to Torah and continuity with tradition, we must do something to “reclaim” these laws and passages.

Torah Min HaShamayim and Halacha Mi-Sinai

The conundrum becomes clearer if we present it in terms of dogma or doctrine. We are familiar with the rabbinic doctrine of the two Torahs. The midrash expresses this as a gloss on the word תורות (“instructions” or “Torahs”) in the plural, found in Lev 26:46 (Sifra, “Bechukotai,” 2:8.13):

והתורות מלמד ששתי תורות ניתנו להם לישראל אחד בכתב ואחד בעל פה.

“And the torot,” – This teaches us that two Torahs were given to Israel: the written Torah and the Oral Torah.

The written Torah means the Pentateuch. The oral Torah means the laws that make up the category called דאורייתא or “Torah law” in the Mishnah and Talmud. In other words, the text is saying that God transmitted the entire Pentateuch as well as the system of halacha to Moses in the Sinai wilderness. This claim is enshrined in the dual doctrines of Torah min Ha-Shamayim, that the Torah (=Pentateuch) comes from heaven, and Torah mi-Sinai, that the halacha (the laws of the Pentateuch and the Oral Torah) was communicated to Moses at Sinai and passed down faithfully throughout the ages.[15]

Can God Dictate Unethical Laws?

If we are to take these doctrines literally, and avoid the self-deception of radically reinterpreting these ancient texts, we will be stuck in the extremely problematic position of having to affirm that God literally commanded morally unsound laws.

Thus, I do not believe that a satisfactory solution is possible if we stick to the idea that these halakhot, whether in the Torah or part of the Oral Torah, were literally dictated by God to Moses. This means that we must radically reformulate the doctrines of Torah min ha-Shamayim and Torah mi-Sinai. We need an interpretation that will uphold the status of sacred texts and traditions without suggesting that their precise wording is dictated by God and eternally binding.

The Literal or Metaphorical Voice of God: Lichtenstein vs. Borowitz

Some years ago, R. Aharon Lichtenstein and R. Eugene Borowitz locked horns over the relationship between ethics and halacha,[16]which was the secondary outcome of a deep disagreement about Torah min ha-Shamayim.

For R. Lichtenstein, speaking as an Orthodox rabbi, halacha was literally the “voice of God”—a transcendent God—who commanded on a specific historical occasion, and commanded specific laws.

For R. Borowitz, speaking as a liberal rabbi committed to the historical-critical approach, Torah min Ha-Shamayim was a distant metaphor for a social reality, of the people Israel in covenantal relationship with its God, while halacha was a transient formulation of this relationship.

The Orthodox Need to Go Beyond Metaphor

Borowitz’s image of Torah min HaShamayim as a metaphor is attractive, and yet it is not possible for the Orthodox Jew to interpret this doctrine or that of Torah mi-Sinai in the same manner as Borowitz. The terms may in fact be metaphors, but Orthodox Jews can hardly leave it there. At the very least, these doctrines must validate a specific text (the Five Books of Moses) and the received system of halacha (the Oral Torah).

To be both true to the doctrines and true to our moral values, it is necessary to say, for instance, “Yes, these difficult texts in the Torah are part of Torah min Ha-Shamayim, that is, they are part of the document which stands as the historical expression of the myth of Israel’s encounter with God, and which cannot be altered, for it—the document—is a fact of history. But this does not bind us to specific provisions which run counter to our moral convictions.”

The same is true of rabbinic halakhot, which have been codified in the Mishnah and Talmud, and are part of Torah mi-Sinai, the system of practice which interprets and accompanies the Torah, unique to rabbinic Judaism, and which partakes in the same foundation myth. As with the Pentateuch, Rabbinic literature should not go through an expunging, these texts too are “facts of history.” But we cannot be bound by the ethically problematic provisions found within the Rabbinic corpus either.

Torah min Ha-Shamayim and Torah mi-Sinai as Foundational Myths

For the above reasons, I prefer to go beyond the language of metaphor and to describe Torah min Ha-Shamayim and Torah Mi-Sinai as foundational myths.[17] A myth may be retained unchanged in a culture long after anyone understands it as a factual account of events, because it forms, or at least contributes to the formation of, that culture. Whether its elements are regarded as metaphors or historical facts will depend on the worldview, scientific understanding etc. of those who tell it or hear it.[18]

Presenting Torah min Ha-Shamayim and Torah mi-Sinai as foundational myths can be of great utility. Torah min Ha-Shamayim, the idea that the Torah originated in heaven and was revealed to Israel, projects the (metaphorical) image of a book being handed out of the sky to convey the deeper but ineffable truth of divine communication. It is complemented by the concept of Torah mi-Sinai, which grounds rabbinic halacha in the primordial story of God’s encounter with Israel in the remote past.

The location of these images in an account of a revelation situated beyond the limits of earthly history (and thus liberated from historical criticism) powerfully articulates a formative idea of Jewish society, namely, the relationship of God, Torah (in both senses), and Israel.

Creating Space Between God and Torah

Granted, in the above articulation, the morally problematic laws in Torah and halacha are kept “on the books,” and remain as blemishes within Judaism’s theoretical structure; nevertheless, they are no longer of practical import. More importantly, recognizing that doctrines such as Torah min Ha-Shamayim and Torah mi-Sinai are foundational myths, not historical claims, creates space between the divine source and the concrete formulation.

Thus, we can make some peace with the idea that as ethical notions evolve, some of the laws codified in earlier stages will seem problematic to us and must be left behind as relics of a different age with a different—and to our minds problematic—worldview. It could well be that our own, “enlightened,” moral views will one day be outmoded; let us hope that our descendants will feel bound not by our frail words, but by the robust spiritual tradition to which we attempt, from within our limited perspective, to give voice.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

January 24, 2017

|

Last Updated

February 7, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

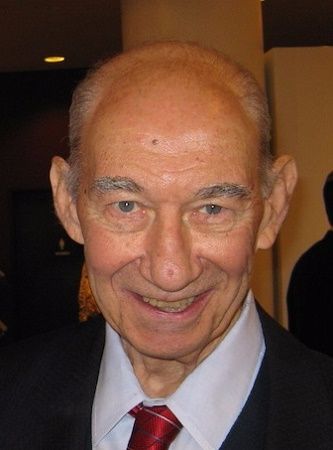

Dr. Rabbi Norman Solomon was a Fellow (retired) in Modern Jewish Thought at the Oxford Centre for Hebrew and Jewish Studies. He remains a member of Wolfson College and the Oxford University Teaching and Research Unit in Hebrew and Jewish Studies. He was ordained at Jews’ College and did his Ph.D. at the University of Manchester. Solomon has served as rabbi to a number of Orthodox Congregations in England and is a Past President of the British Association for Jewish Studies. He is the author of Torah from Heaven.

Essays on Related Topics: