Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Aaron’s Flowering Staff: A Priestly Asherah?

Full-page miniature of the twelve rods with the flourishing rod of Aaron in the middle. F. 519v from ‘The Northern French Miscellany’ France, 1277-1286. British Library

The Flowering Staff Test

Following a number of challenges against the authority of Moses and Aaron,[1] YHWH tells Moses to gather the staffs of the leader of each of the twelve tribes, as well as (or including) that of Aaron, and to place them in the Tent of Meeting.

במדבר יז:כ וְהָיָה הָאִישׁ אֲשֶׁר אֶבְחַר בּוֹ מַטֵּהוּ יִפְרָח וַהֲשִׁכֹּתִי מֵעָלַי אֶת תְּלֻנּוֹת בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל אֲשֶׁר הֵם מַלִּינִם עֲלֵיכֶם.

Num 17:20 The staff of the man whom I choose shall sprout, and I will rid Myself of the incessant mutterings of the Israelites against you.

Moses explains the test to the people and puts the staffs into the Tent of Meeting overnight.

במדבר יז:כג וַיְהִי מִמָּחֳרָת וַיָּבֹא מֹשֶׁה אֶל אֹהֶל הָעֵדוּת וְהִנֵּה פָּרַח מַטֵּה אַהֲרֹן לְבֵית לֵוִי וַיֹּצֵא פֶרַח וַיָּצֵץ צִיץ וַיִּגְמֹל שְׁקֵדִים.

Num 17:23 The next day Moses entered the Tent of the Testimony,[2] and there the staff of Aaron of the house of Levi had sprouted: it had brought forth sprouts, produced blossoms, and borne almonds.[3]

Moses shows the people what happened with the staffs, after which Yhwh commands him:

במדבר יז:כה הָשֵׁב אֶת מַטֵּה אַהֲרֹן לִפְנֵי הָעֵדוּת לְמִשְׁמֶרֶת לְאוֹת לִבְנֵי מֶרִי…

Num 17:25 Put Aaron’s staff back in front of the Testimony, to be kept as a sign to defiant people…

A Stylized Tree

Aaron’s staff (מַטֶּה) produced:

- Buds [4](פֶּרַח)

- Blossoms [5](צִיץ)

- Almonds [6] (שְׁקֵדִים)

Despite the overall image of a tree, leaves are not mentioned, nor are roots and branches. Thus, the description is more of a stylized tree than of a tree. The precise combination of buds, blossoms, and almonds does not occur anywhere else in the Bible,[7] which brings up the question: Why did this author have Aaron’s staff undergo this particular transformation?[8]

An Etiological Narrative

As observed by a number of scholars,[9] the culmination of the narrative in the permanent placement of the staff in the sanctuary indicates that the narrative is etiological: it provides an origin story for an object that was familiar to its original audience, presumably an object that resembled a flowering staff and was located in the sanctuary.[10] I believe that from archaeology and other biblical texts we can identify the object in question as another familiar stylized tree, the asherah.

Asherah—A Stylized Tree

An asherah (אֲשֵׁרָה, pl. asherim, אֲשֵׁרִים) is a class of cultic objects mentioned some forty times in the Tanakh. In a few instances, the word asherah seems to refer to a deity (Judg 3:7; 1 Kgs 15:13 [≈ 2 Chr 15:16]; 1 Kgs 18:19; 2 Kgs 23:4), causing many scholars to posit a connection between the asherah and the Ugaritic goddess Athirat.[11] Whether this is correct or not, in the vast majority of cases, the biblical text is referring to a physical object and not a goddess.

The biblical asherah is usually identified by scholars as a wooden, staff-like, “stylized tree.”[12]In fact, John Day suggests that the rhabdoi (ῥάβδοι), “staves,” dedicated by the Phoenicians and Egyptians to their Gods, according to the testimony of Philo of Byblos (Eusebius, Praeparatio Evangelica 1.10.11), are akin to what the Tanakh calls asherim.[13] The word rhabdos (ῥάβδος) is precisely the term used by the Septuagint when referring to Aaron’s staff.

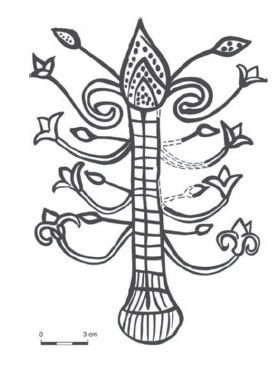

A prime Israelite example of a depiction of such a “stylized tree” is a red-ink drawing on Pithos A from Kuntillet ‘Ajrud [Figure 1]. This drawing may in fact depict the very asherah set up by Ahab in Samaria (1 Kgs 16:33; 18:19; 2 Kgs 17:16), which is stated to have been extant during the reign of Jehoahaz (2 Kgs 13:6)[14] around the time of the drawing’s creation.[15]

|

|

It is difficult to imagine a more precise pictorial representation of the object described verbally in the Torah’s account than this drawing. The central element of the drawing plainly resembles a staff.[16] It is adorned with six buds alternating with eight blossoms. And at the top are two elements shaped like almonds in the shell and speckled with dots that match the pockmarks typical of these shells [Figure 2].[17]

The Asherah in Jerusalem

Generic asherim are portrayed as having been placed ubiquitously at local cultic sites, whether Canaanite (Exod 34:13; Deut 7:5; Deut 12:3), Israelite (1 Kgs 14:15; 2 Kgs 17:10), or Judahite (1 Kgs 14:23; Isa 17:8; 27:9; Jer 17:2; Mic 5:13; 2 Chr 14:2; 17:6; 19:3; 24:18; 31:1).[18]

The book of Kings attests that there was a particular, prominent asherah in the Jerusalem Temple. The author of Kings sees this fact as something negative, and blames it on the sinful King Manasseh who וַיַּעַשׂ אֲשֵׁרָה “made an asherah” (2 Kgs 21:3) and:

מלכים ב כא:ז וַיָּשֶׂם אֶת פֶּסֶל הָאֲשֵׁרָה אֲשֶׁר עָשָׂה בַּבַּיִת אֲשֶׁר אָמַר יְ־הוָה אֶל דָּוִד וְאֶל שְׁלֹמֹה בְנוֹ בַּבַּיִת הַזֶּה וּבִירוּשָׁלִַם אֲשֶׁר בָּחַרְתִּי מִכֹּל שִׁבְטֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל אָשִׂים אֶת שְׁמִי לְעוֹלָם.

2 Kgs 21:7 He placed the sculptured image of Asherah that he made in the House concerning which YHWH had said to David and to his son Solomon, “In this House and in Jerusalem, which I chose out of all the tribes of Israel, I will establish My name forever.”[19]

Whether the Temple’s asherah really was made by Manasseh, or whether the Deuteronomistic author of Kings is simply pinning a problematic item from the Temple’s past on a hated king, is hard to say. Either way, the book of Kings goes on to say that one of the book’s main heroes, Manasseh’s pious grandson, Josiah, destroyed the asherah and its implements (כֵּלִים, 23:4), and purged the Temple of them:

מלכים ב כג:ו וַיֹּצֵא אֶת הָאֲשֵׁרָה מִבֵּית יְ־הוָה מִחוּץ לִירוּשָׁלִַם אֶל נַחַל קִדְרוֹן וַיִּשְׂרֹף אֹתָהּ בְּנַחַל קִדְרוֹן וַיָּדֶק לְעָפָר וַיַּשְׁלֵךְ אֶת עֲפָרָהּ עַל קֶבֶר בְּנֵי הָעָם.כג:ז וַיִּתֹּץ אֶת בָּתֵּי הַקְּדֵשִׁים אֲשֶׁר בְּבֵית יְ־הוָה אֲשֶׁר הַנָּשִׁים אֹרְגוֹת שָׁם בָּתִּים לָאֲשֵׁרָה.

2 Kgs 23:6 He brought out the asherah from the House of YHWH to the Kidron Valley outside Jerusalem, and burned it in the Kidron Valley; he beat it to dust and scattered its dust over the burial ground of the common people. 23:7 He tore down the cubicles of the male prostitutes in the House of YHWH, at the place where the women wove coverings for Asherah.

If the asherah in the Jerusalem Temple corresponded to the Kuntillet ‘Ajrud drawing, the author of the account of Aaron’s staff provides an excellent etiological backstory for the object, as the Jerusalem Temple was the home of the Aaronide priesthood.

Deuteronomistic Polemic Against Asherim

Why would the Torah have an etiological tale explaining an asherah in the Temple as a symbol of the Aaronide priesthood? Are not asherim sinful objects hated by YHWH? The answer is: It depends on the source.

Deuteronomy prohibits the use of asherim along with standing stones:

דברים טז:כא לֹא תִטַּע לְךָ אֲשֵׁרָה כָּל עֵץ אֵצֶל מִזְבַּח יְ־הוָה אֱלֹהֶיךָ אֲשֶׁר תַּעֲשֶׂה לָּךְ. טז:כב וְלֹא תָקִים לְךָ מַצֵּבָה אֲשֶׁר שָׂנֵא יְ־הוָה אֱלֹהֶיךָ.

Deut 16:21 You shall not set up (or “plant”) an asherah—any kind of pole (or “tree”) beside the altar of YHWH your God that you may make—16:22 or erect a stone pillar; for such YHWH your God detests.

Moreover, Deuteronomy mandates the destruction of the Canaanites’ asherim along with their altars, standing stones, and sculptures (Deut 7:5; 12:3).

דברים ז:ה מִזְבְּחֹתֵיהֶם תִּתֹּצוּ וּמַצֵּבֹתָם תְּשַׁבֵּרוּ וַאֲשֵׁירֵהֶם תְּגַדֵּעוּן וּפְסִילֵיהֶם תִּשְׂרְפוּן בָּאֵשׁ.

Deut 7:5 You shall tear down their altars, smash their pillars, cut down their asherim, and consign their images to the fire.[20]

We see this same law in Exodus 34, in what some scholars call the Cultic Decalogue:

שמות לד:יג כִּי אֶת מִזְבְּחֹתָם תִּתֹּצוּן וְאֶת מַצֵּבֹתָם תְּשַׁבֵּרוּן וְאֶת אֲשֵׁרָיו תִּכְרֹתוּן.

Exod 34:13 For you must tear down their altars, smash their pillars, and cut down their asherim.[21]

Although this text is not part of Deuteronomy, it certainly shares its perspective on this style of worship.

The book of Kings, part of the Deuteronomistic History, states that King Jeroboam’s dynasty will be removed for its sins, including

מלכים א יד:טו יַעַן אֲשֶׁר עָשׂוּ אֶת אֲשֵׁרֵיהֶם מַכְעִיסִים אֶת יְ־הוָה.

1 Kgs 14:15 Because they have made for themselves asherim and thus provoke YHWH.

Ahab is condemned for this same sin—וַיַּעַשׂ אַחְאָב אֶת הָאֲשֵׁרָה “Ahab made an asherah” (1 Kgs 16:33)—a practice that the book repeatedly condemns along with high places and standing stones (most clearly in 1 Kgs 14:23; 2 Kgs 17:10). It would thus be unthinkable for a Deuteronomic text to include an etiology in favor of an asherah, and in the Jerusalem Temple no less. The story of the flowering staff, however, is not Deuteronomic but is part of the Priestly Text.

No Priestly Objection to Asherim

Unlike Deuteronomy, the priestly literature—both P and H—expresses no hostility to asherim. Priestly literature has its own conception of what constitutes heterodox worship and condemns it. For example, it prohibits the use of idols and cast metal gods (Lev 19:4), and of idols (again), sculptures, standing stones, and stone reliefs (Lev 26:1). It condemns high places and “incense stands” (חַמָּנִים) (Lev 26:30). And it mandates the destruction of the Canaanites’ reliefs, cast metal images, and high places (Num 33:52). Nevertheless, it never mentions asherim.

Ezekiel the Priestly Prophet

This lack of hostility toward asherim is apparent in the book of Ezekiel as well, a work which has well-known ties to the priestly literature of the Torah. Like the Priestly texts, although Ezekiel condemns high places, altars, and incense stands (Ezek 6:3–6), he says nothing about asherim.

In this regard, the book of Ezekiel contrasts with other prophetic books: Isaiah condemns asherim along with altars and incense stands (Isa 17:8; 27:9); Micah condemns them along with sculptures and standing stones (Mic 5:12–13); and Jeremiah condemns them along with altars and high places (Jer 17:2–3).

The Deuteronomic and Deuteronomistic authors, and, presumably the authors of the cited passages in Isaiah, Micah, and Jeremiah, viewed the asherah as illegitimate. Unlike them, the priestly author(s), and presumably Ezekiel, thought that the asherah could serve as a legitimate symbol of the Aaronide priesthood.

Sources of Blessing

The asherim and the Aaronide priesthood both have similar functions: they are sources of YHWH’s blessing. Priests, in addition to offering sacrifices, bless the people:

במדבר ו:כב וַיְדַבֵּר יְ־הוָה אֶל מֹשֶׁה לֵּאמֹר.ו:כג דַּבֵּר אֶל אַהֲרֹן וְאֶל בָּנָיו לֵאמֹר כֹּה תְבָרְכוּ אֶת בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל אָמוֹר לָהֶם. ו:כדיְבָרֶכְךָ יְ־הוָה וְיִשְׁמְרֶךָ. ו:כה יָאֵר יְ־הוָה פָּנָיו אֵלֶיךָ וִיחֻנֶּךָּ. ו:כו יִשָּׂא יְ־הוָה פָּנָיו אֵלֶיךָ וְיָשֵׂם לְךָ שָׁלוֹם. ו:כז וְשָׂמוּ אֶת שְׁמִי עַל בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל וַאֲנִי אֲבָרֲכֵם.

Num 6:22 YHWH spoke to Moses: 6:23 Speak to Aaron and his sons: Thus shall you bless the people of Israel. Say to them: 6:24 YHWH bless you and protect you! 6:25 YHWH deal kindly and graciously with you! 6:26 YHWH bestow His favor upon you and grant you peace! 6:27 Thus they shall link My name with the people of Israel, and I will bless them.

The notion that the priests were chosen to bless in Yhwh’s name is endorsed in a number of other places in biblical literature (Deut 10:8; 21:5; 1 Chr 23:13; and Sir 45:15; see also Gen 14:18–19; 2 Chr 30:27). In fact, kohanim (held to be the descendants of Aaronide priests) continue this practice, using the cited formula, to the present day.

Various pieces of evidence suggest that asherim were thought to facilitate the grant of Yhwh’s blessing as well.

Inscriptions—All three clear occurrences of the word asherah in inscriptions are situated within blessing formulae:

- Khirbet el-Qom inscription 1 reads,

ברכ אריהו ליהוה <ו>לאשרתה

Blessed is Uriahu by Yhwh <and> his asherah.[22]

- Kuntillet ‘Ajrud inscription 3.1 reads,

ברכת. אתכמ. ליהוה. שמרנ. ולאשרתה

I bless you [pl.] by Yhwh of Samaria and his asherah.[23]

- And Kuntillet ‘Ajrud inscription 3.6 reads,

ברכתכ. ליהוה תמנ ולאשרתה. יברכ וישמרכ

I bless you by Yhwh of Teman and his asherah; may he bless you and watch over you.[24]

The formula in the last example is identical to the formula referenced in Numbers as the proper Aaronide blessing.[25]

The Hebrew Root—One of the essential meanings of the root א.שׁ.ר overlaps to a great degree with that of ב.ר.ך, “bless.” This seems to be the meaning of the name given the eponymous ancestor of the tribe Asher by his mother:

בראשית ל:יג וַתֹּאמֶר לֵאָה בְּאָשְׁרִי כִּי אִשְּׁרוּנִי בָּנוֹת וַתִּקְרָא אֶת שְׁמוֹ אָשֵׁר.

Gen 30:13 Leah declared, “What fortune (oshri)! For women will deem me fortunate/blessed (ishruni).” So she named him Asher.

In fact, the blessing of Moses (Deut 33:24), in an apparent play on the tribe’s name, reads, “blessed among children is Asher” (בָּרוּךְ מִבָּנִים אָשֵׁר).

In addition, the terms א.שׁ.ר and ב.ר.כ are used in poetic parallelism. For example, Psalm 72, the finale of “the prayers of David son of Jesse” (v. 20), reads,

תהלים עב:יז וְיִתְבָּרְכוּ בוֹ כָּל גּוֹיִם יְאַשְּׁרוּהוּ

Ps 72:17 May [people] bless themselves (ב.ר.כ) by him; may all nations call him blessed (א.שׁ.ר)”

A subtler but perhaps stronger connection between these terms can be seen in the parallel between Jeremiah 17:7, which reads, “blessed is the man” (בָּרוּךְ הַגֶּבֶר) and Psalm 1:1, which reads, “fortunate is the man” (אַשְֽׁרֵי הָאִישׁ). In both cases, this declaration is followed by an extended simile of a flourishing tree, implying that both poets were using a stock image: blessing is like a tree.[26]

These similes remind us of an additional connection between asherim and blessing: the stylized tree motif, with which the asherah has been independently identified, immediately evokes the notion of blessing. Its typical blossoms and curlicues suggest flourishing, and the caprids often shown feeding from it, as in the aforementioned specimen from Kuntillet ‘Ajrud, suggest sustenance and bounty.[27]

Placement Near Altars—The assumption that asherim were thought to facilitate blessing accounts for their portrayal in the Tanakh as objects conventionally placed by altars (most clearly in Deut 16:21; Judg 6:25–30; 2 Kgs 23:15). One of the purposes of altar compounds was to attract the blessing of Yhwh, as we read in the Covenant Collection,

שמות כ:כד בְּכָל הַמָּקוֹם אֲשֶׁר אַזְכִּיר אֶת שְׁמִי אָבוֹא אֵלֶיךָ וּבֵרַכְתִּיךָ.

Exod 20:24 Anywhere I have my name mentioned, I will come to you and bless you.

Given that “standing stones” (מַצֵּבוֹת) may have been thought to house deities,[28] one might even suggest that the logic behind the common pairing of asherim with standing stones at altars is that the standing stones ensure the fulfillment of “I will come to you” while the asherim ensure the fulfillment of “… and bless you.”

In Defense of the Priestly Asherah

The Priestly account of Aaron’s flowering staff interprets the asherah in the temple of Yhwh as the age-old staff of Aaron put there at Yhwh’s command in order to serve as a warning against usurpation of the Aaronic office. By means of this interpretation, the account at once gave qualified approval for the asherah and appropriated its popularly conceived function, namely facilitating the grant of Yhwh’s blessing, to the Aaronides.

In this sense, the story is a counterpart of the non-priestly account of the bronze snake (Num 21:4–9), which is an etiology for the copper serpent Nehushtan destroyed by Hezekiah (2 Kgs 18:4), and which attributes that object’s powers of revival to the will of Yhwh as carried out through the exclusive authority of Moses.[29]

This also gives us a terminus ad quem for when the story of Aaron’s flowering staff must have been composed, namely, before (or around) the time of Josiah’s purge,[30] as it is implausible that anyone would compose and successfully propagate a subversive etiology of an object that was not in contemporary use.[31]

If this conclusion is correct, it shows that there was disagreement among the biblical authors about the very legitimacy of what was likely the central cultic object for many Israelites, and it illustrates a method by which a biblical author could give qualified approval to an object condemned by his peers.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

July 3, 2019

|

Last Updated

February 2, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Raanan Eichler is an Associate Professor of Bible at Bar-Ilan University in Israel. He received his Ph.D. from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and completed fellowships at Harvard University and Tel Aviv University. He is the author of The Ark and the Cherubim (Mohr Siebeck, 2021) and many academic articles.

Essays on Related Topics: