Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Anchored in the Authority of Sinai

Moses on Mount Sinai, Jean-Léon Gérôme, 1895

Israel’s foundational encounter with YHWH at Mount Sinai/Horeb was revised and reimagined over and over again. The earliest preserved accounts are in the Torah itself, which contains:[1]

- A non-Priestly theophany at Horeb that includes the Covenant Collection.

- Deuteronomy’s combined Horeb and Moab covenant that features the Decalogue.

- The Priestly account at Sinai making the Tabernacle the locus of revelation.

Additional accounts were composed after the Torah had been compiled:

- The book of Jubilees recounts supplementary revelations that were given to Moses during his first 40 days on Sinai.

- The Temple Scroll imagines that instructions for the future temple were delivered to Moses during his second 40 days on Sinai.

- The Samaritan Pentateuch incorporates the sanctuary at Mt. Gerizim into the Decalogue.

- The rabbis claim that the Oral Torah was revealed to Moses at Sinai, alongside the written Torah.

These accounts all use the authority of the divine revelation at Horeb/Sinai to sanction their own views, ideas, and practices. Here’s how they did it.

The Horeb Revelation in Exodus

The non-Priestly version of the account has the Israelites leave Egypt and encamp at the mountain of God, Horeb (Exod 3:1, 18:5). YHWH then appears and speaks to Moses as the Israelites look on:

שׁמות כ:יח וְכָל הָעָם רֹאִים אֶת הַקּוֹלֹת וְאֶת הַלַּפִּידִם וְאֵת קוֹל הַשֹּׁפָר וְאֶת הָהָר עָשֵׁן וַיַּרְא הָעָם וַיָּנֻעוּ וַיַּעַמְדוּ מֵרָחֹק. כ:יט וַיֹּאמְרוּ אֶל מֹשֶׁה דַּבֵּר אַתָּה עִמָּנוּ וְנִשְׁמָעָה וְאַל יְדַבֵּר עִמָּנוּ אֱלֹהִים פֶּן נָמוּת.

Exod 20:18 [*20:15] When all the people witnessed the thunder and lightning, the sound of the trumpet, and the mountain smoking, they were afraid and trembled and stood at a distance. 20:19 [*20:16] and said to Moses, “You speak to us, and we will listen, but do not let God speak to us, lest we die.”[2]

In this initial encounter, God speaks the Decalogue (20:2–17 [*20:2–14]), although this divine speech might have been added to an account that originally described a divine appearance without speech.[3] The episode serves to establish Moses’s legitimacy as an intermediary and to convince the Israelites that they are not entitled to, and do not want, direct communication from YHWH, necessitating the institution of prophecy.[4] In this account, the Decalogue is neither written down nor accepted by the Israelites as binding law.[5] Instead, God’s appearance and speech set the stage for the private revelation of the Covenant Collection (20:24–23:19 [*20:21–23:19]) to Moses.

The Covenant Collection forms the legal basis for the Horeb covenant, affirmed in multiple steps, each of which escalates the authority and permanence of the covenant: an oral agreement (24:3), the writing of a scroll (v. 4a), a sacrificial covenant ceremony (vv. 4b–8), and finally God’s inscription of the laws that constitute this collection on stone tablets (v. 12).

Deuteronomy Re-imagines Horeb

Deuteronomy knows some form of this account, and reimagines the encounter with God at Horeb, presenting the Decalogue, not the Covenant Collection, as the basis of the Horeb covenant and as the document written by God on the stone tablets:

דברים ד:יג וַיַּגֵּד לָכֶם אֶת בְּרִיתוֹ אֲשֶׁר צִוָּה אֶתְכֶם לַעֲשׂוֹת עֲשֶׂרֶת הַדְּבָרִים וַיִּכְתְּבֵם עַל שְׁנֵי לֻחוֹת אֲבָנִים.

Deut 4:13 He declared to you his covenant, which he charged you to observe, that is, the ten commandments, and he wrote them on two stone tablets.

In this version of events, the Israelites do not assent to the main body of law at Horeb. This happens much later, only after Moses has “expounded” on the law throughout Deuteronomy:[6]

דברים כח:סט אֵלֶּה דִבְרֵי הַבְּרִית אֲשֶׁר צִוָּה יְ־הוָה אֶת מֹשֶׁה לִכְרֹת אֶת בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל בְּאֶרֶץ מוֹאָב מִלְּבַד הַבְּרִית אֲשֶׁר כָּרַת אִתָּם בְּחֹרֵב.

Deut 29:1 [*28:69] These are the words of the covenant that YHWH commanded Moses to make with the Israelites in the land of Moab, in addition to the covenant that he had made with them at Horeb.

As a result of these changes, the Israelites are bound not by the Covenant Collection recorded in Exodus, but by the reworking of those laws presented in Deuteronomy.[7]

The Priestly Sinai Account: Bringing the Revelation of Law to the Tabernacle

In the Priestly account of Israel’s encounter with YHWH, the divine mountain is called by the more familiar name of Sinai, but its importance is drastically reduced.[8] As in the Horeb account, Moses ascends the mountain (Exod 24:16–18). In this version, however, after commanding Moses to collect a donation of materials from the Israelites (25:1–7), YHWH does not offer a general set of laws, but only provides instructions for how to build the Tabernacle (chs. 25–27):

שׁמות כה:ח וְעָשׂוּ לִי מִקְדָּשׁ וְשָׁכַנְתִּי בְּתוֹכָם. כה:ט כְּכֹל אֲשֶׁר אֲנִי מַרְאֶה אוֹתְךָ אֵת תַּבְנִית הַמִּשְׁכָּן וְאֵת תַּבְנִית כָּל כֵּלָיו וְכֵן תַּעֲשׂוּ.

Exod 25:8 And they shall make me a sanctuary so that I may dwell among them. 25:9 In accordance with all that I show you concerning the pattern of the Tabernacle and of all its furniture, so you shall make it.

The completed Tabernacle will soon eclipse Sinai as the true locus of revelation:

שׁמות כה:כב וְנוֹעַדְתִּי לְךָ שָׁם וְדִבַּרְתִּי אִתְּךָ מֵעַל הַכַּפֹּרֶת מִבֵּין שְׁנֵי הַכְּרֻבִים אֲשֶׁר עַל אֲרֹן הָעֵדֻת אֵת כָּל אֲשֶׁר אֲצַוֶּה אוֹתְךָ אֶל בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל.

Exod 25:22 There I will meet with you, and from above the cover, from between the two cherubim that are on the ark of the covenant, I will tell you all that I am commanding you for the Israelites.

This statement, with the qualifier כָּל, “all,” sits uneasily in the composite text of Exodus, in which YHWH has already transmitted the Decalogue and the Covenant Collection. Isolated from the non-Priestly material, the Priestly account in effect denies that any law was given or covenant made on the mountain, rejecting the central claim of the two Horeb accounts found in Exodus and Deuteronomy. At the same time, however, the Priestly account uses the divine revelation of the Tabernacle on the mountain to sanction all of the laws that YHWH will subsequently reveal (in the following book of Leviticus) to the Israelites in the Tabernacle.

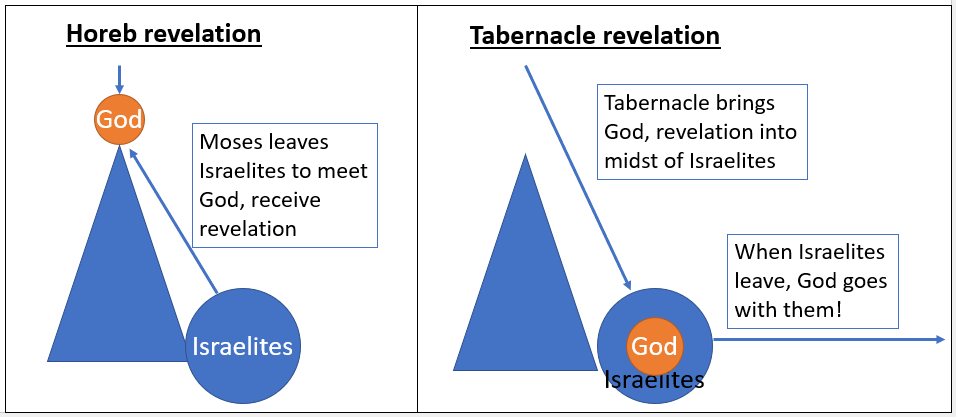

A major goal of the Priestly story is to make it possible for YHWH to dwell in the midst of his people (Exod 29:45). The non-Priestly mountain revelation requires Moses to leave the people and come to YHWH, but in the Priestly source, the Tabernacle is built in the midst of the Israelite camp, at the base of Sinai rather than its summit, so that YHWH may come to the Israelites (ch. 40).[9] Moreover, in the Priestly account, when the Israelites leave the mountain (Num 10:12), God can go with them and revelation can continue (Num 15; 18–19; 27–30; 35–36).

Jubilees: Sinai as Ancestral and Cosmic Reality

The book of Jubilees (2nd century B.C.E.) describes in detail a revelation to Moses during his first forty-day sojourn on Mount Sinai (Exod 24:18). Quoting extensively from Exodus 24, the first chapter begins with YHWH calling Moses to ascend the mountain:

Jub 1:1 During the first year of the Israelites’ exodus from Egypt, in the third month—on the sixteenth of this month—the Lord said to Moses: “Come up to me to the mountain. I will give you the two stone tablets, the law and the commandment that I have written so that you may teach them.”[10]

YHWH then instructs Moses to write down in a book (i.e., the book of Jubilees) the entirety of the revelation that he will receive:

Jub 1:5 He said to him: “Pay attention to all the words that I tell you on this mountain. Write them in a book so that their generations may know that I have not abandoned them because of all the evil they have done in breaking[11] the covenant between me and you that I am making today on Mount Sinai for their offspring.

After speaking with Moses, YHWH dispatches an “Angel of the Presence” to dictate a lengthy revelation to Moses (1:27). In the chapters that follow, this angel reveals to Moses that the Sinai laws are not arbitrary or parochial. Instead, they are a codification of ancestral, primeval, and even cosmic reality.[12]

For example, in the Torah, circumcision is “legislated” when YHWH makes a covenant with Abraham and his descendants (Gen 17). In Jubilees, the angel of the presence recounts the Abraham narrative and declares that the law of circumcision is an eternal requirement (15:1–26). He then justifies the law by claiming that circumcision makes the Israelites like the highest orders of angels:[13]

Jub 15:27 For this is what the nature of all the angels of the presence and all the angels of holiness was like from the day of their creation. In front of the angels of the presence and the angels of holiness he sanctified Israel to be with him and his holy angels.

This equation of Israelite practice and angelic reality emphasizes Israel’s chosenness, pushes the precedent for circumcision from the time of Abraham back to the dawn of creation, and likely reflects the increasing importance of circumcision in the (largely uncircumcised) Greco-Roman world in which Jubilees was written.[14] After elevating circumcision in this way, the angel instructs Moses to provide the Israelites with detailed circumcision regulations:

Jub 15:28 Now you command the Israelites to keep the sign of this covenant throughout their history as an eternal ordinance so that they may not be uprooted from the earth 15:29 because the command has been ordained as a covenant so that they should keep it forever on all the Israelites.[15]

Jubilees thus effectively adds these regulations to the Sinai revelation and Mosaic law. This contrasts sharply with the Torah, which narrates the law of circumcision to Abraham (Gen 17), but does not repeat it in detail in relation to the Sinai revelation.[16]

The Temple Scroll: Everything Happened at Sinai

The Temple Scroll (2nd century B.C.E.) contains a rewritten Torah that rearranges Deuteronomic, Priestly, and other laws found throughout the Torah, harmonizing and updating them in the process. For example, its extensive festival calendar (cols. 13–30) combines material from, among other places, the calendars in Leviticus 23 and Deuteronomy 16 and the ritual regulations in Numbers 28–29. It also adds first fruits festivals for wine (19:11–21:10) and oil (21:12–23:2) that are modeled after Shavuot.[17]

The introduction to the Temple Scroll is missing, but the surviving fragments from the second column are based closely on the covenant renewal in Exodus 34, suggesting that the Temple Scroll has co-opted the setting of that chapter: Moses’s second forty-day stint on Sinai.[18] The authors thereby relocate the revelation of the laws of Leviticus and Numbers from the Tabernacle to the mountain and provide Deuteronomy’s Mosaic laws with a divine precedent at Sinai/Horeb that Deuteronomy claims for them but that has little basis in Exodus.[19]

The Temple Scroll also recasts Tabernacle instructions as temple instructions, beginning with a command to build a temple (cols. 3–13; 30–47). For example, while Exodus presents a call for donations of materials for the Tabernacle (25:3–9, 35:5–9), the Temple Scroll directs its donations to the temple:[20]

6 [ ]...כי אם מן ה֯[תרומה תקח

11Q19 3:6 Rather, from the [donation(s) take:]

7 [זהב וכסף ונחו]ש̇ת וברזל ואבני גזית לב֯[ית ולכול אשר]

3:7 [gold, silver, bro]nze, iron, and dressed stones for the h[ouse and for everything that is]

8 [בבית ]ו{י}את כול כליו יעשו זהב טהו[ר...]

3:8 [in the house …] And all its vessels shall be made from pu[re] gold[…].[21]

The temple instructions thus fill a gap in the Torah, which contains no command to build a Temple, nor instructions for constructing or using it, and they turn a story about what had been done in the ancient wilderness into a divine demand, revealed at Sinai, for what should be done here and now.[22]

The Samaritan Pentateuch: God Chose Gerizim at Sinai

The Samaritan Pentateuch anchors its central cult site in the Sinai encounter.[23] At the end of its Decalogue, before the people respond with fear and refuse to receive further direct revelation (Exod 20:17), the Samaritan Pentateuch includes an additional law, called the “Gerizim Commandment,” which requires the people to construct an altar on Mount Gerizim, the location of the later Samaritan sanctuary:

והיה כי יביאך י־הוה אלהיך אל ארץ הכנעני אשר אתה בא שמה לרשתה והקמת לך אבנים גדלות ושדת אתם בשיד וכתבת על האבנים את כל דברי התורה הזאת. והיה בעברכם את הירדן תקימו את האבנים האלה אשר אנכי מצוה אתכם היום בהר גריזים ובנית שם מזבח לי־הוה אלהיך מזבח אבנים. לא תניף עליהם ברזל, אבנים שלמות תבנה את מזבח י־הוה אלהיך.

When YHWH your God has brought you into the land of the Canaanites, which you are entering to occupy, you shall set up large stones and cover them with plaster. You shall write on the stones all the words of this law. So when you have crossed over the Jordan, you shall set up these stones, about which I am commanding you today, on Mount Gerizim, you shall build an altar there to YHWH your God, an altar of stones on which you have not used an iron tool. You must build the altar of YHWH your God of unhewn stones.[24]

By inserting this commandment into the only occasion in which God reveals law directly to the Israelites at Sinai, the Samaritan Pentateuch claims for worship at Gerizim an authority and authenticity even greater than that of the laws mediated through Moses.[25]

The Vitality of Tradition in Ancient Judaism

The rabbis similarly added their voices to the Sinai traditions, asserting that all of Oral Torah was revealed to Moses on the mountain.

בבלי ברכות ה. ואמר רבי לוי בר חמא אמר רבי שמעון בן לקיש: מאי דכתיב ואתנה לך את לחת האבן והתורה והמצוה אשר כתבתי להורותם, לחות – אלו עשרת הדברות, תורה – זה מקרא, והמצוה – זו משנה, אשר כתבתי – אלו נביאים וכתובים, להורותם – זה תלמוד; מלמד שכולם נתנו למשה מסיני.

b. Ber. 5a R. Levi bar Chama said further in the name of R. Simeon ben Lakish: “What is the meaning of the verse (Exod 24:12): ‘And the LORD said to Moses, Come up to me into the mount, and be there: and I will give you the tablets of stone, the law and the commandment which I have written to teach them’? ‘Tablets of stone’ — the Decalogue; ‘the law’ — Scripture; ‘the commandment’ — Mishnah; ‘which I have written’ — the Prophets and Hagiographa; ‘to teach them’ — Gemara. This teaches that all these were given to Moses from Sinai.”[26]

Like their predecessors, the rabbis reimagined Israel’s foundational encounter with its God at Mount Sinai/Horeb in ways that gave that story new vitality, while anchoring their ideas in the authority of divine revelation.

A series of processes—a combination of intentional literary decisions and historical accidents—has obscured the diversity of the Sinai/Horeb narratives that existed among the ancient sources. First, several distinct accounts of Israel’s origins were combined into a single composite account: the Torah. Second, later retellings of the Torah, such as those in Jubilees and the Temple Scroll, were marginalized or eliminated. Third, the diverse versions and copies of the Torah that circulated in the late Second Temple period were reduced, as Jewish communities (at least those who survived the brutal Roman suppressions of the Jewish revolts in the first and second centuries C.E.) settled on a more fixed text tradition that would become the Masoretic Text.[27]

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

February 5, 2023

|

Last Updated

March 17, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Kevin Mattison is is Lecturer of Jewish Studies at the University of Bristol. He holds a Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin–Madison and an M.A. from Brandeis University and is the author of Rewriting and Revision as Amendment in the Laws of Deuteronomy (Mohr Siebeck, 2018). His current book project, Transforming the Torah: Reimagining Israel’s Origins in Ancient Judaism, examines the variety of retellings of the Torah that proliferated in the Second Temple period.

Essays on Related Topics: