Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Ataroth and the Inscribed Altar: Who Won the War Between Moab and Israel?

Chris Rollston examining the Khirbat Ataruz altar inscription. Photo Courtesy of C. Rollston

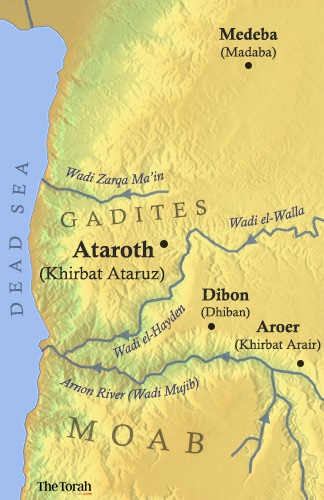

The Transjordanian city of Ataroth (עֲטָרוֹת, ʿăṭārôt) appears only twice in the Torah and nowhere else in the Bible.[1] It would have remained little more than an obscure biblical toponym (place name) were it not for two modern archaeological discoveries that have made it a showcase example of the connection of biblical narrative to archaeological and epigraphic data.[2]

Ataroth in the Torah

Both references to the city in the Torah appear in Numbers 32, as part of the territory that the tribes of Gad and Reuben settle. Its first appearance is among the cities Gad and Reuben list, when they ask Moses for permission to settle in the region, due to its suitability for raising cattle:

במדבר לב:ב וַיָּבֹאוּ בְנֵי גָד וּבְנֵי רְאוּבֵן וַיֹּאמְרוּ אֶל מֹשֶׁה וְאֶל אֶלְעָזָר הַכֹּהֵן וְאֶל נְשִׂיאֵי הָעֵדָה לֵאמֹר. לב:ג עֲטָרוֹת וְדִיבֹן וְיַעְזֵר וְנִמְרָה וְחֶשְׁבּוֹן וְאֶלְעָלֵה וּשְׂבָם וּנְבוֹ וּבְעֹן. לב:ד הָאָרֶץ אֲשֶׁר הִכָּה יְ־הוָה לִפְנֵי עֲדַת יִשְׂרָאֵל אֶרֶץ מִקְנֶה הִוא וְלַעֲבָדֶיךָ מִקְנֶה.

Num 32:2 The Gadites and the Reubenites came to Moses, Eleazar the priest, and the chieftains of the community, and said, 32:3 “Ataroth, Dibon, Jazer, Nimrah, Heshbon, Elealeh, Sebam, Nebo, and Beon—32:4 the land that YHWH has conquered for the community of Israel is cattle country, and your servants have cattle…”

The Gadites and Reubenites request this area as their lot, and after some back and forth, Moses grants the request on the condition that the men of Gad and Reuben first participate in the conquest of Canaan with the other tribes.

במדבר לב:לד וַיִּבְנוּ בְנֵי גָד אֶת דִּיבֹן וְאֶת עֲטָרֹת וְאֵת עֲרֹעֵר. לב:לה וְאֶת עַטְרֹת שׁוֹפָן וְאֶת יַעְזֵר וְיָגְבֳּהָה. לב:לו וְאֶת בֵּית נִמְרָה וְאֶת בֵּית הָרָן עָרֵי מִבְצָר וְגִדְרֹת צֹאן. לב:לז וּבְנֵי רְאוּבֵן בָּנוּ...

Num 32:34 The Gadites built Dibon, Ataroth, Aroer, 32:35 Atroth-shophan, Jazer, Jogbehah, 32:36 Beth-nimrah, and Beth-haran as fortified towns or as enclosures for flocks. 32:37 The Reubenites built…

Nothing about this city stands out in these verses in comparison to the other cities. This changed, however, with the discovery of the Mesha Stele, a monumental inscription of the Moabite king Mesha from the 9th century B.C.E. at Dhiban, Jordan.[3]

Ataroth in the Mesha Inscription

First brought to the attention of interested European travelers by local residents in 1868, the Mesha Stele, written in the Moabite language, which is very similar to biblical Hebrew, presents itself as a first-person account from the same King Mesha named in 2 Kgs 3:4, opening with אנכ. משע.... מלך. מאב, “I, Mesha…, king of Moab.” In the Mesha Inscription, Mesha declares how the Moabite god Kemosh had punitively allowed Moab to be subjected to the hegemony of King Omri of Israel, but that in the reign of Omri’s “son,”[4] Mesha rebelled and reconquered much of the historic Moabite territory.

Mesha also boasts of his public works, including building activities at many locations within Moab that he acknowledges were previously built up by the Israelite King Omri. Among all these fascinating details, of most importance for this discussion are the events narrated in lines 10–14:

ואש. גד. ישב. בארצ. עטרת. מעלמ. ויבנ. לה. מלכ. ישראל. את. עטרת |

Now the people of Gad had dwelt in the region of Ataroth (ʿṭrt) for a long time, and the king of Israel built Ataroth for them.

ואלתחמ. בקר. ואחזה | ואהרג. את. כל. העם. הקר. רית. לכמש. ולמאב |

But I fought against the city and I took it, and I killed all the people, and the city was a satiation[5] for Kemosh and for Moab.

ואשב. משמ. את. אראל. דודה. ואס חבה. לפני. כמש. בקרית |

And I took from there its ʾrʾldwd[6] and I brought it before Kemosh in Qiryat.

ואשב. בה. את. אש. שרן. ואת. אש. מחרת |

And I settled the Sharonites and the Maḥarites in it.

To be sure, this epigraphic witness does not relate directly to the events described in Numbers 32, nor does it say anything about their specific correlation with historical reality, but it does put Ataroth “on the map” by the 9th century B.C.E. and confirms its association with a people group named Gad and the Northern Kingdom of Israel.[7]

The Excavations at Khirbat Ataruz

Further light on this city has been shed by studying the ruin of Khirbat Ataruz, located 24 km southwest of Madaba in Jordan. The site has long been identified as the location of ancient Ataroth, based on both its geographical location and the approximate preservation of its ancient name in the modern Arabic place name. In 2000, Prof. Chang-Ho Ji of La Sierra University began excavation of the site, uncovering remarkable finds, including cultic architecture of multiple phases and many religious artifacts.[8]

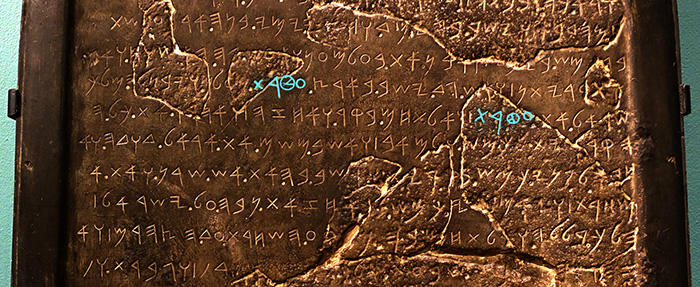

The Ataruz Inscribed Altar

During the 2010 excavation season, a cylindrical stone altar bearing seven lines of inscribed text was discovered in a small sanctuary room.[9] The language of this inscription is Moabite, and its script can be dated paleographically to the late 9th or early 8th centuries B.C.E.

The inscription provides important new details about the Moabite language, supplying a number of words and grammatical features attested in Moabite for the first time. Additionally, in contrast to the earlier script of the Mesha Inscription, which is identical to contemporary Hebrew script, the Ataruz Inscribed altar shows an “Early Moabite Script” diverging from the Hebrew script, and is now possibly the earliest extant inscription employing this script.

To explain, while the Mesha Stele (hailing from, as noted above, a generation or two earlier than the Ataruz inscriptions) is written in the Moabite language, it uses the Old Hebrew script, not a distinctive Moabite national script.[10] One could thus contend that after the hegemony of the Omrides of Israel concluded, a fledgling, distinctive Moabite national script soon developed.[11]

This distinctive Moabite script and language are also attested in later inscriptions such as the Mudeyineh Incense Altar Inscription.[12] Based on its stratigraphic location and this script, the Ataruz Inscribed Altar is dated to the decades following the Moabite conquest described in the Mesha Stele.

The inscribed altar bears seven lines of text, representing two separate inscriptions: one (A) of three lines, and a second (B) of four lines, at perpendicular orientation to the other. Its contents have been difficult to decipher, as it uses hieratic numerals (a numbering system originating in Egypt), abbreviations, and some idiosyncratic letter forms, but some tentative conclusions have been reached in our publication of the inscription.[13]

Inscription A records a sum of 10 shekels of bronze, using hieratic numerals for the quantities, the abbreviation שׁל (šl) for shekels, and the abbreviation נ (n) for נחשׁת (nḥšt), “bronze.” The word בז (bz), “plunder,” may occur, possibly indicating that the recorded bronze was plundered at the conquered site and, based on the context of the inscription, dedicated in the shrine where the altar was found.

Inscription B consists of four difficult lines of text which appear to refer to:

- קר הצדת (qr hṣdt), “the desolated city”—This phrase uses the distinctive Moabite word for city קר (qr), also used in reference to Ataroth in the Mesha Inscription.[14] The description of the city as “desolated” uses language very similar to Zeph 3:6.

- גרנ פשׁנ (grn pšn) “scattered foreigners”—This phrase includes the noun gr that is also found in the Mesha Inscription and is cognate to biblical Hebrew גֵר (gēr).

- עברנ (ʿbrn) “Hebrews” (with the Moabite plural ending nun)—The reading of these letters is clear, but “Hebrews” is only one of multiple possible interpretations. This would arguably be the earliest extant epigraphic occurrence of this word if so interpreted.[15]

The cluster of these possible readings suggests that the inscription may be commemorative/dedicatory in nature and might actually evoke events related to the Moabite conquest of the city. As such, this finding contributes to an issue scholars have discussed ever since the Mesha Inscription was found, namely the tension between Mesha’s story and the biblical account of this war in 2 Kings 3.

“The King of Moab Rebelled against Israel”—2 Kings 3:5

When the Mesha Inscription was first discovered, scholars immediately noted how it provides a remarkable contemporary witness to the conflict between Moab and the Northern Kingdom of Israel under the Omride Dynasty as described in Kings. In fact, on one level, it correlates remarkably with the biblical account, which mentions the rebellion of Moab against the Omrides and names Mesha specifically:

מלכים ב ג:ד וּמֵישַׁע מֶלֶךְ מוֹאָב הָיָה נֹקֵד וְהֵשִׁיב לְמֶלֶךְ יִשְׂרָאֵל מֵאָה אֶלֶף כָּרִים וּמֵאָה אֶלֶף אֵילִים צָמֶר. ג:ה וַיְהִי כְּמוֹת אַחְאָב וַיִּפְשַׁע מֶלֶךְ מוֹאָב בְּמֶלֶךְ יִשְׂרָאֵל.

2 Kgs 3:4 Now King Mesha of Moab was a sheep breeder; and he used to pay as tribute to the king of Israel a hundred thousand lambs and the wool of a hundred thousand rams. 3:5 But when Ahab died, the king of Moab rebelled against the king of Israel.

The story continues with the Israelite response to this rebellion, in which King Jehoram of Israel, King Jehoshaphat of Judah, and the (unnamed) king of Edom march together against Moab. In 2 Kings 3:24–25, that conflict is presented as an initial rout of Moab,

מלכים ב ג:כד …וַיָּקֻמוּ יִשְׂרָאֵל וַיַּכּוּ אֶת מוֹאָב וַיָּנֻסוּ מִפְּנֵיהֶם (ויבו) [וַיַּכּוּ] בָהּ וְהַכּוֹת אֶת מוֹאָב. ג:כה וְהֶעָרִים יַהֲרֹסוּ וְכָל חֶלְקָה טוֹבָה יַשְׁלִיכוּ אִישׁ אַבְנוֹ וּמִלְאוּהָ וְכָל מַעְיַן מַיִם יִסְתֹּמוּ וְכָל עֵץ טוֹב יַפִּילוּ עַד הִשְׁאִיר אֲבָנֶיהָ בַּקִּיר חֲרָשֶׂת וַיָּסֹבּוּ הַקַּלָּעִים וַיַּכּוּהָ.

2 Kgs 3:24 …And the Israelites arose and attacked the Moabites, who fled before them. They advanced, constantly attacking the Moabites, 3:25 and they destroyed the towns. Every man threw a stone into each fertile field, so that it was covered over; and they stopped up every spring and felled every fruit tree. Only the walls of Kir-hareseth were left, and then the slingers surrounded it and attacked it.

Israel’s rapid advance against Moab having come to a halt at Moab’s capital at Kir-hareseth (usually identified as the city of Karak, Jordan), the story ends with a surprising twist:

מלכים ב ג:כו וַיַּרְא מֶלֶךְ מוֹאָב כִּי חָזַק מִמֶּנּוּ הַמִּלְחָמָה וַיִּקַּח אוֹתוֹ שְׁבַע מֵאוֹת אִישׁ שֹׁלֵף חֶרֶב לְהַבְקִיעַ אֶל מֶלֶךְ אֱדוֹם וְלֹא יָכֹלוּ. ג:כז וַיִּקַּח אֶת בְּנוֹ הַבְּכוֹר אֲשֶׁר יִמְלֹךְ תַּחְתָּיו וַיַּעֲלֵהוּ עֹלָה עַל הַחֹמָה וַיְהִי קֶצֶף גָּדוֹל עַל יִשְׂרָאֵל וַיִּסְעוּ מֵעָלָיו וַיָּשֻׁבוּ לָאָרֶץ.

2 Kgs 3:26 Seeing that the battle was going against him, the king of Moab led an attempt of seven hundred swordsmen to break a way through to the king of Edom; but they failed. 3:27 So he took his first-born son, who was to succeed him as king, and offered him up on the wall as a burnt offering. A great wrath came upon Israel, so they withdrew from him and went back to [their own] land.

Whatever the phrase “great wrath” means,[16] Mesha’s sacrifice of his own son works;[17] the Israelite coalition gives up on its attempt to conquer Moab and returns home.

On one hand, this story does not contradict Mesha’s description exactly. The Bible admits that the attempt to take Moab’s capital fails, and says nothing about whether Israel maintains control over the rest of Moab or not. And yet, the accounts are quite different from each other in tone and implication.

The Bible describes how the coalition of Israelite, Judahite, and Edomite armies destroyed all other cities except the Moabite capital, implying that Moab was greatly weakened though not destroyed. Mesha’s account, however, makes no mention of an Israelite incursion and, more importantly, presents this rebellion as a decisive and enduring victory in which Mesha retakes the area north of the Arnon River all the way to Nebo from Israel. It further describes how he resettled those areas and commenced various royal building projects, implying that Israel was no longer a factor at all, and that Mesha’s victory was decisive and long-lasting.

While it is likely that the narrative has been given some “spin” on both sides, the evidence from Khirbat Ataruz lends further support to the validity of Mesha’s claim to have conquered, held, and resettled the city of Ataroth. First, the very existence of a Moabite Temple with an inscription on an altar in the Moabite language and in the Moabite script, the Ataruz Inscribed Altar, corroborates Mesha’s statement that he conquered the city of Ataroth and resettled it.

Furthermore, if the reading of Inscription B suggested above is correct, then it may be another inscription celebrating this victory at the site of one of the newly conquered Moabite towns. Notably, this conquest of Israelite territory by the Moabites is something the biblical picture of Mesha’s rebellion conceals in its version of the story. However, with the modern disciplines of archaeology and epigraphy, evidence of the scope of this Moabite conquest is slowly coming to light.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

July 13, 2020

|

Last Updated

March 14, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Adam L. Bean is Visiting Assistant Professor of Biblical Studies at Milligan University and holds a Ph.D and M.A. in Near Eastern Studies from the Johns Hopkins University. He is co-author with Christopher A. Rollston, P. Kyle McCarter, and Stefan J. Wimmer of “An Inscribed Altar from the Khirbat Ataruz Moabite Sanctuary” (the editio princeps of the new Moabite inscriptions from Khirbat Ataruz, Jordan) published in the journal Levant, and author of “A Curse of the Division of Land: A New Reading of the Bukān Aramaic Inscription Lines 9–10,” in Biblical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies in Honor of P. Kyle McCarter Jr. (SBL Press 2022), along with several reference articles in the Dictionary of Daily Life in Biblical and Post-biblical Antiquity. He has been actively involved in archaeological fieldwork and grant-funded epigraphic research projects in Jordan.

Prof. Christopher A. Rollston is Professor of Northwest Semitic languages and literatures in the Department of Classical and Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations at George Washington University. He holds an M.A. and Ph.D. from Johns Hopkins University's Department of Near Eastern Studies and is the editor of Maarav and co-editor of BASOR (Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research). Rollston is the editor of Enemies and Friends of the State: Ancient Prophecy in Context and the author of Writing and Literacy in the World of Ancient Israel: Epigraphic Evidence from the Iron Age as well as many academic articles such as “Scribal Curriculum during the First Temple Period: Epigraphic Hebrew and Biblical Evidence.” He is an expert in ancient epigraphy and blogs about new finds and current debates on www.rollstonepigraphy.com.

Essays on Related Topics: