Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Deathblows to a Pregnant Woman – What Restitution Was Required?

pixy.org, adapted

Exodus 21:22-25: Accidental Injuries in a Public Brawl

The talionic principle (often referred to by the Latin, ius talionis, based on its use in Roman law),[1] appears in the Torah’s “wisdom laws” of מִּשְׁפָּטִים in the case of homicide, where a pregnant woman is accidentally killed in a fight.[2] This scenario features also in the legal collections of the ancient Near East, where “a diversity of enforceable rules” existed to redress such losses.[3]

Financial Compensation for Miscarriage

The accidental injury of a pregnant woman in a public brawl was of particular significance in the monumental legal collections of Mesopotamia, where the life of a married women together with her unborn child, represented the highest single individual loss an average adult male householder could sustain, outside of his fixed assets.

As was the case elsewhere in biblical law such assaults were perceived as an infringement of male property rights, rather than an attack on the personhood of the woman.[4] In the NJPS translation, the words [bracketed] are not individually represented in the Hebrew:

שמות כא:לד וְכִי יִנָּצוּ אֲנָשִׁים וְנָגְפוּ אִשָּׁה הָרָה וְיָצְאוּ יְלָדֶיהָ וְלֹא יִהְיֶה אָסוֹן עָנוֹשׁ יֵעָנֵשׁ וְנָתַן בִּפְלִלִים.

Exod 21:34 When men fight and one of them pushes a pregnant woman and a miscarriage results (literally, “her child comes out”) but no [other] damage ensues, the one responsible he shall be fined, [according] as the woman’s husband may exact from him the payment to be based on reckoning.

Here if the woman lost her unborn child in the affray, her assailant had to pay a fine to her husband, which was subject to adjudication—possibly by an elder—and where the assessed amount was “based on reckoning.”

Liability and Restitution for the Mother’s Death

The focus then shifts to the injuries sustained by the mother, which are differentiated as fatal (Exod 21.23) and non-fatal (Exod 21.24),[5] as follows:

- Liability for the Loss of Life of the Mother

שמות כא:כג וְאִם אָסוֹן יִהְיֶה וְנָתַתָּה נֶפֶשׁ תַּחַת נָפֶשׁ.

Exod 21:23 But if [other] damage ensues, you will give a life for a life.

- Liability for Non-Fatal Physical Injuries of the Mother

שמות כא:כד עַיִן תַּחַת עַיִן שֵׁן תַּחַת שֵׁן יָד תַּחַת יָד רֶגֶל תַּחַת רָגֶל. כא:כה כְּוִיָּה תַּחַת כְּוִיָּה פֶּצַע תַּחַת פָּצַע חַבּוּרָה תַּחַת חַבּוּרָה.

Exod 21:24 Eye for eye; tooth for tooth; hand for hand; foot for foot; 21:25 burn for burn; wound for wound; bruise for bruise.

Leaving aside the woman’s non-fatal injuries, what exactly was meant by the requirement “you will give a life for a life”?

Interpretation 1—Capital Punishment: The Killer is Killed

The common explanation of this law is that the assailant is to receive the same assault as he inflicted, i.e., he was to be killed. The same would hold for any other injury inflicted upon the woman as the subsequent eye, tooth, foot, injuries imply. This, however, is highly problematic because elsewhere in the Covenant Collection, capital punishment was required for intentional murder, rather than manslaughter (Exod 21:12–14).[6] Moreover, if the assailant’s own life was to be taken, this would have been stated as מוֹת יוּמָת “he shall be put to death.”[7]

Interpretation 2—Monetary Compensation

The rabbinic view holds that “a life for a life” denotes monetary compensation.[8] Likewise, Brandeis University’s David Wright, argues that the use of the root נ.ת.נ (“to give”) demonstrates that this is really a requirement for financial compensation.[9] Yet if this was intended, the law would have stated, “but if [other] damage ensues, the one responsible he shall be fined” as was explicit in Exod 21:22, where the assailant was fined for the loss of the unborn child. This would be the appropriate biblical language if, indeed, monetary compensation was intended.[10]

Interpretation 3— Vicarious Life Substitution

A third approach is suggested in the broader framework of legal traditions, where the eminent German-Jewish historian of ancient law, David Daube (1909–1999), maintained that Exodus 21:23 meant ‘”in place of,” or “because of,” so that נֶפֶשׁ תַּחַת נָפֶשׁ, (“a life for a life,”) denoted “a life in place of a life.” This, he maintained, implied human substitution as a form of compensation.[11]

Daube was particularly careful not to specify whether the substitute was to be killed or provided as a living replacement. His interpretation, however, is verified by the conventional use of the preposition תחת throughout the Hebrew Bible, when it appears in relation to individual humans.[12]

This raises the inevitable question: Whose life could feasibly replace that of the dead mother in this case? Cornelis Houtman, Professor Emeritus of Old Testament at Protestant Theological University (Amsterdam) explains as follows:

For retaliation it is not the life, the eye etc. of the offender that is demanded, but the life, etc. of his wife.… One who violates that rule is going to feel the consequences in the loss or maiming of his own wife. So the equilibrium between the parties is restored. The regulation is especially in the nature of a preventative (cf. Deut 19:20), addressing the attack on a man’s most precious possession, the woman, the one who could give him offspring.[13]

These comments highlight the economic reality that a pregnant female would command additional value based on her future child-bearing potential, and that the legal equivalence (or “equilibrium”) dictated that only one wife’s life, or limb, was legitimate restitution for loss or injury to the assailant’s wife’s life or limb. In Exodus 21:23, therefore, the talionic principle defined not only the extent of the physical injury, but also restricted its application to the wife of the man who inflicted the blows. This is entirely different to the prevalent assumption that the principle demanded physical mutilation of the assailant, corresponding to the injury he had inflicted on the woman.

Houtman’s observation thus identifies the “life for life” requirement specifically as a form of vicarious punishment, namely a “punishment that is imposed not on the culprit but upon another person who stands in a particular relationship to the culprit, for example, employer, father or son.”[14]

A Wife for a Wife?

In this context Bernard Jackson, the British Jewish professor of legal history and Jewish studies, and a student of Daube, further suggests that in the Covenant Collection נפש תחת נפש “a life for a life” refers to live, human, substitution, where

[T]he sanction provided in the apodosis is not death, but rather substitution of persons — quite literally, “a soul for a soul” (but a live soul, not a dead one). This explains why mot yumat is not used, and is supported by ancient Near Eastern parallels, particularly MAL A50, which uses an almost identical expression, napšate (cf. nefesh) umallā.[15]

In practice, this option to provide a live replacement could then encourage further negotiations in which the offender might substitute the life of his own daughter, sister, or even female slave for the life of the dead women. In the absence of an available female substitute, it may then have been possible to reimburse the victim’s husband with the full payment of his original bride-price with interest. This would enable him to obtain another wife, based on the “reckoning” acknowledged in Exodus 21:22, despite the fact that this was not ab initio the intent of the Torah’s law.

The Principle of napšāte umallā in the Middle Assyrian Laws

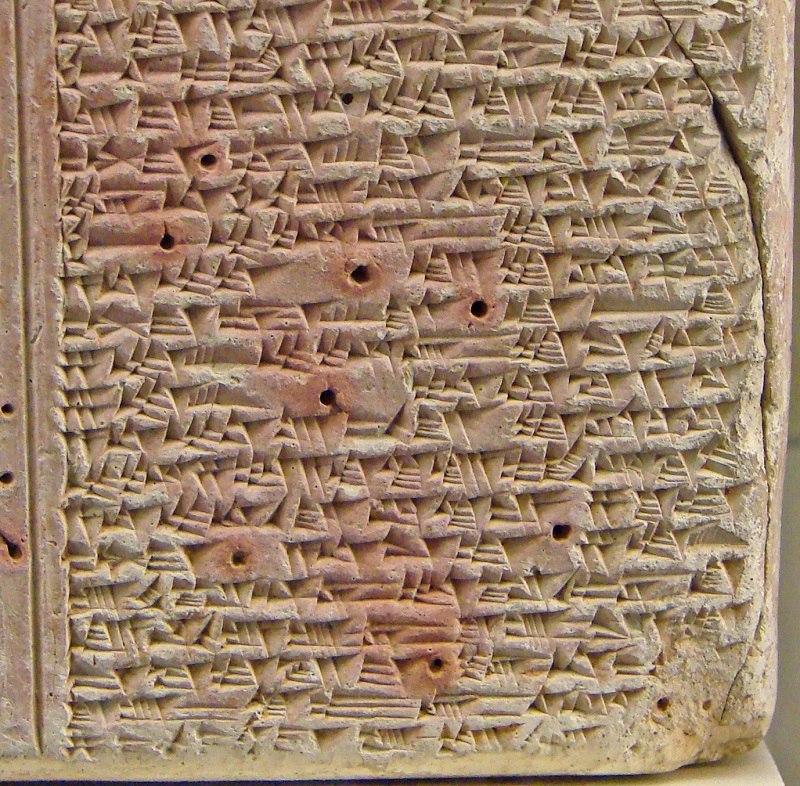

The Middle Assyrian Laws, Tablet A. University of Oxford CC 4.0

Jackson’s reconstruction is supported by earlier cognates from the Middle Assyrian Laws,[16] as transliterated and translated by Godfrey Driver and John Miles in 1935,[17] who clarify the principle, kīmā ša libbiša napšāte umallā “he pays on the principle of a life.” This principle applied both to the death of the assailant (in the event of his causing a married woman’s death), but also where (unspecified live or dead) substitution was intended.[18]

This is immediately evident from the subsequent provision (MAL A51), where the principle was omitted but where a fine of 2 talents of lead (equivalent to 7,200 shekels) was explicit. As Driver and Miles explained,

It will at once have been noticed that, in all cases where the clause napšāte umallā occurs, the punishment is a form of talion. In §51, on the contrary, where it does not occur, the penalty is a mere monetary compensation into which talion does not enter.[19]

Their translation is particularly preferred to that of Martha Roth’s, which provided “he shall make full payment of a life for her fetus,” to imply monetary compensation.[20] This preference is substantiated further by available case law,[21] as noted by the late German Protestant theologian, Horst Seebas:

Interesting on account of the legal notions embodied are the texts dealing with the principle of ‘a life for a life’, e.g., ‘If they do not discover the one who murdered him, they will deliver 3 persons as a fine (umallu ‘make full’); in the case of an unborn child: ‘He gives restitution as for a person (napšāte umallā); a pretrial settlement: ‘Do not go to court against me. I will replace your slave with a person (napšāti ša qallika ūšallamka).[22]

This account of the “life for life,” principle in the CC, and its relationship to Middle Assyrian law, as proposed by Driver and Miles, together with Bernard Jackson, is further informed by available counterparts in ancient Babylonian legal tradition.

Babylonian Distinctions: Vicarious Killing, Monetary Fines, Life Substitution, and Capital Punishment

The underlying concept of vicarious punishment is also attested in the parallel provisions from the Laws of Hammurabi (LH), a collection that is widely acknowledged as influencing the CC.[23] At this point, it is worth emphasising that no single ancient collection covers the entire social spectrum of assailants and victims, let alone the full range of possible injuries – but also that the incidence of mental and emotional harm is never addressed in any of these contexts.

Here, in LH 209–214, damages for striking a pregnant woman are indicated only when the fatal blow has been struck by an awīlu, i.e., a free man who has greater rights and privileges than other social classes in Hammurabi’s Babylon,[24] as follows:

- Mārat awīlim—a woman from his own higher class: “if that woman should die, they shall kill his daughter.” [25]

- Mārat muškēnim—a woman from the lower, or “commoner,” class: The assailant is fined thirty shekels of silver.[26]

- Amat awīlim—a female slave belonging to an awīlu(m): The assailant is fined twenty shekels of silver.[27]

Aside from the vicarious killing of the assailant’s own daughter, the purpose of the financial penalties in LH 212 & 214 was to pay the going market rate to the property-owning male, compensating him for his financial loss. The additional regulations addressing damages incurred by a negligent builder are particularly illuminating where the differentiation between capital punishment, vicarious killing, and vicarious “life” substitutions are clear:

Capital Punishment of the Assailant: (LH 229) “If a builder constructs a house for an awīlu but does not make his work sound, and the house that he constructs collapses and causes the death of the householder, that builder shall be killed.”

Vicarious Killing: (LH 230) “If it should cause the death of the son of the householder, they shall kill a son of that builder.”

Live, Human, Substitution: (LH 231) “If it should cause the death of a slave of the householder, he shall give to the householder a slave (of comparable value) for the slave.”

In this last case, the resonance of wardam kīma wardim “a slave of comparable value for the slave,” (LH 231) with נפש תחת נפש “a life for a life” is notably apparent. Similarly, the instruction “he shall give to the house-holder” (ana bēl bītim inaddin) indicates that inaddin, from the verb nadanu(m) “to give” is the etymological equivalent of נתן in Exodus 21:23.

No Capital Punishment or Vicarious Killing for Accidental Homicide

In short, the death of the assailant was never intended in Exodus 21:22–25, even if both the woman and her child had been fatally injured. In the worst-case scenario, the assailant would have to pay money (or its equivalent in metals, grain, cattle, or livestock) for the loss of life of the child and ideally replace the deceased wife with a living female substitute.

If the assailant did not have either a daughter or female slave, there would then be no barrier to his offering financial compensation as an alternative, to allow the victim’s husband to acquire a replacement for his dead wife. According to Exodus 21:22, this amount would have been negotiable, and subject to the victim’s husband’s assent.

Thus the “life for a life” principle in the CC denoted vicarious, but live, human substitution, rather than capital punishment of the assailant, vicarious killing, or monetary compensation. This resolution, however repellent it seems now, made practical sense in ancient societies, where a man whose household economy would suffer, through the death of his wife, would have needed a functional (i.e. childbearing and/or childrearing) replacement.

In Exodus 21:23, therefore, the principle of נפש תחת נפש “a life for a life” was no metaphorical abstraction, devoid all practical function and legal significance, but rather one that retained an unmistakable impression of Middle Assyrian law, in its particular relationship to the principle kīmū ša libbiša napšate umallā, where the assailant “pays (on the principle of) a life (for a life).”[28]

While there is no evidence of the statutory force of this principle, or its historical implementation in ancient Israelite or Judaean societies, Eckart Frahm rightly concludes:

This ambivalence of the role of God and his law in the monotheistic religions, emancipating on one hand and repressive on the other, is to some extent owed to Israel’s and Judah’s encounter with the Assyrian empire and [remains] one of the most important legacies of this state until today.[29]

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

February 20, 2020

|

Last Updated

February 8, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Sandra Jacobs was awarded her doctorate on physical disfigurement and corporal punishment in ancient Hebrew and cuneiform legal sources in 2010, supervised by Bernard Jackson, at the University of Manchester. Her research was published as The Body as Property: Physical Disfigurement in Biblical Law (London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic Press, 2014 repr. in 2015). From 2010-2016 she worked as Book Review Editor for Strata: The Bulletin of the Anglo-Israel Archaeological Society. During 2016-2019 she worked on the Leverhulme International Network project, Dispersed Qumran Cave Artefacts and Archives, at King’s College, London, where she is currently a Visiting Research Fellow. She continues also to teach at Leo Baeck College, London.

Essays on Related Topics: