Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Enallage in the Bible

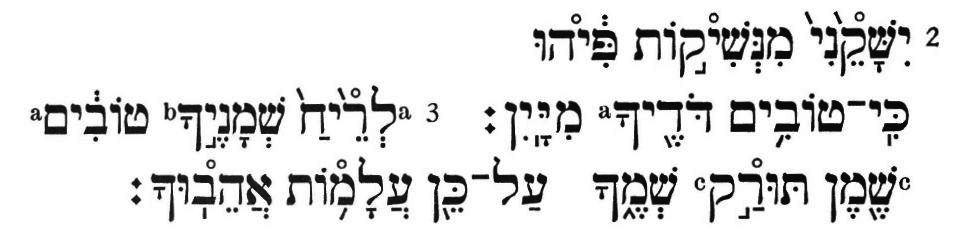

The beginning of Song of Songs in the ‘Almanzi Pentateuch.’ Lisbon, Portugal 15th C. British Library

Translating Song of Songs 1:2[1]

Following the book’s superscription,[2] the Song of Songs begins:

| NJPS | MT | NRSV |

| Oh, Give me the kisses of your mouth, |

יִשָּׁקֵ֙נִי֙ מִנְּשִׁיק֣וֹת פִּ֔יהוּ

|

Let him kiss me with the kisses of his mouth! |

| For your love is more delightful than wine. |

כִּֽי־טוֹבִ֥ים דֹּדֶ֖יךָ מִיָּֽיִן׃

|

For your love is better than wine, |

יִשָּׁקֵנִי is the third person singular verb, “may he kiss (me),” as is the suffix of “mouth,” פִּיהוּ, “his mouth,” thus the NRSV follows the Hebrew more closely. In fact, NJPS includes a note saying, “Heb. ‘Let him give me of the kisses of his mouth!’” Why, then, does the NJPS, which according to its title page is “According to the Traditional Hebrew Text,” change the person of this colon from the third to the second person?

Often, when NJPS differs from MT, it is emending the text, whether it says so or not.[3] But here, no emendation is mentioned in a note and none of the versions support this reading. The Dead Sea Scroll 6QCanticles, though fragmentary, preserves the third person reading of the verb [4]ישקני.

The translation of NJPS is an attempt to make the verse as a whole read better. The second part of the verse reads:

כִּֽי־טוֹבִ֥ים דֹּדֶ֖יךָ מִיָּֽיִן

For your lovemaking[5] is more delightful than wine.

The male lover here is referred to in the second person—“your lovemaking,” דֹּדֶיךָ. Thus, the NJPS translation makes the verse read more consistently, referring to the male lover throughout in the second person.[6] But is this smoothing out justified?

How Verses 2-3 Fit Together

The NJPS rendering assumes that both parts of verse two belong together, and the verse is a typical couplet or bicolon, namely two cola or versets (to use Robert Alter’s term) that function together as a unit. This is certainly possible, and even initially likely, given that the bicolon is “standard in [Biblical] Hebrew poetry.”[7] But as we continue reading the Song, we see that verse 3 has three cola, which is much less frequent:

לְרֵ֙יחַ֙ שְׁמָנֶ֣יךָ טוֹבִ֔ים

שֶׁ֖מֶן תּוּרַ֣ק שְׁמֶ֑ךָ

עַל־כֵּ֖ן עֲלָמ֥וֹת אֲהֵבֽוּךָ׃

Your ointments are delightful to smell,

Your name is like finest oil—

Therefore do maidens love you.[8]

The first colon of v. 3 parallels the final colon of v. 2, suggesting that the beginning of v. 3 really belongs with v. 2, and we should read the two cola together as a couplet or bicolon:

כִּֽי טוֹבִ֥ים דֹּדֶ֖יךָ מִיָּֽיִן

לְרֵ֙יחַ֙ שְׁמָנֶ֣יךָ טוֹבִ֔ים

For your lovemaking is more delightful than wine;

Your ointments are delightful to smell.

Basic principles of biblical poetic parallelism suggest that this is a good reading. The words דֹּדֶיךָ, “your love-making” and שְׁמָנֶיךָ, “your ointments,” each plural nouns with second masculine singular suffixes (“your”), would be grammatically parallel. On the semantic level, each verse half would repeat the word טוֹבִים, “good, delightful,” and יָּיִן, “wine,” of the first half would find its parallel in שׁמן, “ointments, oil” in the second half. “Wine” and “oil” are often used together, or in parallelism elsewhere,[9] and the two are found in parallelism in Song of Songs 4:10:

מַה־יָּפ֥וּ דֹדַ֖יִךְ אֲחֹתִ֣י כַלָּ֑ה

מַה־טֹּ֤בוּ דֹדַ֙יִךְ֙ מִיַּ֔יִן

וְרֵ֥יחַ שְׁמָנַ֖יִךְ מִכָּל־בְּשָׂמִֽים׃

How sweet is your lovemaking, my sister, my bride!

How much more delightful your lovemaking than wine,

Your ointments more fragrant than any spice!

Indeed, the standard scholarly version of the complete Hebrew Bible, Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia, “reversifies” or reorganizes the poetic lines in vv. 2-3 to read:

Several commentaries argue similarly.[10]

In this reading, the first three words of v. 2 are either an introductory colon,[11] or perhaps a title of the song that follows.[12] The end of v. 2 and all of v. 3 would be a quatrain framed by כִּי, “for, because” and עַל־כֵּן, “therefore,” a well-attested structure.[13]

This reversification is possible, but not fully compelling. An initial colon, a line that stands alone introducing a poem, may be found elsewhere, and titles are found in the Bible.[14] But neither is common, and the tradition of versification in the MT carries some weight,[15] suggesting that perhaps v. 2 should not be broken up. But if so, should we follow NJPS, reading the entire verse as a reference to the male lover in the second person, rather than following MT, and seeing the lover switch from third (“may he” “your [masculine singular] kisses”) to second person (“your lovemaking”)?

The Change in Person

The problem of the change in person was noted by several of the medieval Jewish commentators, who as a matter of course accepted the standard versification of MT. Rashbam (Rabbi Samuel son of Meir, 1060-1135),[16] the grandson of Rashi, glosses דֹּדֶיךָ, “your lovemaking” of v. 2:

פעמים שמשוררת הלה כאילו היא מדברת עם אוהבה, ופעמים שמספרת לריעותיה על שאינו אצלה.

Sometimes the bride writes her poem as if she is speaking to her lover and sometimes as if she is telling her friends about his not being with her.[17]

Abraham ibn Ezra similarly suggests:

משל – נערה חוץ מן המדינה בכרמים ראתה רועה עובר וחשקה בו והתאותה בלבה ואמרה מי יתן ישקני פעמים רבות וכאלו שמע אותה ואמרה לו: כי טובים דודיך מיין…

A maiden outside the city… saw a shepherd passing by, desired him, and lusted, saying, “If only he would kiss me.” And then, as if he had heard her, she said to him “for your love is better….”[18]

The Italian rabbinic scholar Isaiah of Trani the elder (Rid, ca. 1180 – ca.1250), whose commentary is found the Haketer edition of the rabbinic Bible, glosses v. 2,

ומדבר פנים בפנים ושלא בפנים.

The verse speaks [sometimes as is they are] face to face and [sometimes] as if they are not both present.

Although not stated explicitly, these glosses are a reaction to the sudden change in person in the middle of v. 2.[19]

Throughout Song of Songs, changes in person between verses denote shifts in the speaker; these are typically unmarked by “he said” or “she said,” but are clear from context. For example, 5:1-2 reads:

ה:א בָּ֣אתִי לְגַנִּי֮ אֲחֹתִ֣י כַלָּה֒

אָרִ֤יתִי מוֹרִי֙ עִם־בְּשָׂמִ֔י

אָכַ֤לְתִּי יַעְרִי֙ עִם־דִּבְשִׁ֔י

שָׁתִ֥יתִי יֵינִ֖י עִם־חֲלָבִ֑י

אִכְל֣וּ רֵעִ֔ים

שְׁת֥וּ וְשִׁכְר֖וּ דּוֹדִֽים׃

ה:ב אֲנִ֥י יְשֵׁנָ֖ה וְלִבִּ֣י עֵ֑ר

ק֣וֹל ׀ דּוֹדִ֣י דוֹפֵ֗ק

פִּתְחִי־לִ֞י אֲחֹתִ֤י

רַעְיָתִי֙ יוֹנָתִ֣י תַמָּתִ֔י

שֶׁרֹּאשִׁי֙ נִמְלָא־טָ֔ל

קְוֻּצּוֹתַ֖י רְסִ֥יסֵי לָֽיְלָה׃

5:1 I have come to my garden, my own, my bride;

I have plucked my myrrh and spice,

Eaten my honey and honeycomb,

Drunk my wine and my milk.

Eat, lovers, and drink:

Drink deep of love!

5:2 I was asleep, but my heart was wakeful.

Hark, my beloved knocks!

“Let me in, my own,

My darling, my faultless dove!

For my head is drenched with dew,

My locks with the damp of night.”

Grammar and content make it clear that v. 1 is spoken by the man, and v. 2 by the woman. (This is one of many cases where the thirteenth century chapter divisions are misleading.) But this type of shift, which is frequent in the poem, is between verses, not, as in 1:2, in a single verse.

The Oxford Anonymous Peshat Commentary

The most detailed discussion of the change of person in Song of Songs 1:2 in the commentary literature, medieval or modern, is found in the anonymous commentary from the Bodleian Library of Oxford University.[20] This commentary is known only in a single copy; it now begins with 1:2, so it is probable that its title page, which included its author, was lost. It mostly likely dates for the late twelfth century,[21] and is one of two medieval Jewish commentaries on the Song that do not interpret it allegorically.[22]

The Bodleian manuscript opens with a rejection of the position of ibn Ezra (mixed up a bit with that of Rashbam), noting instead:

ואני או[מר] שכיוצא בפסוק זה מצינו הרבה פסוקים…

But I say that there are many other verses like this verse…[23]

It then goes on to list fourteen verses that show similar changes in person, divided into three categories: those that, like our verse, switch from third to second person, those that switch from first to third person, and those that contain other changes in person.[24]

The following three verses belong to the first category (Mic 7:19):

Micah 7:19

יָשׁ֣וּב יְרַֽחֲמֵ֔נוּ

יִכְבֹּ֖שׁ עֲוֹֽנֹתֵ֑ינוּ

וְתַשְׁלִ֛יךְ בִּמְצֻל֥וֹת יָ֖ם

כָּל־חַטֹּאותָֽם׃

He will take us back in love;

He will cover up our iniquities;

You will hurl into the depths of the sea

all their sins.

Isaiah 1:29

כִּ֣י יֵבֹ֔שׁוּ

מֵאֵילִ֖ים אֲשֶׁ֣ר חֲמַדְתֶּ֑ם

וְתַ֨חְפְּר֔וּ

מֵהַגַּנּ֖וֹת אֲשֶׁ֥ר בְּחַרְתֶּֽם׃

Truly, they[25] shall be shamed

Because of the terebinths you desired,

And you shall be confounded

Because of the gardens you coveted.

Job 17:10

וְֽאוּלָ֗ם כֻּלָּ֣ם תָּ֭שֻׁבוּ וּבֹ֣אוּ נָ֑א

וְלֹֽא־אֶמְצָ֖א בָכֶ֣ם חָכָֽם׃

But all of them,[26] come back now;

I shall not find a wise man among you.

As Japhet and Walfish have shown, all of the cases of grammatical person switching adduced in this commentary are based on the twelfth century Spanish philologist and lexicographer, Solomon ibn Parchon, who in turn has reworked the great Spanish grammarian and lexicographer Jonah ibn Janach (ca. 990-ca. 1055). Ibn Janach explained such changes as part of a more general theory of lexical substitution, where, “There are times when they [i.e. the biblical authors] use a certain word and its meaning is [that of] another. And they permit this because of the close association of the two works in genus, species, quality or any other matter.”[27] This would allow a biblical author, e.g., to use a third person verb where the second person is intended.

Ibn Janach offers over two hundred examples to support his idea.[28] Exactly how he understood substitution is debated by modern scholars; some believe that these may be de facto or covert emendations, suggesting that he thought “sound exegesis may require the restoration of a defective text,”[29]while others insist that “[i]t is self-evident that …these are not emendations.”[30] Many of the cases of substitution have been subjected to emendations by modern biblical scholars.[31]

Enallage

Many modern commentaries note the change of person in v. 2. In his 1977 Anchor Bible commentary on the Song, the first truly modern commentary on that book,[32] Marvin Pope notes:

The shift from third person to second has evoked various emendations to mitigate or eliminate the incongruity. Many moderns read yašqēnı̂, “let him make me drink,” or the imperative hašqēnı̂, “make me drink.” But these changes also necessitate alteration of “his mouth” to “your mouth.” … It seems best to leave the text unaltered, since enallage (shift in person) is common in poetry; cf. Deut 32:15; Isa 1:29; Jer 22:24; Micah 7:19; Psalm 23.[33]

Citing some of the same verses as the medievals, Pope has given the phenomenon isolated by ibn Janach, Parchon, and the anonymous commentator a name, “enallage,” from Greek ἐναλλαγή, enallagḗ, “interchange.” This rhetorical device was isolated in classical antiquity, named in the renaissance, and is used by many authors;[34] it is cited in some dictionaries of literary terms.[35] For example, Shakespeare employs a form of enallage, in this case interchange of the singular and plural, in Henry IV Part 2, I, ii: “Is there not wars?” But enallage has never been studied comprehensively in the Bible; in fact, the most thorough treatments of the phenomenon in the Bible are from medieval Jewish works that concern stylistics.

Enallage in Deuteronomy 32:15

Pope adduces Deuteronomy 32:15 as his first example of enallage. It is from the long poem known in Hebrew after its first word, הַאֲזִינוּ, “hearken,” which claims to narrate the history of ancient Israel and predict its future; Israel is typically referred to in the third person throughout. In the MT, 32:15 opens and closes with Israel described in the third person, but in the middle of the verse, Israel is addressed in the second person:

וַיִּשְׁמַ֤ן יְשֻׁרוּן֙ וַיִּבְעָ֔ט

שָׁמַ֖נְתָּ עָבִ֣יתָ כָּשִׂ֑יתָ

וַיִּטֹּשׁ֙ אֱל֣וֹהַ עָשָׂ֔הוּ

וַיְנַבֵּ֖ל צ֥וּר יְשֻׁעָתֽוֹ׃

So Jeshurun [= Israel] grew fat and kicked;

You grew fat and you grew gross and you grew coarse;

He forsook the God who made him;

and spurned the Rock of his support.[36]

It is unclear why here the poem suddenly switches form talking about Israel to talking to Israel.[37]

Enallage in Psalm 23

Pope also notes that Ps 23, one of the most famous psalms, uses enallage; this example is slightly different from Song of Songs 1:2 and Deut 32:15 because the shifting is within the larger psalm or chapter, rather than within a single verse. The first three verses refer to God in the third person:

תהלים כג:א מִזְמ֥וֹר לְדָוִ֑ד יְ-הוָ֥ה רֹ֝עִ֗י לֹ֣א אֶחְסָֽר׃ כג:ב בִּנְא֣וֹת דֶּ֭שֶׁא יַרְבִּיצֵ֑נִי עַל־מֵ֖י מְנֻח֣וֹת יְנַהֲלֵֽנִי׃ כג:גנַפְשִׁ֥י יְשׁוֹבֵ֑ב יַֽנְחֵ֥נִי בְמַעְגְּלֵי־צֶ֝֗דֶק לְמַ֣עַן שְׁמֽוֹ׃

Ps 23:1 A psalm of David. YHWH is my shepherd; I lack nothing. 23:2 Hemakes me lie down in green pastures; he leads me to water in places of repose; 23:3 He renews my life; he guides me in right paths as befits His name.

The following two verses refer to God in the second person:

כג:ד גַּ֤ם כִּֽי־אֵלֵ֨ךְ בְּגֵ֪יא צַלְמָ֡וֶת לֹא־אִ֘ירָ֤א רָ֗ע כִּי־אַתָּ֥ה עִמָּדִ֑י שִׁבְטְךָ֥ וּ֝מִשְׁעַנְתֶּ֗ךָ הֵ֣מָּה יְנַֽחֲמֻֽנִי׃ כג:ה תַּעֲרֹ֬ךְ לְפָנַ֨י ׀ שֻׁלְחָ֗ן נֶ֥גֶד צֹרְרָ֑י דִּשַּׁ֖נְתָּ בַשֶּׁ֥מֶן רֹ֝אשִׁ֗י כּוֹסִ֥י רְוָיָֽה׃

23:4 Though I walk through a valley of deepest darkness, I fear no harm, for You are with me; Your rod and Yourstaff—they comfort me. 23:5 Youspread a table for me in full view of my enemies; You anoint my head with oil; my drink is abundant.

The final verse returns to speaking of, not to God, again using the third person:

כג:ו אַ֤ךְ ׀ ט֤וֹב וָחֶ֣סֶד יִ֭רְדְּפוּנִי כָּל־יְמֵ֣י חַיָּ֑י וְשַׁבְתִּ֥י בְּבֵית־יְ֝הוָ֗ה לְאֹ֣רֶךְ יָמִֽים׃

23:6 Only goodness and steadfast love shall pursue me all the days of my life, and I shall dwell in the house of YHWH[not “Your house”] for many long years.

צריך עיון: Further Research Required

Academic biblical scholarship in some cases has made little more progress than the medieval Jewish commentators who were so attuned to biblical stylistics. Thus, the reasons for grammatical shifts in person in Deut 32:15, Psalm 23, Song of Songs 1:2, and in many other cases of enallage, still remain unclear. Are they all textual errors? (I doubt it—though some may be.) Is this a stylistic devise for variation, which is common in biblical poetry, breaking up the monotony created by parallelism?[38] Alternatively, is each of these changes meaningful for interpretation? Do different books use enallage for different reasons?

Until a modern scholar completes the work started by the medievals and offers a comprehensive theory of how enallage is used, none of these questions can be answered, and our understanding of Song of Songs 1:2 and many other texts will remain impoverished.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

April 2, 2018

|

Last Updated

March 25, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Marc Zvi Brettler is Bernice & Morton Lerner Distinguished Professor of Judaic Studies at Duke University, and Dora Golding Professor of Biblical Studies (Emeritus) at Brandeis University. He is author of many books and articles, including How to Read the Jewish Bible (also published in Hebrew), co-editor of The Jewish Study Bible and The Jewish Annotated New Testament (with Amy-Jill Levine), and co-author of The Bible and the Believer (with Peter Enns and Daniel J. Harrington), and The Bible With and Without Jesus: How Jews and Christians Read the Same Stories Differently (with Amy-Jill Levine). Brettler is a cofounder of TheTorah.com.

Essays on Related Topics: