Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Gilgal: YHWH’s Footprints in the Land of Israel

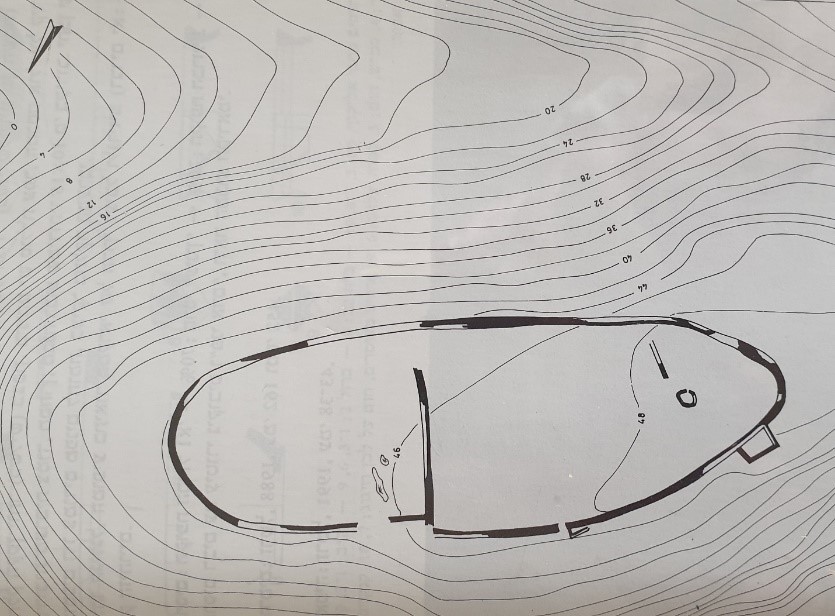

Bedhat esh-Shaʿab / Argaman, one of the proposed sites for “the Gilgal,” photo taken in 2009 by Adam Zertal, z”l. Wikimedia

In Deuteronomy 11, Moses tells the Israelites that when they cross over into the Cisjordan, they should head to the area of Mount Gerizim and Mount Ebal:

דברים יא:כט וְהָיָה כִּי יְבִיאֲךָ יְ־הוָה אֱלֹהֶיךָ אֶל הָאָרֶץ אֲשֶׁר אַתָּה בָא שָׁמָּה לְרִשְׁתָּהּ וְנָתַתָּה אֶת הַבְּרָכָה עַל הַר גְּרִזִים וְאֶת הַקְּלָלָה עַל הַר עֵיבָל. יא:ל הֲלֹא הֵמָּה בְּעֵבֶר הַיַּרְדֵּן אַחֲרֵי דֶּרֶךְ מְבוֹא הַשֶּׁמֶשׁ בְּאֶרֶץ הַכְּנַעֲנִי הַיֹּשֵׁב בָּעֲרָבָה מוּל הַגִּלְגָּל אֵצֶל אֵלוֹנֵי מֹרֶה. יא:לא כִּי אַתֶּם עֹבְרִים אֶת הַיַּרְדֵּן לָבֹא לָרֶשֶׁת אֶת הָאָרֶץ אֲשֶׁר יְ־הוָה אֱלֹהֵיכֶם נֹתֵן לָכֶם...

Deut 11:29 When YHWH your God brings you into the land that you are about to enter and possess, you shall pronounce the blessing at Mount Gerizim and the curse at Mount Ebal—11:30 Both are on the other side of the Jordan, beyond the west road that is in the land of the Canaanites who dwell in the Arabah—near the Gilgal, by the terebinths of Moreh. 11:31 For you are about to cross the Jordan to enter and possess the land that YHWH your God is assigning to you….

Moses later repeats this command in Deuteronomy 27, which mandates setting up an altar there that should serve as the site for blessing and cursing Israel.[1]

This scenario supposes that the Israelites should cross the Jordan River, and then head west to a place near the terebinths of Moreh, which we know from elsewhere is in the vicinity of Shechem:

בראשית יב:ו וַיַּעֲבֹר אַבְרָם בָּאָרֶץ עַד מְקוֹם שְׁכֶם עַד אֵלוֹן מוֹרֶה...

Gen 12:6 Abram passed through the land as far as the site of Shechem, at the terebinth of Moreh…

But it is more difficult to identify the Gilgal which is said to be opposite Gerizim and Ebal.

Where Is the Gilgal?

Although Deuteronomy 11:30 suggests that the Gilgal is in the vicinity of Shechem, other biblical passages place it elsewhere.

Near Jericho—The book of Joshua describes how the Israelites cross from Shittim in the Transjordan to the Gilgal near Jericho:

יהושע ד:יט וְהָעָם עָלוּ מִן הַיַּרְדֵּן בֶּעָשׂוֹר לַחֹדֶשׁ הָרִאשׁוֹן וַיַּחֲנוּ בַּגִּלְגָּל בִּקְצֵה מִזְרַח יְרִיחוֹ.

Josh 4:19 The people came up from the Jordan on the tenth day of the first month, and encamped at Gilgal on the eastern border of Jericho.[2]

This places the Gilgal further south than the Gilgal of Deuteronomy 11:30, and closer to the Jordan River.

Near Bethel—A third set of sources place Gilgal in the vicinity of Bethel and Mitzpeh, in the heartland of the Samarian hill country, in the south of Ephraim/north of Benjamin:

שמואל א ז:טו וַיִּשְׁפֹּט שְׁמוּאֵל אֶת יִשְׂרָאֵל כֹּל יְמֵי חַיָּיו. ז:טז וְהָלַךְ מִדֵּי שָׁנָה בְּשָׁנָה וְסָבַב בֵּית אֵל וְהַגִּלְגָּל וְהַמִּצְפָּה וְשָׁפַט אֶת יִשְׂרָאֵל אֵת כָּל הַמְּקוֹמוֹת הָאֵלֶּה. ז:יז וּתְשֻׁבָתוֹ הָרָמָתָה כִּי שָׁם בֵּיתוֹ...

1 Sam 7:15 Samuel judged Israel as long as he lived. 7:16 Each year he made the rounds of Bethel, the Gilgal, and Mizpah, and acted as judge over Israel at all those places. 7:17 Then he would return to Ramah, for his home was there…

The story of Elijah’s ascent to heaven (2 Kings 2:1), the complex of stories about the Gibeonites and Joshua (Josh 9:6, 10:7), and various stories about Saul (1 Sam 11–15) likely assume this location for the Gilgal.

We thus have at least three different locations for the Gilgal in the Bible. This point was already explored in depth by the great German Bible scholar Ernst Sellin, in his 1917 book titled Gilgal: A Contribution towards the History of Israel’s Immigration into Palestine, which opens with the chapter “the Gilgal near Shechem.”[3]

What Is the Gilgal?

The etymology of Gilgal’s name explains its “movability.” Most Bible translations translate the term הַגִּלְגָּל as a proper name, “Gilgal,” but the Hebrew uses a definite article (הַ) before the word (גִּלְגָּל), implying it is more of a description than a proper name. The word gilgal means “circle” or, as the Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament (HALOT) suggests, “stone circle.”

Thus, there were multiple Gilgals because there were multiple sites encircled by a stone wall of sorts. When the text says “the gilgal,” then, it likely means something like “the nearest gilgal.” This use is thus similar to the way that people may now say, “I am going into the City today”—the particular city varies depending on the speaker’s location.

Archaeology assists us in locating these various gilgals.

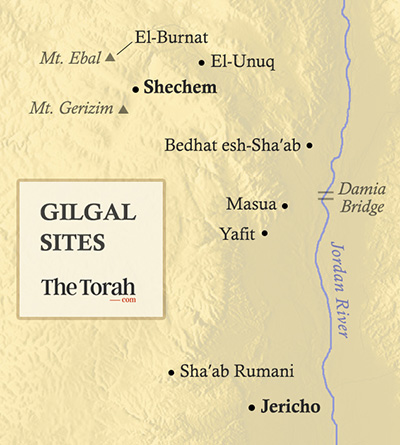

1) El-Unuq—An early Iron Age site known as el Unuq (Arabic for “the necklace”) is located in the Tirzah Valley not far from Shechem, a few kilometers from the Jordan River. It is an oval-ish site, surrounded by stones. As I know from my experience, looking westward from el-Unuq it is easy to see the worship site of el-Burnat on Mount Ebal.[4] Consequently, the late Haifa University archaeologist, Adam Zertal (1936–2015), who discovered the site as part of his extensive survey of the Manasseh hill country, identified it with “the Gilgal” of Deuteronomy 11:30, which is opposite Mount Ebal.

While no Gilgal site has yet to be identified near Jericho, at least four and maybe five others have been uncovered in various parts of the Jordan valley and the Israelite hill country.

2) Bedhat esh-Shaʿab—A very large site called Bedhat esh-Shaʿab, 169 meters long and 88 meters wide (at their largest points)[5] is located in the Jordan valley, near the village of Argaman.

3) Masua—Southwest of Bedhat esh-Sha’ab is another gilgal site, near the settlement of Masu’a.

4) Yafit—Just southeast of the Mesua site is another oval-shaped settlement, near the settlement of Yafit.

5) Shaʿab Rumani—Also known as Gilgal Binyamin, this is the smallest of the gilgal sites. It was discovered on the western part of Wadi al-Makuk, slightly south of the Rimmonim settlement. It is likely the Gilgal referenced in 1 Samuel 7:16, as one of the stops on Samuel’s circuit.[6]

6) El-Burnat—Finally, I would like to suggest that El-Burnat, the worship site on Mount Ebal, is also a gilgal of sorts, even if the Bible does not call it that.[7]

With one exception, all of these Gilgals, enclosed in this oval-ish shape, date to early Iron Age (first half of the 12th century B.C.E). Strikingly, this shape has nothing to do with the contours of the terrain. Instead, Zertal argues, the enclosures were built to reflect a specific design: a footprint.

The Footprint of YHWH

Placing of one’s feet on an area is symbolic of taking ownership. For example, God says to Abraham:

בראשית יג:יז קוּם הִתְהַלֵּךְ בָּאָרֶץ לְאָרְכָּהּ וּלְרָחְבָּהּ כִּי לְךָ אֶתְּנֶנָּה.

Gen 13:17 Up, walk about the land, through its length and its breadth, for I give it to you.

The walking throughout the land makes the land Abram’s. A similar process is evident in the opening of Joshua, where YHWH commands him:

יהושע א:ב ...וְעַתָּה קוּם עֲבֹר אֶת הַיַּרְדֵּן הַזֶּה אַתָּה וְכָל הָעָם הַזֶּה אֶל הָאָרֶץ אֲשֶׁר אָנֹכִי נֹתֵן לָהֶם לִבְנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל. א:ג כָּל מָקוֹם אֲשֶׁר תִּדְרֹךְ כַּף רַגְלְכֶם בּוֹ לָכֶם נְתַתִּיו כַּאֲשֶׁר דִּבַּרְתִּי אֶל מֹשֶׁה.

Josh 1:2 … Prepare to cross the Jordan, together with all this people, into the land that I am giving to the Israelites. 1:3 Every spot on which your foot treads I give to you, as I promised Moses.

Thus, Zertal argues, the giant footprints might represent the footprints of YHWH, and express the deity’s presence on earth. Support for this comes from how the Bible sometimes refers to places as YHWH’s footstool. For instance, the final chapter of Isaiah, which polemicizes against the rebuilding of the Temple:

ישעיה סו:א ...הַשָּׁמַיִם כִּסְאִי וְהָאָרֶץ הֲדֹם רַגְלָי אֵי זֶה בַיִת אֲשֶׁר תִּבְנוּ לִי וְאֵי זֶה מָקוֹם מְנוּחָתִי.

Isa 66:1 …The heaven is My throne and the earth is My footstool: Where could you build a house for Me, what place could serve as My abode?[8]

The anonymous prophet here emphasizes that if the whole world is YHWH’s footstool, i.e., his property, he need not dwell in a smaller temple. The implication that the Temple reflects God’s footstool is explicit in Ezekiel:

יחזקאל מג:ז …אֶת מְקוֹם כִּסְאִי וְאֶת מְקוֹם כַּפּוֹת רַגְלַי אֲשֶׁר אֶשְׁכָּן שָׁם בְּתוֹךְ בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל לְעוֹלָם…

Ezek 43:7 …This is the place of My throne and the place for the soles of My feet, where I will dwell in the midst of the people Israel forever….

Psalms partakes in this notion as well:

תהלים צט:ה רוֹמְמוּ יְ־הוָה אֱלֹהֵינוּ וְהִשְׁתַּחֲווּ לַהֲדֹם רַגְלָיו קָדוֹשׁ הוּא.

Ps 99:5 Exalt YHWH our God and bow down to His footstool; He is holy!

These texts refer to the Temple metaphorically as God’s footstool, and thus, Zertal argues, these foot-shaped enclosures may be ancient, anthropomorphic expressions of the same concept.[9] The footprints of YHWH in the land express his ownership of the land, and are probably ancient worship sites akin to the high places (bamot) mentioned in the Bible in a later period..

The Egyptian Connection

As a number of scholars have noted, the biblical imagery where treading on something represents or effects possession has parallels in the Egyptian concept of the Pharaoh using his enemies as a footstool. For example, Othmar Keel, Emeritus Professor of Old Testament at the University of Fribourg and expert on ancient Near Eastern art and iconography, draws attention to the verse in Psalms:

תהלים קי:א נְאֻם יְ־הוָה לַאדֹנִי שֵׁב לִימִינִי עַד אָשִׁית אֹיְבֶיךָ הֲדֹם לְרַגְלֶיךָ.

Ps 110:1 …YHWH said to my lord, “Sit at My right hand while I make your enemies your footstool.”

Keel connects this to a painting found in the tomb Hekaerneheh, which depicts the baby Pharaoh Thutmose IV sitting on his nursemaid’s lap, with his feet resting on a footstool depicting his enemies.[10] James Hoffmeier, an Egyptologist and Professor of Bible at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, notes that this same imagery appears in the tomb of Ken-Amun, depicting Pharaoh Amunhotep II as the child sitting on his nurse’s lap with his feet resting on his enemies.[11]

A further support that the footstool imagery in the Bible was borrowed from Egypt is the fact that the Egyptian word for footstool is hdm rdwj, cognate to the Hebrew. The late German Egyptologist Fritz Hintze argued that this similarity indicates a borrowing of the term and the concept.[12]

More broadly, the imagery of the Pharaoh stomping on his enemies with his feet goes as far back as the Narmer Pallete (ca, 3000 B.C.E.), and the gods would sometimes make this promise to Pharaoh. For instance, Amun promises Thutmose III, “I cause that your opponents fall under your sandals.”[13]

Making Israel and the Ebal Worship Site into YHWH’s Footstool

As Zertal argues that the early Israelite settlers were likely very influenced by Egyptian imagery,[14] but used it in a slightly different way. Instead of trying to express the dominance of an Israelite king over the local population[15] —the meaning of this motif in Egyptian iconography—they used it to express YHWH’s ownership of the land.

By building multiple footprint sites during the early settlement period, the Israelites symbolically established their new home as the domain of their god, YHWH. This is likely why Israel’s first major worship site, el-Burnat on Mount Ebal, was also built in the shape of YHWH’s footprint, to express that the site was YHWH’s footstool.[16]

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

September 4, 2020

|

Last Updated

December 22, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Zvi Koenigsberg worked alongside the late Prof. Adam Zertal throughout the Ebal excavations (1982-88). His long-term mentors include the late Prof. Benjamin Mazar and Prof. Yair Zakovitch. Koenigsberg wrote The Lost Temple of Israel, Academic Studies Press, Boston, 2015. Questions welcome at zvi@thelosttemple.com.

Essays on Related Topics: