Edit article

Edit articleSeries

How the Forbidden Fruit Became an Apple

Jarmoluk/Pixabay, adapted

The image of Adam, Eve, and the apple is a commonplace: from Roz Chast’s New Yorker cartoon of the serpent temptingly informing Eve: “It’s a Honeycrisp!” to the feminine hands cradling a cardinal red apple on the cover of Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight, the apple is everywhere the symbol of forbidden knowledge and temptation.[1] Yet the story of Adam and Eve in Genesis refers only to “the fruit” of the forbidden tree:

בראשׁית ג:ו וַתֵּרֶא הָאִשָּׁה כִּי טוֹב הָעֵץ לְמַאֲכָל וְכִי תַאֲוָה הוּא לָעֵינַיִם וְנֶחְמָד הָעֵץ לְהַשְׂכִּיל וַתִּקַּח מִפִּרְיוֹ וַתֹּאכַל וַתִּתֵּן גַּם לְאִישָׁהּ עִמָּהּ וַיֹּאכַל.

Gen 3:6 When the woman saw that the tree was good for eating and a delight to the eyes, and that the tree was desirable as a source of wisdom, she took of its fruit and ate. She also gave some to her husband, and he ate.

The Torah never identifies the fruit, but subsequent biblical interpreters could not resist the temptation to give it a name. Surprisingly, the apple does not appear on the scene for centuries.

Midrashic Interpretations

Genesis Rabbah 15:7, from the mid-1st millennium C.E., highlights the rich and variegated rabbinic discourse surrounding the identity of the forbidden fruit, listing as possible candidates wheat, grapes, citrons, and figs. The fate of these varied greatly.

Wheat leaves almost no trace.[2]

The citron fares a little better. According to Rivka Ben-Sasson, “during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, the citron was described by the crusaders as ‘Adam’s Apple,’ due [to] the narrowing on the upper part of some of the citron fruits that can resemble the bite of a human being.”[3] And the citron is unmistakable in Jan van Eyck’s Ghent Altarpiece, which was completed in 1432.[4]

Grapes, on the other hand, enjoyed widespread popularity. They are championed as early as the Book of Enoch (250–200 B.C.E.), which describes a vision of a composite tree, whose fruit is like vine clusters:

1 Enoch 32:4 That tree is in height like the fir, and its leaves are like (those of) the Carob tree: and its fruit 32:5 is like the clusters of the vine, very beautiful: and the fragrance of the tree penetrates afar.

Other apocalyptic writings from the early 1st millennium C.E., such as the Greek Apocalypse of Baruch and the Apocalypse of Abraham, take a similar approach.[5]

The grape tradition also enjoyed great prominence among Christian commentators. The third-century scholar Origen of Alexandria, commenting on the vineyard Noah planted after the floodwaters ebbed, declares: “[This] was the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil.”[6] The importance of the fig is affirmed nearly a millennium later, when the 12th century Bible scholar Andrew of St. Victor identified the grape as commonly associated with the Fall of Man. Aside from the fig, the grape is the most widely identified forbidden fruit, prior to the rise of the apple. Though never stated explicitly, the identification of the forbidden fruit with the grape is likely driven by the association of wine with sin.

The final candidate in Genesis Rabbah, the fig, was the most popular choice in later interpretations, presumably because its connection to the forbidden fruit is anchored in the biblical narrative. Immediately after eating the fruit, Adam and Eve realize they are naked and cover themselves with fig-leaf garments:

בראשׁית ג:ז וַתִּפָּקַחְנָה עֵינֵי שְׁנֵיהֶם וַיֵּדְעוּ כִּי עֵירֻמִּם הֵם וַיִּתְפְּרוּ עֲלֵה תְאֵנָה וַיַּעֲשׂוּ לָהֶם חֲגֹרֹת.

Gen 3:7 Then the eyes of both of them were opened and they perceived that they were naked; and they sewed together fig leaves and made themselves garments.

If Adam and Eve were standing by the fig tree when they sinned, the argument goes, this was likely the tree whose fruit they consumed. Fig trees appear in wide range of textual and visual sources, including the immensely popular Life of Adam and Eve (early 1st millennium C.E.), an apocryphal account of Adam and Eve’s lives after the expulsion from Eden, copies of which survive in Greek, Latin, Armenian, Georgian, Slavonic, and the Western European vernaculars.[7]

Many prominent Christian authors either implied or outright asserted that the forbidden fruit was a fig, including Augustine, Theodore and Hadrian, two of the earliest Bible scholars in England, Alcuin of York (d. 804), one of the leading scholars of the Carolingian court, and Thomas Aquinas.[8]

The Forbidden Fruit in Art

The artistic depiction of the forbidden fruit is, up to a certain point, congruent with the textual sources. The fig and grape are dominant, with occasional representations of other fruit varieties.

To get a sense of the richness of the iconographic tradition, imagine an early 13th century Benedictine monk from the Church of St. Pierre in Aulnay de Saintonge in Western France who undertakes a pilgrimage to Rome, with a visit to Amiens, north of Paris, to see the great cathedral under construction there. His first stop is at Airvault, just north of Aulnay. He is, of course, familiar with the forbidden fruit on the capital of his own church, an indeterminate round fruit, so he notes with interest that at Airvault the tree is a fig. When he reaches Amiens he is struck that the fruit is a grape.

From Amiens he proceeds south to the Abbey of St. Denis in the northern suburbs of Paris, where the serpent holds a cluster of grapes in its mouth. Grapes recur at the Abbey of Sainte-Madeleine in Vézelay, along with a second Fall of Man scene in which Eve offers Adam a pomegranate. The famed Cluny Abbey, a week’s journey to the south, again has grape clusters, while the church of the nearby town of Neuilly en Donjon depicts Adam and Eve standing together between two identical trees that lack botanical characteristics.

Less than a hundred miles away, a fresco in the church at Saint Jean des Vignes depicts the serpent passing to Eve a small black fruit, apparently an olive. The pomegranate appears again in the church at St. Paul de Varax, North of Lyon, while the priest’s last two stops before crossing into Italy belong to the fig tradition: a church at Tarascon, and the Cathedral (now Church) of St. Trophime in Arles.

|

|

|

Grapes - Anonymous, 1120-1132. France, Vézelay, Basilique Sainte Madeleine, Nave Capital. Credit: Jean Marie Sicard |

Pomegranate- Anonymous, 1000-1135. France, Vézelay, Basilique Sainte Madeleine, Capital 93. Credit: Jean Marie Sicard |

The Apple Enters the Scene

The decisive break in the artistic renditions of the Eden story appears in France, in the early 12th century. In addition to the species listed above, a keen observer would recognize a tentative newcomer: the apple. An illustrated psalter from the Church of St. Fuscien in northern France (1180–90) shows Adam about to eat a round fruit with what appears to be an apple stem, and the forbidden fruit on the capital at the south side of the St. Pierre Cathedral in Airvault displays the distinctive cleft (stamen) of the apple.

|

|

| Apple- Anonymous, 1100-1200. France, Airvault, Saint Pierre Church. Credit: Béatrice Delepine, 2014 |

Apple - Anonymous, 1250-1299. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Arsenal 3516, fol. 4r. |

The evolution of the apple to become the dominant forbidden fruit occurs quite suddenly and across varous artistic media, with apples appearing on stained glass windows, in illuminated manuscripts, church reliefs, and more.

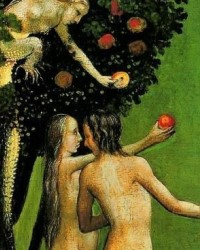

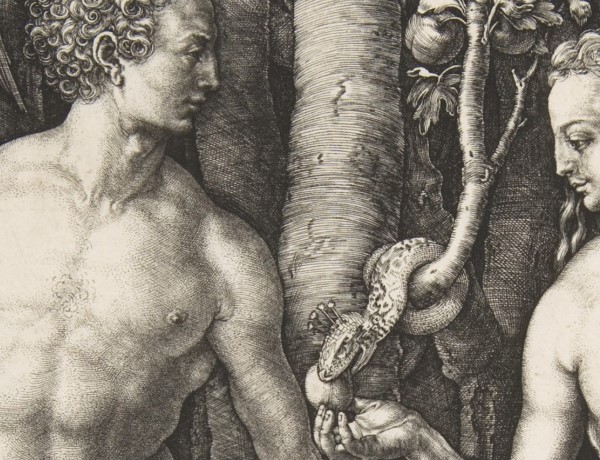

The shift soon extends beyond France, though the transformation occurs more gradually. By the middle of the 13th century, apples begin to populate the English iconographic landscape, largely displacing figs by the early 14th century. In Germany, too, scenes of Adam and Eve from the 10th to the 12th centuries display a familiar mix of figs, pomegranates, and other fruit, but these begin to give way to the apple in the 13th century, an artistic traditioin culminating in the works of the northern masters such as Hugo van der Goes, Hieronymus Bosch, Lucas Cranach the Elder, and Albrecht Dürer.

|

|

|

Apple - Adam and Eve, Albrecht Dürer, 1507. Madrid, Museo del Prado. Wikimedia |

Apple - Adam and Eve Albrecht Dürer, 1507. Met Museum |

However, the apple’s dominance was not universal. Italy, for example, did not adopt the apple iconography at this time. The fig maintained its primacy during well into the 16th century.

A Popular but Incorrect Hypothesis

How then did the apple, virtually undocumented until well into the 2nd millennium C.E., become the de facto forbidden fruit? And why did other fruits commonly identified as the forbidden fruit lose that association?

In Vulgar Errors, a book dedicated to the refutation of hundreds of views held as truths, Sir Thomas Browne, the great 17th century English polymath, offers the explanation for the rise of the apple that has been standard since his time: it derives from the two meanings of the Latin word malum: “apple” and “evil.”[9] The hypothesis has great intuitive appeal.

The Christian interpretive tradition understands Adam and Eve’s transgression as the source of “original sin” with all the resulting evils, including expulsion from the Garden of Eden and the introduction of death into the world.[10] Theologically, this was a terrible malum, “evil”—what fruit, then, is more likely to have played a part in it than the malum, “apple”?

Still, the hypothesis is flawed. The word play on malum is hardly found in the Latin commentary tradition to Genesis, which prefers two general terms for fruit: fructus or, by far the most popular term, pomum, “fruit” or “orchard fruit.”[11] Remarkably, even when they discuss the malum, “evil,” of Eve’s transgression, that is, in the passages where we would most expect an allusion to the second meaning of malum, i.e., “apple,” Latin writers still refer to the forbidden fruit as a pomum.[12]

The Fruit Becomes an Apple

If the play on the Latin malum is not the source of the identification of the forbidden fruit as an apple, what is? To understand the rise of the apple we must focus on two historical developments. One is linguistic, the other artistic. As noted above, pomum (“fruit” or “orchard fruit”) was the most common Latin word for the forbidden fruit. In Old French, which descends from Latin, pomum became pom. Old French translations of the Latin Vulgate thus use pom as an equivalent both of Latin pomum and of other Latin words for “fruit.”

But language is not static, and over time the meanings of words tend to change, and this is precisely what occurred here. By a process known as “semantic narrowing,” the word pom gradually took on the more restricted sense “apple.”[13] As a result, there developed a break between the meaning intended by the authors and the meaning understood by later readers. While the authors were referring to the forbidden fruit, after the change in the meaning of pom, readers understood these texts to refer to a forbidden apple.

Such references were common. From a 12th-century translation of Genesis, through Old French retellings of the biblical narrative and the poetry of Marie de France (the earliest known female poet of Old French), to the the 12th century play Jeu d’Adam, all refer to a forbidden pom.[14] The “forbidden pom” even finds its way into nonbiblical works such as Le roman de Renart, a satirical French poem, and the first French adaptation of Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

These (and many other) Old French accounts of the Fall of Man communicated a clear and simple lesson: Adam and Eve were tempted by an apple. Once this lesson was learned, the apple was first introduced and then came to dominate the forbidden fruit iconography of France.

England and Germany

A similar linguistic process occurs in England and Germany, though not as quickly or completely. In part due to the cultural influence of French, Middle English appel and Middle High German apfel undergo a semantic narrowing, and, like pom, their meaning shifts from “fruit” to “apple,” eventually establishing the apple as the forbidden fruit throughout northern Europe by the second half of the 13th century.

Italy

The Italian word for “apple,” mela (a descendent of Latin malum), however, never meant “fruit,” and so did not denote the forbidden fruit at any point. This explains why the rise of the apple in the Italian iconographic record is tentative and later than that identification in France, Italy, and Germany: a single apple in the 13th century, and a scattering in the 14th and 15th.

The fig, in contrast, continues to bloom, enjoying the same level of dominance in the 14th and 15th centuries as the apple does in France. In the early 16th century, the fig appears in some of the best-known Renaissance masterpieces, including Albertinelli’s Creation and Fall of Man, the Stanze di Raffaello and the Loggia di Raffaello in the Vatican, and in the best-known Fall of Man scene of all, Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel.

It is not until the middle of the 16th century, centuries after the apple was securely established in other parts of Europe, that it became a fixture of Italian iconography, e.g., in Giulio Clovio’s Farnese Hours and canvases by Tintoretto and Titian. At that point, all the major artistic centers of Europe belonged to the apple camp.

Over time, the narrow sense of pomme, apple, and Apfel (as these words came to be spelled) became the only sense, anachronistically transforming earlier forms into unwitting witnesses to the apple tradition.

The Apple is Canonized by the Printing Press

The apple also received outside help from Johannes Guttenberg and the inestimable cultural impact of the printing press. In the early 16th century, the world’s major publishing houses were located in northern Europe and leading Northern artists such as Albrecht Dürer, Albrecht Altdorfer, and Lucas Cranach, were active in this field—all champions of the apple tradition.

Not surprisingly, when the 1550 edition of Martin Luther’s Bible translation incorporated the first “Fall of Man” scene, it was an apple-tradition woodcut by Hans Brosamer. Here, the apple tradition had been severed from its linguistic roots, and the revolutionary new medium of print disseminated forbidden apples to the farthest reaches of Europe and beyond.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

October 20, 2022

|

Last Updated

March 25, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Azzan Yadin-Israel is Associate Professor of Jewish Studies in the departments of Classics and Jewish Studies at Rutgers University. He holds a Ph.D. from University of Califronia, Berkeley and Graduate Theologial Union. He is the author of Scripture as Logos: Rabbi Ishmael and the Origins of Midrash and Scripture and Tradition:Rabbi Akiva and the Triumph of Midrash.

Essays on Related Topics: