Edit article

Edit articleSeries

The Angel YHWH Visits Abraham: Rashbam Reworks a Christian Interpretation

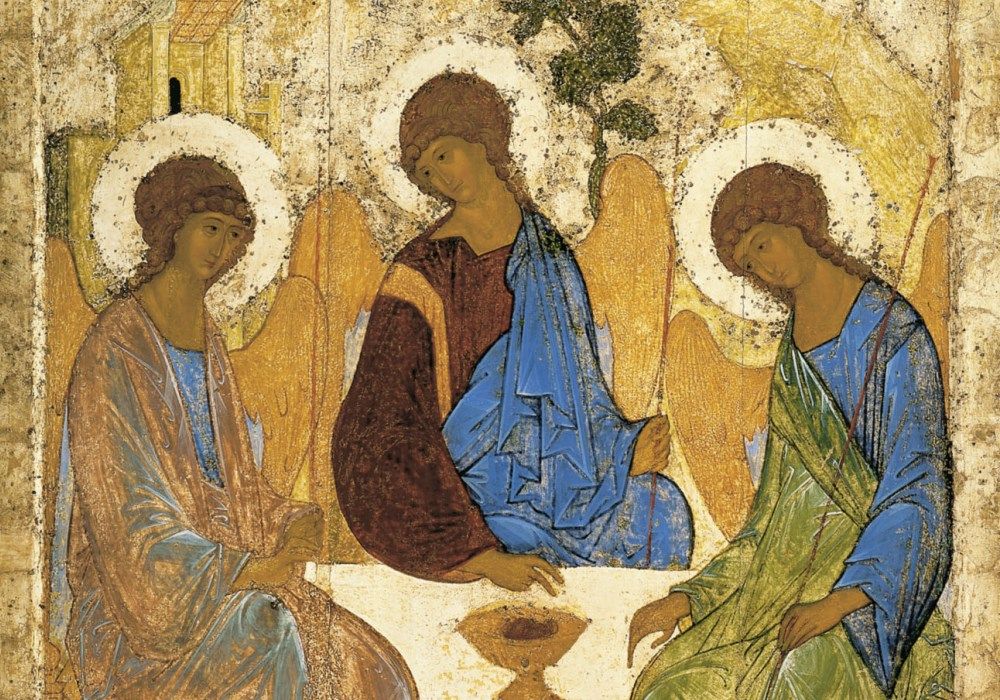

The Trinity, three angels hosted by Abraham at Mamre, by Andrei Rublev, ca. 1425–27. Wikimedia

Abraham is sitting outside his tent when YHWH appears to him:

בראשית יח:א וַיֵּרָא אֵלָיו י־הוה בְּאֵלֹנֵי מַמְרֵא וְהוּא יֹשֵׁב פֶּתַח הָאֹהֶל כְּחֹם הַיּוֹם.

Gen 18:1 YHWH appeared to him [Abraham] by the terebinths of Mamre; he was sitting at the entrance of the tent as the day grew hot.

Instead of hearing more about the appearance of YHWH, we are told in the next verses that Abraham sees three visitors standing before him:

בראשית יח:ב וַיִּשָּׂא עֵינָיו וַיַּרְא וְהִנֵּה שְׁלֹשָׁה אֲנָשִׁים נִצָּבִים עָלָיו וַיַּרְא וַיָּרָץ לִקְרָאתָם מִפֶּתַח הָאֹהֶל...

Gen 18:2 Looking up, he saw three men standing near him. As soon as he saw them, he ran from the entrance of the tent to greet them...

What is the relationship between YHWH’s appearance and the three visitors? Traditional exegesis falls into two camps:

YHWH Sent Three Visitors—God “appeared” to Abraham by sending three men/angels. For example, Solomon Dubno (1738–1813) in his commentary on Genesis,[1] explains:

נתיבות שלום באור בראשית יח:א ...בפסוק ראשון הוא מזכיר דרך כלל שנראה אליו ה', ואח[רי] ז[ה] מפרש האיך, ואמר שראה שלשה אנשים שהיו מלאכים...

Netivot Shalom Beʾur Gen 18:1 …The first verse mentions in general that Hashem (“the name” = YHWH) appeared to him, and afterwards it explains how, and it said that he saw three men that were angels…[2]

At this point in the chapter, this interpretation seems to be the peshat (simpler, more contextually appropriate meaning).[3]

God Plus Three Visitors—According to this understanding, first God appears to Abraham (v. 1), and then, in a separate event, three men/angels visit Abraham (v. 2). Thus, R. Menachem b. Solomon (12th cent. Italy) writes in his Sekhel Tov:

שכל טוב בראשית יח:ב "וישא עיניו וירא"—לאחר שנגלה עליו שכינה.

Sekhel Tov Gen 18:2 “And he lifted his eyes, and he saw”—after the divine presence appeared to him.

This would mean that Abraham has a total of four visitors. This may seem farfetched at first, but as the story goes on, sometimes Abraham seems to be speaking to one person and sometimes to a group.

Speaking to One Person or a Group?

In the next verse (v. 3), Abraham addresses the visitor(s) as אֲדֹנָי (adonai), the plural form of “lord,” which, as the Talmud notes, can apply either to the group of men or to God,[4] for whom this term is always used in plural as a sign of distance and respect:

בבלי שבועות לה: [כת"י פירנצה 8–9] כל השמות האמורים באברהם קודש[5] חוץ מזה שהוא חול: "ויאמר אדני[6] אם נא מצאתי חן בעיניך."

b. Shevuot 35b [MS Florence 8–9] Every term [that can be used as a divine epithet] used in the Abraham narrative is holy (i.e., it refers to God) except for one which is secular (Gen 18:3): “He said: ‘Adonay, if it please you.’”

חנינה בן אחי ר' יהוש[ע] ור' אלעז[ר] בן עזריה אמרו משום ר' אלעז[ר] המודעי: "אף זה קודש."

Hananiah son of R. Joshua’s brother, and R. Elazar son of Azariah said, quoting R. Elazar of Modiʿin: “This too is holy (i.e., refers to God).”[7]

The Talmud explicates the position that Adonai here refers to God by noting that Abraham and Sarah prioritized the three travelers over YHWH himself:

כמאן אזלא הא דא[ר] רב יהוד[ה]: "גדולת הכנסת אורחים מהקבלת פני שכינה"? כמאן? כאותו הזוג.

Whose opinion does Rav Judah follow when he says, “Taking care of guests is greater than receiving the Divine Presence”? Whose? That very pair (= Hananiah son of R. Joshua’s brother, and R. Elazar son of Azariah).

In the Masoretic text, Abraham seems to be addressing either God, or just the leader of the visitors, since he uses the singular:

בראשית יח:א וַיֹּאמַר אֲדֹנָי אִם נָא מָצָאתִי חֵן בְּעֵינֶיךָ אַל נָא תַעֲבֹר מֵעַל עַבְדֶּךָ.

Gen 18:3 He [Abraham] said: “Adonay, if I have found favor in your (singular) eyes, do not go (singular) on past your (singular) servant.”

Indeed, when we look at the ancient versions, we can see that the Greek Septuagint (LXX) and the Syriac Peshitta read the ambiguous word אדני as “my lord,” in the singular.[8] In contrast, the Samaritan Pentateuch has the whole text in the plural:

בראשית יח:ג [נוסח שומרון] ויאמר אדני אם נא מצאתי חן בעיניכם אל נא תעברו מעל עבדכם׃

Gen 18:3 [SP] He [Abraham] said: “My lords, if I have found favor in your (plural) eyes, do not go (plural) on past your (plural) servant.”

In the next two verses, Abraham continues his speech only in the plural in all versions, so he is definitely speaking now to the three visitors:

בראשית יח:ד יֻקַּח נָא מְעַט מַיִם וְרַחֲצוּ רַגְלֵיכֶם וְהִשָּׁעֲנוּ תַּחַת הָעֵץ. יח:ה וְאֶקְחָה פַת לֶחֶם וְסַעֲדוּ לִבְּכֶם אַחַר תַּעֲבֹרוּ כִּי עַל כֵּן עֲבַרְתֶּם עַל עַבְדְּכֶם...

Gen 18:4 Let a little water be brought; bathe your (plural) feet and recline (plural) under the tree. 18:5 And let me fetch a morsel of bread that you (plural) may refresh yourselves (plural); then go (plural) on—seeing that you have come (plural) your (plural) servant’s way.”

The response to Abraham in all texts is in the plural, meaning it comes from the men:

בראשית יח:ה ...וַיֹּאמְרוּ כֵּן תַּעֲשֶׂה כַּאֲשֶׁר דִּבַּרְתָּ.

Gen 18:5 They replied, “Do as you have said.”[9]

To make sense of Abraham’s speech, we have to say either that Abraham in v. 3 is addressing the head man/angel, and, having secured his agreement,[10] he addresses the whole group (vv. 4–5), or that first Abraham addresses God and asks Him to wait (v. 3), and then he turns his attention to the three men/angels (vv. 4–5). This latter interpretation, based on the Talmudic passage quoted above, is found in Rashi:

רש"י בראשית יח:ג ...והיה אומר להקב"ה להמתין לו עד שירוץ ויכניס את האורחים.

Rashi Gen 18:3 …He was telling the Blessed Holy One to wait for him while he ran and tended to the guests.

YHWH Appears in the Story Again

After the visitors have their meal, they ask where Sarah is, and Abraham responds that she is in the tent. At this point, one of the visitors speaks:

בראשית יח:י וַיֹּאמֶר שׁוֹב אָשׁוּב אֵלֶיךָ כָּעֵת חַיָּה וְהִנֵּה בֵן לְשָׂרָה אִשְׁתֶּךָ...

Gen 18:10 Then he said, “I will return to you next year, and your wife Sarah shall have a son!”…

Sarah overhears and laughs, and suddenly YHWH speaks:

בראשית יח:יג וַיֹּאמֶר יְ־הוָה אֶל אַבְרָהָם לָמָּה זֶּה צָחֲקָה שָׂרָה לֵאמֹר הַאַף אֻמְנָם אֵלֵד וַאֲנִי זָקַנְתִּי.

Gen 18:13 Then YHWH said to Abraham, “Why did Sarah laugh, saying, ‘Shall I in truth bear a child, old as I am?’”

YHWH Refers to Himself in the Third Person?

As this speech continues, YHWH, the speaker, starts referring to YHWH in the third person:

בראשית יח:יד הֲיִפָּלֵא מֵיְ־הוָה דָּבָר לַמּוֹעֵד אָשׁוּב אֵלֶיךָ כָּעֵת חַיָּה וּלְשָׂרָה בֵן.

Gen 18:14 “Is anything too wondrous for YHWH? I will return to you at the same season next year, and Sarah shall have a son.”[11]

This is an atypical way for God, or people, to refer to themselves.[12]

An Angel Named YHWH: Rashbam

Rashbam, Rabbi Samuel ben Meir (c. 1080–c. 1160), Rashi’s grandson, was perhaps the medieval Jewish Bible commentator with the strongest commitment to peshat, the plain or contextual meaning of the Torah text. His solution here to both problems is that the YHWH in this story is not God but the name of the leader of the three visitors![13]

רשב"ם בראשית יח:יג "ויאמר י״י"—המלאך, גדול שבהם.

Rashbam Gen 18:13 “YHWH said”—the chief angel.

He reiterates this in his commentary to the verse describing how the visitors left Abraham and headed to Sodom:

רשב"ם בראשית יח:טז "ויקמו משם האנשים"—שנים מהם הלכו לסדום, כדכתיב: ויבאו שני המלאכים סדומה וגדול שבהם היה מדבר עם אברהם.

Rashbam Gen 18:16 “The men set out from there”—Two of them went to Sodom, as it is written (19.1), “The two angels arrived in Sodom,” while the chief angel remained speaking with Abraham (v. 17).

וזהו שכתוב בו: וי״י אמר המכסה אני וגו ואברהם עודנו עומד לפני י״י שני פסוקים אלו מדברים [ב]שלישי.[14]

About this [chief angel] it is written (v. 17), “Now YHWH [i.e. the chief angel] said, ‘Shall I hide’,” and (v. 22), “Abraham remained standing before YHWH [i.e. the chief angel].” Both these verses refer to the third [angel].

In the medieval “Oxford-Munich collection,”[15] that is apparently based on Rashbam’s interpretation (without naming him), the point is made even more clearly:

אוקספורד מינכן בראשית יח:כ המלאך ששמו ה' אמר לאברהם

Oxford-Munich Gen 18:20 The angel who was named YHWH said to Abraham.[16]

As YHWH is also the name of God, whenever YHWH speaks about YHWH in third person in this story, Rashbam understands it as the chief messenger speaking about God. But he understands any mention of YHWH by the narrator as a reference to the chief messenger. Thus, when Abraham argues with YHWH about the fate of Sodom, he is arguing not with God but with the chief messenger/angel.[17]

Christian Interpretation: The Lord in the Story Is Jesus

Rashbam’s interpretation is surprisingly similar to certain Christian explanations. The earliest example comes from the Church Father, Justin Martyr (c. 100 – c. 165 C.E.), in his Greek Dialogue with Trypho—Trypho is the Jew with whom Justin is debating—who explains that the chief angel is God, but not God the father, who remains eternally in heaven and never manifests on earth. Rather, the chief visitor is God the son (i.e., Jesus), in an earlier incarnation:

Justin, Dialogue with Trypho §56.1 Moses,[18] then, that faithful and blessed servant of God, tells us that he who appeared to Abraham under the oak tree of Mamre was God, sent, with two accompanying angels, to judge Sodom by another, who forever abides in the super-celestial regions, who has never been seen by any man, and with whom no man has ever conversed, and whom we call Creator of all and Father.[19]

A few years after Justin, the Church Father Tertullian (c. 155 – c. 220), writing in Latin, explained that in chapters 18 and 19, the “Lord” here on earth, whom he identifies explicitly as Jesus, makes reference to the “Lord” in heaven.[20] Tertullian addresses and stridently criticizes Jews for refusing to acknowledge that this is what the text means:

Tertullian, Against Praxeas §1 A much more ancient testimony [of Jesus’ divinity] we have also in Genesis: “Then the Lord [= Jesus] rained upon Sodom and upon Gomorrah brimstone and fire from the Lord out of heaven.” Now, either deny that this is Scripture; or else (let me ask) what sort of person are you...”[21]

Justin and Tertullian’s interpretation of Lord as Jesus appearing on earth to represent God the father, who remains in heaven, is only one Christological understanding of Genesis 18. Some Christian interpreters emphasize here proof of the incarnation, since YHWH appears with a body in the story; other Christians saw proof of the Trinity. They even had a common Latin phrase about the events of Genesis 18: “tres vidit et unum adoravit,” meaning “He [Abraham] saw three but worshipped only one.” David Berger of Yeshiva University’s Bernard Revel Graduate School of Jewish Studies wrote that this line was so popular that it “attained the status of Scriptural or quasi-Scriptural quotation in the minds of many Christians.” Some Jews even thought that the line was in the New Testament.[22]

Rabbi Abraham ibn Ezra (1089–1164), Rashbam’s younger contemporary who moved from Muslim Spain to Christendom later in life, confronts the trinity interpretation in his opening comment on the story:

אבן עזרא יח:א תועי רוח אמרו: כי השם – שלשה אנשים, והוא אחד, והוא שלשה, ולא יתפרדו. והנה שכחו (בראשית יט:א) "ויבאו שני המלאכים סדומה."

Ibn Ezra Gen 18:1 Those who stray spiritually say that God is the three men. He is one and He is three and they are inseparable. But they forget (Gen 19:1) “and the two angels arrived in Sodom.”

In other words, ibn Ezra implies, this cannot refer to the inseparable trinity since one is indeed separated off in the next part of the story.

Rashbam obviously did not accept the theology of the Church Fathers when he wrote that Genesis 18 describes both a YHWH on earth and another YHWH in heaven. But as far as I know, Rashbam is the first rabbinic Jew to offer an interpretation so strikingly similar to this common Christian one.[23] But how likely would it be for Rashbam to offer a novel interpretation of a biblical passage which closely resembles a Christian one?

Response to Christian Exegesis in Rashi, Rashbam, and Bekhor Shor

In medieval Jewish Bible commentaries, some comments must be understood as polemics against Christianity and/or Christian Bible exegesis, sometimes even when those comments are not labeled as such. The extent of polemical comments in any given commentator has been debated.

For example, while Shaye Cohen of Harvard University argues that Rashi’s Torah commentary does not include any direct engagement with Christianity or with Christian Bible exegesis,[24] Elazar Touitou (1929–2010) of Bar Ilan University and Avraham Grossman (1936–2024) of Hebrew University claim that anti-Christian polemics were a crucial motivating factor in Rashi’s oeuvres, including in his Torah commentary.[25] One example they and others point to is Rashi’s negative depiction of Esau, which they see as using code to belittle Christians or Christianity. According to Rashi, Esau will always be a blood shedder; Esau entraps and deceives with insincere speech; Esau’s very name implies hatred.[26]

David Berger summed up the modern scholarly debates:

In matters of exegetical detail, polemical motives are occasionally obvious, occasionally likely, and occasionally asserted implausibly.[27]

Whether Rashi’s Torah commentary engages with Christianity or not is debatable, but the Torah commentaries of Rashbam and his younger contemporary, Rabbi Joseph Bekhor Shor, who also lived in Northern France, and like Rashbam, took interest in peshat,[28] definitely do.

Bekhor Shor’s Polemic

Bekhor Shor’s disdain for Christians is often obvious. For example, in his comment on God’s speech to Miriam and Aaron on the uniqueness of Moses’ prophecy he writes:

בכור שור במדבר יב:ז–ח ובכאן נשברו זרועם של אומות העולם שאומרים על מה שאמר משה רבינו: אלגוריא הם, כלומר: חידה ומשל. ואינו מה שהוא אומר, ומהפכין הנבואה לדבר אחר, ומוציאין הדבר ממשמעותו לגמרי...

Bekhor Shor 12:7–8 Here we find convincing proof against the position of the gentiles [literally: “here the gentiles’ arms are broken”] who claim that everything that Moses said was allegoria, i.e. a riddle and a parable, and is not to be understood literally. They thus understand [Moses’] prophecies as something utterly different, and remove the text totally from its [real] meaning....

שאף על פי שהעתיקו את התורה מלשון הקודש ללשונם, לא נתן להם הקב״ה לב לדעת ועינים לראות ואזנים לשמוע... כי אין רוצה וחפץ בהם שידבקו בתורתו.

Even though they translated the Torah from Hebrew into their own language, God did not give them “a mind to understand or eyes to see or ears to hear” (Deut 29:3)... since God does not want them to be connected to the Torah.[29]

But Rashbam’s commentary is different. While it contains comments that specifically and explicitly argue with Christians or Christian exegesis and comments that, it is likely, implicitly argue,[30] Rashbam isn’t entirely negative in his treatment of Christian exegetes, as is evident by his tone and attitude.

Rashbam’s Depiction of Non-Israelite Characters

Deviating surprisingly from the thrust of earlier Jewish Bible interpretation, Rashbam’s comments about Esau and Balaam, the two characters in the Torah that are often seen in Jewish typology as representing Christianity or Jesus, refrain from hinting at something negative about Christians, but instead depict them simply as characters with good and bad characteristics.

When Esau and Jacob meet again after twenty years, Rashbam states that Jacob’s fear was unwarranted since he failed to recognize that Esau was approaching him in a friendly manner, full of brotherly love, as reported back to Jacob by his messengers:

רשב"ם בראשית לב:ז "וגם הנה הוא" מתוך ששמח בביאתך ובאהבתו אותך, "הולך לקראתך וארבע מאות איש עמו"—לכבודך, זהו עיקר פשוטו.

Rashbam Gen 32:7 “And he himself” due to his happiness at your coming and due to his love for you, “is coming to greet you and there are four hundred men with him”—to honor you. This is the true meaning according to the plain sense of Scripture.

When it comes to Balaam, Rashbam describes how the gentile prophet learned from his errors and was rewarded:

רשב"ם במדבר כד:א ...אלא מעתה נתכוון לברכם בלב שלם. ומתוך כך כת': "ותהי עליו רוח אלהים"—כאן, שרוח שכינה שרתה עליו מאהבה ודרך חיבה.

Rashbam Num 24:1 … Rather, from this point on he intended to bless them with all his heart. And for this reason, it is written here that “the spirit of God came upon him”—i.e., the spirit of the Divine Presence came upon him with love and with affection.[31]

Conversations with Christians

Rashbam is the only one of these three commentators who explicitly reports on conversations he had with Christians about the meaning of biblical verses. He has no doubt that his own interpretations are superior. For example, he writes that they admitted that he was right and that their Latin books were inaccurate:

רשב"ם שמות כ:יב "לא תרצח"—כל רציחה, הריגה בחינם היא בכל מקום... תשובה למינים והודו לי. ואף על פי שיש בספריהם: "אני אמית ואחיה" (דברים לב:לט), בלשון לטין של "לא תרצח", הם לא דיקדקו.

Rashbam Exod 20:12 “You shall not murder”—The verb ר.צ.ח always – wherever it appears – refers to unjustified homicide…. I offered this explanation as an argument against the Christians [literally “sectarians”] and they admitted that I was right. Even though in their Latin books the same verb (occidere, “to kill”) is used to translate the verb מ.ו.ת in the phrase (Deut 32:39) “I deal death (אמית) and I give life [ego occidam et ego vivere faciam],” and the verb ר.צ.ח in this verse [non occides], their translators are inaccurate.[32]

Similarly, Rashbam reports that he explained to them the principle behind the law of not mixing linen and wool (see Lev 19:19; Deut 22:11) and they accepted his explanation:

רשב"ם ויקרא יט:יט ולמינים אמרתי: הצמר צבוע והפשתן איננו צבוע, וקפיד בבגד של שני מראות, והודו לי.

Rashbam Lev 19:19 To the Christians I said that the text outlawed clothing of two different colors, for wool is [generally] colored, but linen is not. They accepted this explanation.

In these reports, Rashbam expresses no disdain toward them.

“Shiloh”—Christians and Rabbis Are Both Wrong

Rashbam offers a novel interpretation of Jacob’s reference to Shiloh in his blessing of Judah, a verse that was often argued about by Jews and Christians. In so doing, he explicitly rejects the Christian reading that understands Shiloh as a reference to Jesus “the messenger,” but at the same time and in the same tone he also rejects a common Jewish interpretation, reading the name as the possessive pronoun she-lo:

רשב"ם בראשית מט:י ופשט זה תשובה למינין, שאין כתוב כי אם שילה שם העיר... לא ״שלו״ כתוב כאן כדברי העברים, ולא ״שליח״ כדברי הנוצרים.

Rashbam Gen 49:10 This interpretation constitutes a refutation of the explanation of the Christians. “Shiloh,” which is written here, is just the name of a city.... Neither is she-lo (“his”) written here, as [some] Jews claim,[33] nor shaliaḥ (“a messenger”) as [some] Christians say.[34]

In sum, Rashbam’s Torah commentary reflects a more positive attitude to non-Jews than Rashi’s or Bekhor Shor’s do.[35]

Andrew of St. Victor Learned from Rashbam: Evidence from the Christian Side

In her important book In Hebreo,[36] Montse Leyra Curia of Madrid’s San Dámaso University notes that Rashbam’s slightly younger Christian contemporary, Andrew of St. Victor (d. 1175), quotes Jewish interpretations of the Bible frequently and without rancor. She argues, convincingly in my opinion, that Andrew did not have the text skills to read medieval Hebrew. What he knew about Jewish biblical exegesis—and he knew a lot—was from conversations with Jews.

Leyra counts up the number of times where the interpretation that Andrew writes in the name of the Iudaei or Hebraei, the Jews, is the same as Rashi’s, ibn Ezra’s, or Rashbam’s. She concludes that Andrew’s largest source of Jewish exegesis of the Torah was Rashbam’s commentary which he must have learned from conversations either with Rashbam or with a student of his.[37] This supports the implications from Rashbam’s own commentary, that he discussed the Bible with Christians, and that the discussions were not necessarily confrontational.[38]

Similarly, Rashbam’s younger brother, Rabbi Jacob (Rabbeinu Tam, ca. 1100–1171), also had cordial discussions with Christians about the Bible, as recently shown by Yosaif Dubovick of Herzog College and Avraham Reiner of Ben Gurion University.[39] While Rashbam certainly rejected the Christological implications of his novel interpretation of Genesis 18, its similarity to a common Christian understanding shows that he could learn and assimilate Christian insights into his commentary in a Jewish way.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

November 14, 2024

|

Last Updated

December 27, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Rabbi Marty Lockshin is Professor Emeritus at York University and lives in Jerusalem. He received his Ph.D. in Near Eastern and Judaic Studies from Brandeis University and his rabbinic ordination in Israel while studying in Yeshivat Merkaz HaRav Kook. Among Lockshin’s publications is his four-volume translation and annotation of Rashbam’s commentary on the Torah.

Essays on Related Topics: