Edit article

Edit articleSeries

The Law of the Goring Ox: Is It Neutered?

Jüdischer Viehhändler. Signiert. Gouache. 1909

The Most Celebrated Animal in Legal History

In the village life of ancient Israel and the ANE, it was probably not a rare event that large cattle would gore people. The Torah has a set of laws dealing with this circumstance, as do the 18th century B.C.E. Babylonian law collections, the Laws of Eshnunna (53-55) and the Laws of Hammurabi (250-252), and also the Mishna (Bava Qama, chs. 1-5) and accompanying rabbinic literature (Tosefta, Talmud, etc.), which discuss and expand the Torah’s precedent. Bernard Jackson, a leading scholar of ancient Near Eastern law, calls the “goring ox” of Exodus 21 “the most celebrated animal in legal history” because of the large corpus of scholarly literature generated by the topic.[1]

The Torah distinguishes between an animal that gores unexpectedly and an animal that is a habitual gorer (biblical שור נגח, in rabbinic parlance: שור מועד).

שמות כא:כח וְכִי יִגַּח שׁוֹר אֶת אִישׁ אוֹ אֶת אִשָּׁה וָמֵת…

Exod 21:28 When a shor gores a man or a woman to death…

כא:כט וְאִם שׁוֹר נַגָּח הוּא מִתְּמֹל שִׁלְשֹׁם וְהוּעַד בִּבְעָלָיו וְלֹא יִשְׁמְרֶנּוּ…

21:29 If, however, that shor has been in the habit of goring, and its owner, though warned, has failed to guard it…

In the former case, the owner loses his animal, a very valuable possession. This may be less of a punishment however, and more of a way to allow the community to vent their rage at the animal who killed one of their own and to act as “corporate executioner by engaging in controlled mob violence.”[2] (Stoning is not exactly the most efficient way to dispatch an animal that weighs as much as 1,500 pounds.) As harsh as this may sound, it stands in stark contrast to what happens to the owner of a “habitual gorer” in v.29 who may forfeit his very life because of his negligence, depending on whether the victim was a free person (death penalty or unspecified “ransom” payment, depending on the wishes of the victim’s family) or a slave (stiff fine).

The ANE law collections have more or less the same division, but with different penalties. Two differences that stand out are that in the Torah, the offending animal is killed and if the animal is a habitual gorer, the owner is killed as well. The Babylonian codes never kill the ox or the owner. The difference is grounded in the gravity with which the Torah views homicide: according to Numbers 35:33, killing a person pollutes the land with bloodshed and so endangers those who reside there unless the murderer is executed. This holds true even when the culpable party is not human (Genesis 9:5).[3]

Translation of Shor: Ox or Bull?

Zooarcheologists, those who study ancient animal remains, note that the domestication of large cattle in the Near East began before 5000 B.C.E. Large cattle were valuable for many reasons: their dung (used as fertilizer and fuel), their meat, hide, and bone. Cows were valuable for their milk, which, although less popular than goat’s milk in biblical society,[4] was easier to use for the production of butter and cream.

Perhaps their greatest value for farmers was as draft animals. Oxen, i.e. gelded (castrated) bulls, have been used for plowing beginning already in the fourth millennium B.C.E.[5] The use of both cows and oxen as working animals was also commonplace in Greek and Roman agriculture.[6] Bulls, of course, were kept to ensure the continuation of the species as well as for food, but this was much rarer. The ratio of cows to bulls could be 40:1, and bulls are high upkeep, dangerous, and of little utility. Thus, any given farmer would have oxen for plowing, likely a cow for milk, and some larger farms would also have a bull.

Which is the shor of Exodus 21? The question of which animal is being pictured here is important, since the implications of the law would be different depending on which is envisioned.

Imprecision of Biblical Hebrew on Bovine Related Matters

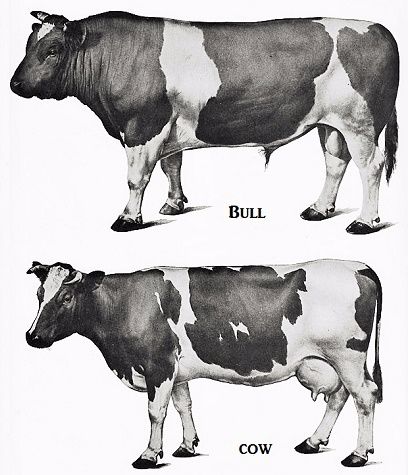

It is worthwhile to clarify the relevant terms in English. The word cow refers to a mature female bovine, and heifer is the term for a young cow, especially one that has not yet had a calf. The term calf in English refers to the young of a cow and is neutral in terms of gender. Regarding males, there are finer distinctions. Bull calf is the label for a young male, which will grow into a bull if it is left intact. However, if castrated, he will grow into a steer, and in about two or three years become an ox. While the term ox can be used generally for any domesticated bovine, its more correct and technical referent is a “castrated mature male of the domesticated cattle species,” either Bos Taurus or descendants of the Bos Primigenius.[7]

It is worthwhile to clarify the relevant terms in English. The word cow refers to a mature female bovine, and heifer is the term for a young cow, especially one that has not yet had a calf. The term calf in English refers to the young of a cow and is neutral in terms of gender. Regarding males, there are finer distinctions. Bull calf is the label for a young male, which will grow into a bull if it is left intact. However, if castrated, he will grow into a steer, and in about two or three years become an ox. While the term ox can be used generally for any domesticated bovine, its more correct and technical referent is a “castrated mature male of the domesticated cattle species,” either Bos Taurus or descendants of the Bos Primigenius.[7]

Biblical Hebrew is much less precise than English regarding terms for cattle, which makes it difficult to determine if a given biblical text is discussing an ox, a cow, or a bull. The English term “yoke of oxen” (tzemed baqar) might presume that the pair is castrated, but the Hebrew baqar, “large cattle,” allows no such determination.

The Hebrew word shor indicates a single head of large cattle, without any indication of age, gelding, or gender,[8] it can be translated “bull” or “ox” or even “cow.”[9] The same is true of the Akkadian word alpum.[10] Thus, it is unclear if in this law, the Torah is envisioning an ox, a bull, or maybe both.[11] Translators of the Bible have differed in their rendering of this term in English; some have “bull,” and others have “ox.”[12] Most modern commentaries offer no clarification.[13]

Law against Gelded Animals as Sacrifices

That shor can refer to either bull or oxen is clear from the law against sacrificing gelded animals (Lev. 22:23-25):

ויקרא כב:כג וְשׁוֹר וָשֶׂה שָׂרוּעַ וְקָלוּט נְדָבָה תַּעֲשֶׂה אֹתוֹ וּלְנֵדֶר לֹא יֵרָצֶה: כב:כד וּמָעוּךְ וְכָתוּת וְנָתוּק וְכָרוּת לֹא תַקְרִיבוּ לַיהוָה וּבְאַרְצְכֶם לֹא תַעֲשׂוּ: כב:כה וּמִיַּד בֶּן נֵכָר לֹא תַקְרִיבוּ אֶת לֶחֶם אֱלֹהֵיכֶם מִכָּל אֵלֶּה כִּי מָשְׁחָתָם בָּהֶם מוּם בָּם לֹא יֵרָצוּ לָכֶם:

Lev. 22:23 You may present as a freewill offering a shor or a sheep with a limb extended or contracted; but it will not be accepted for a vow. 22:24 You shall not offer to YHWH anything with its testes bruised or crushed or torn or cut. You shall have no such practices in your own land, 22:25 nor shall you accept such animals from a foreigner for offering as food for your God, for they are mutilated, they have a defect; they shall not be accepted in your favor.

The above law is the basis for Judaism’s ban on the castration of animals in general, even outside of sacrifices.[14] Whatever the intent of the passage, however, the biblical authors clearly are aware of the practice (and utility) of castrating bulls and distinguish between a shor that may be sacrificed (bull) and a shor that may not be (ox). Still, it does not change the term for the animal in question. Biblical Hebrew, thus, offers the reader no specific terms for the ox as opposed to the bull.

The Docility of Oxen

Pre-modern farmers as well as farmer in developing countries, have two main incentives to castrate or geld their bulls.

Breeding purposes – Farmers may wish to prevent inferior males from passing on their undesirable traits. For the purpose of insemination, the necessary ratio was about one bull for every forty cows, therefore most males could be made into oxen, eaten, or used for sacrifices.

Docility – Oxen are more docile. This means they can be trained with greater facility to pull a plow or cart,[15] and it also means that they are easier to manage in general and less dangerous. Oxen are less prone to gore or violently attempt copulation with a nearby cow than bulls, who are very aggressive and must be constantly penned up and/or monitored.

Jonathan Fisher, who wrote about “Scripture Animals” in the 19th century, attests that,

In most civilized parts of the world, Bulls, except so many as are needed for propagating, are altered usually while calves; then from about one to three years old, we call them Steers, after that, Oxen. The Ox is usually very gentle; grows to a size much larger than the Bull; is much taller, has longer horns, and the hair of his front is much less curled; so that he seems to be almost another species of animal. In this state he is exceedingly useful; he draws the wagon, the cart, and the plough, and is used for almost all kinds of draught. He is very patient in labor. He is in a sense, the wealth of the farmer.[16]

Oxen as Draft Animals in the Bible

The Bible offers ample testimony to the use of large cattle (i.e., oxen or cows, certainly not bulls!) as draft animals.

- Cows were used for pulling the Ark from Philistine country to Judah (1 Samuel 6:7).

- Large cattle (shor and baqar) participated in pulling the wagons for the initiatory gifts of the chieftains for the Tabernacle (Numbers 7:3).

- The Torah refers to the ritual use of a cow (eglah) which had never bore a yoke which suggests that the opposite was the norm (Numbers 19:2, Deuteronomy 21:3).

- The term tzemed baqar, “a yoke of oxen,” assumes the use of large cattle in plowing.[17]

- Deuteronomy refers to large cattle (shor) threshing and plowing (22:1, 25:4),

- Exodus 23:12 mandates that the shor rest on the Sabbath.

- Proverbs 14:4 praises the contribution of cattle as draft animals:

בְּאֵין אֲלָפִים אֵבוּס בָּר וְרָב תְּבוּאוֹת בְּכֹחַ שׁוֹר

“If here are no oxen the crib is clean, but a rich harvest comes through the strength of an ox.”

But is it the docile draft animal or the raging bull that is pictured as the gorer in Exodus?[18]

Bull: The More Aggressive Option

Gary Rendsburg translates the expression shor naggaḥ (Exodus 21:29) as “goring bull” and notes,

Most ancient Near Eastern languages, Hebrew and Akkadian among them, do not distinguish between “bull” and “ox.” Accordingly, many scholars call this case ‘the goring ox.’ But oxen (who because they have been castrated, are quite docile) are much less likely to gore than bulls (whose strength and virility are well known).[19]

The “gorer” of v.29, unlike the bovine of v.28, is a repeat offender whose owner has been warned by local authorities and is aware of his animal’s attacks on other animals or people. Such habitual violence would be very unlikely for the docile ox, an observation that leads Rendsburg to translates shor as “bull.”

Ox: A Docile Animal that Gores

Rendsburg’s point can be turned on its head, however. Would the owner of a bull allow his virile and potentially lethal beast to roam where it has access to vulnerable people and other animals? If the Bible indeed speaks of a bull here, one would expect the penalty for the negligent owner to be harsh even for a first offense because the aggressive nature of a bull is so predictable.

Thus, it seems reasonable to suggest that the subject of legislation here is the more docile ox precisely because its tendency to lethal destruction is more difficult to foresee. Therefore, the owner of a first-time offender “is not to be punished” (v. 28) and suffers “only” the loss of his beast by stoning,[20] whereas the owner of a repeat offending ox should have known better and kept better watch.

An important legal difference between my suggestion and that of Rendsburg is that if the Torah is discussing a bull, the law should be the same for the case of an ox, only the Bible wasn’t picturing an ox since a goring ox would be an unusual occurrence. If it is picturing an ox, however, the owner of a bull should always be liable; in rabbinic terms: bull muad le-olam.

Juristic Fascination and Legal Theory

The unusual image of a docile ox repeatedly goring people may be a reflection of the theoretical nature of these laws. Remarkably, of the thousands of court documents from the many centuries of ancient Near Eastern history, only one legal tablet, found in Nuzi (in modern Iraq; ca. 1500 BCE), speaks of an actual case of the damages incurred when one ox killed another.[21] Similarly, no rabbinic text to my knowledge deals with an actual case of a homicidal or bovicidal ox. Now, it must have happened on occasion that large cattle got out of control with lethal consequences, but perhaps the damages were handled privately and weren’t so complicated as to produce court documentation.

Modern scholars suggest that the appearance of the goring ox in these ANE law collections reflects ancient jurists’ fascination with the ambiguity of property which possesses will but not human intelligence.[22] The same would be true of the biblical collection.

And yet, despite the abundant literature generated by the bovine that gores with lethal consequences, the status of the beast remains an open question: is it an ox, the more common and highly valued asset for which violence is less characteristic, or the bull, the animal known to gore, but for that very reason would not be released to wander?

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

February 19, 2017

|

Last Updated

November 18, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Elaine Goodfriend is a lecturer in the Department of Religious Studies and the Jewish Studies Program at California State University, Northridge. She has a Ph.D. in Near Eastern Studies from U.C. Berkeley. Among her publications are “Food in the Hebrew Bible,” in Food and Jewish Traditions (forthcoming) and “Leviticus 22:24: A Prohibition of Gelding for the Land of Israel?”

Essays on Related Topics: