Op-ed

Ending the Battle Against Academic Biblical Studies

A Dati Israeli Blogger’s Perspective

Yeshivat Mercaz HaRav, April 2015. אפרים רוזנפלד, Wikimedia

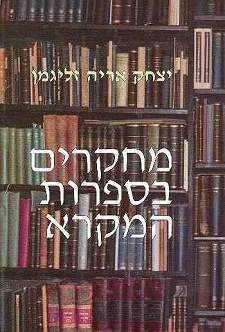

The story goes that Rabbi Prof. Y. A. Seligman used to announce his students, with his large kippah on his head: “Today we will prove, beezrat hashem, that not all the Torah was given to us from Moshe rabbeinu…” [1]

Many Orthodox Jews perceive such a statement as heresy – even if it is cited from a halachically observant rabbi. Even some Orthodox Bible scholars, who are surely aware of the modern academic findings in this area, would take issue with Seligman’s tone. A number of them would take refuge in the literary-synchronic approach, which relates to the scripture as a whole, rather than the critical-diachronic approach, which relates to it as a collection of sources, traditions and redactional layers.

Many Orthodox Jews perceive such a statement as heresy – even if it is cited from a halachically observant rabbi. Even some Orthodox Bible scholars, who are surely aware of the modern academic findings in this area, would take issue with Seligman’s tone. A number of them would take refuge in the literary-synchronic approach, which relates to the scripture as a whole, rather than the critical-diachronic approach, which relates to it as a collection of sources, traditions and redactional layers.

The main reason for the reluctant attitude towards academic biblical studies[2] is, of course, the fact that its findings directly contradict the simple articulation of one of the Jewish principles of faith, Torah min-Hashamayim (TMS), that the Torah is from heaven. This belief is one of the few that enjoyed a consensus among Jewish groups from Second Temple through pre-modern times.[3]

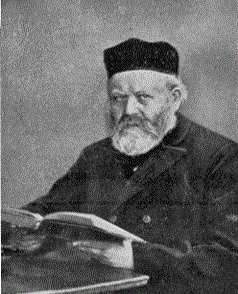

Additionally, another issue reinforced the religious discomfort caused by Bible criticism – some of the first Bible scholars, and Julius Wellhausen in particular, were German Protestants, with anti-Jewish affiliations. Solomon Schechter famously dubbed Welhausen’s “higher criticism” “higher anti-Semitism.” This unfortunate fact turned what could have been an evolving academic study of the Torah into a ‘personal’ issue, an all-out war of “all or nothing.”

Orthodox Responses to the Challenge of Academic Bible

The Orthodox reaction to Bible criticism since the turn of the 19 century, focused almost solely on Wellhausen’s formulation of the documentary hypothesis (DH) – as if bible scholarship was only about DH. Just as Schrödinger’s cat has become a symbol of quantum theory, so too has Wellhausen become the symbol of academic biblical studies. Orthodox Bible scholars felt that if only they could prove that “Wellhausen’s Cat” (more accurately “predacious lion”) was totally dead, then the great heresy would vanish and the belief in TMS will be reestablished.

Rabbi Prof. David Zvi Hoffmann was the first to try and kill the lion by scientifically disproving it on academic grounds. But he concedes that he was never really willing to consider Wellhausen’s view as an option:

I willingly admit that based on the principles of my belief I couldn’t conclude that the Pentateuch was written after the days of Moses or by someone other than Moses, but aspiring to scientifically establish these principal assumptions, I have always tried to argue only such arguments that others – who have basically different assumptions – can acknowledge as correct.”[4]

Considering his clear and articulated religious bias, his views did not garner much academic acknowledgement outside of the Orthodox community.

A more significant attack on Wellhausen’s thesis, academically speaking, came from Rabbi Prof. Moshe David (Umberto) Cassuto and Prof. Yehezkel Kaufmann, each in his own way.[5]Both scholars claimed not only to have killed the lion, but even to have skinned it and cast it aside like the proverbial “despised broken pot” (Jer. 22:28).

At first blush, this was very exciting to some traditional scholars, but, in reality, the problem for religious Jews only became worse. Unlike Hoffmann, neither Cassuto nor Kaufmann had any inclination to replace Wellhausen with Mosaic authorship or Torah from heaven.[6]Cassuto believed that the Torah, although a unitary document, was a human composition derived from written and oral traditions. Even worse, Kaufmann accepted the idea of the Documentary Hypothesis, but objected to Wellhausen’s late dating of P and his skepticism about the early nature of Israelite monotheism.

Rabbi Dr. Mordechai Breuer, a later Orthodox scholar who responded systematically to Wellhausen and his school, came up with the “aspects theory” (shitat hebchinot).[7] According to this theory, which tries to scrape honey from the dead lion’s carcass, although the Torah writes from a number of perspectives and in a number of voices, the multivocality of the Torah is original, purposeful and divine.[8]

Nevertheless, Breuer found out that his honey wasn’t suited to the taste of his fellow Torah scholars. Even those who reference his view as an option don’t really make use of his theory in any robust way. Breuer would eventually reflect on this with bitterness, declaring that “even today [1998] they don’t understand me.”[9] Needless to say, many among his academic colleagues perceived his theory as an apologetic sham.[10]

The Challenge of Evolution vs. the Challenge of Academic Biblical Studies

In short, the challenge posed by academic biblical scholarship to classic iterations of Torah min HaShamayim (TMS) remains a live one. This question stands out as particularly problematic, at least socially, if we compare it to the questions of evolution or the world’s age and how they have been treated among contemporary religious groups and authorities. Each of these questions came to the fore in the 18th and 19th centuries, around the same time that the discipline of academic biblical studies was beginning to take root.

Nevertheless, at least in the Modern Orthodox community, these problems are less explosive. A rabbi who accepts the fact that the universe was created billions of years ago will find many defenders in the Orthodox community. Just look at the robust support Rabbi Natan Slifkin, the Zoo Rabbi, received when he was attacked for adopting the scientific theory of evolution as a legitimate “Torah-true” position. Thus far, this has not been the case for an Orthodox rabbi who publicly accepts that the Torah is a product of multiple authors, as can be seen in the recent tumult regarding this website and, in particular, Rabbi Dr. Zev Farber’s manifesto .

Why should a Religious Jew Study the Bible Academically?

It is my belief that that, in our era, academic study of the Bible should be engaged in lechatchila, and not for apologetic reasons. There are at least three good reasons for this:

First, there is the basic human desire to know the “truth” as much as we can discover it through the foggy layers of time and the various fissures in the biblical verses. (Sadly, we must admit that this desire for truth is one that the Orthodox education system manages to suppress almost entirely.) How can we be dedicated to truth but then ignore what academic scholarship teaches us?

Second, biblical studies is one of the most diverse and absorbing areas of academic research. Putting aside the religious objections for a moment, considering the paramount importance of Torah study to religious Jews, it is difficult not to want to learn the academic approach, which is so rich and chock-full of insights into the meaning of our holiest of books.

Third, there is an urgent need to react to the earth shattering occurrences of this past century, namely the Holocaust and the founding of the State of Israel. If until recently, believing Jews could remain enclosed in their dalet amos of traditional Torah and maintain their simple faith, the incidents of the mid-twentieth century turned the basic realities and articles of Jewish life in their heads: For many, both the dogma of divine retribution and that of divine providence were turned to ashes by the crematoria. Similarly, the belief in mashiach(messiah) became redundant after the secular miracle of kibbutz galuyot and the establishment of Israel.

It is precisely here where I find biblical scholarship’s insights helpful, since we now know that ‘ancient Israel’ (namely, our ancestors!) also faced tremendous changes in its reality, and had to cope with theological questions similar to ours. In contrast to us, the biblical authors dealt with re-valuating of their faiths, and even with adjusting the divine laws given from heaven, by rewriting and editing the ancient texts.[11]

To be clear – admitting human involvement in the shaping of the Torah does not necessarily mean denying the historicity of its stories (in general, even if not in details). The enslavement in Egypt, the exodus, the wandering in the desert – all of these are fundamental narratives in which the Ancient Israelites (including the authors of the Pentateuch) believed. The fact that our ancestors bothered to write down their versions of these stories implies only this: The Bible is not the Israelite belief’s raison d’être, rather the Israelite belief is the Bible’s raison d’être![12]

It Is Time

For all of these reasons and more I believe we Orthodox Jews need to end the battle against academic biblical studies and begin to incorporate it into our overall religious framework. Doing so will be challenging, and a condemnation of ‘heretic’ or ‘reformer’ is more than expected – but I also believe that it will be valuable in our attempt to find solutions to some of the problems referenced above.

Change is frightening, even when it is necessary. I understand this fear and I even admit that the consequences of such a change are unpredictable. Nevertheless, I believe this step is necessary and inevitable.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Footnotes

Dr. Avi Dentelski holds a Ph.D. in Bible studies from Ariel University, where he also earned his M.A. degree (summa cum laude). His dissertation deals with chance and accidentalness in the biblical historiography and in post-biblical theology. Avi is the author of the “ארץ העברים” blog, where he shares his insights on Bible, Judaism and… flamenco (his hobby).

.jpeg)