Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Joshua’s Altar on Mount Ebal: Israel’s Holy Site Before Shiloh

A view of Mt. Ebal from Mt. Kabir. Photo by תמר הירדני – wikipedia

Archaeology: Excavation and the Survey

The best-known technique in archaeology is the excavation, in which a given site is dug carefully to understand it in detail.[1]In Israel, these sites are commonly tels, areas that were settled over generations, with one settlement built on top of the other, sometimes for millennia.

Another technique in archaeology, which has increasingly become a staple of archaeological research over the past decades, is the survey. This involves walking systematically over a given area and recording every surface find. Other than remains of architecture, the most significant—and certainly the most prevalent—find is pottery.[2] Quantities of pottery in a concentrated area indicate ancient habitation, and suggests a date range for the site, as pottery styles changed frequently, and can be dated to within decades of its manufacture.

Surveys offer us a landscape, indicating important sites that may have been overlooked, and what the overall settlement periods may have been in any given area.

The Manasseh Hill Country Survey Encounters El-Burnat

In the late ‘70s, Israeli archaeologists embarked on an intensive campaign to survey a number of regions that play an important role in the Bible. Adam Zertal (1936–2015) of Haifa University ran a survey of the Manasseh Hill Country and Israel Finkelstein of Tel Aviv University surveyed the Ephraim Hill Country.[3]

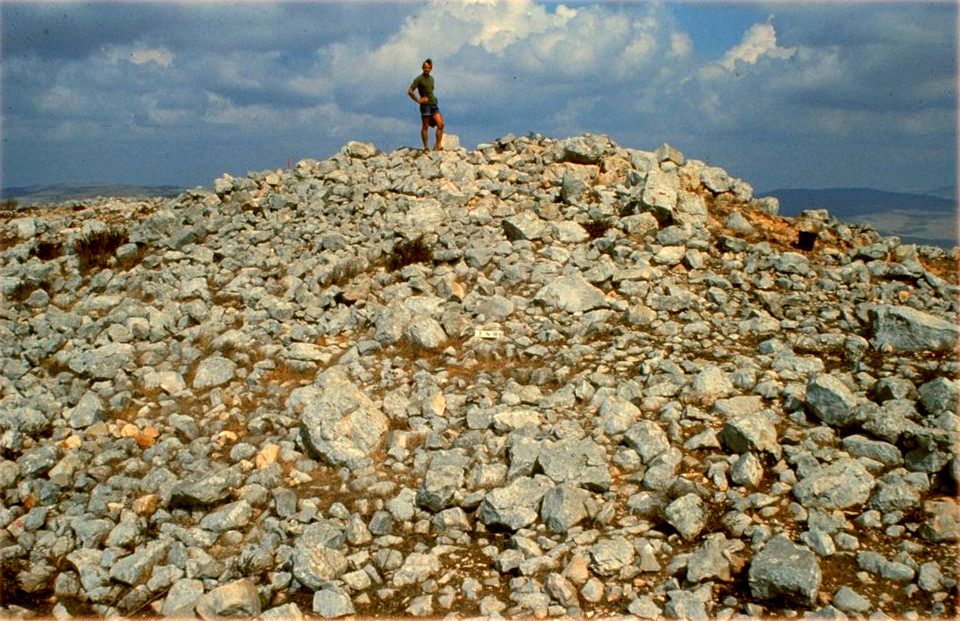

As part of Zertal’s survey, he encountered a site on the northeastern slope of Mt. Ebal, 940 meters above sea level, and 60 meters below the summit, in a naturally occurring amphitheater (i.e., a spot where a steep mountain or a particular rock formation naturally amplifies or echoes sound). The site is known as El-Burnat, Arabic for “the hat,” likely because, before excavation, it was a large, hat-like pile of rocks.

Zertal noted a variety of interesting archaeological indicators, such as thousands of pottery shards all dated to Iron I (twelfth-eleventh cent. B.C.E.), an unusually large mound of stones, and a variety of walls jutting out in different parts of the site. These made the site worthy of a full-fledged excavation, which he conducted there for eight seasons (1982–1989).[4] Zertal discovered that the site was inhabited for only about a century and had two phases:

Earlier Phase – The first settlement, built on bedrock ca. 1250 B.C.E., which Zertal labeled Stratum II,[5] consisted of a small structure in area A labeled “Installation 94,” divided by a thin wall. An early Israelite style, four-room house was uncovered in area B, in which a grain silo, storage jars, lamps, and collared-rim jars were found. The entire area was enclosed by walls, two of which abutted the four-room house.

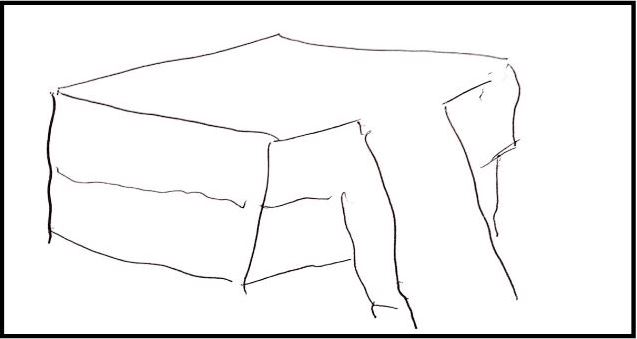

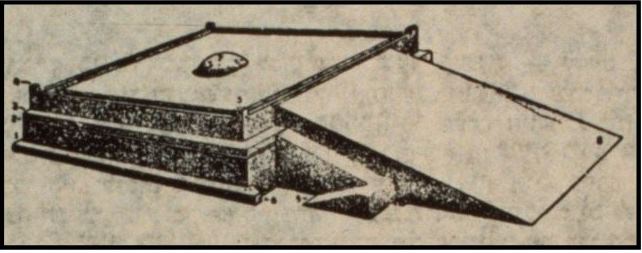

Later Phase – The site was heavily remodeled in the second phase, which Zertal labeled Stratum IB. Upon the small structure in area A, a large (9 x 14 m) rectangular structure was built, made of field (i.e., unhewn) stones. The structure seems to have no entrance of any kind. Also, no evidence of a packed earth floor was found.

Inside the structure are two field stone walls (labeled “walls 13 and 16”) opposite each other that extend part way into the enclosed space, as if dividing the inside into two spaces with access from one to the other. The walls do not meet, however, but stop at either end of Installation 94, which was part of the older stratum. At first, these look like rooms, but the structure has no doors, so it is more likely that these walls were designed to allow people to walk on the top of the structure.

Finally, Zertal uncovered the remains of what seems to have been a 2-meter-high ramp leading to the top of the structure, and descending 7 meters (at a 22◦ incline) to the bottom. On either side of this ramp was a shorter ramp, leading to the ledges on the two sides of the structure. At the bottom of the ramp there were two paved courtyards, one on each side, in which a number of installations and pottery remains were found. This entire complex is surrounded by a very low wall (only 1 meter high).

Area B went through a similarly extreme renovation, in which the entire house was covered with stones to make a paved courtyard, with three stairs leading up to a gate to the complex area. Like Stratum II, Stratum IB was surrounded by an outer wall delimiting the area.

Burying the Site – This ritual complex existed for less than a century, after which it was deliberately covered with stones. This was likely done to both decommission the site and to protect it from being looted or reused. Zertal labeled this covering Stratum IA, and dated it to around 1140 B.C.E.

Discovering a Buried Altar?

The rectangular building was unlike anything else ever excavated in the Levant. During the third season of the ensuing excavation, Zertal made a drawing of the central structure showing how he thought it would look once it was completely uncovered. At the time, I was a volunteer working on the excavation team, and as soon as Zertal passed the drawing to me, it hit me that I knew what we were looking at since I had seen a very similar drawing once before.[7]

|

|

| A drawing of the structure similar to Zertal’s | Drawing of Altar from the Mishna, Middot ch. 3 |

I quickly ran to the library to get a copy of Mishnah, Tractate Middot (ch. 3; Mishnah Mevuoret edition), and showed Adam a drawing very like his own: It was an artist’s rendition of the altar of the Second Temple in Jerusalem based on the Mishnaic text. Both the Mishnaic text and the rectangular structure uncovered at El-Burnat would have been much larger than other ancient Levantine altars we know from excavations. Nevertheless, such a structure does seem to be in line with a number of biblical and post-biblical notions about how to build altars.[8]

Field Stones – The entire structure was made of whole, uncut fieldstones, which conforms to the command in Exodus 20.[9]

שמות כ:כא מִזְבַּח אֲדָמָה תַּעֲשֶׂה לִּי וְזָבַחְתָּ עָלָיו אֶת עֹלֹתֶיךָ וְאֶת שְׁלָמֶיךָ אֶת צֹאנְךָ וְאֶת בְּקָרֶךָ…כ:כב וְאִם מִזְבַּח אֲבָנִים תַּעֲשֶׂה לִּי לֹא תִבְנֶה אֶתְהֶן גָּזִית כִּי חַרְבְּךָ הֵנַפְתָּ עָלֶיהָ וַתְּחַלְלֶהָ.

Exod 20:21 Make for Me an altar of earth and sacrifice on it your burnt offerings and your sacrifices of well-being, your sheep and your oxen… 20:22 And if you make for Me an altar of stones, do not build it of hewn stones; for by wielding your tool upon them you have profaned them.

According to this verse, more than one type of altar is acceptable, but if the altar is to be made of stones, they must be field stones and uncut. Altars made of ashlar (neatly cut) stones, such as we find in Tel Dan and Tel Beersheba, violate this rule.

Ramp – The ramp to the top of the structure conforms to another rule in the very next verse:

שמות כ:כג לֹא תַעֲלֶה בְמַעֲלֹת עַל מִזְבְּחִי אֲשֶׁר לֹא תִגָּלֶה עֶרְוָתְךָ עָלָיו.

Exod 20:23 Do not ascend My altar by steps, that your nakedness may not be exposed upon it.

Any very large altar would need to have either stairs or a ramp to allow the priests access to the top. An example of an altar with stairs is the massive Early Bronze II-III (2950–2350) circular altar in Megiddo. Of course, this is from a much earlier period, but it is an example of what the author of Exodus 20:23 does not want, and what the people who constructed the altar on Ebal did not build.

Ledge – The structure is surrounded on three sides by a ledge, which would allow anyone walking upon it access to the top of the structure. (In rabbinic literature, such a ledge is called the סובב, “surrounder or perimeter,” and some scholars assume that this is the meaning of the biblical יסוד “foundation,” at the feet of which sacrificial blood was poured.) According to the descriptions of sacrificial rites in the Torah, the priests would have sprinkled blood on multiple sides of the altar, and at the top, including sometimes on each of the four corners of the altar. This could not be accomplished easily without a ledge, as otherwise the priest would need to walk on the altar itself.

Inner Walls – The two inner walls (13 and 16) would allow priests access to the middle of the structure, which they lead to on either side. Rabbinic literature refers to a circular mound in the middle of an altar called the תפוח (tapuach, m. Tamid2:2), which is where the sacrifices would be burned and the ashes would be piled up. It is hardly coincidental that the center point sits precisely above Installation 94, which itself was likely an altar that was used by the inhabitants of the previous stratum. In other words, sacrifices would be offered from the same consecrated spot. Finally, as field stones are not susceptible to impurity according to biblical law, they would be an ideal material for the priests to walk upon.

Other Ritual Details that Fit with Biblical Law

Not only does the structure of the building fit with the biblical picture, but certain aspects of the building fit well with other ritual laws and concepts known from the Bible.

Kosher animal bones – The structure is mostly hollow on the inside (with the exception of the two parallel partial walls described above), and it was filled to the top in ancient times. The filling is a mix of dirt, ashes, pottery sherds, and more than three thousand animal bones. These bones had been burnt on an open flame, and many had butcher marks, implying that at least parts of them had been eaten.

These bones were all from animals that the Torah declares to be pure; the overwhelming percentage of the specimens were year-old male cattle, sheep and goats, all sacrificial animals according to biblical law. This points to the likelihood that the new structure was filled with the bones of the sacrificial animals offered on the older structure, also an altar.

Admittedly, fallow deer (יחמור), the bones of which were also found in the structure, are not sacrificial animals according to the Bible, but they are still pure animals, permitted for Israelite consumption. Perhaps these bones were of animals consumed but not sacrificed (remember that the site was occupied by Israelites for decades before the large structure was constructed). Alternatively, perhaps non-Torah traditions allowed fallow deer to be sacrificed.

Separation wall – The 1-meter high inner-wall surrounding the structure[10] would not have been high enough to keep people out. It therefore seems like something that would demarcate space, so that people would know where they may stand and where they may not. Such demarcations often serve to divide between priests and non-priests, or pure and impure, in ritual contexts.

Foundation Deposits – Two Egyptian scarabs, one of which was a royal scarab, were buried in situ at Ebal. The royal scarab appears to be “foundation deposit” or votive offering, i.e., a valuable item buried as a gift to a god.

Such foundation deposits are most common in cultic buildings.

Similarly, a unique decorated, chalice-shaped vessel made of soft pumice (volcanic stone) was found underneath the structure (Pit 250) in what seems to be a favissa, i.e., a collection of buried goods. The object itself has no clear parallels, but the closest are the stone vessels excavated by Flinders Petrie in Serabit el-Khadim in the Sinai Peninsula, which Petrie interpreted as small incense altars. This would imply that the object was a decommissioned cultic vessel, buried underneath the structure to protect it.

A 20-second aerial video of Ebal which was recently taken with a drone by Norwegian journalists writing about the site. When Avigdor Shinan saw the video, shortly after he visited the site, he said: אבנים שותקות מדברות לפעמים הרבה יותר מאשר מילים “Silent stones sometimes say much more than words”.

From all of the above, Zertal concluded that El-Burnat stratum IB was a cultic site, i.e., a bamah or high place,[11] with a massive stone altar as its main installation. Yet, from the time of Zertal’s first publication of his theory, many scholars reacted quite aggressively and dismissively. (See appendix for a discussion of alternative suggestions, and the suggested problems with each.)

Partly, this harsh reception was due to his having announced the finds brusquely in the popular journal, Biblical Archaeology Review, as opposed to opening with a more guarded statement in a blind, peer-reviewed academic venue. Yet the real issue was less with the idea that the structure was an altar, and more with the corollary to his claim: Zertal was not merely saying that this was an ancient Israelite altar, but that this was a specific altar, one described in detail twice in the Bible.

Joshua’s Altar on Mount Ebal

Towards the end of Deuteronomy, Moses issues the following command to the Israelites:

דברים כז:ד וְהָיָה בְּעָבְרְכֶם אֶת הַיַּרְדֵּן תָּקִימוּ אֶת הָאֲבָנִים הָאֵלֶּה אֲשֶׁר אָנֹכִי מְצַוֶּה אֶתְכֶם הַיּוֹם בְּהַר עֵיבָל וְשַׂדְתָּ אוֹתָם בַּשִּׂיד.כז:ה וּבָנִיתָ שָּׁם מִזְבֵּחַ לַי-הוָה אֱלֹהֶיךָ מִזְבַּח אֲבָנִים לֹא תָנִיף עֲלֵיהֶם בַּרְזֶל. כז:ו אֲבָנִים שְׁלֵמוֹת תִּבְנֶה אֶת מִזְבַּח יְ-הוָה אֱלֹהֶיךָ וְהַעֲלִיתָ עָלָיו עוֹלֹת לַי-הוָה אֱלֹהֶיךָ. כז:זוְזָבַחְתָּ שְׁלָמִים וְאָכַלְתָּ שָּׁם וְשָׂמַחְתָּ לִפְנֵי יְ-הוָה אֱלֹהֶיךָ. כז:ח וְכָתַבְתָּ עַל הָאֲבָנִים אֶת כָּל דִּבְרֵי הַתּוֹרָה הַזֹּאת בַּאֵר הֵיטֵב.

Deut 27:4 Upon crossing the Jordan, you shall set up these stones, about which I charge you this day, on Mount Ebal, and coat them with plaster. 27:5There, too, you shall build an altar to YHWH your God, an altar of stones. Do not wield an iron tool over them;27:6 you must build the altar of YHWH your God of unhewn stones. You shall offer on it burnt offerings to YHWH your God, 27:7 and you shall sacrifice there offerings of well-being and eat them, rejoicing before YHWH your God. 27:8 And on those stones you shall inscribe every word of this Teaching most distinctly.

The book of Joshua records Joshua’s fulfillment of this command:

יהושע ח:ל אָז יִבְנֶה יְהוֹשֻׁעַ מִזְבֵּחַ לַי-הוָה אֱלֹהֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל בְּהַר עֵיבָל.ח:לא כַּאֲשֶׁר צִוָּה מֹשֶׁה עֶבֶד יְ-הוָה אֶת בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל כַּכָּתוּב בְּסֵפֶר תּוֹרַת מֹשֶׁה מִזְבַּח אֲבָנִים שְׁלֵמוֹת אֲשֶׁר לֹא הֵנִיף עֲלֵיהֶן בַּרְזֶל וַיַּעֲלוּ עָלָיו עֹלוֹת לַי-הוָה וַיִּזְבְּחוּ שְׁלָמִים. ח:לב וַיִּכְתָּב שָׁם עַל הָאֲבָנִים אֵת מִשְׁנֵה תּוֹרַת מֹשֶׁה אֲשֶׁר כָּתַב לִפְנֵי בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל.

Josh 8:30 At that time Joshua built an altar to YHWH, the God of Israel, on Mount Ebal, 8:31 as Moses, the servant of YHWH, had commanded the Israelites — as is written in the Book of the Teaching of Moses — an altar of unhewn stone upon which no iron had been wielded. They offered on it burnt offerings to YHWH, and brought sacrifices of well-being. 8:32 And there, on the stones, he inscribed a copy of the Teaching that Moses had written for the Israelites.

According to this text, the Israelites built an altar for burnt-offerings on Mount Ebal at the beginning of the settlement period. This, Zertal argued, is the structure that he found: the altar referenced in Deuteronomy 27 and Joshua 8. Not only does El-Burnat date to this period (early Iron I), but it is the only site on all of Mount Ebal that does.

Moreover, since the site was buried under stones (Stratum IA) in around 1140 B.C.E., the tradition behind this text—perhaps even the text itself—must go back to this period. In other words, the author of Deut 27:5-7 either saw the altar while it was in use, or knew from tradition, after it was decommissioned in the mid-twelfth century, what lies under those rocks. Either way, the account of an altar on Mount Ebal must have been based on factual knowledge that only someone living in the early Iron I could have had.

The icing on the cake, as it were, is that we found flat plaster-covered stones buried inside the altar, which is consistent with the biblical references to plastered stones with writing upon them.[12]

Mount Gerizim – The Samaritan Pentateuch Problem

Zertal’s argument is based on the Masoretic Text (MT) of Deut 27:4 and Josh 8:30, which state that the altar was built on Mount Ebal. This is also the text of the Septuagint (LXX). However, the Samaritan Pentateuch (SP)[13] reads Mount Gerizim instead of Mount Ebal:

| Deut 27:4, MT | Deut 27:4, SP |

| Upon crossing the Jordan, you shall set up these stones, about which I charge you this day, in Mount Ebal, and coat them with plaster. | Upon crossing the Jordan, you shall set up these stones, about which I charge you this day, in Hargerizim (=Mount Gerizim),[14] and coat them with plaster. |

|

וְהָיָה בְּעָבְרְכֶם אֶת הַיַּרְדֵּן תָּקִימוּ אֶת הָאֲבָנִים הָאֵלֶּה אֲשֶׁר אָנֹכִי מְצַוֶּה אֶתְכֶם הַיּוֹם בְּהַר עֵיבָל וְשַׂדְתָּ אוֹתָם בַּשִּׂיד.

|

והיה בעברכם את הירדן תקימו את האבנים האלה אשר אנכי מצוה אתכם היום בהרגריזים ושדת אתם בשיד.

|

The logic of the Samaritan reading is clear: In the ritual of blessings and curses that is supposed to take place in this area, Mount Gerizim is the mountain of blessing and Mount Ebal is the mountain of curses (Deut 11:29; 27:11-13). Why would the altar be placed on the mountain of curses?[15]

The Samaritans further suggest that the reading “Mount Ebal” in the Jewish MT is a polemical adjustment on the part of the Jews to discredit the Samaritan holy mountain, and many scholars agree.[16] And yet, a number of factors provide strong support for the opposite scenario, that MT is original, and the Samaritan text was adjusted to support their Temple.

First, unlike Mount Ebal, which has El-Burnat, no Iron Age remains exist at all on Mount Gerizim, whose earliest structures date to the Persian period. Thus it is hard to imagine that this text can be a reference to Gerizim unless one dates it to the late Persian Period. Moreover, it seems an unlikely coincidence for MT to choose Ebal for polemical reasons and just happen to pick a mountain with a twelfth century B.C.E. ritual site.

“ON Gerizim” but “IN Ebal”

Geographic-linguistic evidence also suggests the priority of the MT. Later in Deuteronomy 27, where these mountains are mentioned, in both MT and the SP, the people stand “on” (על) Mount Gerizim, but “in” (ב) Mount Ebal:

| Deut 27:12-13, MT | Deut 27:12-13, SP |

| The following shall stand on Mount Gerizim to bless the people, after you have crossed the Jordan… And the following shall stand for the curse in Mount Ebal… | The following shall stand on Har Gerizim (=Mount Gerizim) to bless the people, after you have crossed the Jordan… And the following shall stand for the curse in Mount Ebal… |

|

אֵלֶּה יַעַמְדוּ לְבָרֵךְ אֶת הָעָם עַל הַר גְּרִזִים בְּעָבְרְכֶם אֶת הַיַּרְדֵּן… וְאֵלֶּה יַעַמְדוּ עַל הַקְּלָלָה בְּהַר עֵיבָל…

|

אלה יעמדו לברך את העם על הרגריזים בעברכם את הירדן… ואלה יעמדו על הקללה בהר עיבל…

|

The preposition על means “on top of something,” whereas ב would not necessarily refer to the mountain’s summit. The distinction of prepositions here reflects the topography of the site, since El-Burnat is on the third of four slopes of Mt. Ebal, and is, therefore, not “on” the mountain, but rather “in” the mountain.

And yet, in the SP version of Deuteronomy 27:4, the altar is to be built “in” HarGerizim (בהרגריזים). This does not correspond to the topography of the mountain since the Samaritan cultic site on Gerizim was at the top of the mountain, not on a lower slope. The use of ב (“in”) in the SP indicates that a Samaritan scribe simply replaced Ebal with HarGerizim, but without updating the preposition to על (“on”).[17]

The Place God Will Choose

On a different point, however, the Samaritan interpretation of the text seems to be mostly correct. The book of Deuteronomy consistently refers to God’s holy place as “the place YHWH will choose” (מקום אשר יבחר י-הוה) in MT, or “the place YHWH chose” (מקום אשר בחר י-הוה) in SP. Jewish interpretation assumes this to be a reference to Jerusalem while Samaritans assume it is a reference to Gerizim.

The Samaritans believe that the phrase, which in their version is in the perfect tense, reflecting past action, must refer to the altar on Gerizim (MT Ebal), since this is the only holy spot that has been explicitly chosen in the book. Jewish interpretation, based on the use of the imperfect (future) verb, assume this is a reference to a future choice, and suggest it is a reference to Jerusalem, which is chosen as the site of the Temple in Samuel and Kings.

It is reasonable to follow the Samaritan suggestion that this verb refers to Joshua’s altar. As Ruth Walfish notes,[18] the episode of the Gibeonite trick (ch. 9) comes immediately after the account of Joshua building the altar on Mount Ebal (ch. 8). At the end of this episode, Joshua condemns the Gibeonites to perpetual servitude at the altar of YHWH:

יהושע ט:כז וַיִּתְּנֵם יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בַּיּוֹם הַהוּא חֹטְבֵי עֵצִים וְשֹׁאֲבֵי מַיִם לָעֵדָה וּלְמִזְבַּח יְ-הוָה עַד הַיּוֹם הַזֶּה אֶל הַמָּקוֹם אֲשֶׁר יִבְחָר.

Josh 9:27 That day Joshua made them hewers of wood and drawers of water—as they still are—for the community and for the altar of YHWH, in the place that He would choose.[19]

Clearly the altar of YHWH here, which is in “the place he would choose” refers to the altar just built in the previous chapter.

Choosing More than One Place?

Why does the MT use the imperfect verb in Deuteronomy and Joshua if Ebal was already chosen? Moreover, as the site was decommissioned and buried in 1140 B.C.E., in what way could this be the future cult center of Israel for all time, and in what way could the Gibeonite servitude be perpetual, lasting “until this very day,” i.e., well after the time of Joshua?

The answer is that the central cult place of Israel moved over time, and each counted as “the place that YHWH will choose.”[20] Jerusalem was not the first of these places, but the last; El-Burnat was the first. But why was the cultic area on Mount Ebal decommissioned?

Replacing Ebal with Shiloh

The books of Judges and Samuel, which tell the stories of the Israelites in the pre-Monarchic and early Monarchic period, before the building of the Jerusalem Temple, never mention Ebal and its altar. Instead, they focus on Shiloh. Judges 18:31, for example, describes a house of God (בית אלהים) at Shiloh, while 1 Samuel 1–4 refer to it as the place where Eli the priest served, and where the Ark of the Covenant was kept.

Both Judges 21 and 1 Samuel 1 describe it as a place of pilgrimage, where Israelites from other parts of land would come on special days to make offerings to YHWH. This tradition appears in other biblical books as well; Psalm 78:60, for instance, refers to an ancient tabernacle of Shiloh.

Shiloh too has been excavated. As noted above, whereas Adam Zertal conducted the survey of the Manasseh hill country, his younger colleague, Israel Finkelstein, conducted the survey of the Ephraim region, just south of Manasseh. He too found a cultic site, in Khirbet Seilun, which he identified with the biblical city of Shiloh, an identification that is generally accepted.

On October 14, 1983, while returning from Ebal to Jerusalem with the late Benjamin Mazar, I suggested we stop at Shiloh and ask Finkelstein what—in his opinion—was the beginning date of the Israelite cultic center there. He answered circa 1150 B.C.E., a date he later published.[21] The book of Judges is replete with stories about serious tension, even battles, between Manasseh and Ephraim. It is hardly coincidental that at the same time as a major cultic site was decommissioned in Manasseh, another one was established in Ephraim.[22]

It is a bit surprising that no explicit record of this switch is recorded in the Bible. I believe we have such a record, but in allegorical form.

Why Jacob Crossed his Arms

In Genesis 48, Joseph brings his two sons to his father, Jacob to bless. Although Joseph presents the older son, Manasseh, on Jacob’s right, Jacob crosses his arms, putting his right hand on the head of Ephraim.[23] Thinking this was in error, Joseph tries to move his father’s arms and when he cannot, he tells his father that he is making a mistake, that Manasseh is the older son.[24] Jacob responds:

בראשית מח:יט וַיְמָאֵ֣ן אָבִ֗יו וַיֹּ֙אמֶר֙ יָדַ֤עְתִּֽי בְנִי֙ יָדַ֔עְתִּי גַּם ה֥וּא יִֽהְיֶה־לְּעָ֖ם וְגַם ה֣וּא יִגְדָּ֑ל וְאוּלָ֗ם אָחִ֤יו הַקָּטֹן֙ יִגְדַּ֣ל מִמֶּ֔נּוּ וְזַרְע֖וֹ יִהְיֶ֥ה מְלֹֽא הַגּוֹיִֽם: מח:כוַיְבָ֨רֲכֵ֜ם בַּיּ֣וֹם הַהוּא֘ לֵאמוֹר֒ בְּךָ֗ יְבָרֵ֤ךְ יִשְׂרָאֵל֙ לֵאמֹ֔ר יְשִֽׂמְךָ֣ אֱלֹהִ֔ים כְּאֶפְרַ֖יִם וְכִמְנַשֶּׁ֑ה וַיָּ֥שֶׂם אֶת־אֶפְרַ֖יִם לִפְנֵ֥י מְנַשֶּֽׁה:

Gen 48:19 But his father objected, saying, “I know, my son, I know. He too shall become a people, and he too shall be great. Yet his younger brother shall be greater than he, and his offspring shall be plentiful enough for nations.” 48:20So he blessed them that day, saying, “By you shall Israel invoke blessings, saying: God make you like Ephraim and Manasseh.” Thus he put Ephraim before Manasseh.

This story is an allegory defending the fact that although the tribe of Manasseh was the first to dominate the hill country, its “younger brother” Ephraim soon took preeminence. Part of this preeminence was the moving of the central holy site from the former’s territory to the latter’s, from Ebal to Shiloh.

The Places YHWH Will Choose

Archaeology and text, therefore, both point in one direction. The first central cult site of the Israelites was in the territory of Manasseh, at the site of El-Burnat on Mount Ebal. This site is explicitly described by the books of Deuteronomy and Joshua. Over time, when the power moved from Manasseh to Ephraim, this site was respectfully decommissioned and buried, and a new central cultic site was founded at Shiloh. When Shiloh was destroyed, yet a new place had to be found, but that is already a different story.

Appendix

Responses to Reservations with Zertal’s Suggestion

A number of alternative suggestions have been put forth to explain the evidence at El-Burnat, but each is problematic.

Watchtower

The main alternative explanation for this structure came from Aaron Kempinski (1939–1994) soon after Zertal published his theory, who argued that the structure was the base of a watchtower.[25] But this suggestion is problematic for a number of reasons:

- The structure is far back from the peak of the ridge, which would be the optimal place for such a tower;

- The base is significantly larger than other watchtowers from this period;

- The presence of thousands of burnt animal bones is hard to explain;

- The structure labeled Installation 94 in Stratum II, upon which the new structure was built, also seems to have been an altar or a cultic site, implying that this spot was chosen for holiness and not site-lines.

In addition to these problems, Kempinski’s reconstruction of the area requires him to reinterpret the finds in a forced manner. To quote Ziony Zevit:

I agree with Zertal that the structural elements which Kempinski disassociated from each other in his proposed three-phase schematic history are actually bonded together in the original construction project and are not to be separated or disassociated from each other.[26]

Farmstead

Another approach was taken by the German archaeologist and biblical scholar, Volkmar Fritz, (1938–2007), who understood the entire area to simply be a farmstead. This was also the view of Anson Rainey (1930–2011), who interpreted the low wall as a corral, to pen in the animals. Rainey imagines the area as an out of the way place settled by one extended family, who would pasture their flocks there and grow cereals.[27]

But it is difficult to interpret the area as farming site:

- No sickle blades were found, and these are ubiquitous in farming sites;

- No bones of any work animals such as donkeys or horses, which would be expected in a farmstead, were found on the site.

- Of the approximately four thousand unique pottery vessels that were identified, only three were lamps. This indicates that the site was not used at night, i.e., it was not a domestic site.[28]

Moreover, the structure itself becomes inexplicable as a farmstead—unless, as Rainey suggests, it was a watchtower to protect the family. It cannot be a family home because it has no entrance, and both rooms were filled with ashes and animal bones.

In short, despite the fact that the structure is most unusual, Zertal’s theory is the simplest explanation for the structure; it fits well what we know about some ancient Israelite altars from the Bible and later Jewish texts.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

December 18, 2018

|

Last Updated

February 3, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Zvi Koenigsberg worked alongside the late Prof. Adam Zertal throughout the Ebal excavations (1982-88). His long-term mentors include the late Prof. Benjamin Mazar and Prof. Yair Zakovitch. Koenigsberg wrote The Lost Temple of Israel, Academic Studies Press, Boston, 2015. Questions welcome at zvi@thelosttemple.com.

Essays on Related Topics: