Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Why Are Laws for Priests Included in the Torah?

Leviticus folio, Xanten Bible, written and illustrated by Joseph ben Kalonymus ha-Nakdan, of Xanten, Germany 1294. The New York Public Library

Priestly Laws

The book of Leviticus, along with the laws about the sanctuary (the “Tabernacle”) in Exodus and the laws in Numbers, all belong to the sections of the Torah that critical scholars assign to the Priestly Source (“P”), the largest of the four main sources of the Torah. The laws primarily concern the sacrifices, the priests, ritual purity and impurity, Sabbath and holy days and the Tabernacle. Because these all involve the priests in one way or another, the rabbis called Leviticus Torat Kohanim, “The Instructions pertaining to the Priests.”[1]

The opening verse, however, addresses the Israelites as a whole:

ויקרא א:א וַיִּקְרָא אֶל מֹשֶׁה וַיְדַבֵּר יְ-הוָה אֵלָיו מֵאֹהֶל מוֹעֵד לֵאמֹר. א:ב דַּבֵּר אֶל בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל וְאָמַרְתָּ אֲלֵהֶם...

Lev 1:1 YHWH called to Moses and spoke to him from the Tent of Meeting, saying: 1:2 Speak to the Israelite people, and say to them…

Many of the laws in Leviticus contain information that the people need, such as the kinds of animals they may sacrifice, the situations requiring expiatory sacrifices, and the dates of the festivals. But a number of the laws are addressed specifically to the priests since these laws concern technical and sometimes intricate procedures that they perform, such as what they are to do with sacrifices after receiving them from donors, with diagnosing “leprosy,” and with bodily defects that would disqualify them from officiating.[2]

The public at large would have little use for these laws and might not even understand much of their terminology. Yet even these laws became part of the Torah,[3] which is regularly read aloud in the synagogue to all Jews without distinction.

Making Priestly Laws Public

Why are such laws part of the Torah? One clue seems to be found in Leviticus 21, a chapter that is addressed to the priests:

ויקרא כא:א וַיֹּאמֶר יְ-הוָה אֶל מֹשֶׁה אֱמֹר אֶל הַכֹּהֲנִים בְּנֵי אַהֲרֹן

Lev 21:1 YHWH said to Moses: “Speak to the priests, the sons of Aaron, and say to them…”

The chapter requires the priests to avoid actions and bodily defects that would disqualify them from officiating. Surprisingly, the final verse of the chapter, after repeating its opening statement that addresses it to the priests, adds that it was addressed to the people as well:

ויקרא כא:כד וַיְדַבֵּר מֹשֶׁה אֶל אַהֲרֹן וְאֶל בָּנָיו וְאֶל כָּל בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל.

Lev 21:24 Thus Moses spoke to Aaron and his sons and to all the Israelites.

As Prof. Jacob Milgrom z”l pointed out, Moses seems to be informing the people of the rules incumbent on priests in order to put the people in a position to make sure that the priests comply.[4] This enables us to view this chapter, and all the priestly laws, in the larger context of the Torah’s instructions to make all of its laws public.

Making the laws public not only informs the people of their own duties but also of the duties of public officials (priests and prophets, judges and kings), including the limits that God placed on the officials’ rights (especially in Deut. 16:18-18:22). As Professor Moshe Greenberg z”l pointed out, this lays the ground for public scrutiny and criticism of the officials and prevents them from gaining the absolute authority and prestige that they would command by controlling important information known only to them.

Knowledge of these limitations empowers citizens to resist and protest abuses of authority. Prophets in particular exercised this power to admonish kings, officials and priests as well as the people for moral and religious sins.

Vernacular Bibles

That this effect is not merely theoretical is shown by what happened in medieval Europe when the Bible was made available to the public by the publication of vernacular translations in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries:

Once the people were free to interpret the Word of God according to the light of their own understanding, they began to question the authority of their inherited institutions, both religious and secular, which led to reformation within the Church, and to the rise of constitutional government in England and the end of the divine right of kings.[5]

A Well-Informed Public as a Torah Value

Enabling the citizens to judge leaders’ actions is but one aspect of the Torah’s goal of creating a public well informed about God’s laws. The goal itself reflects the very raison d’etre of the Israelite people, as indicated by God’s reason for choosing Abraham and his descendants:

בראשית יח:יט כִּי יְדַעְתִּיו לְמַעַן אֲשֶׁר יְצַוֶּה אֶת בָּנָיו וְאֶת בֵּיתוֹ אַחֲרָיו וְשָׁמְרוּ דֶּרֶךְ יְ-הוָה לַעֲשׂוֹת צְדָקָה וּמִשְׁפָּט...

Gen 18:19 For I have singled him out, that he may instruct his children and his posterity to keep the way of YHWH by doing what is just and right…

For the nation “to keep the way of YHWH by doing what is just and right” requires the people to know what is just and right. Efforts to teach the laws to the entire people begin at Mount Sinai. God addressed the Ten Commandments to the entire people. He then gave Moses the laws of the Book of the Covenant, commanding him:

שמות כא:א וְאֵלֶּה הַמִּשְׁפָּטִים אֲשֶׁר תָּשִׂים לִפְנֵיהֶם.

Exod 21:1 These are the rules that you shall set before them.

When Moses came down from the mountain he repeated the laws to the people, wrote them down, and then read them to the people again (Exodus 24:1-7). God then told Moses to return to the mountain to receive

שמות כד:יב אֶת לֻחֹת הָאֶבֶן וְהַתּוֹרָה וְהַמִּצְוָה אֲשֶׁר כָּתַבְתִּי לְהוֹרֹתָם.

Exod 24:12 [T]he stone tablets with the teachings and commandments which I have inscribed to instruct them.

Deuteronomy and Teaching Torah

The book of Deuteronomy systematizes these beginnings and develops them much further. Moses exhorts the people to learn God’s Torah (תורה, literally “Teaching”), to discuss it constantly, and to teach it to their children as a guide for their lives (see Deuteronomy 4:9-10; 5:1; 6:6-9, 20-25; 11:18-20), and he writes it down and provides for reading it to the entire people every seven years (31:9-13) so

דברים לא:יב לְמַעַן יִשְׁמְעוּ וּלְמַעַן יִלְמְדוּ וְיָרְאוּ אֶת יְ-הוָה אֱלֹהֵיכֶם וְשָׁמְרוּ לַעֲשׂוֹת אֶת כָּל דִּבְרֵי הַתּוֹרָה הַזֹּאת.

Deut 31:12 That they may hear and so learn to revere YHWH your God and to observe faithfully every word of this Torah

These exhortations embody Deuteronomy's profound concern to impress the Torah on the mind of all Israelites, not only in order to inform them of the contents of the laws but to shape their character as individuals and as a nation. This concern is one of the most characteristic and far-reaching ideas of the Bible, particularly of Deuteronomy.[6]

All Jews Are Well-versed in the Torah: Josephus

The practice of teaching the laws to the entire citizenry is unusual. This was recognized by Josephus in his proud description Judaism:

For ignorance [Moses] left no pretext. He appointed the Law [=the Torah] to be the most excellent and necessary form of instruction, ordaining… that every week people should desert their other occupations and assemble to listen to the Law and to obtain a thorough and accurate knowledge of it, a practice which all other legislators seem to have neglected.

Indeed, most people, far from living in accordance with their own laws, hardly know what they are... But, should anyone of our nation be questioned about the laws, he would repeat them all the more readily than his own name. The result, then, of our thorough grounding in the laws... is that we have them, as it were, engraven on our souls. A transgressor is a rarity; evasion of punishment by excuses an impossibility.[7]

Despite his hyperbole, Josephus accurately described the Torah's aim. Since Israel's primary duty to God is obedience to His laws, teaching them to every Israelite is imperative, and this is Moses's main aim in Deuteronomy.

Torah Frescos in Dura Europos

This aspect of biblical religion was expressed artistically in frescoes of the third century CE at Dura Europos in Syria, as perceived by Elias J. Bickermann:

The sacred books of all other religions...were ritual texts to be used or recited by priests. In the Mithra temple at Dura it is a Magian in his sacred dress who keeps the sacred scroll closed in his hand. [But] in the synagogue of Dura a layman, without any sign of office, is represented reading the open scroll.[8]

Consequences of Educated Public

The education of the entire public in priestly as well as civil laws had far-reaching consequences in Judaism.

Democratization of Torah Leadership

Among other things, it led to the democratization of religious leadership. Expertise in religion did not remain confined to the hereditary priesthood, and it became possible for any Jew, irrespective of family background, who had the intellectual qualifications to master it. This is the significance of the fact that in the long run rabbis rather than priests became the religious leaders in Rabbinic Judaism.[9]

Pervasive Torah Study by Non-Specialists

In addition, the idea that the entire people must be instructed in God's law eventually led to the intellectualization of Judaism. The principle that the study of Torah (talmud Torah) is equal, if not superior, to all other commandments is based on the recognition that study of Torah is the prerequisite to their performance, since it alone leads to all the others (m. Pe’ah 1:1).

אֵלּוּ דְבָרִים שֶׁאָדָם אוֹכֵל פֵּרוֹתֵיהֶן בָּעוֹלָם הַזֶּה וְהַקֶּרֶן קַיֶּמֶת לוֹ לָעוֹלָם הַבָּא. כִּבּוּד אָב וָאֵם, וּגְמִילוּת חֲסָדִים, וַהֲבָאַת שָׁלוֹם בֵּין אָדָם לַחֲבֵרוֹ, וְתַלְמוּד תּוֹרָה כְּנֶגֶד כֻּלָּם:

These are things the fruits of which a man enjoys in this world, while the principal remains for him in the World to Come: Honoring one's father and mother, acts of kindness, and bringing peace between a man and his fellow. But the study of Torah is equal to them all.[10]

The ideal of a learned laity is beautifully expressed in Abraham Joshua Heschel's moving eulogy for East European Jewry, The Earth is the Lord's. Heschel makes the following observation:

A Christian scholar who visited Warsaw during the First World War, wrote of a remarkable experience he had there: "Once I noticed a great many coaches on a parking-place, but with no drivers in sight. In my own country I would have known where to look for them. A young Jewish boy showed me the way: in a courtyard, on the second floor, was the shtibl of the Jewish drivers. It consisted of two rooms: one filled with Talmud-volumes, the other a room for prayer. All the drivers were engaged in fervent study and religious discussion...It was then that I found out...that all professions, the bakers, the butchers, the shoemakers, etc., have their own shtibl in the Jewish district; and every free moment which can be taken off from their work is given to the study of the Torah. And when they get together in intimate groups, one urges the other: 'Sog mir a shtickl Torah -- Tell me a little Torah.'"[11]

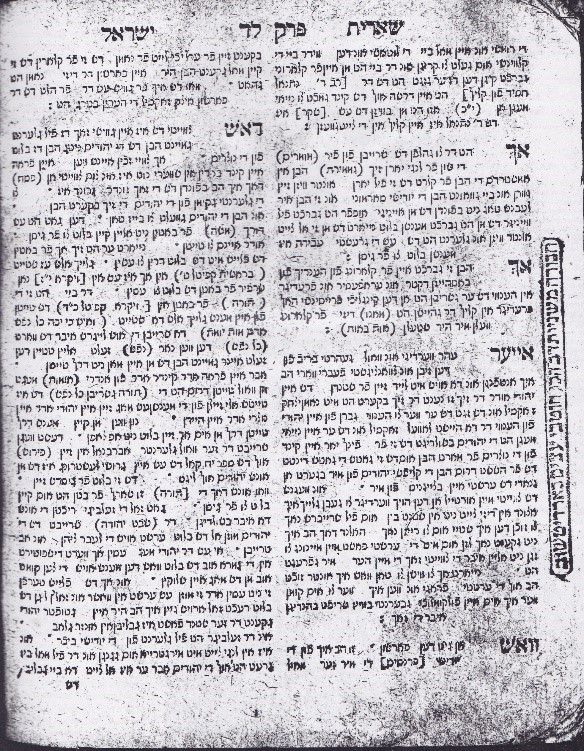

To illustrate the Christian scholar's observation, Heschel called attention to a Yiddish book that was sent, after the Holocaust, from Yivo’s Library in Vilna to its library in New York. Its subject is Jewish history, but the remarkable thing about it is the stamp in its margin. It reads:

חבורה משניות דב'הכנ חוטבי עצים בארדיטשוב

(Property of) the Mishna study Group of the Woodchoppers’ Synagogue of Berditchev.

This illustrates that even in the synagogue of one of the humblest professions, members gathered to study the Mishna.[12]

Study as a Religious Necessity: The Story of Hillel and the Proselyte

This focus on law as the core of Jewish learning was encapsulated by Rabbi Louis Finkelstein in his apt characterization of Judaism as "a religion which expects each adherent to develop judicial qualities."[13] This characterization captures the message of the famous story about Hillel who was addressed by a would-be proselyte, who offered to become a Jew if Hillel could recite the entire Torah while his questioner stood on one foot. Hillel responded by paraphrasing the Torah’s exhortation, “Love your fellow as yourself” (וְאָהַבְתָּ לְרֵעֲךָ כָּמוֹךָ; Lev 18:18) as follows (b. Shabbat 31a):

דעלך סני לחברך לא תעביד

Whatever is hateful to you, do not do to others.[14]

And he added:

זו היא כל התורה כולה, ואידך - פירושה הוא, זיל גמור.

This is the entire Torah, the rest is its explanation: Go and study!

In his commentary on the Talmudic passage, Rashi explains:

שאר דברי תורה פירושה דהא מילתא הוא, לדעת איזה דבר שנאוי זיל גמור ותדע

The rest of the Torah is the interpretation of this dictum: In order to know what is hateful, go and study (it) and you will know.

What Hillel meant is that love is not enough. Friendship and good intentions are not an unambiguous guide to proper behavior. That can only be learned by studying the complexities of human relations as they are dealt with in the Torah and its commentaries.

Even this cannot possibly anticipate every situation, but inculcating judicial qualities – skill in ethical decision-making – prepares every Jewish person to deal with unanticipated ethical dilemmas in a way that is consistent with Jewish values.

The Ideal of a Learned Citizenship

Viewed in this light we can see that sharing all of God’s laws, even the minutiae of priestly laws, with the public at large was part of the Torah’s larger program of creating a citizenry that knows its own duties and its rights, including the limits on the rights of public officials.

On the individual level, too, the need to learn God’s laws in order to observe and apply them made the textual study of Torah an ideal for each and every Jew. These goals exemplify ideals for citizenship and for personal life that are worth pursuing today no less than in the past.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

March 12, 2018

|

Last Updated

January 17, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Rabbi Jeffrey Tigay is Emeritus Ellis Professor of Hebrew and Semitic Languages and Literatures at the University of Pennsylvania. He has his Ph.D. from Yale, and his M.H.L and ordination from JTS. He is the author of the Jewish Study Bible commentary on Exodus and the JPS commentary on Deuteronomy, a revised Hebrew edition of which will be published in the Mikra LeYisrael series. He is currently writing a commentary on Exodus for the same series.

Essays on Related Topics: