Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Shavuot: How the Festival of Harvest Grew

Shavuot enters the stage as a festival in celebration of the grain harvest. In contrast with Pesach and Sukkot, the Torah does not link it to any particular episode of the exodus from Egypt.

The Torah’s Name for the Holiday

In Exodus (23:16), the holiday is called חג הקציר hag ha-qatzir “the harvest feast”; the verse further clarifies that the harvest is of “the first-fruits of your labors, of what you sowed in the field.” Exodus 34:22 echoes this. In Leviticus (Leviticus 23:15-22), no name is given; 50 days after the Omer offering that signals the beginning of the harvest a “new offering” of two loaves, accompanied by animal sacrifices, is to be made. In Numbers (28:26-31), it is יום הבכורים yom ha-bikkurim “the day of first-fruits,” and further regulations for sacrifices are given.

Deuteronomy calls it חג שבועות hag Shavuot, “feast of weeks,” for the simple reason that you have to count seven weeks to get to it from “when you put the sickle to the standing grain” – presumably the “day after the Sabbath” of Leviticus 23:15. Deuteronomy adds that the Israelites must give thanks to God for the harvest of their land, attend to the needs of the poor, and remember that they were once slaves in Egypt (Deut 16:10-12).

Unlike Pesach and Sukkot, Shavuot is not mentioned in Tanakh outside the five books of the Torah, with the single exception of 2 Chron 8:13.

The Sages’ Name for the Holiday

When Shavuot figures in our prayers we call it זמן מתן תורתנו – “the time our Torah was given,” a phrase of which the earliest record we have is the Seder Rav Amram, a 9th century Gaon of Sura. The gift of Torah is certainly an occasion for joy and celebration, but the Torah never calls the festival by this name nor anything like it. Even the Mishna doesn’t connect Shavuot with Torah.

The Rabbis themselves, when they have something to say about Shavuot, call it not z’man mattan toratenu, but עצרת atzeret. This term is doubly curious, as the Torah uses the term atzeret only for the last day of Pesach (Dt 16:8) and for Shemini Atzeret (Lev 23:36; Num 29:35; Nehemiah 8:18; 2 Chron 7:9). Nor does the Mishna (Megilla 3:5) specify the Decalogue (Ten Commandments) as the reading for Shavuot, though it is now the universal Jewish custom; and it actually bans (Megilla 4:10) the public reading of Ezekiel’s Chariot, our haftara for the day, though Rabbi Judah demurs and the halakha was subsequently decided in his favor.

Does the Torah Indicate When the Revelation at Sinai Occurred?

How, then, did the first-fruits festival become the festival of the Revelation of Torah? Can we determine a date for the giving of the Torah and does that date coincide with Shavuot? Some say that Torah was revealed “roll by roll” (b. Gittin 60a), rather than complete at Mount Sinai, and if that was so there would be no single date for the whole. All agree, however, that the Covenant with Israel was made and the Decalogue was proclaimed to the assembled nation at Mount Sinai/Horeb on one single, momentous day. But when, exactly, was this supposed to have happened?

Here is how the Sages reconstruct the date: “In the third month after the Israelites left Egypt they arrived in the Sinai desert” (Exodus 19:1). As they left Egypt on 15 Nissan it follows that they arrive in Sinai some time in Sivan. From the specific ביום הזה bayom hazeh “on that very day,” with the definite article, the rabbis infer that they arrived on the first day of the month, Rosh Ḥodesh Sivan.

Next, Moses ascends to receive instructions and is told that the people should be kept off the mountain and should purify themselves for three days in preparation for hearing the divine word. Thus, allowing time for Moses to ascend, return, fence off the mountain and instruct the people, plus the days of purification and his initiative (according to Rabbi Yosé) in “adding a day,” this brings us to the sixth or seventh of Sivan. Was this 50 days counting from 16 Nisan, i.e., Shavuot? That depends on whether Nisan, Iyar, or both that year had 29 or 30 days.[1]

When Did Shavuot Become Celebration of the Giving of the Torah?

Given that this coincidence of dates between Shavuot and the giving of the Torah is uncertain, and never explicit in the Torah, how did the first-fruits festival come to be so intimately linked with the revelation of Torah? We can search for hints in “external” sources from ancient times.

Tobit and 2 Maccabees

Two Apocryphal books (Tobit 2:1; 2 Maccabees 12:32) mention Shavuot, which they call by its Greek name Pentecost (πεντηκοστύς pentēkostus “fifty”), because it is fixed as the fiftieth day of the Omer, with no mention of Torah.

Philo

Philo, writing early in the first century C.E, when the Temple still stood, enthuses about the number 50 (=32 + 42 + 52) which he claims confers great significance on the festival. The second day of Pesach, he explains, the “day of the sheaf,” marks the beginning of the harvest, which continues until Shavuot when, in a final act of gratitude, thanks are rendered to God for the harvest not only of the land of Israel but of the whole world (Special Laws 1:179, 183).

As Philo puts it:

Within the feast [of Pesach] there is another feast following directly after the first day. This is called ‘The Sheaf,’ a name given to it from the ceremony which consists in bringing to the altar a sheaf as a first-fruit, both of the land which has been given to the nation to dwell in, and of the whole earth, so that it serves that purpose both to the nation in particular and for the whole human race in general” (Special Laws 1:162, trans. F. H. Colson).

Elsewhere (On the Contemplative Life, #75) Philo describes a wonderful ceremony, replete with Torah discourses and even an all-night vigil (#83), held on Shavuot by an ascetic Jewish sect he calls Therapeutae (“healers”), but there is no explicit link with the event of mattan Torah.

Jubilees

The Book of Jubilees, written before 150 BCE, provides the earliest and clearest hint. This book, now found in collections of Pseudepigrapha, is considered canonical by the Ethiopian Jews, Bete Israel, who call it by its Ge’ez name Mets’hafe Kufale (“Book of Division”). In Chapter 6 the author describes how Noah emerged from Ark on “the new moon of the third month” (i.e. Sivan) and, after making atonement by suitable offerings, established a new Covenant with God. This was to be an “eternal covenant,” and was observed by the Patriarchs but forgotten by their descendants until renewed at Mount Sinai: “One day in the year in this month they shall celebrate the festival. For it is the feast of weeks and the feast of first fruits” (6:21). Clearly, the author sees Mattan Torah itself as a renewal of Noah’s eternal covenant, and associated with Shavuot, though he stops short of actually renaming the festival.

Dead Sea Scrolls

The Dead Sea Scrolls, which include many copies of Jubilees may give another clue. Both the Rule of the Community and the Damascus Document describe at length a ceremony of Renewal of the Covenant by which an acolyte was accepted into the Qumran community; this is a re-enactment of the Covenant at Sinai, with fulsome commitment to Torah. Some scholars, the late Geza Vermes among them, have claimed that the ceremony took place annually on Shavuot. If it could be proved that this was so (I have not seen convincing evidence that it was) it would demonstrate the association of Shavuot with mattan Torah well before the time of the rabbis. The Qumran community, like the Sadducees, celebrated Shavuot 50 days from the Sunday after Pesach, which in their fixed calendar always worked out on Sunday 15 Sivan, so if they thought the Torah was given on Shavuot, they would have calculated the date differently from the rabbis.

Book of Acts

The only other ancient document to throw some light on the relationship is the New Testament, where Acts 2 describes how the disciples gathered on Shavuot (Pentecost), were seized by a “holy spirit” and were inspired to speak in different languages (this is why “Pentecostals,” who practice glossolalia—speaking in foreign/invented tongues—are so called). This makes sense if we read it as a claim for a new revelation, taking the place of the Sinai revelation, and occurring on the same auspicious date in the calendar.

Absence in the Mishna

Despite the implications from a number of the above sources that some Jews were associating Shavuot with mattan Torah before the time of the Mishna, surprisingly, the Mishna itself ignores the association. Perhaps the Rabbis were reluctant to stray from the meaning the Torah attaches to the festival, or perhaps they were wary of endorsing an interpretation that had gained currency among sects they regarded as heretical.

A century ago, Rabbi Yeḥiel Mikhal Halevi Epstein (Arukh haShulḥan OH 494:2) suggested that since the Torah is eternal, there is no way it could be tied to a specific date in the way that, e.g., the Exodus itself is tied to Pesach. From the more limited perspective of the people, however, the date on which they received it was significant.

The Associations of Shavuot with Mattan Torah

As the liturgy took shape and urbanization and exile reduced the prominence of the harvests of the land of Israel in the life of the Jewish people, the association between Shavuot and mattan Torah took root and was firmly validated. The Torah readings and haftarot associated with revelation and the reading of the book of Ruth, who according to the rabbis accepted the Torah, became fixed. Poets compiled Azharot, poetic versions of the 613 commandments, to be recited on Shavuot, further consolidating the message that Shavuot, even though it could no longer be celebrated with first-fruit processions to the Temple in Jerusalem, was fit and well as z’man mattan toratenu

Minhagei Shavuot through the Ages

Shavuot still had a long way to go to become the festival we know and love. Over the centuries new customs emerged. R. Moshe Isserles (רמ״א gloss on SA OH 494:3) mentions a custom of eating dairy dishes and then meat dishes on Shavuot; this is nowadays uncommon, but many Jews follow the custom of serving dairy dishes, including cheesecakes of distinctive local varieties. In many places this is the day young children are introduced to the learning of Torah with special ceremonies and treats.

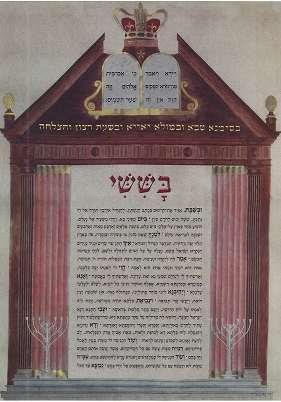

In North Africa, ketubot (marriage documents) are read celebrating the “espousal” of Israel by God, a metaphor familiar from commentaries on Shir haShirim. A friend from Gibraltar tells me that at Shaḥarit on the first day, when the Ark is opened, Gibraltarians read the ketuba composed by Rabbi David Kimḥi, and at Minḥathe azharot of Ibn Gabirol and Judah Halevi. Also, they make hamotsí over matza shemura on the first night “to fulfil the opinion that holds that Pesach to Shavuot is one ḥag with 49 days of Ḥol Hamoed.” In line with the agricultural significance of the festival, synagogues everywhere are festooned with flowers and, especially among Zionists, first-fruit presentation ceremonies take place.

The Origin of the Tikkun

One of the greatest innovations was introduced by sixteenth-century mystics anxious to carry forward the theme of Shavuot as a festival of divine revelation, a theme already exploited in the Zohar (Emor 98a), which mentions that “pious ones of old” would stay awake all night in anticipation of the revelation. The poet Solomon Alkabetz, in his introduction to the spiritual diary Maggid Mesharim left behind by Rabbi Joseph Karo (author of the Shulḥan Arukh), recounts a mystical experience he shared with Karo and their circle one Shavuot ca. 1530 in Turkey, before they made their way to the Holy Land and settled in Safed. They were held in thrall by a heavenly voice – the Mishna personified – which spoke through Karo; for the two days and nights of the festival they did not sleep, but rejoiced in the constant revelation of Torah, though grieving at the lament of the Shekhina in exile.

Karo’s all-night vigil was emulated in elite mystical circles and through the combined influence of Hasidism and the yeshiva movement has now become popular. People stay up all night to learn, re-enacting receiving the Torah at Sinai. Some follow the set Order of Service, known as tiqqun leil Shavuot, which includes the whole Book of Deuteronomy, but most nowadays prefer to devise their own programs of lectures and study sessions interspersed with refreshments.

Conclusion

Shavuot as celebrated by Jews around the world is a superb demonstration of the way in which the “divine commandment” can take root among the people and acquire rich new levels of meaning. At first, a simple thanksgiving celebration at the conclusion of the grain harvest, it absorbed over the centuries the idea of renewal of the covenant at Sinai, elaborated this with mystical insights and popular custom and inspired poets and philosophers to new creation. Finally, with the establishment of Israel, the holiday renewed its connection with the land. What we now celebrate, in a myriad of local variations, is a “harvest” not only of produce of the land, but of the produce of the spirit of Torah and the Jewish people.

What better day to think deeply on the meaning of “Torah from Heaven”!

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

May 26, 2014

|

Last Updated

November 26, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Rabbi Norman Solomon was a Fellow (retired) in Modern Jewish Thought at the Oxford Centre for Hebrew and Jewish Studies. He remains a member of Wolfson College and the Oxford University Teaching and Research Unit in Hebrew and Jewish Studies. He was ordained at Jews’ College and did his Ph.D. at the University of Manchester. Solomon has served as rabbi to a number of Orthodox Congregations in England and is a Past President of the British Association for Jewish Studies. He is the author of Torah from Heaven.

Essays on Related Topics: