Edit article

Edit articleSeries

A Torah-Prescribed Liturgy: The Declaration of the First Fruits

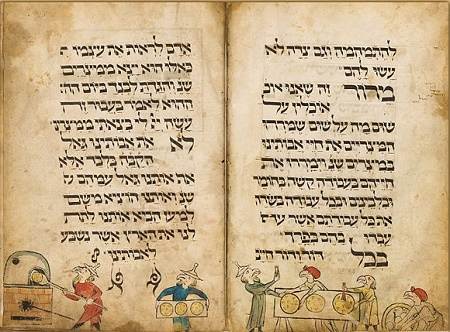

Bikkurim – The First Fruits. yoramraanan.com ©

Alongside the hierarchical worship of God, mediated by the priests, Levites, and other leadership, the Tanakh contains numerous appeals or prayers to God by private individuals.[1] Such prayers naturally are often spontaneous and intended for recitation on a single occasion alone.[2]

The Torah, however, provides two examples where individual, ordinary Israelites (presumably male) are required to recite a liturgical text. Both examples appear in Deut 26 in Parashat Ki Tavo:

- The declaration of the first fruits (vv. 1-11).

- The disclosure of the tithe (vv. 12–15).[3]

Here I focus on the offering of the first fruits in the Torah and in later rabbinic literature.

I. Phenomenological

Double Alienation

The declaration of the first fruits is a bold text. The context of the passage in Deuteronomy, as part of Moses’ address to the Israelites on the plains of Moab, calls upon the Israelites wandering in the wilderness with no permanent ties to the earth to imagine themselves as farmers securely living in their own land. But simultaneously, the text demands of (future) farmers living in their own land that they remember their days as wanderers in the wilderness—and necessarily as well ponder the fragility of their own lives.[4] Each audience, the imagined audience of the wilderness and the intended audience in the land, are at a remove from the text; in academic parlance, the text contains a double alienation.[5]

II. Historical

The History of the People becomes Personal

One might have expected the declaration of the first fruits to include an expression of gratitude for crops and an entreaty for future produce, as in similar ceremonies in other world cultures, but the text discusses only Israelite history and the involvement of the divine. The farmer declares before the priest:

דברים כו:ג הִגַּדְתִּי הַיּוֹם לַה’ אֱלֹהֶיךָ כִּי בָאתִי אֶל הָאָרֶץ אֲשֶׁר נִשְׁבַּע ה’ לַאֲבֹתֵינוּ לָתֶת לָנוּ.

Deut 26:3 I acknowledge this day before the Eternal your God that I have entered the land that The Eternal swore to our fathers to assign us.

With these words, farmers on pilgrimage, who have traveled from villages far and near, personally experience Israelite history. In every passing generation, the farmer must conceive of himself, if for a fleeting moment, as a nomad without a land. The rehearsal of this less-than-glorious history is intended, among other things, to deter hubris on the part of the landowner.

The farmer then proceeds to an account of national history, beginning with the statement that “arami oved avi [6] (אֲרַמִּי אֹבֵד אָבִי),”continuing with the suffering of the Israelites under Egyptian bondage and eventual redemption, and finally, dramatically, arriving in the here and now, standing as a farmer with his basket of produce before the priest. [7] The entire recapitulation of national history comes to a calculated climax in the moment when the farmer comes bearing the first fruits of the land bestowed upon him.

The declaration ends with:

דברים כו:י וְעַתָּה הִנֵּה הֵבֵאתִי אֶת רֵאשִׁית פְּרִי הָאֲדָמָה אֲשֶׁר נָתַתָּה לִּי ה’.

Deut 26:10 Wherefore I now bring the first fruits of the soil which You, Eternal, have given me.

By concluding the story of Israelite history with these words, the farmer breaks the fourth wall, himself stepping out of the narrative as its ultimate culmination, and in fact, its fulfillment.

Becoming the Climax of One’s National Story

Not only does the individual present his personal story as irretrievably enmeshed with that of the nation, but he tells this national story as emphatically his own – the national becomes the personal, the historic becomes the biographic. This mode of portrayal evokes the requirement on the night of the Seder to recount the story of the exodus:

בכל דור חייב אדם לראות את עצמו כאילו הוא יצא ממצרים.

In every generation, one must see oneself as if he came out of Egypt.[8]

In Deuteronomy 26, the dynamic is even more complex than of Passover. The farmer who recites the declaration of the first fruits is the active character, and the last, appearing in the plot, directed in no uncertain terms to view himself as the beneficiary of God, who brought him to this land. He says not, “You brought my ancestors to the land,” but “I came to the land (בָאתִי אֶל-הָאָרֶץ)” (v. 3). The account of national history invites the individual personally to experience the arrival in the Land of Israel and to speak in behalf of the entire nation, present and past.

The narrative deals with the passing on of the historic memory. Put differently, this is a text whose main purpose is the transmission of the text itself, ensuring its perpetuation in future years.[9]

Reciting the declaration of the first fruits year in and year out, the farmer teaches himself that the final chapter in the national story is unfolding in real time, as he stands with his first fruits opposite the priest in the Temple. This statement, thus, is more powerful than the call in the Haggadah for those present to view themselves “as if” they had departed Egypt, in that the farmer holding his produce is exhorted literally to see himself as having personally come to the land.[10]

Buber – Literary Connection between the Farmer and the Israelites Entering the Land

Martin Buber comments that,

The phrase with which the commandment is addressed to Israel, “when you come to the land” is paralleled by the statement “I came to the land.” Even a member of a latter-day generation speaks in the name of that bygone generation that arrived in Canaan, and accordingly in the name of the entire nation across the generations, which arrived in Canaan in the body of that generation.[11]

Every year the farmer bears witness to his personal privilege of being able to declare that “I came to the land.” The experience of bringing the first fruits, especially the declaration, attests to this miracle. The bringing of the nation to the land and the bringing of the first fruits are mutually linked, as linguistically expressed by the use of a single root ב-ו-א six times in the pericope.[12] As Buber notes, the farmer is unable to give any of his produce, because the land and all that is in it belong to God, who alone can make gifts of them. All the farmer can do is bring a part of the crop with which he has been graced by God.[13]

III. Anthropological

The Personal and the National

The bringing of the first fruits takes place when the farmer’s produce ripens. According to the Mishnah, this period is relatively a long one; it extends from Shavuot to Sukkot,[14] more than four months.

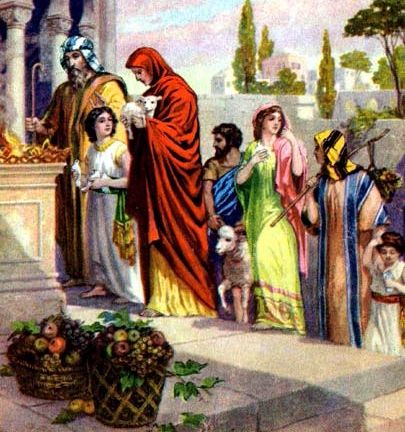

The commandment of the Torah is in the singular and evokes an image of the farmer standing opposite the priest in the Temple. The ceremony takes place adjacent to the altar, in the precincts of the Temple, a venue not typically frequented by Israelite laity (v. 4).[15]

דברים כו:ד וְלָקַח הַכֹּהֵן הַטֶּנֶא מִיָּדֶךָ וְהִנִּיחוֹ לִפְנֵי מִזְבַּח ה’ אֱלֹהֶיךָ.

Deut 26:4 he priest shall take the basket from your hand and set it down in front of the altar of the Eternal your God.

The agricultural act of bringing the first fruits is an experience in which one literally enters the sanctum.

Conversely, the Mishnah gives an eloquent, detailed, and lively account of the pilgrimage to Jerusalem and the bringing of the first fruits (bikkurim) as a dramatic public activity:

כיצד מעלין את הבכורים. כל העיירות שבמעמד. מתכנסות לעיר של מעמד. ולנין ברחובה של עיר. ולא היו נכנסין לבתים. ולמשכים היה הממונה אומר. קומו ונעלה ציון אל בית ה’ אלהינו:

How do they bring the bikkurim up [to Jerusalem]? All the cities of a Ma’amad [one of 24 regions, each of which sent in turn a delegation to the Temple to be present and represent the entire people at the public sacrifices] would go into [central] city of the Ma’amad and sleep in the streets of that city without going into the houses. When they arose, the supervisor would say, “Arise! Let us go up to Zion, to the house of the Lord our God!”

The personal obligation borne by the individual finds expression in the communal journey to the Temple. The description begins with the appearance outside Jerusalem of the people bringing their fruits, and their being greeted by the leadership and local artisans. Next, they proceed to Jerusalem as a group and finally arrive in the Temple, where each individual, from the king to the common farmer, stands opposite the priest. After the impressive public journey, the Mishna turns to the singular when depicting the farmer before the priest. (See appendix for the Mishna and translation.)

An Expression of Victor Turner’s Theory of Communitas

In the terminology of anthropologist Victor Turner, the joint pilgrimage may be designated a communitas—a compelling community-building experience divergent from the accustomed order that blurs the conventional balance of social power and thus permits participants to experience fraternity and equality in a way that would be impossible within the normal social structure.[16] The process poses an intriguing dialectic: the experience of traveling to the Temple is communal, yet the obligation applies to the individual, and the commandment is implemented in full only by the lone farmer. This dialectic is reflected in the recitation of a text in which he declares his belonging both the Israelite people and his part in their national experience.[17]

IV. Feminist

Presence and Absence: Distinguishing Between the Offering and the Declaration

The offering of the first fruits differs from other biblical offerings of the first of a given category in that it requires not only a donation, but an accompanying declaration.[18] Philo describes the ritual as follows:

For every one of those men who had lands and possessions, having filled vessels with every different species of fruit borne by fruit-bearing trees… brings with great joy the first fruits of his abundant crop into the temple, and standing in front of the altar gives the basket to the priest, uttering at the same time the very beautiful and admirable hymn prescribed for the occasion; and if he does not happen to remember it, he listens to it with all attention while the priest recites it.[19]

In this ceremony, all are equal. All as one, from the simple farmer to the king himself, grasp their baskets and stand before the priest. Yet is every person really included?

Rabbinic Interpretation: Women and Converts

The Rabbis distinguish between the requirement to bring the produce and reciting the declaration (m. Bikkurim 1:1):

יש מביאין בכורים וקורין מביאין ולא קורין ויש שאינן מביאין אלו שאינן מביאין.

There are those who bring first fruits and read, [there are] those who bring but do not read, and there are those who do not bring.

The rabbis determine who may make the declaration and who may not based on the relation of the individual to what is stated in the Torah.

Converts, for instance, bring first fruits, but omit the declaration due to their inability to say the words, “[the land] which the Eternal promised our fathers to give to us (אֲשֶׁר נִשְׁבַּע ה’ לַאֲבֹתֵינוּ לָתֶת לָנוּ),” because their ancestors were not Israelite.[20]

Although the Torah refers to the farmer only in masculine terms (as normally is the case), the Mishna does require women to bring first fruits, and includes them with converts among those “who bring but do not read.” Women are excluded since the Torah says, “which the Eternal gave me (‘אֲשֶׁר-נָתַתָּה לִּי ה)” (v. 5)” – and women were not originally allotted land in Israel.[21] Women then may participate in fulfilling the obligation to bring first fruits but not the parallel duty of reciting the declaration, with its purpose of inspiring contemplation and identification of personal biography with national history.[22]

Regrettable though this non-egalitarian stance may be, we would do poorly to forget the crucial fact that women had equal standing in their obligation to come to Jerusalem as pilgrims and bring their first fruits, appearing within the Temple before the priest and taking part in that sacred experience with all the other people of Israel. Counterintuitive though it may be, women in the time of the Temple seemingly enjoyed a more robust status and greater inclusion than in certain denominations of the present.[23]

The exclusion of converts from certain liturgical statements was voided as early as the Jerusalem Talmud, which was followed by the famed letter written by Maimonides to ‘Ovadiah the Convert: “You ought to say all [the prayers] as laid down; do not change anything.” With regard to the exclusion of women from religious practice, meanwhile, our forefathers (!) left frontiers yet to be explored and much work still to be done.

V. Liturgical

Ancient Texts Don’t Die

With the destruction of the Temple, the sacrifice of the first fruits was discontinued. The declaration of the first fruits, however, remained alive. It was revivified by the sages of the Mishnah, who embedded it in their Seder liturgy (m. Pesahim 10:4):

מתחיל בגנות ומסיים בשבח ודורש מארמי אובד אבי עד שיגמור כל הפרשה כולה:

He begins with ignominy and concludes with greatness, and he expounds from “arami oved avi” (Deut 26:5) until he finishes the entire pericope.

To be sure, the accustomed Haggadah text does not in fact include the entire passage, but suffices with the introduction, omitting the dramatic conclusion that gives meaning to the passage (Deut 26:9-10),

וַיְבִאֵנוּ אֶל הַמָּקוֹם הַזֶּה וַיִּתֶּן לָנוּ אֶת הָאָרֶץ הַזֹּאת אֶרֶץ זָבַת חָלָב וּדְבָשׁ. וְעַתָּה הִנֵּה הֵבֵאתִי אֶת רֵאשִׁית פְּרִי הָאֲדָמָה אֲשֶׁר נָתַתָּה לִּי ה’.

He brought us to this place and gave us this land, a land flowing with milk and honey. Wherefore I now bring the first fruits of the soil which You, O Eternal, have given me.”

The very reason for reciting the text, is absent from the Haggadah, which discusses the exodus from Egypt but breaks off before the arrival in the Land of Israel.

The fact that the Passover Haggadah was developed in the Diaspora and reflects Judaism that is not based on the land led the kibbutzim and some liberally inclined religious Jews to explicitly or implicitly reinstate the tradition of including the arrival in the Land of Israel in their Haggadot and Seder services.[24]

Declaring First Fruits on Yom HaAtzma’ut

The rejuvenation of the declaration of the first fruits has continued in our day. Some have adopted the practice of reading it at a ceremony or as part of a prayer service on Israeli Independence Day, without omission and in full awareness of the fact that it is predicated on “הַמָּקוֹם הַזֶּה” (“this place”) and הָאָרֶץ הַזֹּאת (“this land”). The choice to make this text part of the Independence Day liturgy, it would seem, expresses a wish to temper the words, “The Land of Israel was the birthplace of the Jewish people”—expressing that the nation was born and took form in the land, and omitting national development and Jewish life outside the land—with a more complex presentation of the relationship between nation and land, perhaps to bring completion to that opening line of the Declaration of Independence.

בארץ-ישראל קם העם היהודי,

In the land of Israel the Jewish people rose.

בה עוצבה דמותו הרוחנית, הדתית והמדינית,

In it, their spiritual, religious, and political identities were shaped.

בה חי חיי קוממיות ממלכתית,

In it, they lived a life of national independence.

בה יצר נכסי תרבות לאומיים וכלל-אנושיים,

In it were formed their cultural values, national and universal.

והוריש לעולם כולו את ספר הספרים הנצחי.

And it bequeathed to the world the eternal book of books.

The passage reflects the fact that we are home now but acknowledges both the process leading to this moment and the fact that the dwelling in the Land of Israel is not obvious or guaranteed.

We have come, then, full circle – from the nomads reflecting on the days when they will be farmers thinking about the sojourn in the wilderness, to the citizens of the State of Israel, reflecting on ancient and recent history, the fragile miracle of the ingathering of exiles, and the re-establishment of Jewish life in the Land of Israel.

Appendix

Ritual of Bringing the First Fruits (m. Bikkurim3:2-6)

ג:ב כיצד מעלין את הבכורים…

3:2 How do they bring up the first fruits […]

ג:גהקרובים מביאים התאנים והענבים והרחוקים מביאים גרוגרות וצמוקים והשור הולך לפניהם וקרניו מצופות זהב ועטרת של זית בראשו החליל מכה לפניהם עד שמגיעים קרוב לירושלם.

3:3 Those who are near bring [fresh] figs and grapes, and those who are far bring dried figs and raisins, and the bull walks before them, its horns overlayed with gold and an olive garland on its head, and the flute plays before them until they arrive near Jerusalem.

הגיעו קרוב לירושלם שלחו לפניהם ועטרו את בכוריהם.

Once they had arrived near Jerusalem, they would send [a herald] before them and adorn their first fruits.

הפחות הסגנים והגזברים יוצאים לקראתם לפי כבוד הנכנסים היו יוצאים וכל בעלי אומניות שבירושלם עומדים לפניהם ושואלין בשלומם אחינו אנשי המקום פלוני באתם לשלום:

The governors, lieutenants, and treasurers would go out to meet them; according to the rand of the entrants they [would determine who] went out [to greet them]. All the craftsmen in Jerusalem would stand before them and inquire of their welfare: “Our brothers, men of such-and-such place, have you come in peace?”

ג:ד החליל מכה לפניהם עד שמגיעין להר הבית. הגיעו להר הבית אפילו אגריפס המלך נוטל הסל על כתפו ונכנס עד שמגיע לעזרה….

3:4 The flute plays before them until they arrive at the Temple Mount. Once they have arrived at the Temple Mount, even King Agrippa takes the basket on his shoulder and enters inward until he arrives in the courtyard […]

ג:ו עודהו הסל על כתפו קורא מהגדתי היום לה’ אלהיך (דברים כו) עד שגומר כל הפרשה ר’ יהודה אומר עד ארמי אובד אבי הגיע לארמי אובד אבי מוריד הסל מעל כתפו ואוחזו בשפתותיו וכהן מניח ידו תחתיו ומניפו וקורא מארמי אובד אבי עד שהוא גומר כל הפרשה ומניחו בצד המזבח והשתחוה ויצא:

3:6 With the basket still on his shoulder, he recites from “I acknowledge this day before the LORD your God” (Deut. 26:3) until he finishes the entire pericope. Rabbi Yehudah says: When he comes to “arami ovad avi“, he lowers the basket from his shoulder and holds it by its brim, and the priest places his hand beneath it and waives it, [25] and he recites from “arami ovad avi” until he finishes the entire pericope. He would place it aside the altar, and prostrate himself and exit.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

September 16, 2016

|

Last Updated

November 11, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Rabbi Dalia Marx is Professor of Liturgy and Midrash at Hebrew Union College-JIR (Jerusalem). She earned her Ph.D. at the Hebrew University and her rabbinic ordination at HUC-JIR (Jerusalem and Cincinnati). Among her publications are When I Sleep and When I Wake: On Prayers between Dusk and Dawn and A Feminist Commentary of the Babylonian Talmud. Her website is: www.dalia-marx.com.

Essays on Related Topics: