Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Of Jars, Scraps, and Scrolls: How Ancient Books Were Composed

Replicas of the clay jars containing the Dead Sea Scrolls, Israel Museum. Wikimedia

Some form of very basic literacy may have been part of Israelite/Judean society from early on, as we can see various examples in both kingdoms of writing that is not royal in character, whether in the Gezer calendar, the Samarian ostraca, the inscriptions in Kuntillat Ajrud, or the Siloam Inscription, to name a few.[1] Given that widespread education did not come about until the Hellenistic period, basic literacy was made possible by their having possessed a concise alphabet that was easily manageable and did not require the highly specialized scribal education of the cuneiform system.[2]

When writing brief messages, such as receipts, ancient Israelites commonly used pottery shards (ostraca), which were ubiquitous, had a smooth surface, and could be washed off and reused.[3] Additional writing materials were stones, palm leaves, small pieces of papyrus sheets, rolled or folded, or even just scraps.[4] Notably, the Bible never describes such forms of writing. Instead, we only hear about more elite forms of writing in connection with prophets, kings, and their use of specialized scribes.

For example, YHWH commands Moses to come to the top of the mountain to receive the laws of the covenant carved onto stone tablets by YHWH’s own hand.[5] The material of the tablets stands out, as writing tablets, luchot, were normally made of wood, and thus not durable long term.[6] Carving words in stone, in contrast, was the most durable form of writing in the ancient world.[7]

Following the Covenant Collection, Moses first delivers YHWH’s laws orally and the people accept them. Then he writes them down upon a ספר, “scroll” and reads it to the people again for them to accept it.[8] Scrolls also appear as artifacts in prophetic visions. Ezekiel receives a message from God together with a scroll of lamentation that he is commanded to eat.[9] We are never even informed what the scroll said. Similarly, Zechariah sees a giant flying scroll in one of his visions,[10] and we aren’t told specifically what it says.

The material envisioned in all these texts is animal hide, a “fancy” and expensive material,[11] not the papyrus scraps, pottery sherds, wooden slats, or even parchment scraps, that would have been the norm for the average person who would not be purchasing or preparing special writing materials.

Putting Together Books from Scraps

Storage containers, such as the jars in which the Qumran documents—in this case actual scrolls—were used for writing meant to be preserved. Indeed, specific types of jars were even crafted for the storage of documents.[12] If we envision that specific jars were designated for certain texts—psalms, proverbs, Mosaic, etc.— we can understand how this practice contributed to the composition of biblical books.

The Book of the Twelve

Take The Twelve Minor Prophets. What connects these works and makes them into one book? The obvious answer is that they are short; many could have been written entirely on short scraps of papyrus. The fact that they ended up as part of a book centuries later implies that they must have been stored together, perhaps in a jar collecting small prophetic works.

Deutero-Zechariah

Scholars have long noted that the book of Zechariah is an artificial combination of two different prophets.[13] The first eight chapters are associated with the prophet Zechariah from the beginning of the Second Temple period, and chapters 9–12, generally referred to as Deutero-Zechariah, from a different prophet whose style and message is easy to distinguish from that of Zechariah.

Apparently, a piece of prophetic text with no name attached to it was included in the collection jar from which the Book of the Twelve was composed, and the scribes who put it together added this collection of prophecies to Zechariah, for whatever reason, as they wished to present all prophecies as deriving from a named prophet.[14]

Deutero-Isaiah and Trito-Isaiah

This may well be the same reason we have the large book of Isaiah, made up of at least three prophetic works, the eighth century prophet Isaiah, the exilic prophet known as Deutero-Isaiah, and the early Second Temple period prophecies of Trito-Isaiah. (These latter two are not names of real individuals; both collections were anonymous and appended to the eighth century Isaiah son of Amoz.)

Jeremiah: Two Versions

Nathan Mastnjak suggests a more complex example: The latter half of the book of Jeremiah is organized very differently in the Greek LXX—which likely derives from a Hebrew Vorlage—and in the Hebrew MT. For example, in MT chapters 46–51 contain a section known as Jeremiah’s oracles against the nations; in LXX, this collection appears in chapters 25–31. It contains the same prophecies, more or less, against the same nine nations, but in a different order:

MT: Egypt, Philistia, Moab, Ammon, Edom, Damascus, Kedar, Elam, Babylon

LXX: Elam, Egypt, Babylon, Philistia,[15] Edom, Ammon, Kedar, Moab.

The breakdown is as follows:

Egypt: MT ch. 46; LXX ch. 26

Philistia: MT ch. 47; LXX ch. 29 (vv. 1–7)

Moab: MT ch. 48; LXX ch. 31

Ammon: MT ch. 49 (vv. 1–6); LXX ch. 30 (vv. 1–5)

Edom: MT ch. 49 (vv. 7–22); LXX ch. 29 (vv. 8–23)

Damascus: MT ch. 49 (vv. 23–27); LXX ch. 30 (vv. 12–16)

Kedar: MT ch. 49 (vv. 28–34); LXX ch. 30 (vv. 6–11)

Elam: MT ch. 49 (vv. 34–39); LXX ch. 25 (vv. 14–19)

Babylon: MT ch. 50–51; LXX ch. 27–28

While it is possible that one version is revising the other, it seems likely that both the MT and the Hebrew Vorlage of the Greek LXX editors were working from the same storage unit.[16]

“This Is the Torah of…”

Leviticus has a series of laws about sacrifice and purity that begin or end with the phrase זאת תורת “this is the teaching of.” While some scholars argue that this is just the editor’s way of organizing the material, Israel Knohl of Hebrew University has suggested that these passages in the Priestly text of the Torah began as instructions, kept on papyrus or small scraps of parchment, filed in the Jerusalem Temple, that priests could use as reference or refreshers when performing these rituals.[17]

Pentateuch and Psalms

On a larger scale, the Torah/Pentateuch and the book of Psalms were too long to have been combined in a single scroll until the third century C.E., well after they were conceptualized as a unit. It was the very storage in—and hence grouping of texts by—jars and other containers such as baskets or the Roman capsa that made it possible to refer to them as a sefer, a literary unit, even though the Torah consisted of five individual books.[18]

Storing scrolls and other pieces of writing material in containers contributed to the categorization, standardization, and ultimately canonization of a set of scrolls and other materials as a unit with subunits (book 1, book 2...); it did not impede, but, rather, encouraged, additions, especially in the formative stages of a text-compound.[19]

From Scraps to Scrolls

Ancient book production underwent significant technological change and improvement in the Hellenistic period when the Ptolemies of Egypt made collecting Greek poetry and literature the basis of their claim to be Alexander’s rightful heirs.[20] According to legend, the invention of parchment followed the Ptolemies’ pursuit of amassing Greek texts in the library of Alexandria by borrowing and copying them—the endeavor that led to the translation of the Septuagint—papyrus was no longer be exported to the Seleucids, who worked on a similar project in Pergamon.[21] The shortage in papyrus resulted in an investment in the refinement of animal hide by the Pergamene, who ultimately refined parchment (in German: Pergament).

Finer parchment made scrolls less bulky and allowed for the combination of multiple books into a single scroll. In the third century C.E., the production of a scroll containing the five books of Moses became technologically feasible, and rabbinic sages began to regulate how such Torah scrolls should be written.[22] The rules concerning the proper writing of such scrolls were collected in the post-talmudic tractate, called soferim [scribes]. Refined parchment could ultimately also be used for the codex, a Roman era invention of folding papyrus sheets into quires that were stitched together[23]—the origin of books as we now know them.

Roman and Rabbinic Slips

The study of textual materiality in the emerging Judaism and Christianity of the first centuries C.E. tends to focus on the question of why the Christians seemed to prefer the codex while the Jews stuck to the scroll format for their sacred texts. In this debate, everyday writing materials such as wooden slats, scraps of papyrus, and ostraca have been swept under the carpet.[24]

Keeping these other materials in mind, however, helps to explain why Late Antique literature is the way it is, broken down into small parts, sentences, short stories, parables. They corresponded to the considerably small writing surfaces on which they were composed and transmitted.

Such literal pieces of wisdom also permeate rabbinic literature.[25] Indeed, while Rabbinic literature is inclined to portray the earlier rabbis as transmitting knowledge fresh from the teacher’s mouth to the student’s ear, it nevertheless mentions quite a few writing materials en passant.

Sending Messages to the Study House

The Babylonian Talmud, for example, relates a story in which the Rabbis Meir and Nathan attempt a coup against Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel through a humiliating tactic. After he narrowly avoids falling into the trap, he has them temporarily banned from the study house, but they send messages to their fellow rabbis on pitqi (sg. pitqa), a Greek loan word that Michael Sokoloff translates as “slip”:[26]

בבלי הוריות יג: פקיד ואפקינהו מבי מדרשא הוו כתבי קושייתא [בפתקי][27] ושדו התם דהוה מיפריק מיפריק דלא הוו מיפריק כתבי פירוקי ושדו.

b. Horayot 13b He commanded that they be removed from the study house. They would write their analytical problems [on scraps] and throw them [into the study house]. Those that were answered were answered. Those that were not answered, [Rabbis Meir and Nathan] would write answers and throw them [into the study house].

In their comprehensive Greek lexicon, Henry George Liddell and Robert Scott render the Greek pittakion also as referring to tablet, label, ticket.[28] The materiality of the pitqi is nowhere specified, but from the story, it was clearly lightweight enough to be thrown. Other texts describe them as being shot by an arrow (b. Sanh. 26a), falling from the sky (b. Baba Metzia 86a; b. Sanhedrin 64a; b. Yoma 69b), or worn as a pendant around the neck (b. Qidd. 73b).

From the Scroll (back) to the Slip

The pitqi stories, fictional though they may be, give an idea of the writing materials on which rabbinic maxims and legal statements were likely to have been collected. But there is also evidence that longer compositions, probably on papyrus scrolls, were cut up into short units and were then used associatively in the Babylonian Talmud.

This seems to be the case with those medical recipes that follow the standard terminology “For [name of the disease] bring …”. This formulation occurs at least 47 times in the Babylonian Talmud and is also known from Greek treatises on such simple remedies.[29]

בבלי גיטין סט: לכאב מיעי לייתי תלת[30] מאה[31] פלפלי אריכתא וכל יומא נישתי מאה[32] מיניהו בחמימי רבין[33] דמן נרש[34] עבד לברתיה דרב אשי[35] מאה וחמשין מהני דידן ואיתסי .

b. Gittin 69b For pain in the intestines: Bring three hundred long peppers and drink one hundred of them every day in hot water. Rabin of Narash made one hundred and fifty from these for Rav Ashi’s daughter, and she recovered.

The standard formulation allowed readers to quickly grasp the beginning of a new recipe as well as its therapy or alternative therapies, introduced by “and if not” (ואי לא). The distribution of this particular type of recipe and its use—sometimes placed into the mouth of a rabbi as a saying, sometimes anonymously—points to the compilation techniques at work in the compilation process of the Babylonian Talmud and, indeed in late antique literature more generally: small units were puzzled together to form a whole that could be dismantled again if necessary.

A Woven Tapestry

Just as the biblical books discussed above, rabbinic texts may also have begun as bits and pieces of different sizes, gathered in jars and other containers that formed the rabbinic archive. Indeed, both the Talmuds and the Midrashim continuously surprise through the scope of their commentaries, their eclectic nature, and their digressions: features that can be explained through their origins in jars and baskets full of individual but associatively related pieces of text.

Rabbinic texts refer to oral transmission, but such transmission need not be limited to literal “Torah from the mouth,” i.e., knowledge contained only in the memory of tradents.[36] Instead, we can understand this phrase as a shorthand reference to the difference between the formal and highly regulated production of the written Torah and informal note-taking such as writing on scraps.[37] Such notes, stored together in jars, would end up as a key part of the Talmudic textual tapestry—the Latin textus as well as the Hebrew massekhet literally mean “fabric”—woven together to create the rich and complex dialogue style familiar to us.

According to this model, the commentaries on Mishnaic lemmas were constructed as follows in the Babylonian Talmud: Bits and pieces of material were collected and sorted according to keywords. These keywords were then assigned to Mishnaic lemmas that themselves followed pre-existing lists of words that required explanations (scholia). These may also have furnished some of the keywords, but the composers of the Babylonian Talmud clearly also kept an eye on the way the parallel passages in the older Jerusalem Talmud were arranged.[38]

The redactors would then arrange the material in an engaging order, following, in principle, the ancient rhetorical structure for speeches that consists of introduction, narration of the case, the proofs and the peroration/epilogue.[39] Editorial questions and comments from the unnamed Talmudic voice—the stam—connect the pieces and give, together with the attributions, the impression of an ongoing dialogue. This method of composition has parallels in Greek and Latin texts that imitate the conversations held at a symposium, such as Athenaeus’ Learned Banqueters or Macrobius Saturnalia.[40]

The Rabbinic Pinqas and Latin Pinax

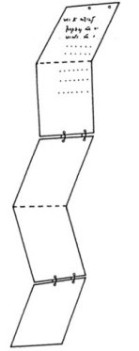

An in-between stage, after the scraps and small tablets, but before the full literary expression of a commentary on a Mishnaic lemma as we now have them, may have been pinax (plural pinakes)—what the rabbis call a פנקס (pinqas)—a folding, codex or concertina-like notebook, often made of wood slats bound together.[41] In the Roman world, it is the pinax that preceded the creation of full-fledged codices, and the same is likely true of rabbinic works such as the Talmud. Such a structure illustrates why Talmudic stories, even if they are lengthy, are episodic and divided into different scenes that each may have fit one slat.

Several references to pinqasim in rabbinic literature give us a flavor for the presence of this technology among the rabbis. For instance, the Talmud compares the way a fetus rests in its mother’s womb to a folded pinqas:

בבלי נדה ל: דרש רבי שמלאי: "למה הולד דומה במעי אמו? לפינקס שמקופל ומונח. ידיו על שתי צדעיו, שתי אציליו על ב' ארכובותיו, וב' עקביו על ב' עגבותיו, וראשו מונח לו בין [ירכיו][42]..."

b. Niddah 30b Rabbi Simlai expounded: “To what may a fetus in its mother’s womb be compared? To a pinax that is folded up and put away. Its hands are against its temples, its two arms against its two knees, its two heels against its two buttocks, and its head between its thighs…”[43]

Another reference to a pinax appears in a story in which a series of men come and share their dreams with a Samaritan dream interpreter and R. Ishmael son of R. Yossi, who compete over the dream’s interpretation:

איכה רבה (בובר) פרשה א אתא אוחרנן לגביה. א[מר] ל[יה]: "חמית בחלמי טעין פנקס, ואית ביה עשרים וארבעה לוחין, ואנא כתיב מן הכא, ומחיק מן הכא."

Lamentations Rabbah, Parashah §1 Another man came before [the dream interpreter]. He said to him: “I saw in my dream that I was carrying a pinax with 24 slats, and I was writing on one side and erasing on the other.”[44]

א[מר] ל[יה]: "את סליק לרבו והוי עסקך רב, ואת הוי כתיב מן הכא, ומחיק מן הכא."

[The dream interpreter] said to him: “You will rise to greatness and have plenty of business, and you will write on one side and erase on the other (=so you can write more).”[45]

Taking Stock of Textual Materiality

Every text in antiquity comes with a body; its words have substance, possibly even flesh, if written on animal-skin.[46] A cow’s skin can be made into an Esther scroll and a belt, maybe even a pair of shoes to wear to the synagogue on Purim. The fact that writing materials were organic, and especially in the case of leather, had a history and needed special treatment such as oiling, led ancient Jews—and ancient societies more generally—to treat respective texts as objects with a certain agency, as being vulnerable or sensual, even as interfering, as righteous and sinful.[47]

But also the ostracon (sherd) used to write down the wedding contract[48] could have been from a vessel from which the grandparents drank on their wedding day and that had served the family for many years in that function before it broke by accident.[49] The wooden tablets, the ostraca, the stone, the leather rotulus (horizontal scroll) all bear marks of their prior life that interfere in the layout of the text, in its presentation.

The contemporary digitization of texts makes it difficult for us to appreciate the significance of the writing material and its storage in ancient times.[50] Since the advent of the printing press, books have been mass produced in identical format. And most writing, nowadays, is typed into a computer and stored digitally, with no materiality at all, and stored on the cloud.

Ancient writing culture was very different. It demanded physical work, and it created an artifact. Texts were therefore cherished as artefacts, safely stored, and sometimes borrowed, exchanged, or traded.[51] Notes, corrections, and remarks were added to texts. Sometimes a portion or all of it was wiped or scratched off in favor of another text. Well-protected, written texts could outlive several generations; but they could also rot or remain only partially preserved.[52] The way in which texts were stored affected the way in which they were eventually combined into scrolls or books as that technology developed. It is this material reality that the reader of modern editions of ancient books must keep in mind in order to understand their structure and texture.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

February 19, 2025

|

Last Updated

December 25, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Monika Amsler is Senior Research Assistant at the University of Bern’s Department of Ancient History and the Classical Tradition. She holds a Ph.D. from the University of Zurich, and is the author of The Babylonian Talmud and Late Antique Book Culture (Cambridge, 2023), and the editor of Knowledge Construction in Late Antiquity (Berlin, 2023).

Essays on Related Topics: