Edit article

Edit articleSeries

What Kind of Creatures Are the Cherubim?

Cherubim (detail) YoramRaanan.com ©

The centerpiece of a typical temple in the ancient world was a statue of a god. The tabernacle (משכן) is different in that it does not have such a statue. What it does have are two golden statues of cherubim (כרובים) who spread their wings over the kapporet, the lid of the ark of the testimony (Exodus 25:18–20 ≈ 37:7–9). Above the kapporet from between these two cherubim, YHWH meets with Moshe and speaks to him (Exodus 25:22 ≈ Numbers 7:89; cf. Leviticus 16:2).

The impression given by Exodus, that cherubim played a central role in the earliest stage of Judaism, is reinforced by references to cherubim elsewhere in the Tanakh:

- Statues of cherubim, of a somewhat different form, also spread their wings over the ark in the Jerusalem temple (1 Kings 6:23–28 ≈ 2 Chronicles 3:10–13; 1 Kings 8:6, 7 ≈ 2 Chronicles 5:7, 8; 1 Chronicles 28:18).

- Two-dimensional representations of cherubim decorate surfaces of the tabernacle (Exodus 26:1 = 36:8, 26:31 = 36:35) and the temple (1 Kings 6:29, 32, 35; 7:29, 36; Ezekiel 41:18, 20, 25; 2 Chronicles 3:7, 14).

- Living cherubim are associated with the Garden of Eden (Genesis 3:24; Ezekiel 28:14, 16)

- They are, apparently, described as being with YHWH as something he rides or sits upon (2 Samuel 22:11 ≈ Psalms 18:11; Ezekiel 9:3; 10:1–22; 11:22).

- Cherubim constitute a component in an epithet of YHWH which can be translated provisionally as “the cherubim sitter” or “the cherubim dweller”:[1] י(ו)שב הכר(ו)בים / ישב כרובים (1 Samuel 4:4; 2 Samuel 6:2 ≈ 1 Chronicles 13:6; 2 Kings 19:15 ≈ Isaiah 37,16; Psalms 80:2; 99:1).

What, specifically, is a cherub? In other words, what form or forms of creatures does the word כרוב designate?[2]

Winged Child

The first recorded attempt to identify the form of the cherub was made by the amora R. Abbahu of Caesarea (ca. 279–320), who employed a midrashic reading of כרוב as כרביא, which can be translated from Aramaic as “like a lad,” to assert that the cherub resembles a child (b. Ḥagigah 13b, Sukkah 5b). However, the cherubim are said to have wings (Exodus 25:20 = 37:9; 1 Kings 6:24, 27 ≈ 2 Chronicles 3:11–13; 1 Kings 8:6–7 = 2 Chronicles 5:7–8), and winged children are not attested in the iconography of the Land of Israel in the biblical period.

This identification is likely prompted by the erotes and cupids, the oft-winged boys that personified amorousness in the Greco-Roman art of R. Abbahu’s time. This conclusion can also explain the existence of several peculiar talmudic homilies attributing an erotic aspect to the cherubim of the Jerusalem temple (b. Yoma 54a–b).

Winged Adult

An anonymous sage in Midrash Hagadol asserted that the cherub resembles a human in all respects except that it has the wings of a bird; the anonymous exegete, unlike R. Abbahu, did not specify an age and presumably had in mind an adult.[3] This view was endorsed in part by Radak (ca. 1160–1235) and Ralbag (1288–1344).[4] The identification of cherubim as winged humans, whether adults or children, found early expression in Jewish and Christian visual art. For example, an illuminated Hebrew manuscript from northern France, dated to 1277–1286, shows the tabernacle ark cherubim as childlike creatures with six wings each, as influenced by Isa 6:2 [Figure 1].

It is now known that the winged adult human is a common denizen of ancient Near Eastern iconography, and several modern scholars have identified the cherub with it, including Carl F. Keil and Franz Delitzsch, Robert Pfeiffer, and Louis-Hugues Vincent.[5]

Bird

Rashbam (ca. 1085–1158) and Hizkuni (thirteenth century) stated that cherubim are birds.[6] This identification enjoys visual expression in a fifteenth-century drawing by the prolific Jewish illuminator Joel b. Simeon Feibush showing the biblical ark surmounted by two pigeon-like birds [Figure 2]. In the modern era, François Lenormant expressed the same idea regarding the tabernacle ark cherubim, writing that they were probably birds fashioned in the Egyptian artistic style.[7]

Human-Headed Birds

An intermediate position between this view and the preceding one was taken by Abraham b. Moses Maimonides (1186–1237), who suggested that the ark cherubim in the tabernacle had human heads and faces and avian wings, bodies and feet. He admitted the speculative nature of the suggestion and adduced no arguments in its favor.[8]

Winged Bovine

Rashbam’s student Joseph Bekhor Shor (second half of the twelfth century), whose name means “firstborn of an ox” – coincidence? – along with Isaac of Vienna (ca. 1180–1250) and other tosafists, proffered the view that typical cherubim are “angels in the image of oxen.”[9] Later scholars, such as the seventeenth-century Protestant polymath Hugo Grotius, promoted similar views.[10] One reason for this suggestion is the fact that the word “שור” in Ezekiel 1:10 is replaced by “כרוב” in Ezekiel 10:14, implying the terms are synonymous.

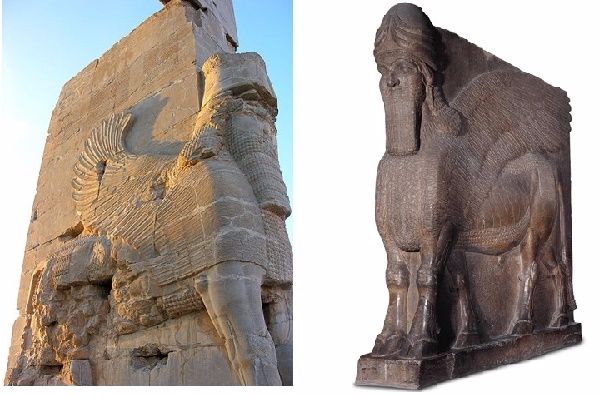

By the end of the eighteenth century, material evidence was adduced to support these views: the human-headed winged bull colossi of Persepolis, which were known from a drawing and description by Dutch traveler Cornelis de Bruyn [Figure 3].[11] Later, the publicity received by colossal human-headed winged bulls in Assyrian palaces excavated in the mid-nineteenth century [Figure 4], along with the mistaken belief that the Akkadian words kirûbu[12] or kāribu[13] designated these beings, boosted the view that cherubim shared the form of these colossi.[14]

Griffin

Doubting the association of the cherub with the human-headed winged bull, the nineteenth-century biblicist August Dillmann preferred to connect the cherub with the griffin, or raptor-headed winged lion.[15] The griffin appears in ancient Levantine iconography; for example, on a thirteenth-century B.C.E. ivory plaque from Megiddo [Figure 5].

Winged Sphinx

The prevailing opinion in current scholarship is that the cherub is a winged sphinx, i.e., a human-headed winged lion, such as that depicted on the sarcophagus of the late second-millennium B.C.E. Phoenician king Ahiram [Figure 6].[16] However, numerous indications found in the descriptions of the sculpted cherubim over the ark (Exodus 25:18–20 = 37:7–9; 1 Kings 6:23–26) reveal that their authors presupposed upright creatures.[17]

Evidence that the Cherubs Stand Upright

Sheltering with Wings - In the tabernacle, the ark cherubim are described as facing each other and “sheltering the kapporet with their wings” (Exodus 25:20 = 37:9). As noted by Umberto Cassuto and Richard Barnett, if the cherubim stood on four feet, they would shelter the כַּפֹּרֶת with their bodies, not with their wings.[18]

Standing on the Edge - It can be added that the cherubim are said to be located on either “edge” (קצה) of the kapporet (ibid. 25:18–19 = 37:7–8). If they stood on four legs and their bodies stretched over the length of the kapporet, the word “edge” would be inappropriate.

Awkward Position for Four-Legged Creature - Moreover, the statement that the cherubim shelter the kapporet with their wings indicates that the wings are extended forward (toward the center of the kapporet), beyond their heads. No depiction of a creature standing on four legs with its wings extended in such an awkward and clumsy position can be found in ancient Near Eastern visual art.[19]

No Length Measurement - In the case of the ark cherubim in the temple, the biblical text notes their height and “width” (wingspan), but not their length (1 Kings 6:23–28). As argued by Otto Thenius and many subsequent scholars, this can only be understood if we assume that the cherubim are upright and therefore have no significant length.[20]

Wingspan Equal to Height - An additional indication that the temple ark cherubim are upright creatures is that they are described as possessing a wingspan, 10 cubits (1 Kings 6:24, 25; cf. 2 Chronicles 3:11–13), that equals their height, also 10 cubits (1 Kings 6:23, 26). Franz Landsberger noted that this proportion does not evoke animal forms.[21] Martin Metzger developed the argument in light of his investigation of composite creatures in the ancient Near East. He stated that a composite four-legged creature whose height when standing on its four feet is 10 cubits would have wings of 12–15 cubits each – a length significantly greater the 5 cubits specified in the Bible.[22]

The uprightness of the cherub precludes its identification with the winged sphinx, as well as the winged bovine and griffin, which are all non-upright, four-legged creatures.

Composite Creature

A final possibility, first proposed by the tenth-century Jewish grammarian Menahem ibn Saruq, is that כרוב simply means “figure.”[23] Abraham ibn Ezra (ca. 1090–1160s) later elaborated on this idea, stressing that in different contexts the word can refer to different types of creatures.[24] Ibn Saruq and Ibn Ezra follow an older tradition expressed in Targum Neofiti and Saadia b. Joseph Gaon, both of whom rendered the word כרבים in the descriptions of the tabernacle tapestries as “figures.”[25]

An entirely different view etymologically, but one which leads to a similar, generalized identification of the cherub, was expressed by the thirteenth-century tosafist Isaac b. Judah Halevi in his work Panah Raza. He explained the root כרב as carrying the meaning “mix.” Thus, he characterized the cherubim of Eden in Genesis as “angels in the form of demons” and argued that their name is a reflection of the fact that they contain a mixture of two species.[26] This identification seems essentially the same as what today would be called a composite or hybrid creature (German: Mischwesen).

Like the previously cited views, the understanding of כרוב as referring to composite creatures generally, or to a class thereof, has been revived in modern times. Contemporary scholars advocating this position rely on the existence of what they see as contradictory descriptions of cherubim within the Hebrew Bible.[27]

This view is challenged by the fact that the biblical writers usually neglect to specify the form of the cherub, even when specifying other details such as materials, position, and dimensions (Exodus 25:18–20 = 37:7–9; 1 Kings 6:23–28 ≈ 2 Chronicles 3:10–13). This omission indicates that there was assumed to be a typical form, with which the reader would be familiar.[28]

Winged Adult Revisited

I believe that the the anonymous sage in Midrash Hagadol was correct, and the cherubim are winged humans. Recall that the ark cherubim in the temple are described as having a wingspan that equals their height (1 Kings 6:23–26). Not only four-legged animals, but also upright creatures, whether real ones such as birds or fantastic ones such as winged snakes, would have to have comically short wings in order for their wingspan to be only as great as their height.

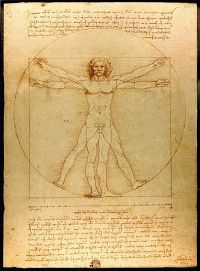

Indeed, we don’t find any depictions of these creatures in the iconographic record that have these proportions. Only humans, who stand erect on long legs and are by far the tallest of any of the candidates in proportion to their other dimensions, can have wings whose span equals their height that still look respectably long. Indeed, humans normally possess an arm-span that precisely equals their height. The Roman architect Vitruvius observed this fact long ago, writing in the context of proportionality in temples (De architectura 3.1.3):

If we measure the distance from the feet [of a man] to the top of the head, and we copy the measure to the outstretched arms, we find that the width equals the height, as with surfaces that are perfect squares.

This principle was famously illustrated in Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man drawing [Figure 7]. When depicting a winged human, it would make sense to portray the wings as having the length of arms.To be sure, winged humans in ancient Levantine iconography often have wings that are extravagantly long, far longer than their arms. But, as noted below, instances are known where the artist portrays the wings as being equivalent to arms and possessing the same length that the arms do (when they exist) or would (when they do not exist).

Illustrating Wings as Arms

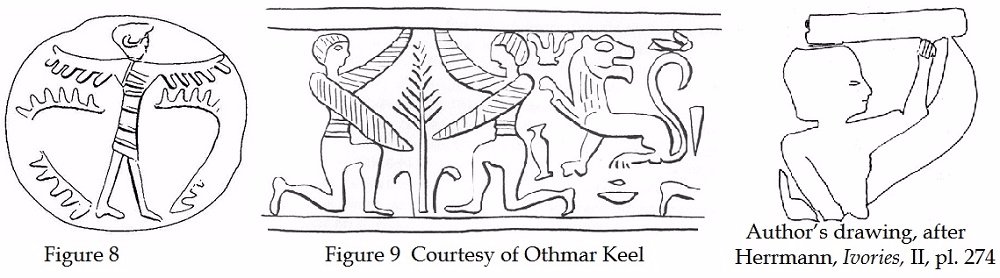

Three examples will suffice:

First, a stamp seal from Beth Shemesh, which, according to Keel, should probably be dated to ca. 1100–900 B.C.E., depicts an armless, winged human whose wings are spread straight out to his sides [Figure 8], like the ark cherubim in the temple (1 Kings 6:24–27 ≈ 2 Chronicles 3:11–13).[29]

Second, a cylinder seal from Tell el-Ajjul, in the vicinity of Gaza, dated by Teissier to the period of ca. 1820–1740, portrays a pair of armless, winged humans spreading their wings out in front of them, like the ark cherubim in the tabernacle, and sheltering a tree [Figure 9].[30]

Third, a fragmentary Phoenician openwork ivory found in Nimrud, probably from the ninth or eighth century B.C.E., shows a winged human with wings extended in the same position; the upper wing is preserved and is the same length as the adjacent arm [Figure 10].[31]

Conclusion – Winged Humans on the Ark

Thus, the author of the passage in Kings describing the temple ark cherubim could only have had winged humans in mind.[32] If so, we should regard it as probable that other biblical authors writing about cherubim did, too.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

February 7, 2016

|

Last Updated

December 17, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Raanan Eichler is an Associate Professor of Bible at Bar-Ilan University in Israel. He received his Ph.D. from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and completed fellowships at Harvard University and Tel Aviv University. He is the author of The Ark and the Cherubim (Mohr Siebeck, 2021) and many academic articles.

Essays on Related Topics: