Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Why Deuteronomy Has an Account of Aaron’s Death in the Wrong Place

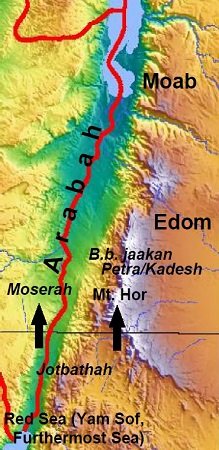

Mount Hor, now Jebel Harun (Mount of Aaron in Arabic), is on the left as seen from the Village of Taybe, itself just south of Petra (Kadesh). The top of Jebel Harun has two peaks; the white dot on the right peak is the mosque called “Welly,” which Muslims traditionally believe to be situated atop Aaron’s grave.

Deuteronomy is framed as a first person account from the perspective of Moses. Nevertheless, a number of redactional insertions, typically written in the third person, intrude into this first person address. This phenomenon was noted by ibn Ezra centuries ago.[1]

A Record of Aaron’s Death out of Context

Parashat Eikev contains one such especially problematic insertion, placed in between Moses’ description of God’s command to carve a second set of tablets and his description of God’s appointment of the Levites:

Carving the second tablets

י:א בָּעֵ֨ת הַהִ֜וא אָמַ֧ר יְ-הֹוָ֣ה אֵלַ֗י פְּסָל־לְךָ֞ שְׁנֵֽי־לוּחֹ֤ת אֲבָנִים֙ כָּרִ֣אשֹׁנִ֔ים וַעֲלֵ֥ה אֵלַ֖י הָהָ֑רָה… י:הוָאֵ֗פֶן וָֽאֵרֵד֙ מִן־הָהָ֔ר וָֽאָשִׂם֙ אֶת־הַלֻּחֹ֔ת בָּאָר֖וֹן אֲשֶׁ֣ר עָשִׂ֑יתִי וַיִּ֣הְיוּ שָׁ֔ם כַּאֲשֶׁ֥ר צִוַּ֖נִי יְ-הֹוָֽה:

10:1 At that time, Yhwh said to me, “Carve out two tablets of stone like the first, and come up to Me on the mountain… 10:5 Then I left and went down from the mountain, and I deposited the tablets in the ark that I had made, where they still are, as Yhwh had commanded me.

Itinerary plus death of Aaron

י:ו וּבְנֵ֣י יִשְׂרָאֵ֗ל נָֽסְע֛וּ מִבְּאֵרֹ֥ת בְּנֵי־יַעֲקָ֖ן מוֹסֵרָ֑ה שָׁ֣ם מֵ֤ת אַהֲרֹן֙ וַיִּקָּבֵ֣ר שָׁ֔ם וַיְכַהֵ֛ן אֶלְעָזָ֥ר בְּנ֖וֹ תַּחְתָּֽיו: י:זמִשָּׁ֥ם נָסְע֖וּ הַגֻּדְגֹּ֑דָה וּמִן הַגֻּדְגֹּ֣דָה יָטְבָ֔תָה אֶ֖רֶץ נַֽחֲלֵי מָֽיִם:

10:6 From Beerot-bene-yaakan the Israelites marched to Moserah. Aaron died there and was buried there; and his son Elazar became priest in his stead. 10:7 From there they marched to Gudgod, and from Gudgod to Yotbat, a region of running brooks.

Appointment of the Levites

י:ח בָּעֵ֣ת הַהִ֗וא הִבְדִּ֤יל יְ-הֹוָה֙ אֶת־שֵׁ֣בֶט הַלֵּוִ֔י לָשֵׂ֖את אֶת אֲר֣וֹן בְּרִית יְ-הֹוָ֑ה לַעֲמֹד֩ לִפְנֵ֨י יְ-הֹוָ֤ה לְשָֽׁרְתוֹ֙ וּלְבָרֵ֣ךְ בִּשְׁמ֔וֹ עַ֖ד הַיּ֥וֹם הַזֶּֽה….

10:8 At that time, Yhwh set apart the tribe of Levi to carry the Ark of Yhwh’s Covenant, to stand in attendance upon Yhwh, and to bless in His name, as is still the case….

Coming down the mountain to resume the march

י:י וְאָנֹכִ֞י עָמַ֣דְתִּי בָהָ֗ר כַּיָּמִים֙ הָרִ֣אשֹׁנִ֔ים אַרְבָּעִ֣ים י֔וֹם וְאַרְבָּעִ֖ים לָ֑יְלָה… י:יא וַיֹּ֤אמֶר יְ-הֹוָה֙ אֵלַ֔י ק֛וּם לֵ֥ךְ לְמַסַּ֖ע לִפְנֵ֣י הָעָ֑ם וְיָבֹ֙אוּ֙ וְיִֽירְשׁ֣וּ אֶת הָאָ֔רֶץ אֲשֶׁר נִשְׁבַּ֥עְתִּי לַאֲבֹתָ֖ם לָתֵ֥ת לָהֶֽם:

10:10 I had stayed on the mountain, as I did the first time, forty days and forty nights…. 10:11 And Yhwh said to me, “Up, resume the march at the head of the people, that they may go in and possess the land that I swore to their fathers to give them.”

The indented text (vv. 6-7) does not fit in the context for a number of reasons.

-

It shifts suddenly from first person (10:6) to third person (10:7-8).

-

The fragment interrupts the natural flow of the verses, which move from Moses going up the mountain (v. 1) and carving the Decalogue onto the new tablets (vv. 2-4), to the placement of the tablets in the Ark (v. 5), to the appointment of the Levites to carry the Ark (vv. 8-9), to Moses’ trip down the mountain (v. 10), and God’s command to head towards the Promised Land (v. 11)\

-

Most problematic of all, the Israelites are not in Beerot-bene-yaakan at this point in the story; they are at Horeb, waiting for Moses to come down with the tablets! Neither do they appear to be at Yotbat, since in verse 10 Moses and the people appear to be back at Horeb.

‘What is the Relevance of this Here?’ (Rashi on 10:6)

Indeed, Rashi is sensitive to the problematic text and expresses bewilderment:

מה עניין זה לכאן?

What is the relevance of this here?

To rephrase Rashi’s question from the perspective of a modern academic scholar, why did the redactor add this supplement here, and from where did he take it?

Rashi adds two more specific questions to the above:

ועוד, וכי מבארות בני יעקן נסעו למוסרה, והלא ממוסרות באו לבני יעקן…. ועוד, שם מת אהרן, והלא בהר ההר מת?

Moreover, did the Israelites travel from Bnei-yaakan to Moserah? Didn’t they come from Moserot (=Moserah) to Bnei-yaakan (Num 33:31)…? Moreover, is this where Aaron died? Didn’t he die on Mount Hor?

Rashi answers by claiming that Moses’ is speaking in hints here, since this is part of his rebuke, reminding them that after Aaron died in Mount Hor (not mentioned here) they backtracked all the way to Moserah, since they were afraid to fight the local inhabitants.[2] It is difficult to accept Rashi’s answer even as homiletics (derash), since nothing in the text suggests that this is a rebuke – it is a recitation of an itinerary. Rashi’s answer is really more like a throwing up of hands, but since Rashi could not make use of the methods of modern biblical scholarship, he had few (or no) options.

A Different Itinerary and Version of Aaron’s Death

Not a Redaction but an Itinerary Fragment

As mentioned above, Deuteronomy abounds with redactional supplements. Although a redactional supplement could be the work of a later redactor adding an explanatory gloss, that does not seem to be the case here. The supplement doesn’t relate to what comes before or after directly. Instead, the supplement appears to be a fragment from an itinerary list that a redactor cut from its original context and placed here. (Why here of all places I will suggest later on.)

The Itinerary: Deuteronomy Fragment vs. Numbers

As Rashi pointed out, the same itinerary list, though not in the same exact order, is found in Num 33:31–33.[3]

Deut 10 |

Num 33 |

| בְּאֵרֹ֥ת בְּנֵי־יַעֲקָ֖ן (Beerot-bene-yaakan) |

מֹסֵרֽוֹת (Moserot) |

| מוֹסֵרָ֑ה (Moserah) |

בְנֵ֥י יַעֲקָֽן (Bene-yaakan) |

| הַגֻּדְגֹּ֑דָה (Gudgod) |

חֹ֥ר הַגִּדְגָּֽד (Hor-haggidgad) |

| יָטְבָ֔תָה (Yotbatah) |

יָטְבָֽתָה (Yotbatah) |

Moreover, that list also mentions Aaron’s death, but there he dies in a different place (Num 33:37–39), Mt. Hor instead of Moserah.

Moreover, that list also mentions Aaron’s death, but there he dies in a different place (Num 33:37–39), Mt. Hor instead of Moserah.

The double death of Aaron is really more of a doublet than a contradiction. According to Numbers, Aaron is buried on Mt. Hor, less than a day south-west of Kadesh (Petra).[4]According to the Deuteronomy fragment, he climbs the mountain from the camp in Moserah, in the Arabah valley. A climb east from the Arabah could bring Aaron to the same mountain as is described in Numbers (though the walk would be several hours). (See Appendix 2 for details.)

Thus, although the itineraries in Deut 10:6–7 and Num 33:31–33 are similar to each other, and both include the death of Aaron in the general vicinity of the southern Transjordan, these passages did not come from the same quill.

Aaron’s Death in Numbers 33 – A Priestly Text

We can identify Numbers 33 as a Priestly text for a number of reasons:

- The date given in Numbers for Aaron’s death: “in the fortieth year after the Israelites had left the land of Egypt, on the first day of the fifth month” (Num 33:38b), is in characteristic P format.[5]

- The tradition that Aaron dies on Mount Hor is linked with the waters of Meribah story (Num 20:24; Deut 32:51). This narrative, based on its context, language, and perspective, belongs to P.[6]

In fact, the notation in Numbers 33 appears to be a shorthand reference to the longer Priestly account of Aaron’s death and Elazar’s ascension.

Numbers 20

וַֽיַּעֲלוּ֙ אֶל־הֹ֣ר הָהָ֔ר… וַיָּ֧מָת אַהֲרֹ֛ן שָׁ֖ם בְּרֹ֣אשׁ הָהָ֑ר

They ascended Mount Hor… and Aaron died there on the summit of the mountain.

Numbers 33

וַיַּעַל֩ אַהֲרֹ֨ן הַכֹּהֵ֜ן אֶל־הֹ֥ר הָהָ֛ר … וַיָּ֣מָת שָׁ֑ם

Aaron the priest ascended Mount Hor… and died there,

Thus, both accounts in Numbers stem from the Priestly source, but what about the fragment in Deuteronomy? Despite the fragment’s mention of Elazar the Priest, who is generally a Priestly character (he is never mentioned elsewhere in Deuteronomy),[7] we have already established that it could not be Priestly. From where does the fragment come?

A Fragment taken from E

I believe that it comes from the Elohist (E), mainly for the following reason: The North-South direction of the itinerary list fits with a particular storyline in Numbers and Judges, namely, the trip south to skirt the Edomite border. This storyline culminates in a battle with Sihon, king of the Amorites. (See Appendix 1 for the detailed argument.) Now, elsewhere I argued that the Sihon episode in Numbers—copied in Judges and modified in Deuteronomy—is part of the E source,[8] thus I suggest that the compiler took this fragment from E and placed it here.[9]

Why Place the Fragment in Deuteronomy (not Numbers)

Why did the compiler cut the E text and place it in Deuteronomy? The main impetus for this would seem to have been the doublet surrounding Aaron’s death. Each version (that of E and that of P) tells the story from the perspective of its own itinerary tradition, referencing where the Israelites were encamped when Aaron died (on Mount Hor or in Moserah in the Arabah valley).

Having the two accounts side by side would have required the compiler to create a story with two different camps (Mount Hor vs. Moserah) and two different routes, and, most likely, to come up with some explanatory glosses to explain this. It would also require deleting material from one of the versions, since Aaron can only die once. As the compiler decided to move the death scene, the itinerary list had to be moved as well, since the death scene is embedded in it.

In sum, the compiler of the Torah had two different narratives regarding Aaron’s death. Instead of trying to splice the two narratives together, the compiler left the P text unchanged, in its original place in the priestly continuum. But in order to preserve the E passage, he moved it from its original location, immediately after the confrontation at Kadesh (Num 20:14–21), to an appropriate spot in D.

Why Specifically Deuteronomy 10:6-7?

A number of elements in Deuteronomy 9-10 section may have attracted the eye of the compiler.

- Proximity to the mention of Aaron’s sin (Deut. 9:20). The traditional commentator Malbim noted the connection between this fragment and Aaron’s death and built his entire reading of these verses upon it (i.e., that this section hints at Aaron’s punishment really being on account of the Golden Calf and not only the Meribah story).[10]

- The appointment of the Levites (10:8-9). Aaron served as high priest and it is possible that the insertion wishes to imply that after Aaron’s death God sets up the new order: all Levites will now be priests (including but not exclusively Aaron’s son Elazar).[11]

- God’s command to Moses to start the march towards the land (10:11). – This verse is the last narration of Israel’s journey in Deuteronomy. From this point on, Moses sermonizes and gives laws. In other words, this is the only narrative text in Deuteronomy into which the compiler could have placed the itinerary fragment.

Thus, this topical association attracted this E passage to this spot in Deuteronomy—but a careful reading shows that it is secondary.

Afterword: Insights into the Compilation of the Torah

The compiler’s treatment of these E verses gives us some insights into his method.

- The compiler has great respect for his sources and tries to preserve as much of their text as possible, even if this means moving pieces around to avoid awkward contradictions.

- When the compiler combined J, E, and P, D was present alongside them, and it was to this document that he transferred data that was unsuitable for incorporation with the other sources.[12]

Thus, this exploration of Deuteronomy 10 offers additional support for the theory that the redaction of the Torah was done in a single phase, subsequent to the composition of all four core documents.

Appendix 1

Identifying the Source of the Fragment

A North-South Itinerary Fragment

As a geographer, I see one key to understanding this text in the toponyms: Beerot-bene-yaakan, Moserah, Gudgodah and Yotbatah. Luckily, we have a good idea where the first and last stops are located.

- Eusebius located Beeroth-bene-jaakan (Deut 10:6) about 10 miles west of Petra.[13]

- Yotbatah (10:7) is located farther south in the Arabah Valley.[14]

Noting the first and last stop, we have here an itinerary fragment going from north to south in the Arabah valley. The same appears to be true in the Priestly text, since it also contains a stretch where the Israelites travel from Bnei-yaakan to Yotbat.

Another itinerary that goes southwards in the Arabah appears in Deuteronomy proper (i.e., not in another redactional supplement) as well:

א:מו וַתֵּשְׁב֥וּ בְקָדֵ֖שׁ יָמִ֣ים רַבִּ֑ים כַּיָּמִ֖ים אֲשֶׁ֥ר יְשַׁבְתֶּֽם: ב:א וַנֵּ֜פֶן וַנִּסַּ֤ע הַמִּדְבָּ֙רָה֙ דֶּ֣רֶךְ יַם־ס֔וּף כַּאֲשֶׁ֛ר דִּבֶּ֥ר יְ-הֹוָ֖ה אֵלָ֑י וַנָּ֥סָב אֶת־הַר־שֵׂעִ֖יר יָמִ֥ים רַבִּֽים: ב:ב וַיֹּ֥אמֶר יְ-הֹוָ֖ה אֵלַ֥י לֵאמֹֽר: ב:ג רַב־לָכֶ֕ם סֹ֖ב אֶת־הָהָ֣ר הַזֶּ֑ה פְּנ֥וּ לָכֶ֖ם צָפֹֽנָה:

1:46 You dwelt in Kadesh a long time, like the days that you dwelt. 2:1 We marched back into the wilderness by the way of Yam Suf, as Yhwh had spoken to me, and skirted the hill country of Seir a long time. 2:2 Then Yhwh said to me: 2:3 You have been skirting this hill country long enough; now turn north.

According to 2:3, the Israelites were not travelling north till now, but skirting Edom in another direction, i.e. south. Since the Israelites are coming from Kadesh (Petra), and they are headed south, דרך ים סוף in verse 2:1 must mean a route going towards the Red Sea.[15]

Circumventing Edom

The southern route from Kadesh (Petra) is designed to skirt Seir, the homeland of the Edomites. The need to skirt the Edomite territory is referenced in two other places in the Bible, Numbers (the journey towards the land of Sihon) and Judges (Jephthah’s speech to the king of Ammon).

Num 21:4a

וַיִּסְע֞וּ מֵהֹ֤ר הָהָר֙ דֶּ֣רֶךְ יַם־ס֔וּף לִסְבֹ֖ב אֶת־אֶ֣רֶץ אֱד֑וֹם

They set out from Mount Hor by way of Yam Suf to skirt the land of Edom.

Judg 11:18a

וַיֵּ֣לֶךְ בַּמִּדְבָּ֗ר וַיָּ֜סָב אֶת־אֶ֤רֶץ אֱדוֹם֙ וְאֶת־אֶ֣רֶץ מוֹאָ֔ב

They traveled on through the wilderness, skirting the land of Edom and the land of Moab.

Why are the Israelites skirting Seir? According to Numbers (20:1-21) and Judges (11:1), the Edomites refuse them permission to enter their territory, so the Israelites are forced to circumvent Seir and get into the Cisjordan through a different route.

Entering Sihon’s Territory

According to all three sources, the Israelites end up in the wilderness east of Moab (Num 21:11b2–3; Deut 2:8b; Judg 11:18a2α), cross Wadi Arnon (Num 21:13; Deut 2:24 Judg 11:18a2β) north, and find themselves in Sihon’s territory. This leads to a battle and the conquest of the Amorite land (Num 21:21–25; Deut 2:26–36; Judg 11:19–22). As stated above (and argued in a previous piece), the battle with Sihon is part of the E source, and thus, most likely, so is this fragment.

North to South skirting of Edom as E: A Summary of the Argument

In short, the argument goes as follows:

- Deut 2:3 tells us that the Israelites travelled south in the Arabah.

- Thus, the skirting of Edom referenced immediately beforehand, in Deut 2:1, reflects a north to south route through the Arabah.

- This storyline, beginning with the skirting of Edom and ending with a war against Sihon, appears in three texts (Numbers, Deuteronomy, Judges). All three sources are working with (and modifying) one urtext.

- Having established in a previous piece that the Sihon story = E, we can assume that the urtext, including the north-to-south skirting of Edom account, is E.

- The Deuteronomy 10:6-7 fragment reflects a north-to-south route through the Arabah.

- This is the route around Edom, and is thus, the itinerary for E’s skirting of Edom account.

- This fragment was originally an integral part of the E source, and it came immediately after the Israelites’ stay in Kadesh.

Appendix 2

Where is Moserah?

Although historical geography has yet to pin down the toponym Moserah, I believe it is possible to uncover where it may have been in general. The Israelites are leaving Kadesh/Petra. Travelling east is not an option, since they are blocked from entering Edomite territory. This leaves only two ways out of Kadesh.

One route goes south-west via Mt. Hor to the Arabah. The other route goes north-west to the northern Arabah. As our itinerary (Deuteronomy 10:6-7) doesn’t mention Hor in its list of toponyms, it is likely picturing the north-west route, away from Mt. Hor.

Once in the Arabah valley, the itinerary fragment takes a north to south route (as described in appendix 1). Turning south in the Arabah, would bring the Israelites to the west of Mt. Hor. Thus, it is likely that both traditions picture Aaron’s burial plot in the same general vicinity.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

August 6, 2015

|

Last Updated

March 4, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. David Ben-Gad HaCohen (Dudu Cohen) has a Ph.D. in Hebrew Bible from the Hebrew University. His dissertation is titled, Kadesh in the Pentateuchal Narratives, and deals with issues of biblical criticism and historical geography. Dudu has been a licensed Israeli guide since 1972. He conducts tours in Israel as well as Jordan.

Essays on Related Topics: