Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Part 2

Hatti’s Power Play with Egypt

Categories:

CDLI contributors. 2025. “Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin, Germany - Collections.” Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative (January 24, 2025).

One class of Amarna Letters includes the pharaoh’s correspondence with rulers of the large kingdoms of Hatti, Mittani, and even far away as the Kassite kingdom in Babylonia. These kings were peers of the pharaoh, or at least they considered themselves to be peers. They commonly used kinship language when they refer to the pharaoh, addressing him as their brother.

Correspondence with the Hittite Kings

There are only four Amarna Letters from Hatti, the kingdom of the Hittites, the dominant political power at the time in what is modern day Turkey and Syria. Two are quite broken (EA 43 and 44) so we can’t say much about them. The two better preserved letters (EA 41 and 42) are written from King Suppiluliuma I (ca. 1350–1322 B.C.E.) to the pharaoh. While the Hittite king employed scribes who used cuneiform to write in Hittite—these letters were written in Akkadian, the international language of diplomacy.

To appreciate the style and formulae used in the letters between the “great” kings in this period, here is the entire letter of EA 41 with brief explanations of its structure and contents. The letter heading is broken, and the letter is addressed to “Huriya” (a-na IḪu-u-ri-i-˹ia˺, perhaps, Akhenaten (or even Tutankhamun).

The letter opens with a royal greeting. King Suppiluliuma sends positive wishes for the pharaoh’s welfare, and even calls the pharaoh his brother:[1]

EA 41:1–6 [The message of the Sun,] Suppiluliuma, the gr[eat king, [the king of the land of Ḫ]atti; spea[k] to Ḫuriya, [the king of the land of E]gypt, my brother.

[It is we]ll [with me; may it be well with you; [with yo]ur [wives], your sons, your household, your troops, your chariots, [and w]ithin your land may it be very well.

Suppiluliuma then gives a short overview of the history between their royal houses, and their gift-giving, from the Hittites’ perspective:

EA 41:7–22 As for my envoys that I sent to your father and the request that your father requested between us: “Let us establish friendly relations!” then surely(?) I did not hold back. Whatever your father said, surely(?) I verily carried out and my request that I requested of your father, he did not withhold anything, he verily granted everything.

He then expresses his desire for the two kingdoms to resume diplomacy, citing past gift giving, and opens the door for a royal marriage between the two households:

Why have you withheld the shipments that your father sent when your father was alive? Now, my brother, you have ascended the throne of your father, and just as your father and I desired greeting gifts between us, so now may you and I thus enjoy good relations between us, and the request ‹that› I made to your father, to my brother [will I make:] “May we make a [mar]riage agreement between us.”

Next, Suppiluliuma lists what he would like to receive:

EA 41:23–43 [As for whatev]er the request to your father, [you, ]my [bro]ther, do not withhold. [...two s]tatues of gold: one [may it be standing], one may it be sitting; and two statues of women [of silve]r and much lapis lazuli and for [...] their large [s]tand, [may] my brother [send]. I ha]ve sent and [.....] and if my brother [desires....to give...] may my [broth]er give the[m].

[But if] my brother does [no]t desire to grant them; my chariots will finish [carr]ying linen sheets(?). I will return them to my brother. And whatever my brother desires, write to me that I may send to you.

Finally, Suppiluliuma includes an inventory of the gifts that he has sent pharaoh:

Now, for your greeting gift, one silver rhyton, [1 bi-ib-ru KÙ.BABBAR] a ram, five minas in weight, one silver rhyton, a breed ram, three minas in weight, two [ta]lents of silver, ten minas in weight, two large medicinal shrubs, have I sent to you.

The letter here focuses on gift-giving between the rulers. We know, however, more about the political relationship between these two kingdoms from other Amarna Letters written by northern Levantine elites to Egypt. These other letters suggest that Hatti was a regional power and a threat to Egyptian interests in the region.

Correspondence with Tušratta, the Hurrian King of Mittani

One clear example of the power play between Egypt and Hatti is connected to the fate of the Hurrian kingdom of Mittani, which lay to the southeast of Hatti. The letters between its royal family and that of Egypt show that the two dynasties had a long-standing relationship. In one letter, King Tušratta (ca. 1358–1335 B.C.E.), the last independent king of Mitanni, refers to the arranged marriage between a princess of Mitanni and the pharaoh, detailing the princess’ official presentation at court and the reading of the tablet that outlines her dowry:

EA 24:21:21-34 And now, when the wife of my brother comes, when she will be shown to my brother, may she be attired as my flesh(?) of my (flesh), and as my flesh may she be shown.[2] And may my brother assemble the entire land and all the other countries and the honored guests (and) all envoys should be present. And may they show his dowry to my brother, and may they spread out everything in the sight on my brother….

And may my brother take all the noble guests and all the envoys and all the other lands and the chariot warriors that my brother desires, and may my brother enter and may he spread out the dowry and may they be suitable (to his wishes).[3]

In another letter, Tušratta writes to the pharaoh complaining about the Hittite takeover of his territories, and describes his victory over his Hittites enemies:

EA 17:30-35 [Du]ring the life, moreover, of my brother, when it returned, when the land of Ḫatti in its entirety came as enemies against my land; Teshub, my lord, gave it into my hand and I slew it. Among them there was none that returned to their land.

We know from other evidence, however, that Tušratta was assassinated by members of his own court, and Suppiluliuma I turned Tušratta’s son, Šattiwaza into his vassal subject. The Hittite king further joined the two courts in marriage, cementing their political relationship by requiring Šattiwaza to marry one of his daughters. A cuneiform treaty made between the two rulers includes the following stipulations:

[T]he daughter of the King of Hatti shall be queen in the land of Mitanni. Concubines will be allowed for you…but no other woman shall be greater than my daughter. You shall allow no other woman to be her equal, and not one shall sit as an equal beside her. You shall not degrade my daughter to second rank. In the land of Mitanni she shall exercise queenship.[4]

Amurru Is Conspiring with Hatti

Another example of Hatti’s power plays comes from a letter from Rib-Hadda of Byblos to the pharaoh. He complains about Hatti, and even accuses a local kingdom, known as Amurru[5]—of conspiracy with the Hittite armies:[6]

EA 126:51–66 And as for the troops from (lit. of) Hatti, they have burned the lands in flames. I sent messages repeatedly; n[o] word returned to me. They seized all of the lands of the king, my lord, but my lord was silent about them. Here now, they are bringing troops from (lit. of) the lands of Hatti in order to seize the city of Byb[los], so show concern for [your] city! The king should not listen to the men of the army. They gave all of the king’s silver and gold to the sons of ʿAbdi-ʾAširte, and the sons of ʿAbdi-ʾAširte gave that (silver) to the strong king, and, consequently, they became strong.

Another letter from an elite of Amqi makes a similar complaint, which suggests that and attack from the Hittites was a real and imminent threat.

EA 363:7-23 Look, we ourselves are in the land of ʿAmqi. (As for) the cities of the king, my lord, Etakkama, the ruler of the city (and) the land of Qadesh, led troops of the land of Hatti and set the cities of the king, my lord, on fire. The king, my lord, should know so that the king, my lord, may give regular troops, and we may conquer the cities of the king, my lord, and dwell in the cities of the king, my lord, my god, my Sun god.

Letters from Aziru of Amurru suggest that he was playing both sides. Aziru affirms his obedience in his letters to the pharaoh. He even traveled to Egypt. However, it is clear from other evidence that Aziru eventually sided with Hittite interests, out of his own self-interest. Hatti was, after all, a more politically and militarily powerful actor in the region. (For more on him, see part 4.)

Addendum

The Dowry

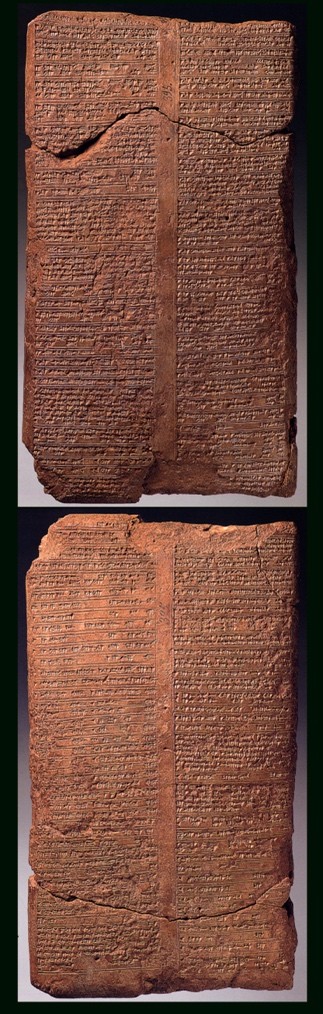

Another of Tušratta’s letters, written on large tablet organized in multiple columns, narrates a complex inventory of different types of wedding-gifts sent to Egypt along with the Mitanni royal princess:

EA 22 Tablet Image

CDLI contributors. 2025. “Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin, Germany - Collections.” Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative (January 24, 2025).

It lists horses, chariots and horse-riding equipment made of precious materials, which had a ceremonial function; weapons of precious metals; ornate jewelry, made of precious metals and stones (including lapis lazuli); shoes and garments of dyed and expensive cloth; vessels, basins, and furniture of precious metals, and containers with unguents and precious oils. Here is a small excerpt from the first column of the tablet:

EA 22:1.1–22 4 beautiful horses that run (swiftly). 1 chariot, its ṭulemu’s, its thongs, its covering, all of gold. It is 320 shekels of gold that have been used on it. 1 whip of pišaiš, overlaid with gold; its parattitinu, of genuine ḫulalu-stone; 1 seal of genuine ḫulalu-stone is strung on it. 5 shekels of gold have been used on it. 2 ša burḫi, overlaid with gold. 6 shekels of gold (and) 4 shekels of silver have been used on them. 2 (leather) uḫatati, overlaid with gold and silver; their center is made of lapis lazuli. 10 shekels of gold (and) 20 shekels of silver have been used on them. 2 maninnu-necklaces, for horses; genuine ḫulalu-stone mounted on gold; 88 (stones) per string. It is 44 shekels that have been used on them. 1 set of bridles for mules(?), of gilamu-ivory; their “thorns,” of go[ld;...]..., and...[...o]f alabaster; [...]..., their kuštappanni; [...]..., [...] of gilamu-ivory; and their [...], of gold with a reddish tinge. 2 leather nattullu, that are variegated like a wild dove.[7]

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

|

Last Updated

March 12, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Alice Mandell is Assistant Professor and William Foxwell Albright Chair in Biblical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies at Johns Hopkins University. She holds a Ph.D. in Hebrew Bible and Northwest Semitics from UCLA’s Department of Near Eastern Languages and Cultures. Her first book, Cuneiform Culture and the Ancestors of Hebrew is forthcoming from Routledge.

Essays on Related Topics: