Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Part 1

The Akkadian Letters in the Ancient Egyptian Capital, Akhetaten

Categories:

Map of the Near East in the Amarna Period; adapted by Aren Wilson-Wright from Wikimedia commons

The Amarna Letters and Diplomacy in the Mid-14th Century B.C.E.

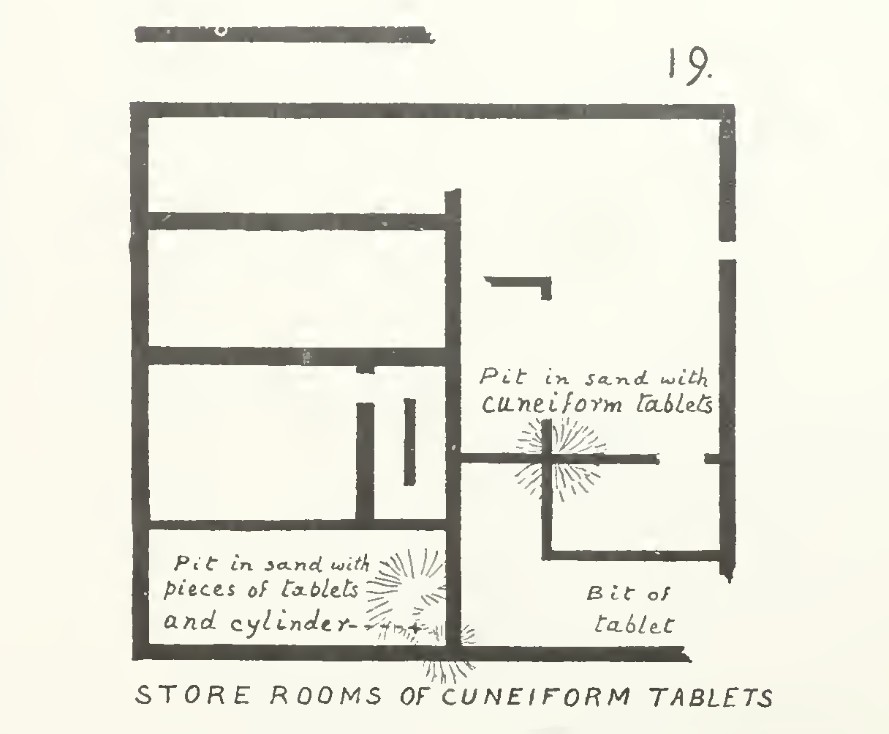

In 1887, clay tablets with Akkadian cuneiform (“wedge-shaped”) writing were discovered around the site of Tell el-‘Amarna, a site which sits on the east bank of the Nile, midway between the north and south of ancient Egypt, and that once served as ancient Egypt’s capital (see below). These early finds of cuneiform tablets—and others discovered in subsequent excavations of the site—totaled just over 380 tablets, plus some fragments.

Archaeologists traced the tablets back to a building that was the depot for the pharaoh’s letters from foreign dignitaries,[1] located across from the main palace complex and next to an Egyptian scribal center called in antiquity the “House of Life.” The textual and archaeological remains from this area suggest that it supported a bustling scribal community made up of scribes who were specialists in the Egyptian and cuneiform scripts.[2] The pharaoh employed scribes to create Egyptian text, but also who could read and write Akkadian, the language used for diplomacy in this period.

Most of the tablets were diplomatic letters dating roughly to the mid-14th century B.C.E., a time when Egypt controlled the Levant. There are also a few inventories of objects sent between royal houses, and 30 “scholarly” tablets,”[3] i.e., educational materials used to train scribes working for the pharaoh.

Ancient Akhetaten: A Short-Lived Capital

The Amarna Letters have made an important contribution to the study of ancient diplomacy, even though the letters discovered offer us only a small glimpse into Egyptian political history: the periods of Amenhotep III (ca. 1390–1353 B.C.E.), his son Akhenaten (ca 1353–1336 B.C.E.), and a few years beyond, during that of Akhenaten’s son Tutankhamen. The Amarna Period corresponds to the roughly the mid-14th century B.C.E.

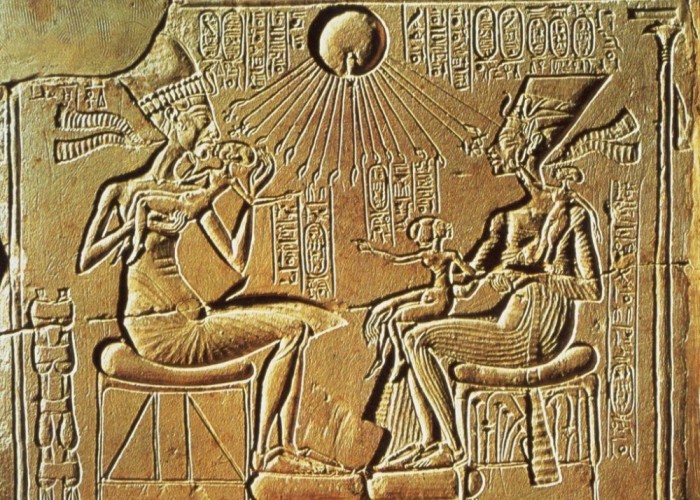

For a brief period, Tell el-‘Amarna, the name of the modern day site, was ancient Egypt’s capital city, called Akhetaten (“Aten’s Horizon”). The city was a new capital, founded by Pharaoh Amenhotep IV, who took the name Akhenaten (“Beneficial to Aten”) in honor of the deity Aten. Both the pharaoh’s name and that of his city reflect his aim of destabilizing the powerful cult of Amun—a chief god of the Egyptian pantheon—and other deities, to replace them with Aten and to position himself as the leader of this new religious movement.

During his two decades long reign, Akhenaten tried to transform Egypt. He established a new capital, and embellished it with unique architecture and art known today as the “Amarna” style. He also implemented religious and political reforms that destabilized the traditional cultic centers in Egypt, decreeing that the traditional gods of Egypt were subservient to the divine sun disc, Aten. Not only did Akhenaten portray Aten as the most important god, he presented himself and his family members as the intermediaries between Egypt and this god.

While Akhenaten accomplished much in his lifetime, his capital was abandoned shortly after his death. His son King Tutankhamun moved the center of power back to Thebes and reversed his father’s policies. The so-called Amarna reform was short-lived and had limited impact in Egypt. However, certain Canaanite Amarna Letters suggest that news of this Aten-based religious reform spread to the Levant. A letter from King Abimilki of Tyre includes several poems that compare the pharaoh to both the solar disk and also to the local storm god.

EA 147:5-15 “My lord is the sun god who has come forth over all lands day by day according to the manner of the sun god, his gracious father, who has given life by his sweet breath and returns with his north wind; of whom all the land is established in peace by the power of (his) arm; who has given his voice in the sky like Baʿal, and all the land was frightened at his cry.”

Biblical scholars have long noted the many parallels between Psalm 104 and the Great Hymn of the Aten.[4] Such parallels might suggest that certain Egyptian religious and literary texts influenced Hebrew writing scribes. While it is important to pay attention to scribal influences, it is also important to contextualize religious developments in their own unique contexts.

The Amarna-era reforms in Egypt in the mid-14th century B.C.E. were not a precursor to (much) later notions of biblical monotheism.[5] They predated the “biblical” period by several hundred years and took place in a totally different geographic, political, and religious context. Judean scribes and religious elites in 7th–5th century, who created biblical texts were not drawing upon their knowledge of Akhenaten’ short-lived reforms.

Akkadian in Egypt?

The large and unprecedented cache of cuneiform texts in Egypt raised important questions: Why were foreign scribes writing to the pharaoh in cuneiform? And why did the pharaoh employ cuneiform scribes? Given Egypt’s wealth and the pharaoh’s prestige, why didn’t the Egyptian court correspond with foreign allies and subjects using the Egyptian writing system? And/or why would this new Egyptian capital have an area designated for cuneiform scribes?

By the Late Bronze Age, cuneiform was used throughout the ancient Neat East, and adapted in different scribal settings, similar to how the Latin alphabet is used today for many different languages. Akkadian, a language that was spoken in ancient Mesopotamia (modern day Iraq), was the most widely used language written in cuneiform. It served as a “lingua-franca,” an international language for use between royal courts.[6] Specialist scribes working for Egypt wrote Akkadian letters and, in turn, read and interpreted letters from foreign rulers.

The Amarna Letters show that by the rule of Amenhotep III, the Egyptian court engaged scribes specializing in cuneiform to deal with outside rulers. Egypt thereby adapted to the contemporary protocols of international correspondence. (See addendum for the exception.) Egyptian Akkadian texts from the Hittite capital of Hattusa suggest that Egypt employed cuneiform scribes into the Ramesside period, which date to the 13th–late 12th centuries B.C.E. (ca. 1292–1191 B.C.E.).

Akkadian is classified by scholars as “east” Semitic. It underwent changes in grammar and phonology that differentiate it from Central Semitic languages, like Arabic, Aramaic, Hebrew, Phoenician, and Ugaritic. The Levantine languages are further grouped together into the Northwest Semitic subgroup; and, the languages of ancient Canaan (including Hebrew) are grouped in an even more narrow category, and are known as “Canaanite” dialects, due to similarities in their grammar and phonology.[7] In spite of grammatical, morphological, and phonological differences, Akkadian scribes in the Levant may have even recognized some cognate words, which were also used in their local Canaanite dialects.

The short list below pairs Akkadian words with their later Hebrew equivalents. Though, it is important to keep in mind that the Canaanite Letters reflects very different regions, speakers, and dialects of Canaanite (including the precursors to Phoenician and Transjordanian dialects), and that no evidence points to the existence of “Hebrew,” as we know it from the Hebrew Bible and 1st millennium inscriptions, in the Amarna Period.[8]

- Akkadian “to hear” is šemû, Hebrew root is שׁ.מ.ע.

- Akkadian “to go, walk” is alāku; Hebrew root is ה.ל.כ.

- Akkadian “house” is bītu; Hebrew is בַּיִת.

- Akkadian “heart” is libbu; Hebrew is לֵב.

Scribes in Western Asia did not speak Akkadian, even when performing administrative tasks. Rather, their education in this language was very limited: they learned Akkadian in order to be able to write in it. These scribes also learned some rudimentary Sumerian, a non-Semitic language, which was first written in Mesopotamia using the cuneiform script.[9]

While Akkadian was by far the most common language in the Amarna Letters exchanges, other languages written using cuneiform also appear: two letters written in Hittite (EA 31–32)[10] and one in Hurrian (EA 24). The letter senders had adapted cuneiform to their own administrative languages; they were able to write to Egypt in these languages because the pharaoh employed some scribes with a wide array of language abilities.

Cuneiform scribes working for Egypt were also trained in local Egyptian scribal practices. Sixteen Amarna Letters have traces of hieratic ink inscriptions. These small inscriptions are difficult to see today, yet they suggest that the scribes who received the pharaoh’s letters used their own script and the Egyptian language to notate and keep track of the pharaoh’s cuneiform letters. In spite of the differences in language, culture, religion, or geography, cuneiform scribes were able to bridge kings and elites throughout the ancient Middle East. The letters were even stored and used as a record of past alliances, disagreements, and royal political histories.

The Importance of the Letters

The information that we glean from the Amarna Letters about ancient diplomacy is limited to the mid-14th century B.C.E., with some reference to the correspondence and diplomatic alliances between even earlier kings in the 15th century B.C.E. Yet the letters offer insight into Egypt’s relationships with peer-level royal families and smaller polities, as well into changes in Egypt’s political and religious institutions in the Amarna Age.

Scholars debate when Akhenaten took control of the throne, but whenever it was, Akhenaten brought his father’s correspondence along with him—ostensibly as reference files—when he transferred rule to his new capital at Akhetaten, thus, we have some information about Amenhotep III as well.

A letter from Tušratta (EA 26), ruler of Mitanni—a Hurrian kingdom northeast of Egypt—to the Egyptian Queen Teye, Amenhotep III’s wife and Akhenaten’s mother, tells us about the transfer of power between these two kings. She worried that foreign rulers would not respect her son. They, in turn, were concerned that the new king would stop the flow of gifts to their lands. Cuneiform letters between royal courts assured both sides that diplomatic relations would continue, just as before.

Similarly, letters between Egypt and vassal rulers in the Levant reflect a regular flow of correspondence. For instance, Rib-Hadda, the ruler of Byblos—a coastal city located in modern day Lebanon—a prolific writer to Egypt, mentions older letters, stored in Egypt as proof of his service and loyalty:

EA 74:5–12 The king, the lord, should know that Byblos, a loyal maidservant of the king since the days of his forefathers, is intact. But, look now, the king has now abandoned his loyal city from his authority. The king should inspect tablets from (lit. of) his father’s house (to ascertain) whether the man who was present in Byblos was not a loyal servant.[11]

The letters therefore give scholars limited, yet, penetrating insight into the political and economic relationships forged between ancient royal families.

Addendum

Hittite Amarna Letters: Correspondence with the Luwian King of Arzawa

The Luwian kingdom of Arzawa sat in what is today western Turkey. In one letter, Tarḫundarasu, ruler of Arzawa, expresses skepticism that the pharaoh’s officials are dealing honestly with him and makes an unusual request that moving forward—all letters from Egypt would be written in Hittite rather than Akkadian. He apparently did not have his own Akkadian-language scribe:

EA 32:14–25 The scribe who reads out this tablet, let Ea the king of wisdom, and the Sun-god of the gate house protect him in good will! Let them hold the(ir) hands in good will around you! You, scribe, write to me in good will and add (your) name thereafter. The tablets that are brought (here) keep writing (them) in Nešite (i.e. Hittite).[12]

This request speaks to the influence of the Hittite kingdom and its scribal tradition, even at the Luwian (not Hittite!) kingdom of Arzawa. Notably, Tarḫundarasu was successful; the pharaoh writes back in Hittite (EA 31), written using the cuneiform script.[13] This letters suggests that Egypt employed cuneiform scribes trained in Hittite.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

|

Last Updated

March 12, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Alice Mandell is Assistant Professor and William Foxwell Albright Chair in Biblical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies at Johns Hopkins University. She holds a Ph.D. in Hebrew Bible and Northwest Semitics from UCLA’s Department of Near Eastern Languages and Cultures. Her first book, Cuneiform Culture and the Ancestors of Hebrew is forthcoming from Routledge.

Essays on Related Topics: