Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Queen Helena of Adiabene and Her Sons in Midrash and History

Mishna Nazir 1:5 – 4:1 from Cambridge MS Add.470.1 Folios 90v and 91 r combined.CC BY-NC 3.0

Part One

Helena’s Nazarite Vow

The Mishnah tells of Queen Helena of Adiabene, called Heleni HaMalka in Hebrew, who made a nazirite vow that she accidentally ended up doubling or tripling (m. Nazir 3:6):[1]

מַעֲשֶׂה בְהִילְנִי הַמַּלְכָּה, שֶׁהָלַךְ בְּנָהּ לַמִּלְחָמָה, וְאָמְרָה, אִם יָבֹא בְנִי מִן הַמִּלְחָמָה בְשָׁלוֹם אֱהֵא נְזִירָה שֶׁבַע שָׁנִים, וּבָא בְנָהּ מִן הַמִּלְחָמָה, וְהָיְתָה נְזִירָה שֶׁבַע שָׁנִים.

It is related the Queen Helena, when her son went to war, said, “If my son returns in peace from the war, I shall be a Nazirite for seven years.” Her son returned from the war, and she observed a naziriteship for seven years.

וּבְסוֹף שֶׁבַע שָׁנִים עָלְתָה לָאָרֶץ, וְהוֹרוּהָ בֵית הִלֵּל שֶׁתְּהֵא נְזִירָה עוֹד שֶׁבַע שָׁנִים אֲחֵרוֹת. וּבְסוֹף שֶׁבַע שָׁנִים נִטְמֵאת, וְנִמְצֵאת נְזִירָה עֶשְׂרִים וְאַחַת שָׁנָה. אָמַר רַבִּי יְהוּדָה, לֹא הָיְתָה נְזִירָה אֶלָּא אַרְבַּע עֶשְׂרֵה שָׁנָה:

At the end of the seven years, she went up to the land [of Israel] and Beth Hillel ruled that she must be a Nazirite for a further seven years. Towards the end of this seven years, she contracted ritual defilement, and so altogether she was a Nazirite for twenty-one years. R. Judah said: “She was only a Nazirite for fourteen years.”

The story presents Queen Helena as pious but ignorant. The vow was misguided for two reasons. According to the rabbis, a nazirite vow must be kept while in the land of Israel, which Helena does not know.[2] Second, nazirite vows are generally for a short duration; seven years is an unreasonable undertaking since if a nazarite vow is accidentally violated, it must be repeated from the beginning.

This is only one of a number of anecdotes the rabbis tell about Queen Helena and her sons, all of whom converted to Judaism. It captures the rabbis’ ambivalence about her, a righteous convert to Judaism who, at the same time, is a consummate outsider.

Her story, and that of her two sons, Izates II and Monobazus II, is told at length by Josephus, the late first century C.E. Jewish historian, in book 20 of his Antiquities of the Jews (17-96).[3] The rabbinic anecdotes about Helena and her sons are therefore, based on real people and likely inspired by real occurrences. Nevertheless, as well shall see, the rabbinic accounts are framed according to the rabbis’ loose grasp of Second Temple period history.[4]

Queen of Adiabene Goes to Jerusalem

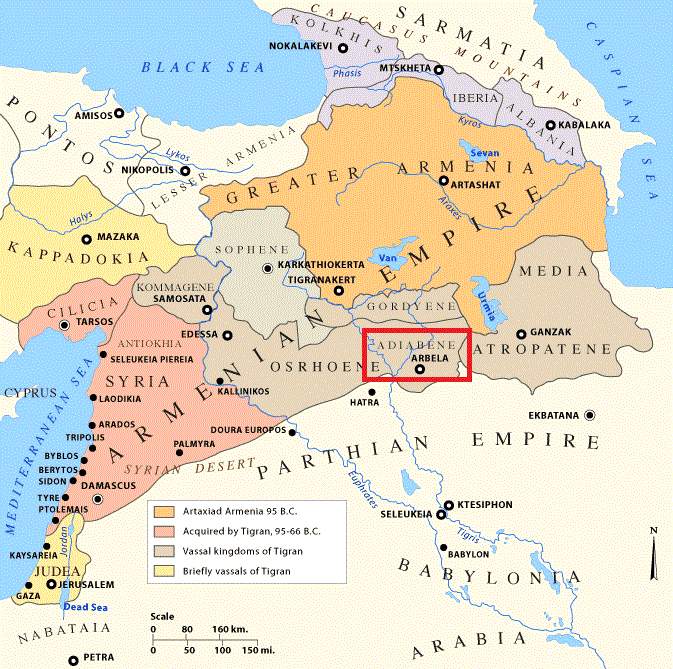

Helena was the queen of Adiabene, a region in what was once Assyria, along the northern end of the Tigris river, between the upper and lower Zab. After being a vassal of the Persian Empire and then the Parthian Empire, it became an independent state in the first century B.C.E., with its capital in the city of Arbela (modern Erbil; not to be confused with the Galilean city of the same name).

According to Josephus, at a certain point during the reign of her son, Izates II (34-58 C.E.), after both had converted to Judaism, Helena decided to move to Judea:

Helena, the mother of the king, saw that peace prevailed in the kingdom and that her son (=Izates II) was prosperous and the object of admiration in all men’s eyes, even those of foreigners, thanks to the prudence God gave him. Now she had conceived a desire to go to the city of Jerusalem and to worship at the temple of God, which was famous throughout the world, and to make thank-offerings there. (Ant. 20:49)

Helena’s Palace

Helena stayed in Jerusalem for many years, and famously built a palace there (Jud. War5:253), where she lived until her return to Adiabene toward the end of her life. The palace was eventually burnt at the end of the Great Rebellion (Jud. War 6:355). Nevertheless, the early Church Father Eusebius of Caesaria (ca. 260 – 340 C.E.), mentions that Helena’s monuments were still visible in his day:

But splendid monuments of this Helen, of whom the historian (=Josephus) has made mention, are still shown in the suburbs of the city which is now called Æelia (=Jerusalem), but she is said to have been queen of the Adiabeni.[5]

One of these “monuments,” i.e., Helena’s palace, may be the structure excavated by Doron Ben Ami and Yana Tchekhanovets in the Givati Parking Lot in 2007 right outside the City of David.[6] Another of these monuments is likely a reference to Helena’s enormous tomb.

Helena’s Tomb

Although we do not know when Helena moved to Jerusalem, according to Josephus she returned briefly to Adiabene in 58 C.E. when her son Izates II died at the age of 55[7] and her other son, Monobazus II, the older brother of Izates II, took the throne. She must have been at least in her seventies at the time of this trip. Although consoled by the fact that her other son was made king, “Helena was sorely distressed by the news of her son’s death, as was to be expected of a mother bereft of a son so very religious” (Ant. 20:93-94), and she died soon after her return.

Helena was not buried in her native land; apparently, she had already constructed a tomb for herself and Izates II in Jerusalem:

Monobazus [II] sent her bones and those of his brother [Izates II] to Jerusalem to be buried in the three pyramids that his mother had erected at a distance of three furlongs from the city of Jerusalem. (Ant. 20:94)

The tomb of Helena and Izates is a large structure that still exists. It was originally excavated by Louis Félicien de Saulcy in 1863, but misidentified it as “the Tomb of Kings,” namely of earlier Judahite kings. The number of sarcophagi found in this tomb (five complete and a piece of a sixth lid) demonstrate that it was used for more than just Helena and Izates II.

One sarcophagus has the remains of a woman referred to once as Queen Tzadan (צדן מלכתא) and another time as Queen Tzaddah (צדה מלכתה). Though some believe this to be Helena, others note that the body seems to be of a younger woman, not a septuagenarian.[8] If so, this Tzadda(n) was probably someone else from the royal family and unknown to us. (The sarcophagus is now in the Louvre.)

The Nazirite Vow: Confusing Berenice and Helena?

One element that does not appear in Josephus’ story is the nazirite vow. Nevertheless, Josephus does have a story about a “quasi-foreign” Jewish queen who made a nazirite vow, namely, Berenice, who was the daughter of King Agrippa I of Judea, son of Herod the Great.

Berenice, who was a generation younger than Helena, was already a fourth generation Jew on her father’s side. Her paternal great-grandfather, Antipater, was an Idumean convert, but she herself was born Jewish; moreover, she was of Hasmonean lineage from her grandmother Miriam (wife of Herod). At the same time, Berenice was also the Queen of Chalcis (a province in Syria), having married its king, Herod V (her paternal uncle), when she was a young woman.[9]

Josephus tells the following story about Berenice (Jud. War 2.15.1):

She was visiting Jerusalem to discharge a vow to God; for it is customary for those suffering from illness or other affliction to make a vow to abstain from wine and to shave their heads during the thirty days preceding that on which they must offer sacrifices.

The existence of two stories about two different Jewish queens making nazirite vows is surprising. It is possible that this was a practice among wealthy women who were in the public eye, and who had an interest in being seen as especially pious. Such behavior would have been even more attractive to “foreign” queens like Berenice and Helena who were quasi-outsiders. Moreover, nazirite vows would be uniquely accessible to women: the option of a woman making such a vow is explicitly mentioned in Numb 6:2.

Nevertheless, it is striking that Helena’s nazirite vow appears only in rabbinic literature while Berenice’s appears only in Josephus.[10] This suggests that the rabbis have confused Helena and Berenice.[11]

A number of similarities are evident in the lives of these two women that could lead to later generations confusing the them. Both:

- Were royalty;

- Were of foreign stock (at least partially);

- Ruled provinces far in the north (Adiabene and Chalcis);

- Lived in palaces in Jerusalem;

- Lived with their brothers.[12]

The identification of the Adiabene Jews with the Herodian Jews is explicit in at least one text from the Geniza, called Midrash Eser Galuyot, which states:

ומלך הורדוס ואגריפס בנו ומונבז בן בנו ק”ג שנה.

Herod was king, then Agrippa his son, then Munbaz his son – they ruled for 103 years total.[13]

Historically speaking, Munbaz (Monobazus II) was not related to Agrippa at all. This source has put the king of Adiabene into the lineage of the Judean royal family, and supports the possibility that the rabbis may have assumed that a story about Berenice was a story about Helena, because they were the same person.

This combining of two similar Second Temple historical characters into one is a pattern in rabbinic literature: the same seems to have happened with Agrippa I and his son Agrippa II,[14] with John Hyrcanus and his son Alexandar Jannai,[15] and, as we shall see in in the next part, with Helena’s two sons, Izates II and Monobazus II.

Part Two

The Generosity of Helena and Munbaz

The Mishnah (late 2nd century C.E.) describes the donations of Helena and her son Munbaz (=Monbazus II), mentioning his first (m. Yoma 3:10):

מֻנְבַּז הַמֶּלֶךְ הָיָה עוֹשֶׂה כָל יְדוֹת הַכֵּלִים שֶׁל יוֹם הַכִּפּוּרִים שֶׁל זָהָב. הִילְנִי אִמּוֹ עָשְׂתָה נִבְרֶשֶׁת שֶׁל זָהָב עַל פִּתְחוֹ שֶׁל הֵיכָל. וְאַף הִיא עָשְׂתָה טַבְלָא שֶׁל זָהָב שֶׁפָּרָשַׁת סוֹטָה כְתוּבָה עָלֶיהָ.

King Munbaz had the handles of all the vessels used on Yom Kippur made of gold. His mother Heleni made a golden candelabrum over the opening of the Temple sanctuary. She also made a golden tablet, on which the portion concerning the suspected adulteress was inscribed.[16]

The list of gold objects donated to the Temple communicates the wealth and piety of this family. Munbaz’s donations focus on preexisting Temple objects; since Temple utensils could not themselves be made of gold, he decided to beautify them by giving them golden handles. Helena’s donations, in contrast, are of new and unusual items.

Her first gift is a golden נברשת, a term that appears nowhere else in rabbinic literature and is generally translated as candelabrum or lamp. A candelabrum outside the sanctuary could be used for decoration, or for light in the night time. The Tosefta (Yoma 2:3) suggests that it was meant to shine at sunrise, perhaps as a picante decorative feature.[17]

Particularly intriguing is her donation of the sotah tablet, i.e., a tablet upon which a copy of the curse that the priest must write out for the woman accused of adultery who is to drink the bitter waters (see Num 5:23). First, it is striking that Helena is connected to both the nazirite and the sotah, two biblical institutions that appear back to back in the book of Numbers. Second, the sotah is a uniquely female ritual, but one that is quite negative, since it is designed to test suspected adulteresses.

Although the purpose of the golden sotah tablet was to make matters simpler for the priest, who could copy the required text onto parchment without bringing out a Torah scroll, having the text of the curse carved in gold seems discordant. It is possible that the rabbis are offering a slight jab to a woman who married her own brother, but more probably, it merely reflects their attempt to paint Helena as a pious, well-meaning woman yet naively lacking a sense of what is appropriate in the Jewish Temple.

Although Josephus says nothing about donating gold to the Temple, he does emphasize how fond she is of the Temple, and it is certainly possible that the royal family did donate money. This would fit with what we learn from Josephus elsewhere, that Helena and Izates donated money to save Judeans from famine.

Josephus: Funds During the Famine

The story is set in the time Helena decides to move to Jerusalem, an act which was enthusiastically supported by her son, Izates II, king of Adiabene, who even supplies her with funds that ultimately benefited the poor:

Her arrival was very advantageous to the people of Jerusalem, for at that time the city was hard pressed by famine and many were perishing from want of money to purchase what they needed. Queen Helena sent some of her attendants to Alexandria to buy grain for large sums and others to Cyprus to bring back a cargo of dried figs. Her attendants speedily returned with these provisions which she thereupon distributed among the needy. She has thus left a very great name that will be famous forever among our whole people for her benefaction. (Ant. 20:51-52)[18]

As Josephus himself lived through this famine (he would have been around 11), and directly benefited from Helena’s largesse, his appreciation here is likely real and personal.[19]

Josephus further claims that her son followed her lead:

When her son Izates [II] learned of the famine, he likewise sent a great sum of money to leaders of the Jerusalemites. The distribution of this fund to the needy delivered many from the extremely severe pressure of the famine. (Ant. 20:53)

Josephus’ account has a direct parallel in rabbinic literature. Ironically, the one member of the royal family that does not appear in Josephus’ version, Monobazus II, is the hero of the rabbinic account.

Tosefta: Munbaz Saves Judea from Famine

Tosefta Peah (4:18) describes how Munbaz expended his country’s treasury to save the Judeans from famine:

מעשה במונבז המלך שעמד וביזבז אוצרותיו בשני בצרות שלחו לו (אבותיו) אחיו אבותיך גנזו אוצרות והוסיפו על של אבותם ואתה עמדת ובזבזת את כל אוצרותיך שלך ושל אבותיך אמ’ להם אבותי גנזו אוצרו’ למטה ואני גנזתי למעלה שנ’ אמת מארץ תצמח…

It is related that King Munbaz got up and spent his entire treasury to assist [the Judeans] during years of famine. His kinsmen sent him a message: “Your fathers stored treasure and added to those of their ancestors, but you have got up and spent all of your treasury and that of your ancestors!” He said to them: “My fathers stored their treasure below, but I stored my treasure above, as it says (Ps 85:12), “truth springs up from the ground”…

The text continues in this vein, with Munbaz offering five more derashot about how his spending money on feeding the starving Jews is a better investment than stockpiling treasure.[20] Here again, Munbaz is painted in the light of truly pious man, and one whose loyalty is more with Judah than with his own nation. Moreover, Munbaz is the consummate rabbi, able to support his act with multiple midrashim on biblical verses.

Although the Rabbis bring up the same claim we find in Josephus, they not only conflate Izates II with Monobazus II, but forget entirely that the impetus for this amazing relief work was their mother, Helena.

Part Three

The Circumcision of Izates and Munbaz

Midrash Genesis Rabbah, which was compiled in the mid first millennium C.E., tells a story about Izates and Munbaz, whom it knows to be brothers, but who are described not as Adiabenites but as Egyptian Greeks from the Ptolemaic dynasty (46:10):

וּנְמַלְתֶּם אֵת בְּשַׂר עָרְלַתְכֶם – כְּנוֹמִי הִיא תְּלוּיָה בַּגּוּף, וּמַעֲשֶׂה בְּמֻנְבַּז הַמֶּלֶךְ וּבְזָוָטוּס בָּנָיו שֶׁל תַּלְמַי הַמֶּלֶךְ שֶׁהָיוּ יוֹשְׁבִין וְקוֹרִין בְּסֵפֶר בְּרֵאשִׁית, כֵּיוָן שֶׁהִגִּיעוּ לַפָּסוּק הַזֶּה וּנְמַלְתֶּם אֶת בְּשַׂר עָרְלַתְכֶם, הָפַךְ זֶה פָּנָיו לַכֹּתֶל וְהִתְחִיל בּוֹכֶה וְזֶה הָפַךְ פָּנָיו לַכֹּתֶל וְהִתְחִיל בּוֹכֶה, הָלְכוּ שְׁנֵיהֶם וְנִמּוֹלוּ,

“And circumcise the flesh of your foreskin” (Gen 17:1): [The foreskin] hangs on the body like a sore (nomi). It happened that king Munbaz and Zawatus (=Izates), the sons of King Ptolemy, were sitting and reading the book of Genesis. When they came to this verse, “and circumcise the flesh of your foreskin,” one turned his face to the wall and began to cry, and the other turned his face to the wall and [also] began to cry.[21] Then each of them went and had himself circumcised [without the other knowing].

לְאַחַר יָמִים הָיוּ יוֹשְׁבִין וְקוֹרִין בְּסֵפֶר בְּרֵאשִׁית כֵּיוָן שֶׁהִגִּיעוּ לַפָּסוּק הַזֶּה וּנְמַלְתֶּם אֶת בְּשַׂר עָרְלַתְכֶם, אָמַר אֶחָד לַחֲבֵרוֹ אִי לְךָ אָחִי, אֲמַר לֵיהּ אַתְּ אִי לְךָ, לִי לֹא אוֹי, גִּלּוּ אֶת הַדָּבָר זֶה לָזֶּה, כֵּיוָן שֶׁהִרְגִּישָׁה בָּהֶן אִמָּן הָלְכָה וְאָמְרָה לַאֲבִיהֶן בָּנֶיךָ עָלְתָה נוּמָא בִּבְשָׂרָן, וְגָזַר הָרוֹפֵא שֶׁיִּמּוֹלוּ, אָמַר לָהּ יִמּוֹלוּ.

Days later, they were sitting and reading the Book of Genesis; and when they came to the verse, “and circumcise the flesh of your foreskin,” one said to the other, “woe to you, brother,” and the other said, “woe to you, my brother, but not to me.” They then told one another [that they were circumcised.] When their mother found out, she went and told their father, “A sore has broken out on [our sons’] flesh and the doctor has ordered circumcision.” [The father] said, “they can be circumcised.”

Perhaps, being unfamiliar with the backstory of the Adiabene Jewish Kings other than that they were brothers and foreigners who converted to Judaism, the midrash picks the foreign king who commissioned the translation of the Torah into Greek as their father—the rabbis seem to know of only one Ptolemy—thereby explaining why the sons of a foreign king were reading the Torah.[22]

Putting aside the confusion about their origin, this midrash reflects a reception of the controversy about Izates II’s conversion and circumcision, which Josephus narrates at length, beginning with Izates II’s travels at a young age.[23]

The Youth of Prince Izates

Izates II was the second son of King Monobazus I (ca. 20s – ca, 33/34, C.E.) and his sister-wife Helena. Izates II was his father’s favorite and heir to the throne. To ensure no harm came to him from his many older half-brothers, Monobazus I sent his son to live in Characene, a province of Parthia south of Adiabene inhabited by an Arabic people called the Messenians, and which sat upon the lower Tigris and the Shatt al-Arab rivers.

As the son of the king of Adiabene, Izates lived as a guest of King Abinergaos (ca. 10-23 C.E.), in Charecene’s capital, Charax-Spasini[24] (perhaps modern day Tell Naysan), an important port city on the Shatt al-Arab River, near the Persian Gulf. He was soon married to the king’s daughter, a woman named Symachos.

Izates Meets Ananias

It was through the women of King Abinergaos’ family that Izates II first came in contact with Judaism:

Now during the time when Izates resided at Charax Spasini, a certain Jewish merchant named Ananias (Hebrew חנניה) visited the king’s wives and taught them to worship God after the manner of the Jewish tradition. It was through their agency that he was brought to the notice of Izates [II], whom he similarly won over with the co-operation of the women. (Ant. 20:34)

At this point, Izates II had not yet formally converted, but was certainly in the Jewish orbit. But just as Izates II had turned to the Jewish faith after meeting Ananias, so had his mother, who, as Josephus writes, “had likewise been instructed by another Jew and had been brought over to their laws….” Thus, when Izates II arrived back in Adiabene in ca. 34 C.E. to assume the throne,[25] and he “learned that his mother was very much pleased with the Jewish religion, he was zealous to convert to it himself.”

According to this, Helena had formally converted whereas Izates II had not. The reason for this was likely because Izates II, being a man, would need to be circumcised.[26] But this, in Izates II’s view, was not really an obstacle, “since he considered that he would not be genuinely a Jew unless he was circumcised, he was ready to act accordingly” (Ant. 20:38).

Helena Objects

Despite having converted to Judaism, and despite her support of Izates II’s commitment to Jewish faith, Helena did not want her son to go through with the circumcision:

When his mother learned of his intention, however, she tried to stop him by telling him that it was a dangerous move. For, she said, he was a king; and if his subjects should discover that he was devoted to rites that were strange and foreign to themselves, it would produce much disaffection and they would not tolerate the rule of a Jew over them. Besides this advice she tried by every other means to hold him back. He, in turn, reported her arguments to Ananias. (Ant. 20:39-40)

Apparently, Izates II was either hiding his interest in Judaism, or, more likely, worship of the Jewish god would not per se be considered a betrayal by his polytheistic subjects, since they worship multiple gods. Circumcision, however, would mean that Izates II was following the Jewish religion exclusively and abandoning the local gods, which would be considered insulting by his subjects. Helena’s attitude therefore seems more practical and less zealous than that of Izates, who turned to his Jewish mentor for support.

Ananias Objects

Surprisingly Ananias, the man who brought Izates to Judaism and who had returned with him to Adiabene, supported Helena:

The latter expressed agreement with the king’s mother and actually threatened that if he should be unable to persuade Izates, he would abandon him and leave the land. For he said that he was afraid that if the matter became universally known, he (Ananias) would be punished, in all likelihood, as personally responsible because he had instructed the king in unseemly practices. The king could, he said, worship God even without being circumcised if indeed he had fully decided to be a devoted adherent of Judaism, for it was this that counted more than circumcision. He told him, furthermore, that God Himself would pardon him if, constrained thus by necessity and by fear of his subjects, he failed to perform this rite. (Ant. 20:40-42)

Louis Feldman (Loeb Classics, ad loc.) suggests that Ananias is not making a legal argument that circumcision is unnecessary, but that Izates can exempt himself from it because doing it would endanger his life, invoking what later became the rabbinic principle of וחי בהם (“live by them”), according to which it is permitted to violate almost any law to save one’s life.

That circumcision was a “given” in this period for becoming Jewish, if not a formal requirement, is implied in Josephus’ description of how two of King Agrippa I’s daughters married gentile kings: Drusilla married Azizus, King of Emesa (Ant. 20:139), and Berenice married Polemon II, King of Pontus (Ant. 20:145), but both kings agreed to be circumcised to please their Jewish wives.[27]

Eleazar Convinces Izates II to Circumcise

Izates II only temporarily capitulated to Ananias and his mother. Things changed when he came in contact with yet another Jew, a visitor from the Galilee named Eleazar,

…who had a reputation for being extremely strict when it came to the ancestral laws, urged him to carry out the rite. For when he (Eleazar) came to him (King Izates II) to pay him his respects and found him reading the law of Moses, he said: “In your ignorance, O king, you are guilty of the greatest offence against the law and thereby against God. For you ought not merely to read the law but also and even more to do what is commanded in it. How long will you continue to be uncircumcised?”

Eleazer’s speech is very similar in character to what Izates and Munbaz say to each other in Genesis Rabbah. Both imagine the protagonist experiencing a feeling of hypocrisy while studying the Torah but remaining uncircumcised. Moreover, just as Izates and Munbaz immediately circumcise themselves at this point in the Genesis Rabbah account, Izates II does the same immediately after Eleazar’s speech, according to Josephus’ Antiquities, informing his mother and Ananias of the fait accompli.

Monobazus II’s Conversion

Later on in the story, Josephus describes how Izates II’s older brother, Monobazus II, jumped on the Judaism bandwagon:

Izates’ brother Monobazus and his kinsmen, seeing that the king because of his pious worship of God, had won the admiration of all men, became eager to abandon their ancestral religion and to adopt the practices of the Jews. (Ant. 20:75)[28]

Josephus does not say whether Monobazus II was circumcised, but the implication is that he was and that he converted fully. In this sense, the midrashic tradition that Izates and Munbaz had themselves circumcised is broadly accurate. So is the focus on the mother’s concern about the fallout from her sons’ circumcision, which is reminiscent of Helena’s attempt to convince Izates II not to go through with it. But whereas the midrash deals only with the possible fallout with their father, Izates II had to deal with the political fallout among his noblemen.

Attempts to Depose Izates II for Being Jewish

After describing Izates II’s conversion, Josephus goes on to state that, “although Izates himself and his children were often threatened with destruction, God preserved them.” To put it in less apologetic terms, the fears expressed by Helena and Ananius turned out to be well-founded, since Josephus goes on to record two separate attempts to depose Izates II.

1. Plotting with the King of the Arabs

First, the noblemen contacted Abias, king of the Arabs, promising if he attacked Adiabene, they would betray Izates.[29] Abias attacked and, true to their word, they snuck out of the battle. Nevertheless, Izates and his army won the battle and he killed the noblemen. Josephus claims that Abias killed himself when he saw he would be captured (Ant. 20:76-80).

2. Plotting with the King of the Parthian Empire

Despite Izates II’s success, Josephus writes, the remaining noblemen were not deterred:

Foiled in their first attempt, when God delivered them over to the king, the nobles of Adiabene did not even then keep quiet but wrote another letter, this time to Vologases, king of the Parthians, urging him to put Izates to death and to appoint for them another overlord of Parthian descent; for, they said, they had come to loathe their own king who had overthrown their traditions and had become enamored of foreign practices. (Ant. 20:81)

Vologases arrived with his army[30] and sent a reminder to Izates that he (Vologases) was the ruler of an empire, not just a small nation, “and that even the God whom he worshipped would be unable to deliver him from the king’s hands.” The Jewish king of Adiabene then responds in classic biblical and Maccabean style:

Izates replied that he was aware that the Parthian empire was far larger than his own, but for all that, he was even more certain that God is mightier than all mankind. (Ant. 20:89)[31]

Whether this back and forth has any historical basis or was merely Josephus’ pious rhetoric placed in Izates II’ mouth, Josephus continues by describing his further pious behavior, including fasting, putting on ashes, and praying to God.[32] Unluckily for Vologases, his siege of Adiabene encouraged neighboring Scythians to invade Parthia itself, and he was forced to drop his siege and protect his own territory. “Thus by the providence of God, Izates escaped the threats of the Parthians.”

We see from this the danger Izates II placed himself in with his decision to circumcise and fully identify with the Jews. In Josephus’ understanding, the fact that Izates II was not conquered shows that God was on his side.

Rabbinic Memories of Izates’ Success and Helena’s Concern

The story about the attempts to depose Izates II and his “miraculous” success in withstanding these attempts may be reflected in the end of the midrash on Ptolemy’s sons quoted above:

מַה פָּרַע לוֹ הַקָּדוֹשׁ בָּרוּךְ הוּא אָמַר רַבִּי פִּינְחָס בְּשָׁעָה שֶׁיָּצָא לַמִּלְחָמָה עָשׂוּ לוֹ סִיעָה שֶׁל פֶּסְטוֹן וְיָרַד מַלְאָךְ וְהִצִּילוֹ.

How did the Holy One, blessed be He, repay [Ptolemy]? Said R. Phinehas: “When [Ptolemy] went out to war, a band of enemies attacked him, and an angel descended and rescued him.

Similarly, it seems possible that the story about Izates’ narrow escapes from the Arabs and the Parthians are what inspired the (above-quoted) Mishnah’s reference to Helena’s thankfulness for her son’s military successes in the story of the nazirite vow (m. Nazir 3:6).[33]

Although the rabbis do not seem to know Josephus’ account about the attempts to overthrow Izates II because of his conversion, and certainly have no independent knowledge of Adiabenite history, certain midrashim may reflect the rabbis’ late reception of this snippet of information, which gets incorporated in different ways in the Mishnah and midrash.

Part 4

Helena’s Giant Sukkah and Her Descendants in Judea

The Tosefta (Sukkah 1:1) describes a debate between R. Judah and his colleagues about Helena’s oversized sukkah:

סוכה שהיא גבוהה למעלה מעשרים אמה פסולה ור’ יהודה מכשיר אמ’ ר’ יהודה מעשה בסוכת הילני שהיתה גבוהה מעשרים אמה והיו זקנים נכנסין ויוצאין אצלה ולא אמר אחד מהן דבר אמרו לו מפני שהיא אשה ואשה אין חייבת בסוכה אמ’ להם והלא שבעה בנים תלמידי חכמים היו לה וכולן שרויין בתוכה

A sukkah whose roof is higher than twenty cubits is invalid. R. Judah accepts it as valid. R. Judah said: “It is related that the roof of Helena’s sukkah was higher than twenty cubits, and the elders would come in and out of it to visit her and no one said a thing against it.” They said to him: “That was because she was a woman, and women are exempt from the commandment to dwell in a sukkah.” He said to them: “But did she not have seven sons, all of whom were Torah scholars, and all of them dwelt in it as well!”[34]

Two things stand out in this text. First, yet again we see Helena painted as a pious woman who is ignorant of Jewish practice and therefore, with the best of intentions, builds an invalid sukkah. Helena, who builds giant palaces and gives lavish if unusual donations of golden implements to the Temple, would naturally build a giant sukkah, not knowing that according to rabbinic law there is a height limit.

Second, R. Judah, who wishes to use Helena’s sukkah as a support for his view, argues that the sukkah must be valid because Helena’s sons were Torah scholars, and they would have adjusted the sukkah to the proper height if there was really a problem.

Helena’s (Grand)sons Live in Jerusalem

R. Judah’s comment about Helena’s seven sons living with her in Jerusalem again reflects how the rabbis seem to know something about the Adiabene royal family, but that the snippet they knew was out of context and reinterpreted.

Josephus relates how Vardanes I (ca. 40-45 C.E.), King of Parthia was a military adventurer, and tried to convince Izates II, his father’s ally,[35] to attack Rome with him (Ant. 20:69), but Izates refused:

For Izates, knowing well the might and fortune of the Romans, thought that Vardanes was attempting the impossible. Moreover, he was the more reluctant because he had sent five sons of tender age to get a thorough knowledge of our native language and culture, besides his mother who had gone to worship in the temple, as I have said already. (Ant. 20:70)

Izates II sent his five sons to Jerusalem, where they could live as Jews, and his mother lived there as well. An attack on Rome would put his family in danger of retaliation by the Romans, since Judea was a Roman province, and so, Izates II had no choice but to refuse.[36]

Although the Rabbis talk about Helena’s sons, when they are really Izates II’s, and they speak about seven when there were five (Josephus may well have known them personally), the rabbis do seem to be working off a snippet of tradition or information that they had.

Torah Scholars or Warriors?

The other major change between Josephus’ account and the rabbis about these sons is that whereas the rabbis describe them as Torah scholars, Josephus describes the military prowess of the Adiabenite royalty who lived in Judea, and how they took part in the Great Rebellion against Rome (66-70 C.E.):

Now they considered their most excellent [fighters] to be the relatives of Monobazus, the king of Adiabene—Monobazus and Cenedeus. (Jud. War. 2:520)

These relatives are very likely two of the five sons of King Izates II that he sent to study in Judea,[37] or perhaps the sons of these sons.[38] At the end of the war, after the city had been burned, the surviving members of the royal family surrendered to Titus and were taken back to Rome as hostages.[39] Although Monobazus II never went to war with Rome, it is clear that Adiabene was on the side of the Jews and many of the royal family fought as Jews.[40]

We thus see how Izates II’s five sons, who likely fought with the Judeans in the Great Rebellion, were morphed into Helena’s seven Torah scholar sons who know how to make a proper sukkah. Either way, unlike their (grand)mother Helena, these sons are insiders, who are integrally part of the Jewish people, something the rabbis seem to unwilling or unable to grant her.

Foreign Insiders – the Royal Family of Adiabene

We know nothing about what happened to Adiabene’s Jews after the Great Rebellion. Its king, Monobazus II was himself Jewish, but we do not know about his children.[41] Adiabene remained independent until 115 C.E., when it was conquered by the Roman Emperor, Trajan. The final ruler of the kingdom was named Meharaspes; we do not know if he was Jewish or what his relationship to Monobazus II was.

But all these are historical questions; the rabbis knew little about Judea’s history and virtually nothing about Adiabene. Instead, they tried to incorporate the snippets of information they knew about Queen Helena and her son(s) into their picture of the end of the Second Temple period. Because they grappled with Helena and Munbaz’s insider/outsider status, they often confused aspects of their story with what they knew about the Judean royal family, the Herodians, also insiders/outsiders of sorts.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

May 24, 2018

|

Last Updated

March 20, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Malka Zeiger Simkovich is a the Crown-Ryan Chair of Jewish Studies at Catholic Theological Union in Chicago, and the director of their Catholic-Jewish Studies program. She holds a Ph.D. in Second Temple Judaism from Brandeis University, an M.A. in Hebrew Bible from Harvard University, and a B.A. in Bible Studies and Music Theory from Yeshiva University’s Stern College. In addition to her many articles, Malka is the author of The Making of Jewish Universalism: From Exile to Alexandria (2016) and Discovering Second Temple Literature: The Scriptures and Stories that Shaped Early Judaism (2018).

Essays on Related Topics: