Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Symposium

What We Know about the Egyptian Places Mentioned in Exodus

Figure 1: Map of the approximate locations of the toponyms from the exodus (Illustration by author)

We have much more textual evidence available for Egyptian toponyms compared to cities and towns located in Canaan. This evidence includes written documents and inscriptions from the sites themselves.

Piramesses and Avaris

The first Egyptian toponyms in the exodus story are the “supply cities” (or “supply depots”)[1] that Pharaoh forces the Israelites to build in Pithom and Ramesses:

שמות א:יא ...וַיִּבֶן עָרֵי מִסְכְּנוֹת לְפַרְעֹה אֶת פִּתֹם וְאֶת רַעַמְסֵס.

Exod 1:11 … They built supply cities for Pharaoh, Pithom and Ramesses.[2]

Only one city in antiquity had the name Ramesses: Piramesses, which was identified by the Egyptian Egyptologist Labib Habachi (1906-1994) at the archaeological site of Qantir and was conclusively proven to be Piramesses by the wealth of inscriptional material found there.[3]

“Pi/Pr” – Linguistic Conversions between Languages

The Bible calls this site Ramesses rather than Piramesses; this is not unusual, given the minor differences that occurred when Egyptian was reflected in Hebrew. In particular, Hebrew sometimes dropped the pi/pr, “house/estate of” opening that was very common in Egyptian toponymy, e.g., Pi-Amun, Pi-Wadjet, Pi-Thoth, Pi-King-of-Upper-and-Lower-Egypt-Neferirkare, etc.[4] It should be noted that even in Egyptian the pi/pr was also omitted on occasion.[5]

The Founding of Piramesses

Piramesses was originally founded by the 19th dynasty Pharaoh Seti I (ca. 1304-1289 BCE) as a royal residence, though it was named Piramesses when it was expanded by Pharaoh Ramesses II (ca. 1289-1223 BCE), Seti I’s son.[6] (If it had a name during the reign of Seti I, we don’t know what it was.)As demonstrated by the ground-penetrating radar (GPR) and Caesium-Magnetometry surveys (performed in 1996, 2003, and 2008), Seti I built the residence on virgin ground, where no city had been built before.[7] He likely chose the spot for two reasons:

A Northern Dynasty – In contrast to the Pharaohs of the 18th dynasty who were natives of the southern capital, Thebes, the 19th dynasty Ramessides hailed from the north.[8] Seti I wished to vest power where the Ramessides had their tribal power base and to avoid the southern capital, Thebes, where he would have been less welcome.

Proximity to the Levantine Population – Qantir, the site of Piramesses, is located 2 km (1.25 mi) east of Avaris/Tell el-Dabˁa in the eastern Delta region.[9] Although founded during the Middle Kingdom by the kings of the native Egyptian 11th dynasty, Avaris later served as the capital city for the foreign Semitic-Asiatic Hyksos (15th dynasty), during what is known as the Second Intermediate Period (ca. 1646-1538 BCE).[10]

Even after the fall of the Hyksos dynasty, Avaris had one of the largest populations of Semitic-Asiatics in Egypt. Thus, Piramesses may have been constructed to keep an eye on the large Semitic-Asiaitic population in the vicinity. Avaris was abandoned sometime during the 19th dynasty.[11] While no one knows exactly when or why the area was abandoned by its Semitic population or where they went, the overall timing coincides with the movement of the river away from Avaris.

Israelites in Goshen

The fact that the delta region was filled with Levantine Asiatics until the mid-19th dynasty fits well with the biblical account of conditions in Egypt up to the exodus since the area around Avaris and Piramesses, what the Bible refers to as Goshen (or “the land of Ramesses,” Gen 47:11), is where the Israelites are said to have dwelt (e.g., Gen 47:6, 27; Exod 8:18, 9:26). But as the term Goshen only appears in the Bible, we do not know if the term has an Egyptian origin or if it is only an Israelite term.[12]

On the Border with Sinai

In addition to the construction of Piramesses near the Eastern frontier, the Ramessides built up considerable defenses along the Eastern frontier to mitigate against possible incursion. Under Ramesses II, the expanded city became the capital of Egypt. It was abandoned in favor of Tanis by the 21st dynasty (mid-11th cent.) when the Pelusiac branch of the Nile moved away from the city in the process of silt deposition and erosion.

Pithom (Etham) and Sukkot

Pithom, also called Etham,[13] was located in the Wadi Tumilat[14] to the east of the Nile Delta, and is identified by scholars with Tell el-Retabah. In ancient times, the road between Piramesses and Pithom would have been about 65 km (40 mi) or approximately 2 days of travel by foot. The wadi provided way stations for semi-nomadic tribes from the Levant and, like the delta in general, had a significant Semitic-Asiatic population during the Second Intermediate Period. Nevertheless, Tell el-Retabah was only sporadically occupied at the beginning of Dynasty 18, as shown by recent excavations there.[15] The site was built up in the 19th dynasty and fell into disuse during the Saite period (670-525 BCE).[16]

Ramesses II built new fortifications and a Temple of Atum at Tell el-Retabah, and the site gained the epithet pr-tm ṯkw.[17] The meaning of the first term in this new epithet, Pithom/pr-tm is “house of Atum,”[18] named after a creator god. The second word, Tjeku/ṯkw was first proposed to be identified as Sukkot by Henri Brugsch,[19] an identification that was quickly accepted by many scholars.

Sukkot

Despite similarities between the pronunciation of Sukkot and Tjeku, this identification is problematic because of the geography of the Wadi Tumilat.[20] The itinerary texts in the Torah describe Etham (=Pithom) as a way station following Sukkot when the Israelites are leaving Egypt (Exod 13:20; Num 33:6-7):

שמות יג:כ וַיִּסְעוּ מִסֻּכֹּת וַיַּחֲנוּ בְאֵתָם בִּקְצֵה הַמִּדְבָּר.

Exod 13:20 They set out from Sukkot, and camped at Etham, on the edge of the wilderness.

To complicate matters further, some scholars point to the similarity in sound (s-k-t) between the modern Arabic name Tell el-Maskhuta and the biblical name Sukkot.[21] But Tell el-Maskhuta is east of Tell el-Retabah (Pithom),[22] whereas the biblical author is clearly picturing Sukkot as west of Pithom. This would likely place the Israelite encampment of Sukkot near the entrance to the wadi, possibly near the modern town of Abou Hammad. Sukkot should therefore not be understood as the name of a city at all, but, like Goshen, a regional designation, describing the area located between Piramesses and Pithom (Exod 13:20; Num 33:6).[23] This suggestion is consistent with the use of Tjeku in Papyrus Anastasis VI (54-56):

We have finished letting the Shasu tribes of Edom pass the Fortress of the House of Merneptah, l.p.h.,[24] which is in Tjeku, to the pools of Pithom of Merneptah, which are in the Tjeku, in order to sustain them and sustain their flocks by the pleasure of Pharaoh, l.p.h.[25]

According to this papyrus, the Shasu traveled from the Fortress of Merneptah to Pithom, both of which were in Tjeku.

On the Way Out of Egypt

The second cluster of Egyptian toponyms is found in Exodus 14 in the description of the Israelites leaving Egypt. Having arrived at Etham (=Pithom) at the edge of the wilderness, God gives Moses the following command:

שמות יד:ב דַּבֵּר אֶל בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל וְיָשֻׁבוּ וְיַחֲנוּ לִפְנֵי פִּי הַחִירֹת בֵּין מִגְדֹּל וּבֵין הַיָּם לִפְנֵי בַּעַל צְפֹן נִכְחוֹ תַחֲנוּ עַל הַיָּם. יד:ג וְאָמַר פַּרְעֹה לִבְנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל נְבֻכִים הֵם בָּאָרֶץ סָגַר עֲלֵיהֶם הַמִּדְבָּר.

Exod 14:2 Tell the Israelites to turn back and camp in front of Pi-hahiroth, between Migdol and the sea, in front of Baal-zephon; you shall camp opposite it, by the sea. 14:3 Pharaoh will say of the Israelites, "They are wandering aimlessly in the land; the wilderness has closed in on them."

The fact that the Israelites are in front of both Pi-Hahiroth and Baal-Zephon and between Migdol and the sea is meant to convey the idea of being surrounded on all sides. The Israelites follow this command and Pharaoh, believing that the Israelites are lost—“the wilderness has closed in on them”—chases them down and meets them there:

שמות יד:ט וַיִּרְדְּפוּ מִצְרַיִם אַחֲרֵיהֶם וַיַּשִּׂיגוּ אוֹתָם חֹנִים עַל הַיָּם כָּל סוּס רֶכֶב פַּרְעֹה וּפָרָשָׁיו וְחֵילוֹ עַל פִּי הַחִירֹת לִפְנֵי בַּעַל צְפֹן.

Exod 14:9 The Egyptians pursued them, all Pharaoh's horses and chariots, his chariot drivers and his army; they overtook them camped by the sea, by Pi-hahiroth, in front of Baal-zephon.

This encounter ends with the account of the splitting of the sea and the Israelites’ ultimate escape.

Pi-Hahiroth

Pi-Hahiroth[26] reflects the Egyptian pr-ḥwt-ḥrt.[27] The toponym follows Egyptian convention beginning with the hieroglyphic pr-ḥwt, “estate of the temple”[28] or “house of the precinct.” It ends with the goddess determinative[29] indicating that the final element, ḥrt, is theophoric. The name should mean “Estate of the Temple of (the goddess) Heret,” but no such goddess is known.

Early Egyptologists suggested that it might mean “House of (the goddess) Hathor,” assuming that the word ḥrt was an unusual or mistaken spelling of Hathor. William F. Albright suggested that it might mean “the mouth of the canals,” perhaps based on the Akkadian word ḥirītu, meaning “ditch or canal" (CAD 6:201), yet this creative solution ultimately does not solve the problem of the theophoric name.[30]

I would argue that ḥrt may be an abbreviated spelling of ḥry(t)-tp, “the one who is on top.”[31] The term ḥry(t)-tp is one of the epithets of the Uraeus serpent goddess, Wadjet,[32] and therefore, the name would mean, “Estate of the Goddess, who is on top (=Wadjet).”

Location

The toponym pr-ḥwt-ḥrt appears in one extra-biblical text, Papyrus Anastasis III (3:3):

The (Sea of) Reeds (pȜ-ṯwfy) comes to papyrus reeds and the (Waters-of)-Horus (pȜ-ḥr) to rushes. Twigs of the orchards and wreaths of the vine-yards [ … ] birds from the Cataract region. It leans upon [ … ] the Sea (pȜ ym) with bg-fish and bȗrἰ-fish, and even their hinterlands provide it. The Great-of-Victories youths are in festive attire every day; sweet moringa-oil is upon their heads having hair freshly braided. They stand beside their doors. Their hands bowed down with foliage and greenery of Pi-Hahirot (pr-ḥwt-ḥrt) and flax of the Waters-of-Horus. The day that one enters (Pi)ramesses (wsr-mȜˁ-rˁ stp-n-rˁ) l.p.h., Montu-of-the-Two-Lands. (P. Anastasis III 2:11-3:4)

This document, dated to the third year of Ramesses II’s successor, Merneptah (ca. 1223-1213 BCE), locates Pi-Hahiroth on the way from the Sea of Reeds (pȜ ṯwfy) towards Piramesses.

Baal-Zephon

The biblical text parallels “before Pi-Hahiroth” and “before Baal-Zephon,” implying that the two sites are adjacent; this is not surprising as many small outposts were scattered across the Sinai.Baal-Zephon is attested in Papyrus Sallier IV (vs. 1:6),

To Amūn of the temple of the gods; to the Ennead that is in Pi-Ptaḥ; to Baˁalim, to Ḳadesh, and to Anyt; (to) Baˁal Zephon (bˁr-ḏȜpn), to Sopd.[33]

Unlike the previous Egyptian toponyms, Baal-Zephon has a Semitic etymology. Baal is common to many Semitic languages and means “lord”;[34] it is often used as an epithet for a god. The name was used during the Old Babylonian period for a variety of deities including Marduk (Bel) but is best known from the Bible as an epithet for the northwest Semitic storm-god (Hadad/Adad).

The Hyksos who worshipped the storm god associated this epithet with the Egyptian storm god, Seth, an association the Egyptians continued to use after the Hyksos left Egypt. Given that the toponym Baˁal Zephon in Papyrus Sallier IV is written with the Seth determinative,[35] Baal in this toponym may be a reference to Seth.

The second element of the toponym, the word zephon, means “north” in Semitic languages. However, Zephon by itself also appears as a toponym in Amarna Letter 274, most likely as a name of a Levantine city. Thus, it is unclear whether zephon in Baal-Zephon refers to a direction, yielding “Baal of the North,” or a place, “Baal of (the city) Zephon.”

Two Oases Serving as Lookout Posts?

Pi-Hahiroth and Baal-Zephon were likely near to each other and near the water. The two sites were probably small oases or marshes located near high ground that acted as lookout posts to provide surveillance over the eastern frontier for the fortresses on the Way of Horus, a road that ran from Tjaru on the Western edge of the Sinai to the Philistine Pentapolis in Canaan. This places their locations northeast of the Wadi Tumilat.

According to Exodus 14:2-3, the Israelites turn back at God’s command. If this was intended to provoke Pharaoh into chasing them, the choice to have the Israelites encamp specifically before Egyptian lookout posts certainly heightens the provocative effect.

Migdol

The idea that Pi-Hahiroth and Baal-Zephon were lookout posts fits with a third toponym in this same section, Migdol, one of the fortresses on the Way of Horus, a road that was guarded by several fortresses intended to control the flow of traffic from the Levant. The Egyptian version of this name, mˁktir actually derives from a Semitic loan word מגדל, “tower.”[36] The location of Migdol is unknown, but the name appears in a couple of extra-biblical sources.

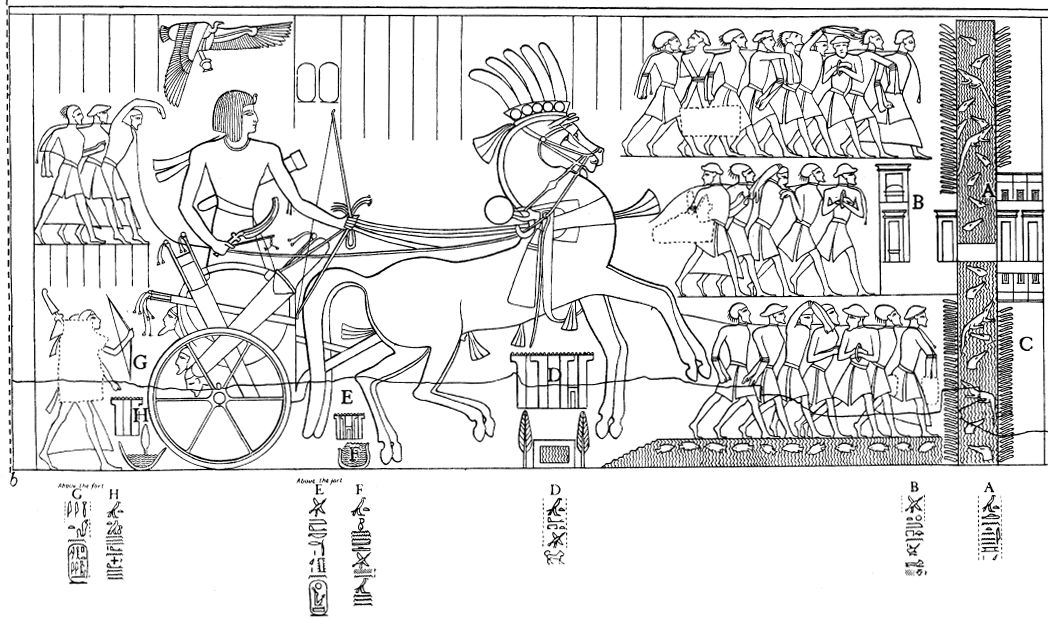

Papyrus Anastasis V (20:2-3) implies that Migdol was built by Pharaoh Seti I of the 19th dynasty,[37] the same king who first established the city of Piramesses. According to a map of the Way of Horus,[38] Migdol (Figure 2, “E”) is east of the Dwelling of the Lion (Figure 2, “D”).

The Dwelling of the Lion has been located at Tell el-Borg,[39] near the north coast of the Sinai Peninsula and the estuary of the Ballah Lakes.[40] The Egyptians reconstructed the site multiple times, as evidenced by its multiple phases including a destruction layer.

A different Migdol, which survived as a fortress into Roman times, was excavated by Eliezer Oren, but this site has no Ramesside period remains. Thus, if this is “the same” Migdol, then the site migrated over time.[41]

Yam Suf, “The Reed (Red) Sea”

The exodus story ends with the splitting of the sea. In many texts, it is simply called the “Sea” but some texts (e.g., Exod 13:18 and 15:22) refer to it as Yam Suf (יַם סוּף). The translation of yam suf as the “Red Sea” is a misleading reading that entered into English Bibles through the Greek Septuagint (ca. 250 BCE) translation Ερυθρὰ θάλασσα.[42]

Hebrew yam suf means “Sea of Reeds,” which most likely comes from the Semitic-Egyptian pȜ ṯwfy, “The Reeds,”[43] one of the lakes (possibly Lake Ballah or Lake Timsah) that were part of the marshy area along what is now the Suez Canal. It is mentioned in P. Anastasi III (2:11-12; quoted above)[44] which states that nearby is the “foliage and greenery” of Pi-Hahiroth (P. Anastasi III, 3:3).[45]

The placement of the three toponyms (Piramesses, Pi-Hahiroth, and Yam Suf) in P. Anastasi III in a geographic sequence similar to what is found in Exodus is highly suggestive to the identity of the biblical sites.

The Toponyms in Exodus and 19th Dynasty Egypt

Most of the textual evidence for the Exodus toponyms dates to the 19th dynasty (1306-1196 BCE). The evidence suggests that most of the occupied areas mentioned in the Exodus account were either founded, renamed during, or hit their peak populations during the reigns of Seti I and Ramesses II, which is congruent with the assumption common among many scholars that the biblical exodus account is set in this period.[46]

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

March 26, 2018

|

Last Updated

February 8, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. David A. Falk is a sessional instructor at the University of British Columbia. He holds a Ph.D. in Egyptology from the University of Liverpool, an M.A. in Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations from the University of Toronto, and an M.Div. and M.A. in Near Eastern and Biblical Archaeology and Languages from Trinity International University. His dissertation is titled, Ritual Processional Furniture: A Material and Religious Phenomenon in Egypt, and among his articles are, “The Egyptian Sojourn and the Exodus” and “Evaluating Chronological Hypotheses in Light of Low, Middle, and High Chronological Frameworks.”

Essays on Related Topics: