Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Part 8

King Abdi-Heba of Jerusalem Commissions a Syrian Scribe

Categories:

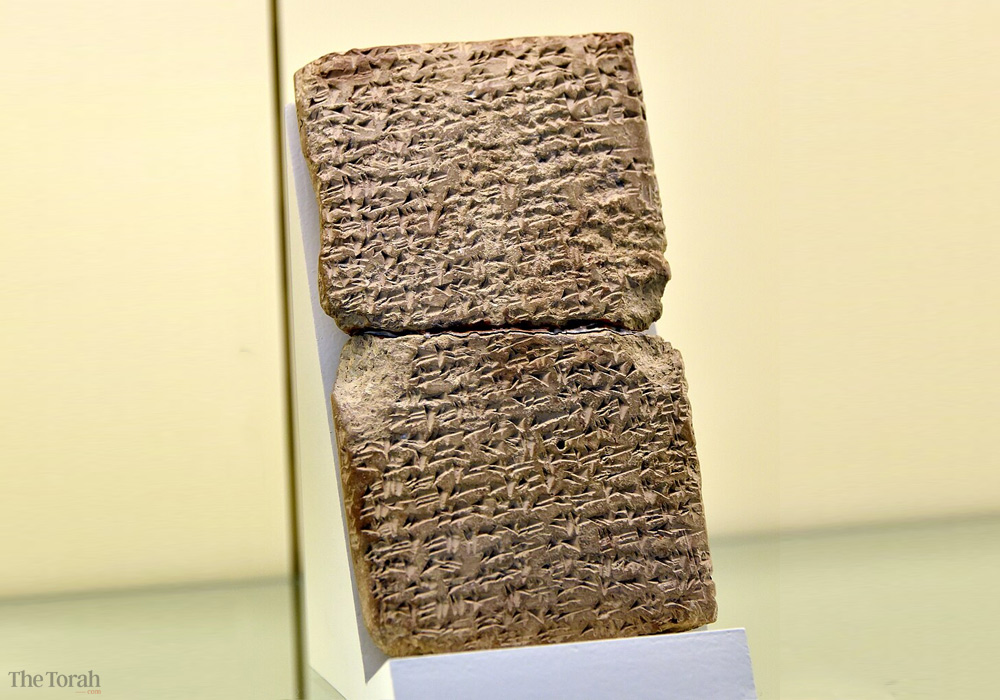

Letter from King Abdi-Heba of Jerusalem to the Egyptian Pharaoh Amenhotep III, Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin (adapted). Wikimedia

The seven Jerusalem-Amarna Letters (EA 285–291) tell us about the local ruler ‘Abdi-Ḫeba, “Servant of Ḫebat,” a Hurrian goddess, and his struggles to keep control of this city.[1] Similarities in the language, orthography, formulae, paleography, and the scribal marks in these letters suggest that they were the work of a single scribe, who was not trained in Canaan.

William Moran, a scholar of the Amarna Letters who was trained by William Foxwell Albright at Johns Hopkins University, and who later taught at Harvard University (from 1966–1990), argued in a 1975 study that this scribe was from the northern Levant. Moran credits his advisor, Albright, with the observation that the scribe’s work was different that that of the other Canaanite Letters. Moran wrote a more comprehensive study, that evaluated the different facets of the letters (their ductus, paleography, orthography, along with their linguistic features). Based on parallels in other cuneiform texts, and certain Assyrian forms, he identified the writer as a “Syrian” scribe.[2] Moran also identified a small number of Canaanite elements in the Jerusalem letters, reflecting the scribe’s enculturation into local, Canaanite scribal practices.

Petrographic analysis, conducted after Moran’s work on this scribe, showed that the clay of letters 286–290 was made from local materials around Jerusalem. Yet two letters were made from different clay sources, which suggests that the scribe was mobile. The clay in EA 285 is from the Egyptian garrison of Beit Shean, and the clay in EA 291 is like the clays around Gezer, a neighboring site.[3] This shows that the Jerusalem scribe traveled locally both in envoys to meet with Egyptian and Canaanite officials. Certain features of the Jerusalem letters also suggest a unique understanding of the terrain, politics, and inner workings of the Egyptian administration.

Handling an Accusation of Disloyalty

As a master scribe and innovator, this scribe used knowledge of Canaanite politics to craft sophisticated letters. For example, in EA 286, after the introduction, the scribe explains that ‘Abdi-Heba has been accused of not being loyal to the pharaoh.

The letter defends ‘Abdi-Heba, acquitting him of wrongdoing, and the scribe’s goal is to dismantle the accusations against him and paint them as ridiculous. Abdi-Ḫeba owes everything to Egypt—his rule in Jerusalem depends on the pharaoh’s support. Instead, the letter continues by casting blame on two other people: Yanhamu an Egyptian official, and Milkilu, the ruler of Gezer,[4] and concludes with a clear message: if the pharaoh wants to maintain power in the region, he needs to send a garrison of troops to Jerusalem.

Because the scribe’s work is so complex, a multimodal perspective is helpful in untangling the different facets of the Jerusalem Letters.[5] Communication theory highlights how writers use different resources—texts are both linguistic and material things. The Jerusalem scribe communicated in the known letters through variation in language, orthography, and through the use of parallelism, and through the use of repetition. For example, in the passage below (from EA 286), the scribe makes use of both standard Akkadian, i.e., a mix of logograms (Sumerian signs that represent Akkadian words, marked in all caps) and syllabic writing, but also Canaanite elements (marked in bold): [6]

5 ma-an-na ep-ša-ti a-na LUGAL EN-ia 6 i-ka-lu ka-ar-ṣi!(MURUB4)-ya : ú-ša-a-ru 7 ⸢i⸣-⸢na⸣ pa-ni LUGAL EN-ri IÌR-ḫé-ba 8 pa-ṭa-ar-mi a-na LUGAL-ri EN-šu 9 a-mur a-na-ku la-a LÚa-bi-ia 10 ù la-a MUNUSú-mi-ia : ša-ak-na-ni 11 i-na aš-ri an-ni-e 12 ⸢zu⸣-ru-uḫ LUGAL-ri KAL.GA 13 ⸢ú⸣-še-ri-ba-an-ni a-na É LÚa-bi-ia [7]

EA 286:5-13 What have I done to the king, my lord? They are slandering me (lit. they are eating my pieces): I am being slandered before the king, my lord: “As for ‘Abdi-Ḫeba, he has deserted the king, his lord.” Look, as for me, neither my father nor my mother put me in this place. Rather, it was the strong arm of the king that caused me to enter to my father's house.”

Only a cuneiform scribe familiar with Akkadian and Canaanite would have been able to read and fully understand this passage. The scribe varies the language and orthographic conventions in this rhetorically important passage. The variation has parallels to how “code-switching” works in spoken language.[8] Speakers use different languages (the classic model for bilingual code-switching), and even dialects of the same language (there is no one “English” but a range of Englishes used globally); and we even use different registers of language, in our own speech practices in the same dialects that we use for communication (for example, I don’t speak in my formal academic lectures the way that I do at home to my hamster). When we write, we also vary our language use.

But, writing has an additional complication: writing is material and visual. We can influence and direct the meaning of a text by playing with the form that language takes. Code-alternation is my own term to describe the fluidity in the variation in the Canaanite Letters, where scribes do more than just vary the language of the text. They use different cuneiform signs, orthographies, scribal marks, harnesses all possible linguistic and extralinguistic aspects of their cuneiform arsenal. We would furthermore assume a degree of intentionally in the process of writing diplomatic letters, that suggest that we should pay attention to where the scribe alternate their writing practices. Context is everything.

In the example of the Jerusalem Amarna Letters, the variation extends beyond language to spelling, scribal marks, grammar, and literary structures. In this case, the nuances of such multimodal layered communication would have been perceptible only to another scribe, but not to someone, such as the pharaoh, just hearing the words of this passage (especially if it was translated in Egyptian, if the letter’s message ever reached pharaoh).

Here, the scribe interwove both more “standard” Akkadian and Canaanite elements into a powerful statement about ‘Abdi-Ḫeba’s loyalty to the pharaoh. Here are some “Canaanite” features of the letters, which are rarer than in the other Canaanite Letters (and therefore when they are used, they seem to stand out). The forms here date to the mid-14th century, are not Hebrew. They are Akkadian words, that use aspects of the local grammar. The scribe was not originally trained in this region. And, these form are used all over the Canaanite Letters (spanning a large region, by speakers, no doubt of many Canaanite dialects).

- The word spelled as ep-ša-ti is an orthographic compound from the Akkadian verb epēšu (“to do”), and a Canaanite 1cs suffix. The uses this Canaanite grammatical ending (the first person common singular suffix [-ti], like in Canaanite dialects (including but not limited to Hebrew). Only a scribe working in Canaan and/or familiar with scribal practices in this reigon would write in this way. The verb was never used this way in Akkadian. The perfective form in Akkadian is patterned on iprus (or iptaras). Suffix forms occur in Akkadian, but in a single construction, the stative. And the 1cs stative Akkadian suffix is -āku (never -ti).

- The scribe uses the Canaanite word “arm” written ⸢zu⸣-ru-uḫ (cognate with later Hebrew זְרוֹעַ) in reference to the pharaoh’s strong arm.

- The scribe uses a well-attested expression Akkadian, to describe how ‘Abdi-Ḫeba is being slandered. The expression literally means, “they are eating my pieces.”[9] However, the scribe follows this expression with ú-ša-a-ru, a Canaanite “gloss,” in the passive form, “I have been slandered.” Here, the scribe even uses a scribal wedge mark, known used here as a gloss mark” to flag this Canaanite form. This same verbal form is seen in another similar passage, written by a scribe writing in the nearby area of Shechem. The scribe writing for Lab’ayu uses a slightly different form of this same middle weak verb: EA 252:13-14 ù i-li qa-bi ka₄-ar-ṣi₂-ia :(scribal mark) ši-ir-ti “And he can speak of my slander: (Canaanite gloss) I was slandered….” The scribe more explicitly marks the verb as a Canaanite form, using the 1cs Canaanite perfective suffix.

- The verb ša-ak-na-ni, “they did not place me,”[10] referring to ‘Abdi-Ḫeba’s parents is an Akkadian verb, yet the verb also has a Canaanite cognate (verbal instantiations of škn). Yet the scribe employs a Canaanite suffix (the 3-person dual), marking this as a non-Akkadian form.

- In this same passage, however, the scribe reverts to a more classic Akkadian form, to describe how the pharaoh has installed ‘Abdi-Ḫeba to his position in Jerusalem. The verb ⸢ú⸣-še-ri-ba-an-ni is an Akkadian form, a 3ms Š-stem of the verb erēbu, which contrasts with the Canaanite elements in this passage.

Context helps us to untangle the scribe’s writing practice. It is telling that the Canaanite forms are in reference to ‘Abdi-Ḫeba and his parents, whereas the scribe uses a more classic Akkadian verb in reference to the pharaoh. The signaling here reflects the identities of these people mentioned, and perhaps a comment of the difference in their relative power and status (local Canaanite elites [=less powerful] vs. the pharaoh [=an international force]).

Then, to beef up the point, the scribe employs parallelism. The two clauses are written in a way that highlights the contrast between the two sets of elites. When read as a multimodal text (the way a scribes would have read it), ‘Abdi-Ḫeba’s message is rich and textured. It openly acknowledges that he did not get his power from his parents (using a Canaanite verbal form), or from the local dynasty. Instead, he acknowledges that his power comes from the pharaoh, who placed him in power (using a more standard Akkadian verbal form).[11]

The parallelism coupled with the scribe’s scribes’ alternation between Canaanite and Akkadian may not have been noticeable to a person hearing an Egyptian translation of this letter. Yet a scribe who was used to reading letters from Canaanite scribes would have noticed the linguistic variation in this passage and its clever organization. In other words, the Jerusalem scribe used these strategies to add texture and depth to the letter, perhaps, with the goal of getting a scribe working for Egypt to communicate the message to the pharaoh [or his officials entrusted with Levantine matters] in a certain way.

The multimodal perspective enables us to evaluate the different communicative elements in the letter, and how they work together as a global rhetorical strategy. We can “read” the subtext of this passage from a scribal perspective: “My parents (local scribal code) did not place me…. But rather, you, of pharaoh, (higher-register of Akkadian), placed me in power….” The scribe contrasts ‘Abdi-Ḫeba’s mother and father with the real source of his power: the mighty arm of his Egyptian overlord.

As noted, the scribe employed a local word to describe the pharaoh’s mighty arm. In another letter (EA 147), another scribe employs the Egyptian term, ḫpš, also in a scribal gloss, to describe the pharaoh’s mighty arm. The use of a Canaanite term in the Jerusalem Letters demonstrates how complex and interesting the letters are, once we read them as scribal artifacts.

Instructions for Other Scribes

Four of the letters from the southern Levant have a secondary message addressed to a scribe. EA 316, and four Jerusalem Amarna Letters. We will look at the examples from our Jerusalem scribe. In four of the letters (EA 286, 287, 288, and 289), the Jerusalem scribe provided instructions on the reverse side as to how the scribes in Egypt should access the main messages on the tablet.[12] While these mini-messages are attached to complicated letters addressed to the Egyptian pharaoh, they are not written for the pharaoh’s eyes but for his scribes, people trained in the cuneiform script who worked for the Egyptian court.

The postscripts in these four letters are all similar. They have a letter heading, and then a all ask the scribe who received the letters in Egypt to present the words of the letter in a favorable way (“present good words to the king, my lord!”). Next, there is a very short message, just a few lines, but all different.

Rather than viewing these messages as separate letters from the main letter, I have argued that they are summaries that the scribe wrote to help the scribes working for Egypt get to the main meat the longer letter on the tablet. The short messages either cite an important word in the main letter on the tablet (EA 286:63-64; 287:66-70; 288:64-66), or summarize the main argument being made (EA 289: 49-51). I’ve called them “CliffsNotes” —short notes from one scribe (our Jerusalem scribe) to the scribes working for the pharaoh.

In other words, they serve as guides to the scribes in Egypt about how to read the letter, and about what information to prioritize; they are scribal cue-cards of a sort. They reach out and communicate: “Dear Scribe who gets this message: please do a good job of communicating it to the pharaoh—and please prioritize this important take-away point.”

Noting a Catch Phrase

The Jerusalem scribe also uses a catch-phrase in bold below from the main letter to tell the scribe where to look for the most important part of the message. For example, in the letter discussed above, the Jerusalem scribe writes a postscript flagging a key phrase repeated many times in the main letter, warning about the loss of the land.

EA 286: 61-64 To the scribe of the king, my lord, thus ʿAbdi-Ḫeba, your servant: Present the eloquent words to the king, my lord! ‘All of the lands of the king, my lord, are lost!’”[13]

This same warning is repeated several times in the main letter, always in important sections of the message, to argue that pharaoh needs to step in and get more involved in governance in Canaan. How can the pharaoh stop the devastation in Canaan? Simple: by sending troops to help ‘Abdi-Ḫeba[14].

In short, scribes wrote letters addressed to the Egyptian pharaoh but at the same time, they were aware that the real audiences of the letters were other scribes—their professional counterparts who received them in Egypt. No one else could read the letters and access their full range of meaning. And the scribes were the gatekeepers for any correspondence in cuneiform addressed to the pharaoh or his officials.

A Glimpse into Pre-Israelite Jerusalem

These examples show us the sophistication of a scribe working in Jerusalem in the Amarna Period. The lucky survival of these documents gives us an unprecedented glimpse into the political world of Jerusalem in a time when it was governed by a Canaanite elite (about whom we do not know much), yet who was very clearly under the thumb of the Egyptian pharaoh. We don’t know whether or not the scribe was actually attached to Abdi-Ḫeba, or, more likely, was appointed there by Egypt and was familiar with Egyptian administration in the Levant.

The Earliest Texts from Jerusalem

The Jerusalem Amarna Letters are the earliest texts from Jerusalem. Yet they were written by an outside scribe, someone who was slowly becoming integrated into the local scribal and political culture. They mention a local elite, someone with a personal name, that connected them to a Hurrian deity. We do not know very much about this person, but their presence in Jerusalem suggests that the site was deemed important to Egypt’s aims of controlling the region.

Other references in the Jerusalem letters suggests that an Egyptian garrison was stationed at Jerusalem for a short period. Above all, the letters show us how interconnected Jerusalem was with Egypt and neighboring sites in the southern Levant, in the 14th century. Earlier Egyptian texts, known as the “Execration texts” offer the first reference to Jerusalem, from an Egyptian perspective. In these texts, Jerusalem is an enemy of Egypt, by the Amarna Period, Jerusalem was integrated into Egypt’s master plan in Canaan.

Even so, we should study the Jerusalem Amarna Letters for their own sake, rather than merely use the letters to study later periods of Jerusalem’s history. When we block out this outside noise, the beauty and mastery of the work of this single scribe crystalizes, and we see the ingenuity and creativity of the first known Jerusalem scribe.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

March 18, 2025

|

Last Updated

September 24, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Alice Mandell is Assistant Professor and William Foxwell Albright Chair in Biblical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies at Johns Hopkins University. She holds a Ph.D. in Hebrew Bible and Northwest Semitics from UCLA’s Department of Near Eastern Languages and Cultures. Her first book, Canaanite Scribal Creativity and the Making of Cuneiform Culture in the Amarna Age, is forthcoming from Routledge.

Essays on Related Topics: