Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Symposium

Levantines in 15th and 14th Century Egyptian Art

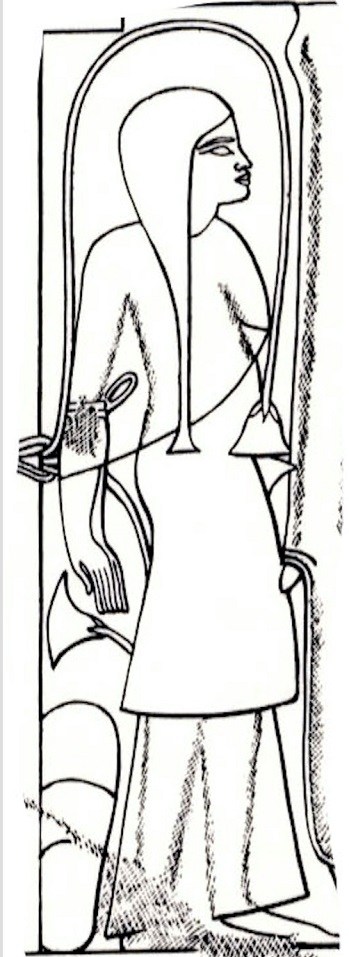

Levantine tribute bearers in the Tomb of Sobekhotep, Thebes, 18th Dynasty © The Trustees of the British Museum

The Egyptian “Us-Against-Them” Imagery

Going back to the very beginning of its history, Egypt used imagery of foreigners as enemies as a political tool. Thus, in the Narmer Palette, from the 31st cent. B.C.E., Narmar, the ostensible founder of Egypt, wearing the White Crown of upper (southern) Egypt, holds a mace in his right hand and the hair of a crouching or fallen enemy,[1] whom he is about to smite, in his left.

Other images displaying the king’s dominion are more stylized, such as the statue of Thutmose III as a sphinx reclining on the nine bows, which represent Egypt’s traditional enemies.[2]

Such imagery expresses the pharaoh’s responsibility to keep Egypt’s enemies at bay but had significance beyond highlighting his power.[3] Egyptians parsed the world as a struggle between order (maat) and chaos (isfet), and a key part of the pharaoh’s job was to maintain maat.[4] This expressed itself both in ritual acts as well as in protecting civilized, ordered Egypt from the encroachment of foreigners, who represent the forces of chaos:

Re has placed King N

in the land of the living

for eternity and all time;

for judging men, for making the gods content,

for creating order, for destroying chaos.[5]

Levantine Enemies

One of Egypt’s traditional enemies that appear in many Egyptian smiting scenes are the Levantines. Levantines is an umbrella term for people from the lands north of Egypt, stretching from the Sinai through ancient Canaan, Lebanon, Syria, the Transjordan and up to Anatolia. The Egyptians were well aware of the fact that many distinct peoples lived in this area and label these northern foreigners Tunip, Hatti, Retenu, Mittani, Kadesh, Mennu, or Apiru.

Nevertheless, no matter what label was used in the depiction of any given Levantine, the Egyptian artists portrayed them in the same manner, with the same attire. This is likely because the Egyptians were more focused on conveying specific messages to the intended ancient Egyptian viewer than in creating an encyclopedic compendium of how contemporary foreigners looked. Even so, these paintings are surely rooted in historical reality.

In this piece, we will focus on the image of Levantines in the 18th dynasty, specifically, during the reigns of Thutmose III–Tutankhamun (ca. 1504–1325 B.C.E.), which corresponds more or less to the period of Israelite bondage in Egypt, according to the biblical chronology.[6]

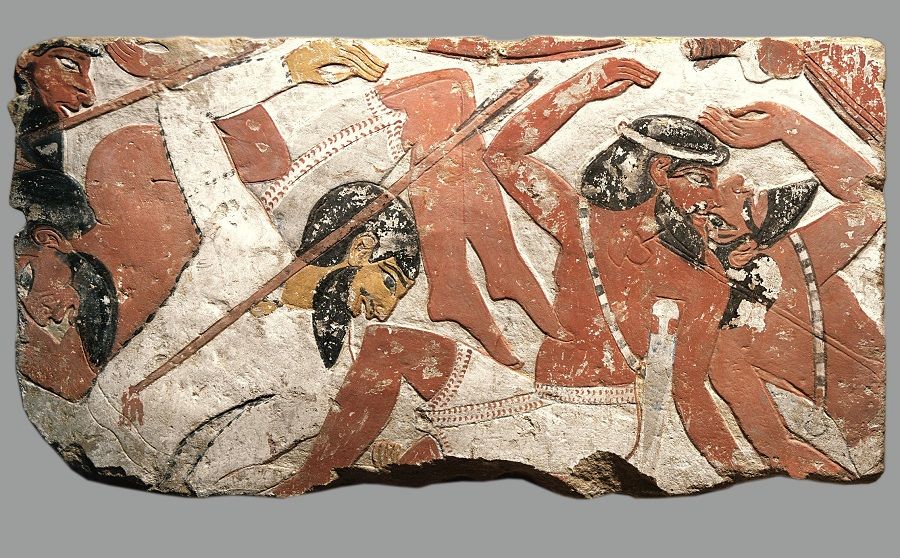

Levantine Bodies on the Battlefield

A battle scene originally adorning the exterior of a temple wall depicts northern foreigners being trampled by the king riding his chariot.[7] Much of the relief has been lost, but what survives shows, from a birds-eye view, the bodies of Levantines shot down by the Egyptian king’s arrows scattered haphazardly on the battlefield.[8] The Levantine soldiers carry daggers and wear quiver straps around their chests as they were when going into battle.

This wall fragment is datable because the Levantines are depicted as wearing a pointed skirt or an ankle length, long sleeved white gown, sometimes called the “long Syrian robe,” or a galabeya. This garment was edged in red and/or blue, with little other decoration. This attire is familiar only from art in the reigns of Thutmose III- Amenhotep II (1479–1400 B.C.E.).

While Egyptians are clean shaven, northern foreigners are depicted with full beards, and their hair is either closely cropped or shoulder length, held in place with a fillet (a band or ribbon wrapped around the head). Unlike Egyptian men depicted with red skin, Levantines are sometimes rendered with yellow skin, a color otherwise reserved for Egyptian women.

Bound Foreigners in Theban Tomb Paintings

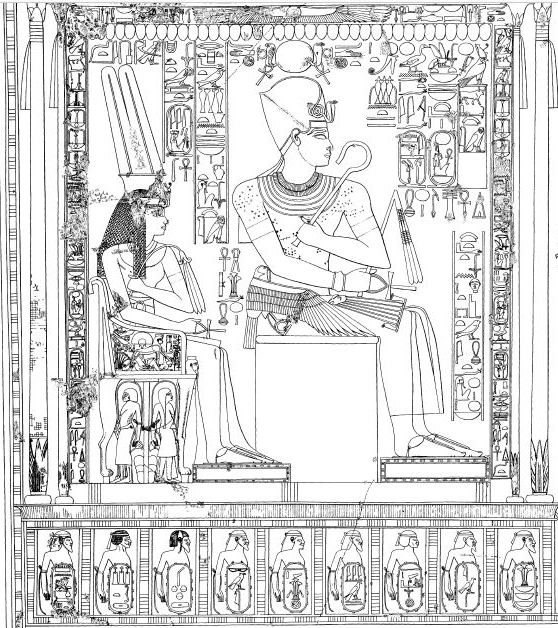

Related to the battle scene imagery is the “bound and trampled” foreigner motif, generally found on thrones, royal footstools or kiosks. In this motif, a combination of a northern foreigner (Levantine) and a southern foreigner (Nubian) are depicted in a way that renders them physically restrained and crushed. Such imagery portrayed the pharaoh’s almighty dominion, from north (Levant) to south (Nubia).

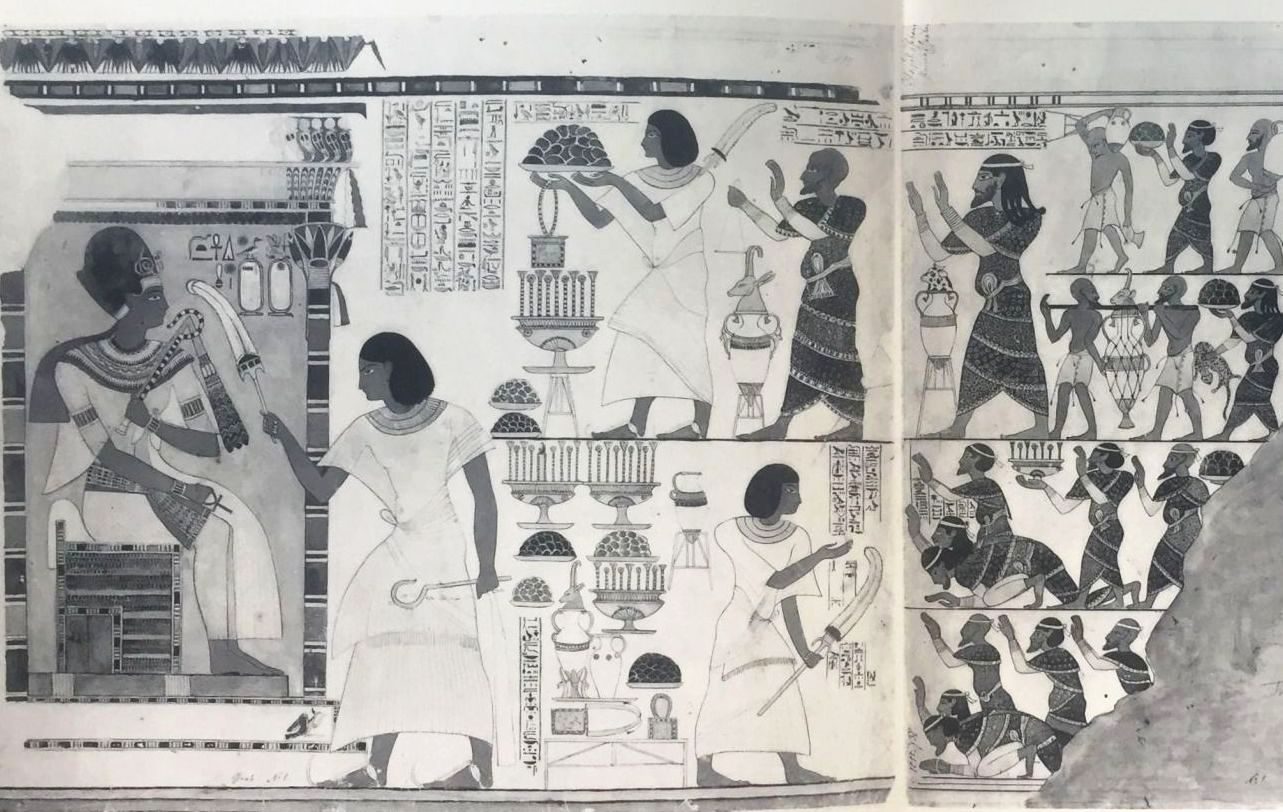

Such imagery was also used in the Theban tomb paintings of officials, depicting images of their pharaoh enthroned in the palace. For instance, the kiosk from the tomb of Anen (the Second Prophet of Amun during the reign of Amenhotep III), shows foreigners in their most ornate and expensive attire, indicating that the pharaoh is crushing the leaders of these foreign people.

As above, the Levantine men in these images have beards and long hair worn with a fillet, either chin length or shoulder length, ending in curls or a shaved head. In this image, the attire is not plain white, but colorful elaborate attire consisting of a full galabeya and a cape that wraps around the shoulders, and another colorful piece of fabric wrapped several times around the skirt, much like a sari.[9]

This image is the best remaining picture we have to show the variety of colors and decorations on the clothes of ancient Levantine rulers, conspicuous consumption likely explains the layers of elaborate clothing.

Levantines Paying Tribute: A Cosmopolitan View

In the 18th dynasty, a new context for depicting foreigners appears in Egyptian art: tribute scenes,[10] in which foreign delegations bring offering gifts to the Pharaoh. These scenes appear in the tombs of high ranking officials which were located in Thebes. As the American archaeologist James B. Pritchard (1909–1997) notes,

The paintings upon the walls of the New Kingdom tombs at Thebes constitute the principal source for our knowledge of the appearance of the inhabitants of Palestine, Syria, and the upper Euphrates during the second half of the second millennium B.C.[11]

Tombs with these images show a new, cosmopolitan view of foreigners that was the result of Egyptian elites participating in an international culture with elites from around the Mediterranean coast during the Late Bronze Age.[12] This sudden change in the way foreigners are depicted by the Egyptians goes hand in hand with a new international interest with prestige obtained in part through foreign, exotic luxury goods. In fact, such goods are one of the primary foci to the ancient viewer.

Men of Rank

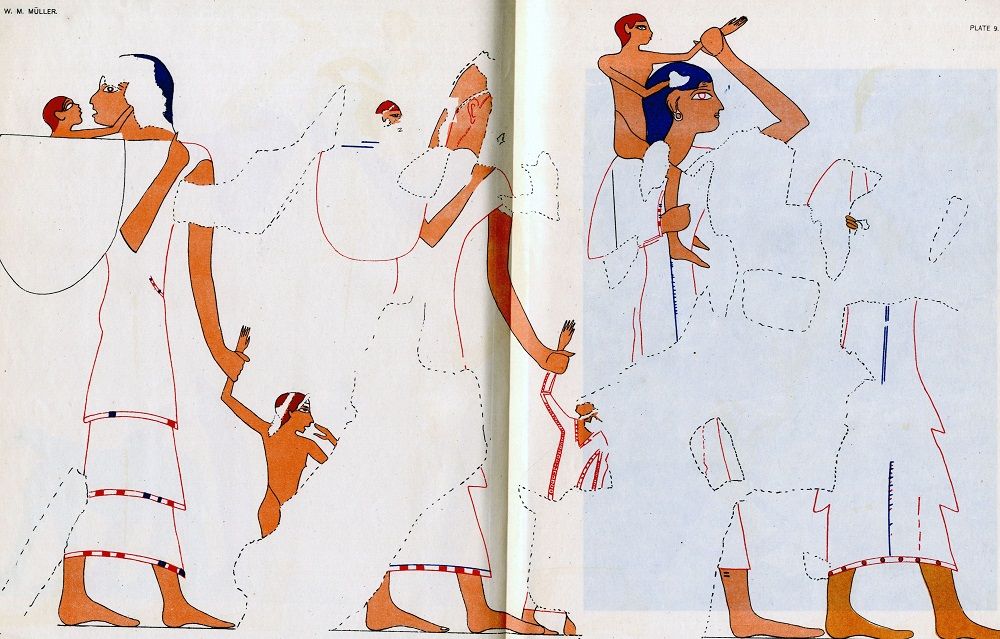

In tribute bearer images, the chiefs kneel in the front of the procession and are rendered on a larger scale than the following male tribute bearers. In an image from the tomb of Sobekhotep (see top image), treasurer of the Pharaoh, the figures wear a galabeya with a long thin piece of fabric wrapped around the skirt. The chiefs are again depicted with a cape shawl, indicating their higher status.

Status is also a key clothing marker in later images, best exemplified by paintings from the tomb of Huy (TT 40), viceroy of Nubia.[13]

Levantine figures here wear a new style of ornately decorated dress over a white undergarment, with layers of folds forming patterns around the skirt, girded with a belt decorated with dots and a rectilinear motif at the edges. The less high-ranking males in these same tomb images wore simple white kilts that come to the point in the center that had tassels hanging below the skirt at both the waist as well as the center and sides of the its bottom hem.

Men wear their hair in a variety of fashions that do not seem indicative of rank: shoulder length and curled at the bottom, chin length, or shaved. Unlike earlier images of Levantines, men with hair and without hair can don the fillet, and all men regardless of hairstyle or rank wear a beard.

Male Captives

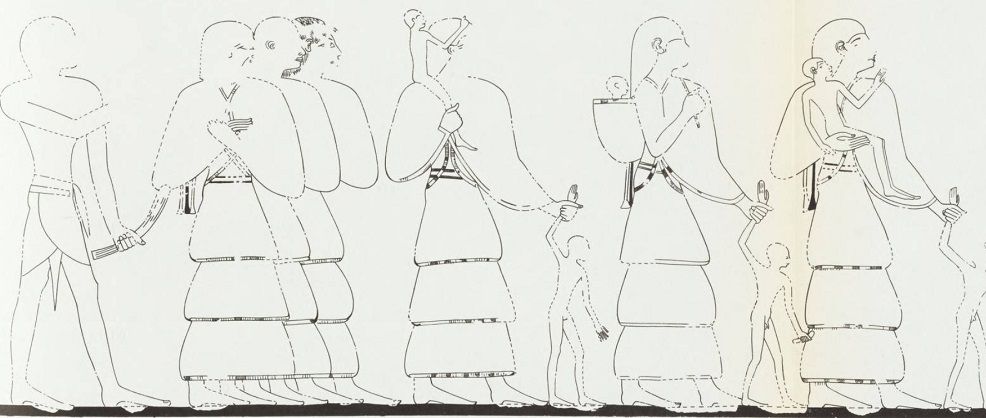

In the tomb of Rekhmire, a governor of Thebes and vizier to Thutmose III and Amunhotep II, we find an image of fourteen Levantine captives in two groups.

The first group has cropped hair and wears a cape shawl over a galabeya. The second group wears their hair a bit longer and wears a cape shawl with a skirt that comes to a point between the legs.

When viewed in color it is easy to see what else sets these figures apart: some of them have red hair (Fig. 8), which in Egypt, would have been considered unattractive. The images of red heads within these tomb paintings are drawn with unkempt hair and wrinkles on their faces, which contrasts to the Levantines who do not have red hair.[14]

The word for color in Egyptian, “iwen” also translates as “character” or “disposition.” Red was a color associated with the god Seth, and the idea of chaos. This color was so powerful that when drawing the god Seth, Egyptian scribes would change ink color, from black to red, just to depict this god in the color of chaos.

Red hair was also associated with foreigners from the Levant. This may stand behind the Bible’s description of both Esau—the founding father of the Edomites—and King David as read-headed (Gen 25:25, 1 Sam 16:12).[15]

Female Captives

Captive Levantine women and children follow the men in the tribute images from the Theban tombs.[16] The women from the tomb of Rekhmire are shown with a short-sleeved long dress that have three tiers in the skirt. Levantine women are typically represented with long hair that falls behind their back. In images where the hair falls in front of their shoulder, it is shown gathered together, as if tied near the bottom.

When carrying a basket or satchel of children on their back, the women hold the rope at their shoulders to relieve the weight. This contrasts with the Nubian women who wear the basket or satchel strap on their forehead to lighten the load. None of the foreigners wear head-coverings or veils.

In Rekhmire’s tomb, Levantine women are depicted with slender physiques, and their breasts are not indicated in the tribute scene images, which contrasts with how the Egyptian women are represented. The ideal Egyptian woman’s figure is slender with full breasts, as can be seen in the figure of Queen Tiye, wife of Amenhotep III.

Underneath the image of the ideal Egyptian woman, as embodied by the queen, is the only example of the bound and trampled foreigner motif that depicts women. Here, in only this instance, the Levantine women have pendulous breasts and a slightly protruding belly.

In Egyptian imagery, this body type, reflects women post childbirth and nursing.

As with the petite body type, this image also did not meet Egyptian standards of beauty, and was usually reserved to render Nubian women[17] who are shown in tribute scenes carrying up to four children with them, more than the petite Levantines carry in the same scenes.

In short, thin women with no indication of breasts and larger women with pendulous breasts both contrast with the ideal female image of a woman in the prime of her youth, who has a slender figure with full breasts, in the physical prime of her childbearing years.

The Egyptians are depicting a set of ideals on these tomb walls. In contrast to these “unattractive” Levantine and Nubian captives, all Egyptian women, no matter their age, are depicted in an ideal fashion with the Egyptian version of the ideal body. This is likely a convention associated with the function of the tomb, a vehicle of rebirth into the next life.

Children

The children captives shown in the tribute images are shown either in panniers on women’s backs or are being held by their wrists. The Egyptian convention of depicting children without clothing, with their hair in a side lock, and their hand to their mouth was used to depict foreign children as well. Levantine children could also be depicted as small adults, following the conventions of either a man or woman.

Foreigners in Egypt

Living in Egypt as a foreigner was challenging, and individuals tended to assimilate into Egyptian society, in order to try and shake the stigma of being non-Egyptian. This can be seen most clearly in how Pharaoh’s of foreign origin, such as the dynasties of the Hyksos (14th and 15th), Libyans (24th), Kushites (25th), and the Greeks (Ptolemaic, the last being the famous Queen Cleopatra VII) presented themselves as Egyptian in official documents and art.

Foreigners were a part of almost every level of Egyptian society throughout its history,[18] and many reached its upper echelons. Moreover, sons of royal rulers from foreign kingdoms even grew up with the pharaoh in the royal Egyptian nursery.[19]

We do not know how successfully these foreigners became Egyptianized in reality, especially in the lower classes, about whom we know very little. Nevertheless, we do have some images of foreign Levantine workers in Egypt during this period.

The Workers in Rekhmire’s Tomb Painting: Israelite Slaves?

Returning to the tomb of Rekhmire, we find one rather inconspicuous image of workers making mudbricks, the very work that the Hebrew slaves performed according to Exod 1:14.

שמות א:יד וַיְמָרְרוּ אֶת חַיֵּיהֶם בַּעֲבֹדָה קָשָׁהבְּחֹמֶר וּבִלְבֵנִים וּבְכָל עֲבֹדָה בַּשָּׂדֶה אֵת כָּל עֲבֹדָתָם אֲשֶׁר עָבְדוּ בָהֶם בְּפָרֶךְ.

Exod 1:14 They made their lives bitter with hard service in mortar and bricks and in every kind of field labor. They were ruthless in all the tasks that they imposed on them.

Moreover, Exodus 5 focuses on a back and forth between Pharaoh and the Israelites about their failure to produce their quota of bricks (after Pharaoh tells the taskmasters to stop supplying them with straw, to make the work harder).[20]

If we look at the imagery of people making bricks in Rekhmire’s tomb, their dress is of simple loincloths like those of Egyptian peasants. Yet, the accompanying text specifically identifies them as captives brought by his majesty to make bricks for the temple of Amun at Karnak in Thebes.

Moreover, their physical traits and appearance are not Egyptian, they are Nubians and Levantines. The men have various Levantine traits, one has blue eyes, two have light colored body hair and all three have light skin and hair. None of these physical traits would be used to depict Egyptian men. Another wall within the same tomb depicts Levantines at work, wearing plain white kilts, also an Egyptian style. We do not know specifically where these Levantines are from, perhaps Retenu (Canaan).

The images in Rekhmire’s tomb show Egyptians making use of foreign Levantine slaves for mudbrick building projects. We even have pictures of what they looked like doing it, from an ancient Egyptian perspective. For those who assume a historical core for the claim of Israelite slavery or hard labor in Egypt during this period, this would be the best evidence we have for what they would have looked like, at least, in the eyes of their Egyptian masters.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

April 18, 2019

|

Last Updated

December 27, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Flora Brooke Anthony is an Egyptologist and Subject Matter Expert featured on the History Channel and the Discovery Channel. She earned her Ph.D. in Art History from Emory University and holds a master’s from the Institute of Egyptian Art and Archaeology at the University of Memphis. Flora is the author of Foreigners in Ancient Egypt: Theban Tomb Paintings from the Early Eighteenth Dynasty (2016). She currently serves as Director of Grants at the Academic Torah Institute - TheTorah.com.

Essays on Related Topics: